Office Application History: Part II

Our previous text ended with a total Microsoft Office victory in the 90s: most users, in principle, did not think to use anything else. It was difficult to compete, if only because its standards became generally accepted, people needed to work with them, and there were concerns "in another editor, the documents sent to me would go all the layout." Can other companies, in principle, oppose such domination? As shown by the XXI century, they can.

')

In 1999, a giant company, Sun Microsystems, bought a small StarDivision, which developed the StarOffice office suite. Why, if Microsoft at that moment seemed to be the only alternative? And why did the company, which was primarily engaged in the sale of servers, suddenly climbed into office software?

The fact is that the goal of "discouraging the entire market from Microsoft" was not pursued. According to Simon Phipps, who occupied an important post at Sun at that time, the main reason for the purchase was as follows: the company employed 42,000 people, so it was simply decided that it would be better to get your own office suite than to pay Microsoft for a huge number of Office licenses. This is the scope.

Even if his words were an exaggeration, and the external goals for Sun were important too, they were not about earning as much as possible through the usual commercial sale of the package. StarOffice had versions for Linux and Solaris, and the company's activities were related to both of these operating systems, and she was interested in widely distributing a good office suite for them — and that was profitable to her strategically without profit.

Therefore, the company approached the distribution of its product is not like Microsoft. Continuing to develop new versions of StarOffice, in 2000 she created the project OpenOffice.org , within the framework of which she made the source code StarOffice available. Now anyone could at least use the package for free, even though (with programming skills) add his code, creating a more suitable version for himself.

This was a breakthrough for Linux, where compatibility with Microsoft Office formats was always a sore point, and access to source code was appreciated. Although the share of Linux among operating systems was low, in his case there was no competition at all from Microsoft Office, so popularity among its users was ensured. In the Windows world, the package did not think so, but it also found its followers - among those who share the open source ideology, and among those who simply want to save money. The result was a niche product that does not claim leadership, but within its niche is more than sought-after.

However, the initial delighted sighs of many were replaced by disappointment. The Sun slowly developed the project, although its active users voiced a lot of considerations "this is a clear problem with this, it just needs to be fixed." Moreover, among these active users were developers who were able to cope with the task on their own. One of the advantages of open source is the ability of enthusiasts to help their favorite project by adding something for it, and it may seem that it saves the situation: if Sun doesn’t have time, they can use someone else’s work. However, a large company with strict rules was not ready to easily take someone else's code and use it in a project, and the process was delayed again.

It turned out that the most ardent supporters of the project began to experience very negative emotions: they saw a problem in their favorite software, wanted to fix it, were ready to do the work for this, and the software owner refused to accept this work, at the same time not doing it . It is not surprising that criticism was heard against Sun, primarily from developer Michael Mix. The company was accused of bureaucracy reigning there, because of the reluctance to take someone else’s code, the same work was done twice, and any change was terribly long tested, although those holes that need to be urgently plugged are larger than the small errors that can cause lack of testing. As a result, under the guidance of Mix , a set of patches from third-party developers ooo-build was created , which partially complemented OpenOffice.org, without waiting for Sun to implement the same features. And later, in 2006, under the leadership of Novell, this set expanded to a separate Go-oo package, based on the OpenOffice.org code and readily adding someone else's code.

Sun reacted negatively: for example, Simon Phipps called the project "hostile rival fork" and said that Novell fed developers a tale of "resisting the evil Sun and the forces of good," while pursuing their own interests. There was a situation where all the parties involved want the project the best, but they almost fight, and users are faced with a choice of two options.

Gradually, active users flowed from OpenOffice.org to Go-oo, and in 2010 there was a sharp shake-up. Oracle bought Sun Microsystems, and many were worried about what it would do with open source projects that came into its hands. Oracle's subsequent lawsuit against Google regarding the use of Java in Android has heightened fears as an unfriendly move towards free source code. Since Oracle has also reduced the number of employees employed by OpenOffice.org, many third-party developers have felt that the project must be saved.

With the help of the new organization The Document Foundation , the LibreOffice fork was created , which incorporated the work of Go-oo. It was actively developed, quickly became the favorite of the open source community (many Linux distributions immediately include it in their membership), and now, when it comes to open source office software, they first of all remember it, and not development which he originally budded off.

