Javascript without loops

Once I wrote that indentation can be considered an indicator of the complexity of the code (albeit rather coarse). The indents themselves are neutral, since they are only a means of text formatting, but the whole point is that they are used to select specific program blocks, for example, control structures. While reading the code and bumping into the indent, the programmer has to take into account what the indent indicates, to keep in mind the context in which the allocated block exists. This, of course, is repeated if another special fragment appears in the indented portion of the code.

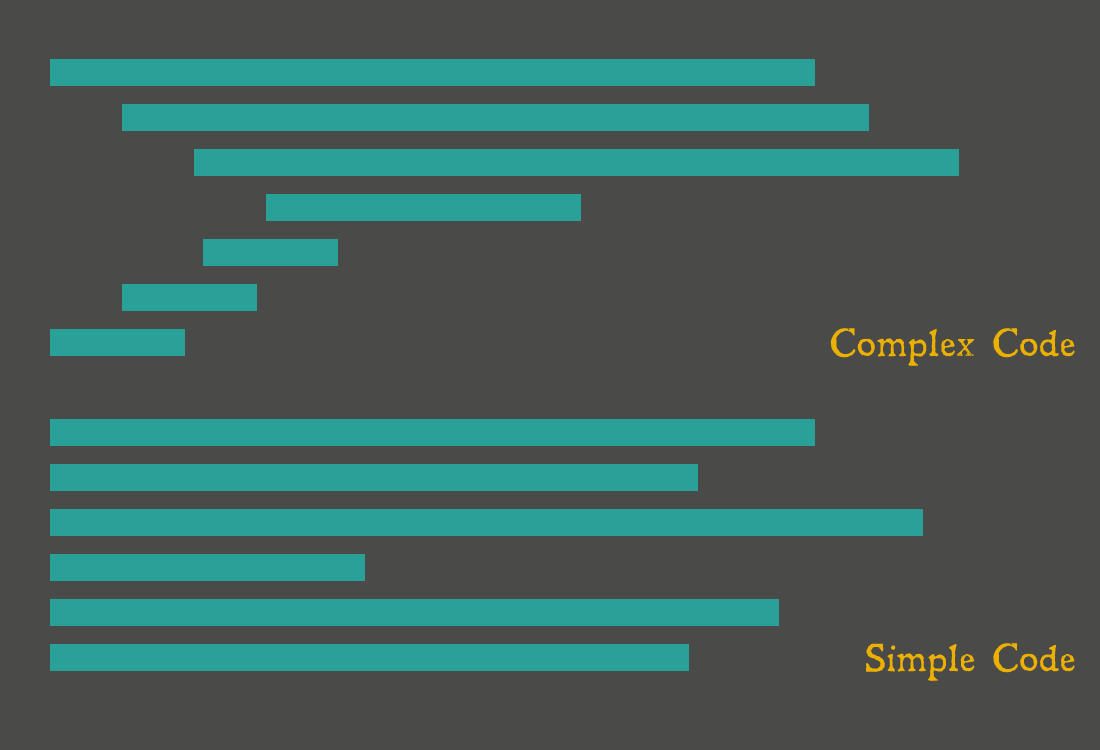

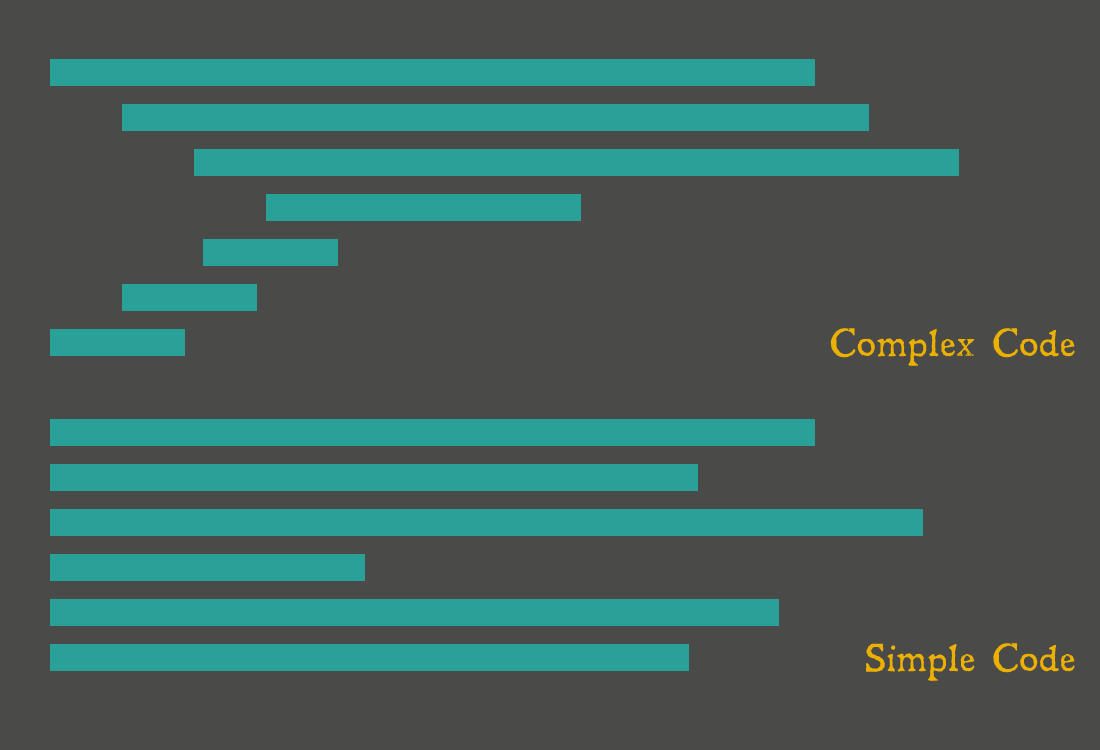

If you don’t pay attention to the content of the texts, here’s how a complex code usually looks, the sections of which look like the letters “V” lying on its side, and a simple code whose block, if not taking into account the different lengths of lines, looks like a rectangle.

The more indents, the more difficult the code is.

Constructions that need to be indented will always be in the code, there is no question of completely getting rid of them. However, we are able to reduce the complexity of the programs that we write, due to the rational choice of abstractions for solving the problems we face.

')

Take, for example, arrays. Traditionally for their processing use various types of cycles. The concepts of "array" and "cycle" are inextricably linked in the minds of many programmers. However, the cycle is a very ambiguous design. Here is what Louis Atenzio writes about cycles in his book Functional Programming in JavaScript : “A loop is a hard control construct that is not easy to reuse and difficult to dock with other operations. In addition, the use of cycles means the appearance of a code that changes with each iteration. ”