In parallel, another niche story unfolded. If in the 90s Apple lost almost everything, then after the appearance of the iMac in 1998 and the iPod in 2001, the company again declared itself. Yes, for Mac all this time there was a version of Microsoft Office (moreover, some features still appeared there earlier than in the version for Windows). However, it is known that Apple advocates a unified approach to hardware and software, and many owners of gadgets of the company share this ideology - it is not surprising that there was a demand for development directly from Apple, which allows the user not to encounter Microsoft interfaces. And in 2005, the iWorks replaced the outdated AppleWorks.

In some respects, it was inferior to Microsoft Office, partly intentionally: the company did not even try to cover the needs of 100% of users. As in many other cases, Apple chose not to put on the most complete set of functions, but on the simplest and most understandable interface for most people. And it turned out that it works: of course, the market share was strictly limited to the number of Macs in the world, but the “makovods” fell in love with the package, arguing in some cases that it was impossible to look at Office after it without tears. So there was another situation where Microsoft pinched the market share slightly, but surely, having acquired very loyal users.

But the main thing that happened in the middle of the zero remained less noticed due to the fact that its scale was not immediately apparent. In web development, the Ajax principle became widespread, implying that web pages should be able not only to be completely updated (annoying the user by waiting), but also dynamically changing their content depending on their actions without any reload - for example, Google introduced auto-completion of the request, and for those times it was amazing to see instantly crawling tips to the text just entered.

In 2005, the Upstartle startup was inspired by this principle, having decided to check what this approach would give to text editing - and made Writely web service. And in 2006, Google bought Upstartle, and Writely's practices migrated to the new Google Docs service. A similar story occurred with the spreadsheet Google Spreadsheets, also introduced in 2006: it also began as a separate product, XL2Web, from a startup 2Web Technologies.

At that moment it was easy not to notice that a revolution had occurred. Internet access for many users left much to be desired. YouTube and social networks have not yet enjoyed today's popularity, so people are not used to the fact that you can do almost anything in the browser. In addition to this, the web service also drastically limited the user’s capabilities compared to the usual desktop office. In general, the first time Google Docs existed, the flaws were obvious, and the advantages were not quite.

But later it turned out that a time bomb was laid under the office software market, which subsequently changed the very approach to this software. As Google Docs evolved, the Internet accelerated, and the world increasingly used cloud products, the flaws gradually became less significant. And then the advantages were noticeable: from the fact that access to the document can be obtained at any time (without “forgot the flash drive” or “left on the working computer”), to collaborative work that allows people to simultaneously make changes to the document, observing in real time each other.

And besides, "cloudiness" contributed another major factor - but about it in the next chapter.

')

Open source

In 1999, a giant company, Sun Microsystems, bought a small StarDivision, which developed the StarOffice office suite. Why, if Microsoft at that moment seemed to be the only alternative? And why did the company, which was primarily engaged in the sale of servers, suddenly climbed into office software?

The fact is that the goal of "discouraging the entire market from Microsoft" was not pursued. According to Simon Phipps, who occupied an important post at Sun at that time, the main reason for the purchase was as follows: the company employed 42,000 people, so it was simply decided that it would be better to get your own office suite than to pay Microsoft for a huge number of Office licenses. This is the scope.

Even if his words were an exaggeration, and the external goals for Sun were important too, they were not about earning as much as possible through the usual commercial sale of the package. StarOffice had versions for Linux and Solaris, and the company's activities were related to both of these operating systems, and she was interested in widely distributing a good office suite for them — and that was profitable to her strategically without profit.

Therefore, the company approached the distribution of its product is not like Microsoft. Continuing to develop new versions of StarOffice, in 2000 she created the project OpenOffice.org , within the framework of which she made the source code StarOffice available. Now anyone could at least use the package for free, even though (with programming skills) add his code, creating a more suitable version for himself.

This was a breakthrough for Linux, where compatibility with Microsoft Office formats was always a sore point, and access to source code was appreciated. Although the share of Linux among operating systems was low, in his case there was no competition at all from Microsoft Office, so popularity among its users was ensured. In the Windows world, the package did not think so, but it also found its followers - among those who share the open source ideology, and among those who simply want to save money. The result was a niche product that does not claim leadership, but within its niche is more than sought-after.

However, the initial delighted sighs of many were replaced by disappointment. The Sun slowly developed the project, although its active users voiced a lot of considerations "this is a clear problem with this, it just needs to be fixed." Moreover, among these active users were developers who were able to cope with the task on their own. One of the advantages of open source is the ability of enthusiasts to help their favorite project by adding something for it, and it may seem that it saves the situation: if Sun doesn’t have time, they can use someone else’s work. However, a large company with strict rules was not ready to easily take someone else's code and use it in a project, and the process was delayed again.

It turned out that the most ardent supporters of the project began to experience very negative emotions: they saw a problem in their favorite software, wanted to fix it, were ready to do the work for this, and the software owner refused to accept this work, at the same time not doing it . It is not surprising that criticism was heard against Sun, primarily from developer Michael Mix. The company was accused of bureaucracy reigning there, because of the reluctance to take someone else’s code, the same work was done twice, and any change was terribly long tested, although those holes that need to be urgently plugged are larger than the small errors that can cause lack of testing. As a result, under the guidance of Mix , a set of patches from third-party developers ooo-build was created , which partially complemented OpenOffice.org, without waiting for Sun to implement the same features. And later, in 2006, under the leadership of Novell, this set expanded to a separate Go-oo package, based on the OpenOffice.org code and readily adding someone else's code.

Sun reacted negatively: for example, Simon Phipps called the project "hostile rival fork" and said that Novell fed developers a tale of "resisting the evil Sun and the forces of good," while pursuing their own interests. There was a situation where all the parties involved want the project the best, but they almost fight, and users are faced with a choice of two options.

Gradually, active users flowed from OpenOffice.org to Go-oo, and in 2010 there was a sharp shake-up. Oracle bought Sun Microsystems, and many were worried about what it would do with open source projects that came into its hands. Oracle's subsequent lawsuit against Google regarding the use of Java in Android has heightened fears as an unfriendly move towards free source code. Since Oracle has also reduced the number of employees employed by OpenOffice.org, many third-party developers have felt that the project must be saved.

With the help of the new organization The Document Foundation , the LibreOffice fork was created , which incorporated the work of Go-oo. It was actively developed, quickly became the favorite of the open source community (many Linux distributions immediately include it in their membership), and now, when it comes to open source office software, they first of all remember it, and not development which he originally budded off.