Is it possible to get rid of cycles?

The cycle is one of the main structural control structures, and, in fact, we are not going to say that cycles are evil, from which we must get rid of. Our main goal is to reduce the complexity of our own code by minimizing the use of cycles when processing arrays. Is it possible? We offer to find out together.

We have already said that control structures, such as cycles, complicate the code. But why is this so? Take a look at how cycles work in javascript.

In JS, there are several ways to organize loops. In particular, one of the basic types of cycles is

So, there is an array, each element of which we are going to process using the

Notice that we use the counter

This template is so common that in JavaScript there is a simpler way to organize a similar construct - the

The

This pattern of working with arrays, which involves performing certain actions with each element, is quite common. As a result, ES2015 has a new loop design that allows you to forget about the meter. This is the

The code looks much cleaner. Please note that there is neither a counter nor a comparison operation. With this approach, it is not even necessary to refer to a specific element of the array by index. The

If we complete the study of ways to work with arrays and apply

The

The obvious solution is to use two cycles and process arrays in them:

It is a working option. And the code that works is much better than the code that does not solve the task set for it. But two very similar code fragments are not particularly well consistent with the principle of DRY software development. The code can be refactored in order to reduce the number of repetitions.

Following this idea, we create the following function:

It looks much better, but what if there is another function with which we also want to process the elements of the arrays?

Now the

These two functions are incredibly similar. Maybe we can generalize the pattern they follow? Our goal is this: “There is an array and a function. We need to get a new array, in which the results of processing each of the elements of the original array will be recorded using the function ”. This kind of array processing is called “mapping” or “transformation” (mapping in English terminology). Functions that perform such operations are usually called “map”. This is how our version of this function looks like:

Although the cycle is now in a separate function, it did not work out at all. If you go to the end and try to do without cyclic structures at all, you can write a recursive version of the same thing:

Recursive solution looks very elegant. Just a couple of lines of code and a minimum of indents. But recursive implementations of algorithms are usually used with great care, in addition, they are characterized by poor performance in old browsers. And, in fact, we do not need to write the function of implementing the display operation ourselves, unless there is a valid reason. What our

Please note that there are no indents or cycles at all. Of course, when processing data, somewhere in the depths of JavaScript, cycles can be used, but this is not our concern. Now the code turned out to be both compressed and expressive. In addition, it is easier.

Why is this code easier? It may seem like the question is stupid, but think about it. Is it simpler because it is shorter? Not. Compact code is not a sign of simplicity. It is easier because with this approach we have divided the task into parts. Namely, there are two functions that work with strings:

So, the

Consider an example. Suppose there is a list of objects, each of which represents a superhero:

We must find the strongest hero. In order to do this, you can use the

All things considered, this code is not so bad. We loop around the array, storing the object of the strongest of the viewed characters in the

In each of these two examples there is a working variable that is initialized before starting the loop. Then, in each iteration, one element of the array is processed and the variable is updated. In order to isolate the scheme of work even better, we move the operations performed inside the cycles into a function and rename the variables in order to emphasize the similarity of the actions performed.

If everything is rewritten as shown above, the two cycles are very similar. The only thing that distinguishes them is the functions they call and the initial values of the variables. In both cycles, the array collapses to one value. In English terminology, such an operation is called “reducing”. Therefore, we create a

It should be noted that, as in the case of the

If you look at the final result, you may find that the resulting code is not much shorter than what it was before, the savings are quite small. If we used the

At first glance, the

So, there is a

Now suppose that there are two tasks:

It is quite possible to approach the solution of these problems using the good old cycle of

In general, it looks quite decent. But here the repeating pattern is visible to the naked eye. In fact, the cycles are exactly the same, they differ only in

Functions that return only

The way we rewrote the code made it longer. But, after the selection of predicate functions, it became better to see the repeating sections of the program. Create a function that allows you to get rid of these repetitions:

Here, as is the case with the built-in

Why is such an approach much better than using a

And, as is the case with other functions that work with arrays, the use of

Filtering is a very useful operation. But what if you need to find only one superhero from the list? Let's say we're interested in the Black Widow. The

The main problem here is that this solution is not very effective. The

Here, again, I must say that JavaScript has a built-in function that does exactly what you need:

As a result, as before, we managed to express our idea more concisely. Using the built-in

Readers have noticed that it is inefficient to double-pass through the list of characters in the above examples to the

I can not help but notice that this version will be a little more difficult than the one in which the array was passed through twice, but if the array is huge, reducing the number of passes through it can be very useful. In any case, the order of complexity of the algorithm remains O (n).

I suppose the functions presented here are a great example of why thoughtfully chosen abstractions bring benefits and look good in code. Suppose we use built-in functions wherever possible. In each case, the following is obtained:

Please note that in each case compact pure functions are used to solve the problem.

In fact, if you think about all this, you can come to a conclusion that, at the first moment, seems surprising. It turns out that if you use only the four array patterns described above, you can remove almost all loops from the JS code. After all, what is done in almost every loop written in JavaScript? It either processes or constructs an array, or both. In addition, in JS there are other standard functions for working with arrays, you can easily study them yourself. Getting rid of loops almost always allows you to reduce the complexity of programs and write code that is easier to read and maintain.

Dear JavaScript developers, do you have some standard features in mind that allow you to improve the code by getting rid of any common "custom-made" constructions?

If you don’t pay attention to the content of the texts, here’s how a complex code usually looks, the sections of which look like the letters “V” lying on its side, and a simple code whose block, if not taking into account the different lengths of lines, looks like a rectangle.

The more indents, the more difficult the code is.

Constructions that need to be indented will always be in the code, there is no question of completely getting rid of them. However, we are able to reduce the complexity of the programs that we write, due to the rational choice of abstractions for solving the problems we face.