Closed source code

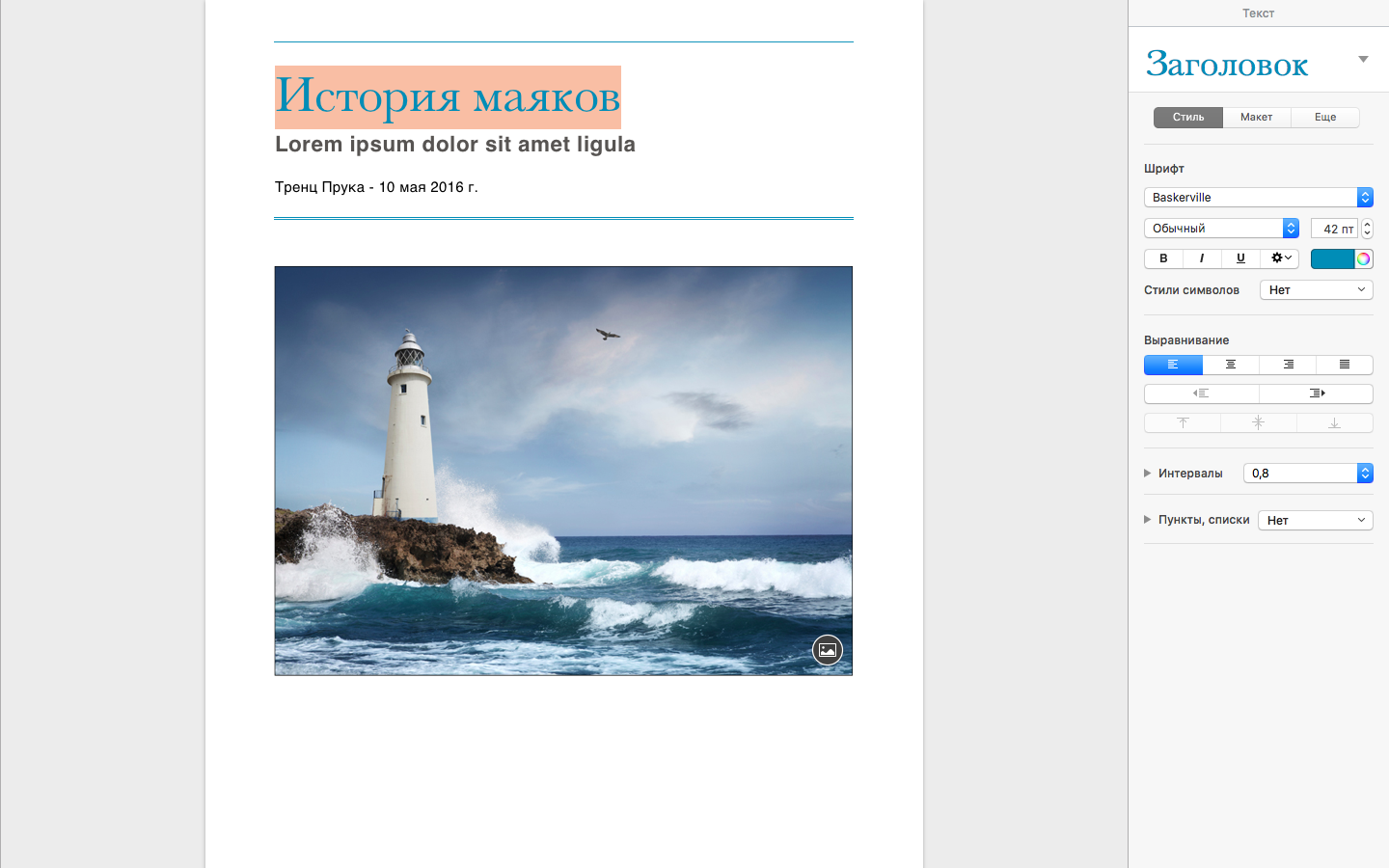

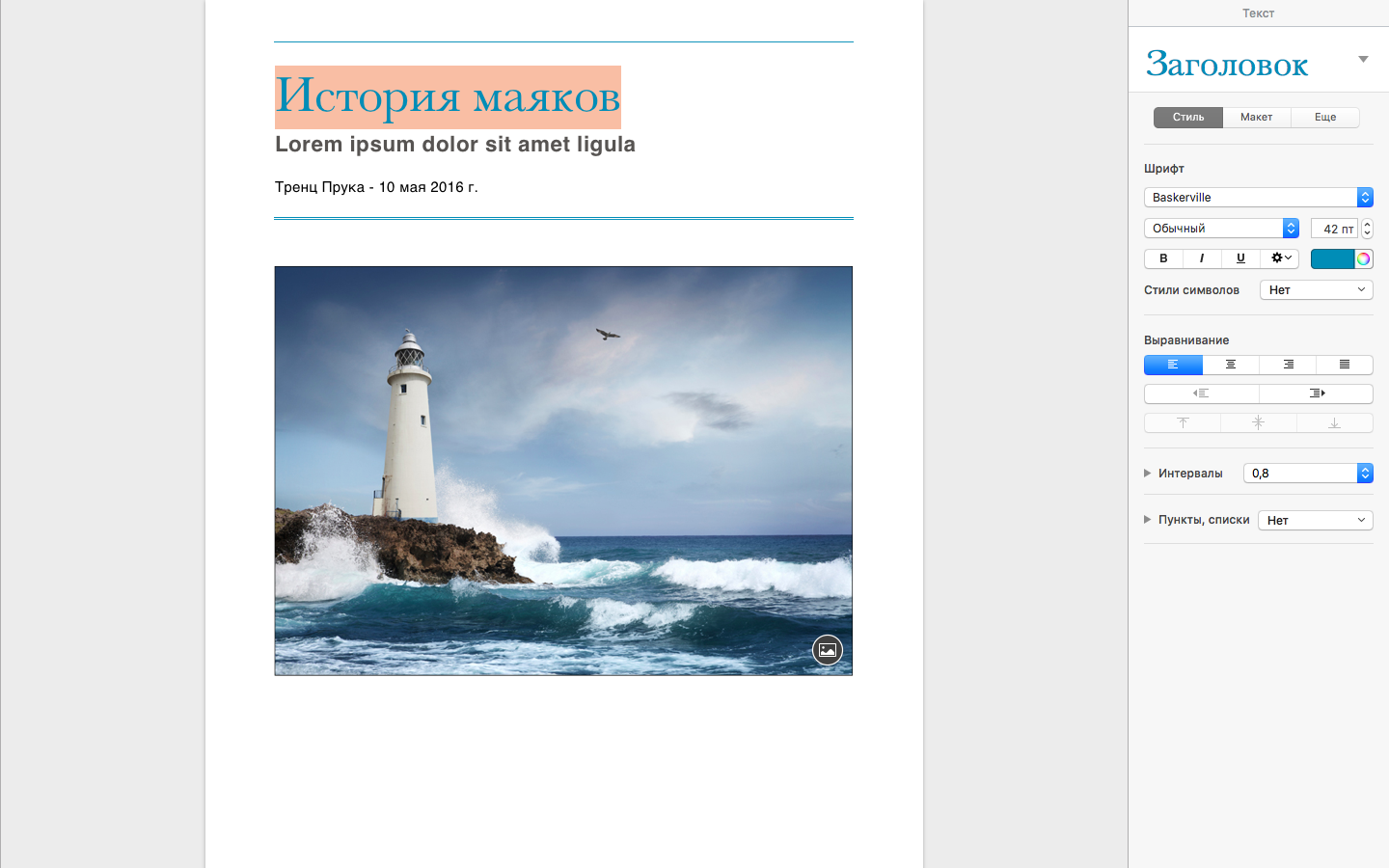

In parallel, another niche story unfolded. If in the 90s Apple lost almost everything, then after the appearance of the iMac in 1998 and the iPod in 2001, the company again declared itself. Yes, for Mac all this time there was a version of Microsoft Office (moreover, some features still appeared there earlier than in the version for Windows). However, it is known that Apple advocates a unified approach to hardware and software, and many owners of gadgets of the company share this ideology - it is not surprising that there was a demand for development directly from Apple, which allows the user not to encounter Microsoft interfaces. And in 2005, the iWorks replaced the outdated AppleWorks.

In some respects, it was inferior to Microsoft Office, partly intentionally: the company did not even try to cover the needs of 100% of users. As in many other cases, Apple chose not to put on the most complete set of functions, but on the simplest and most understandable interface for most people. And it turned out that it works: of course, the market share was strictly limited to the number of Macs in the world, but the “makovods” fell in love with the package, arguing in some cases that it was impossible to look at Office after it without tears. So there was another situation where Microsoft pinched the market share slightly, but surely, having acquired very loyal users.

But the main thing that happened in the middle of the zero remained less noticed due to the fact that its scale was not immediately apparent. In web development, the Ajax principle became widespread, implying that web pages should be able not only to be completely updated (annoying the user by waiting), but also dynamically changing their content depending on their actions without any reload - for example, Google introduced auto-completion of the request, and for those times it was amazing to see instantly crawling tips to the text just entered.

In 2005, the Upstartle startup was inspired by this principle, having decided to check what this approach would give to text editing - and made Writely web service. And in 2006, Google bought Upstartle, and Writely's practices migrated to the new Google Docs service. A similar story occurred with the spreadsheet Google Spreadsheets, also introduced in 2006: it also began as a separate product, XL2Web, from a startup 2Web Technologies.

At that moment it was easy not to notice that a revolution had occurred. Internet access for many users left much to be desired. YouTube and social networks have not yet enjoyed today's popularity, so people are not used to the fact that you can do almost anything in the browser. In addition to this, the web service also drastically limited the user’s capabilities compared to the usual desktop office. In general, the first time Google Docs existed, the flaws were obvious, and the advantages were not quite.

But later it turned out that a time bomb was laid under the office software market, which subsequently changed the very approach to this software. As Google Docs evolved, the Internet accelerated, and the world increasingly used cloud products, the flaws gradually became less significant. And then the advantages were noticeable: from the fact that access to the document can be obtained at any time (without “forgot the flash drive” or “left on the working computer”), to collaborative work that allows people to simultaneously make changes to the document, observing in real time each other.

And besides, "cloudiness" contributed another major factor - but about it in the next chapter.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/394053/

All Articles