')

Take, for example, arrays. Traditionally for their processing use various types of cycles. The concepts of "array" and "cycle" are inextricably linked in the minds of many programmers. However, the cycle is a very ambiguous design. Here is what Louis Atenzio writes about cycles in his book Functional Programming in JavaScript : “A loop is a hard control construct that is not easy to reuse and difficult to dock with other operations. In addition, the use of cycles means the appearance of a code that changes with each iteration. ”

Is it possible to get rid of cycles?

The cycle is one of the main structural control structures, and, in fact, we are not going to say that cycles are evil, from which we must get rid of. Our main goal is to reduce the complexity of our own code by minimizing the use of cycles when processing arrays. Is it possible? We offer to find out together.

Cycles

We have already said that control structures, such as cycles, complicate the code. But why is this so? Take a look at how cycles work in javascript.

In JS, there are several ways to organize loops. In particular, one of the basic types of cycles is

while . Before going into details, let's get a little ready. Namely, we will create a function and an array with which we will work. // oodlify :: String -> String function oodlify(s) { return s.replace(/[aeiou]/g, 'oodle'); } const input = [ 'John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo', ]; So, there is an array, each element of which we are going to process using the

oodlify function. If you use the while to solve this problem, you get the following: let i = 0; const len = input.length; let output = []; while (i < len) { let item = input[i]; let newItem = oodlify(item); output.push(newItem); i = i + 1; } Notice that we use the counter

i to track the current processed element of the array. It is necessary to initialize it with zero and increment by one in each iteration of the loop. In addition, you need to compare it with the length of the array, with len , in order to know when to stop working.This template is so common that in JavaScript there is a simpler way to organize a similar construct - the

for loop. Such a cycle will solve the same problem as follows: const len = input.length; let output = []; for (let i = 0; i < len; i = i + 1) { let item = input[i]; let newItem = oodlify(item); output.push(newItem); } The

for loop is a useful design, since thanks to it all standard auxiliary operations with the counter are moved to the top of the block. Using while , it is easy to forget about the need to increment counter i , which will start an infinite loop. Definitely, the for loop is much more convenient than the while . But let's slow down and take a look at what our code is trying to achieve. We want to process, using the oodlify() function, each element of the array and put what we have got into the new array. By itself, the counter used to access the elements of the array does not interest us.This pattern of working with arrays, which involves performing certain actions with each element, is quite common. As a result, ES2015 has a new loop design that allows you to forget about the meter. This is the

for…of loop of for…of In each iteration of such a loop, the next element of the array is provided. It looks like this: let output = []; for (let item of input) { let newItem = oodlify(item); output.push(newItem); } The code looks much cleaner. Please note that there is neither a counter nor a comparison operation. With this approach, it is not even necessary to refer to a specific element of the array by index. The

for…of loop takes all the auxiliary operations.If we complete the study of ways to work with arrays and apply

for…of loops everywhere instead of for loops, this will be a good step forward by simplifying the code. But ... we can go further.Array Transformation

The

for…of loop looks much cleaner than the for loop, but with it there are quite a few auxiliary elements in the code. So, you need to initialize the output array and call the push() method at each iteration of the loop. The code can be made even more compact and expressive, but before doing this, let's expand the demo task a bit. What if you need to process two arrays using the oodlify() function? const fellowship = [ 'frodo', 'sam', 'gandalf', 'aragorn', 'boromir', 'legolas', 'gimli', ]; const band = [ 'John', 'Paul', 'George', 'Ringo', ]; The obvious solution is to use two cycles and process arrays in them:

let bandoodle = []; for (let item of band) { let newItem = oodlify(item); bandoodle.push(newItem); } let floodleship = []; for (let item of fellowship) { let newItem = oodlify(item); floodleship.push(newItem); } It is a working option. And the code that works is much better than the code that does not solve the task set for it. But two very similar code fragments are not particularly well consistent with the principle of DRY software development. The code can be refactored in order to reduce the number of repetitions.

Following this idea, we create the following function:

function oodlifyArray(input) { let output = []; for (let item of input) { let newItem = oodlify(item); output.push(newItem); } return output; } let bandoodle = oodlifyArray(band); let floodleship = oodlifyArray(fellowship); It looks much better, but what if there is another function with which we also want to process the elements of the arrays?

function izzlify(s) { return s.replace(/[aeiou]+/g, 'izzle'); } Now the

oodlifyArray() function does not help. However, if we create another similar function, this time izzlufyArray() , we will repeat it again. Nevertheless, let's create such a function and compare it with oodlifyArray() : function oodlifyArray(input) { let output = []; for (let item of input) { let newItem = oodlify(item); output.push(newItem); } return output; } function izzlifyArray(input) { let output = []; for (let item of input) { let newItem = izzlify(item); output.push(newItem); } return output; } These two functions are incredibly similar. Maybe we can generalize the pattern they follow? Our goal is this: “There is an array and a function. We need to get a new array, in which the results of processing each of the elements of the original array will be recorded using the function ”. This kind of array processing is called “mapping” or “transformation” (mapping in English terminology). Functions that perform such operations are usually called “map”. This is how our version of this function looks like:

function map(f, a) { let output = []; for (let item of a) { output.push(f(item)); } return output; } Although the cycle is now in a separate function, it did not work out at all. If you go to the end and try to do without cyclic structures at all, you can write a recursive version of the same thing:

function map(f, a) { if (a.length === 0) { return []; } return [f(a[0])].concat(map(f, a.slice(1))); } Recursive solution looks very elegant. Just a couple of lines of code and a minimum of indents. But recursive implementations of algorithms are usually used with great care, in addition, they are characterized by poor performance in old browsers. And, in fact, we do not need to write the function of implementing the display operation ourselves, unless there is a valid reason. What our

map function does is a task so common that JavaScript has a built-in map() method. If you use this method, the code will be like this: let bandoodle = band.map(oodlify); let floodleship = fellowship.map(oodlify); let bandizzle = band.map(izzlify); let fellowshizzle = fellowship.map(izzlify); Please note that there are no indents or cycles at all. Of course, when processing data, somewhere in the depths of JavaScript, cycles can be used, but this is not our concern. Now the code turned out to be both compressed and expressive. In addition, it is easier.

Why is this code easier? It may seem like the question is stupid, but think about it. Is it simpler because it is shorter? Not. Compact code is not a sign of simplicity. It is easier because with this approach we have divided the task into parts. Namely, there are two functions that work with strings:

oodlify and izzlify . These functions should not know anything about arrays or loops. There is another function - map , which works with arrays. At the same time, she does not care at all what type of data is in the array, or what we want to do with this data. It simply performs any function passed to it, passing it the elements of the array. Instead of mixing everything, we separated the processing of strings and the processing of arrays. That is why the final code was simpler.Array Convolution

So, the

map function is very useful, but it does not overlap all the options for processing arrays that use loops. It is good in cases when, on the basis of a certain array, you need to create a new one having the same length. But what if we need, for example, to stack all the elements of a numeric array? Or if you need to find the shortest line in the list? Sometimes it is required to process an array and, in fact, form a single value based on it.Consider an example. Suppose there is a list of objects, each of which represents a superhero:

const heroes = [ {name: 'Hulk', strength: 90000}, {name: 'Spider-Man', strength: 25000}, {name: 'Hawk Eye', strength: 136}, {name: 'Thor', strength: 100000}, {name: 'Black Widow', strength: 136}, {name: 'Vision', strength: 5000}, {name: 'Scarlet Witch', strength: 60}, {name: 'Mystique', strength: 120}, {name: 'Namora', strength: 75000}, ]; We must find the strongest hero. In order to do this, you can use the

for…of loop: let strongest = {strength: 0}; for (let hero of heroes) { if (hero.strength > strongest.strength) { strongest = hero; } } All things considered, this code is not so bad. We loop around the array, storing the object of the strongest of the viewed characters in the

strongest variable. In order to see more clearly the pattern of working with an array, let's imagine that we still need to figure out the total strength of all the characters. let combinedStrength = 0; for (let hero of heroes) { combinedStrength += hero.strength; } In each of these two examples there is a working variable that is initialized before starting the loop. Then, in each iteration, one element of the array is processed and the variable is updated. In order to isolate the scheme of work even better, we move the operations performed inside the cycles into a function and rename the variables in order to emphasize the similarity of the actions performed.

function greaterStrength(champion, contender) { return (contender.strength > champion.strength) ? contender : champion; } function addStrength(tally, hero) { return tally + hero.strength; } const initialStrongest = {strength: 0}; let working = initialStrongest; for (hero of heroes) { working = greaterStrength(working, hero); } const strongest = working; const initialCombinedStrength = 0; working = initialCombinedStrength; for (hero of heroes) { working = addStrength(working, hero); } const combinedStrength = working; If everything is rewritten as shown above, the two cycles are very similar. The only thing that distinguishes them is the functions they call and the initial values of the variables. In both cycles, the array collapses to one value. In English terminology, such an operation is called “reducing”. Therefore, we create a

reduce function that implements the detected pattern. function reduce(f, initialVal, a) { let working = initialVal; for (let item of a) { working = f(working, item); } return working; } It should be noted that, as in the case of the

map function template, the reduce function template is so widely distributed that JavaScript provides it as an embedded method of arrays. Therefore, your method, if there is no special reason for this, is not necessary to write. Using the standard method, the code will look like this: const strongestHero = heroes.reduce(greaterStrength, {strength: 0}); const combinedStrength = heroes.reduce(addStrength, 0); If you look at the final result, you may find that the resulting code is not much shorter than what it was before, the savings are quite small. If we used the

reduce function, written by ourselves, then, in general, the code would have turned out more. However, our goal is not to write short code, but to reduce its complexity. So, have we reduced the complexity of the program? I can say that reduced. We have separated the loop code from the code that processes the elements of the array. As a result, individual sections of the program have become more independent. The code is easier.At first glance, the

reduce function may seem rather primitive. Most examples of using this function demonstrate simple things, like the addition of all the elements of numeric arrays. However, it is not said anywhere that the value that the reduce returns should be of a primitive type. This can be an object or even another array. When I first realized it, it struck me. You can, for example, write an implementation of a mapping or filtering an array using reduce . I suggest you try it yourself.Array Filtering

So, there is a

map function to perform operations on each element of the array. There is a reduce function, which allows you to compress the array to a single value. But what if you need to extract only some of its elements from an array? To explore this idea, expand the list of superheroes, add some additional data there: const heroes = [ {name: 'Hulk', strength: 90000, sex: 'm'}, {name: 'Spider-Man', strength: 25000, sex: 'm'}, {name: 'Hawk Eye', strength: 136, sex: 'm'}, {name: 'Thor', strength: 100000, sex: 'm'}, {name: 'Black Widow', strength: 136, sex: 'f'}, {name: 'Vision', strength: 5000, sex: 'm'}, {name: 'Scarlet Witch', strength: 60, sex: 'f'}, {name: 'Mystique', strength: 120, sex: 'f'}, {name: 'Namora', strength: 75000, sex: 'f'}, ]; Now suppose that there are two tasks:

- Find all the female characters.

- Find all the heroes whose strength exceeds 500.

It is quite possible to approach the solution of these problems using the good old cycle of

for…of : let femaleHeroes = []; for (let hero of heroes) { if (hero.sex === 'f') { femaleHeroes.push(hero); } } let superhumans = []; for (let hero of heroes) { if (hero.strength >= 500) { superhumans.push(hero); } } In general, it looks quite decent. But here the repeating pattern is visible to the naked eye. In fact, the cycles are exactly the same, they differ only in

if blocks. What if to take out these blocks in functions? function isFemaleHero(hero) { return (hero.sex === 'f'); } function isSuperhuman(hero) { return (hero.strength >= 500); } let femaleHeroes = []; for (let hero of heroes) { if (isFemaleHero(hero)) { femaleHeroes.push(hero); } } let superhumans = []; for (let hero of heroes) { if (isSuperhuman(hero)) { superhumans.push(hero); } } Functions that return only

true or false sometimes called predicates. We use the predicate to decide whether to save the next value from the heroes array in the new array.The way we rewrote the code made it longer. But, after the selection of predicate functions, it became better to see the repeating sections of the program. Create a function that allows you to get rid of these repetitions:

function filter(predicate, arr) { let working = []; for (let item of arr) { if (predicate(item)) { working = working.concat(item); } } return working; } const femaleHeroes = filter(isFemaleHero, heroes); const superhumans = filter(isSuperhuman, heroes); Here, as is the case with the built-in

map and reduce functions, JavaScript has the same thing that we wrote here, in the form of the standard filter method of the Array object. Therefore, it is not necessary to write your own function, without any obvious need. Using standard tools, the code will look like this: const femaleHeroes = heroes.filter(isFemaleHero); const superhumans = heroes.filter(isSuperhuman); Why is such an approach much better than using a

for…of loop? Think about how this can be used in practice. We have a task of the form: "Find all the heroes who ...". As soon as it became clear that the problem can be solved using the standard filter function, the work is simplified. All that is needed is to inform this function exactly which elements interest us. This is done through the writing of one compact function. You do not have to worry about handling arrays, nor about additional variables. Instead, we write a tiny predicate function and the problem is solved.And, as is the case with other functions that work with arrays, the use of

filter allows you to express more information in a smaller amount of code. You do not need to read the entire standard loop code in order to understand what we are filtering. Instead, everything you need to understand is described directly when the method is called.Search in arrays

Filtering is a very useful operation. But what if you need to find only one superhero from the list? Let's say we're interested in the Black Widow. The

filter function can be used to solve this problem: function isBlackWidow(hero) { return (hero.name === 'Black Widow'); } const blackWidow = heroes.filter(isBlackWidow)[0]; The main problem here is that this solution is not very effective. The

filter method scans every element of an array. However, it is known that in the array only one hero is called Black Widow, which means that you can stop after this hero is found. At the same time, predicate functions are convenient to use. Therefore, we write a find function that finds and returns the first matching element: function find(predicate, arr) { for (let item of arr) { if (predicate(item)) { return item; } } } const blackWidow = find(isBlackWidow, heroes); Here, again, I must say that JavaScript has a built-in function that does exactly what you need:

const blackWidow = heroes.find(isBlackWidow); As a result, as before, we managed to express our idea more concisely. Using the built-in

find function, the task of searching for a specific element comes down to one question: “By what sign can we determine that the search element was found?” You don’t need to worry about details.About the reduce and filter functions

Readers have noticed that it is inefficient to double-pass through the list of characters in the above examples to the

reduce and filter functions. Using the spread operator from ES2015 allows you to conveniently combine two functions that are used to fold an array into one. Here is a modified code snippet that allows you to traverse the array only once: function processStrength({strongestHero, combinedStrength}, hero) { return { strongestHero: greaterStrength(strongestHero, hero), combinedStrength: addStrength(combinedStrength, hero), }; } const {strongestHero, combinedStrength} = heroes.reduce(processStrength, {strongestHero: {strength: 0}, combinedStrength: 0}); I can not help but notice that this version will be a little more difficult than the one in which the array was passed through twice, but if the array is huge, reducing the number of passes through it can be very useful. In any case, the order of complexity of the algorithm remains O (n).

Results

I suppose the functions presented here are a great example of why thoughtfully chosen abstractions bring benefits and look good in code. Suppose we use built-in functions wherever possible. In each case, the following is obtained:

- We get rid of loops, which makes the code more compressed and, most likely, easier to read.

- The pattern used is described using the appropriate name of the standard method. That is -

map,reduce,filter, orfind. - The scale of the task is reduced. Instead of self-writing code to handle an array, you only need to specify the standard function to do something with the array.

Please note that in each case compact pure functions are used to solve the problem.

In fact, if you think about all this, you can come to a conclusion that, at the first moment, seems surprising. It turns out that if you use only the four array patterns described above, you can remove almost all loops from the JS code. After all, what is done in almost every loop written in JavaScript? It either processes or constructs an array, or both. In addition, in JS there are other standard functions for working with arrays, you can easily study them yourself. Getting rid of loops almost always allows you to reduce the complexity of programs and write code that is easier to read and maintain.

Dear JavaScript developers, do you have some standard features in mind that allow you to improve the code by getting rid of any common "custom-made" constructions?

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/322850/

All Articles