WAFL File System — NetApp Foundation

In my first post on this blog, I promised to tell you about NetApp "from the technical side." However, before I talk about most of the features found in NetApp systems, I’ll have to talk about the “foundation”, what is the basis of any NetApp storage system — the special structure of data organization that is traditionally called the “WAFL file system” - Write Anywhere File Layout - File Structure with Record Everywhere, if translated literally.

If you find that “for Habr” the text is rather dry, then be patient, it will be more interesting, but I cannot tell you about the structure of what underlies the vast majority of practical “features” of NetApp. In the future, it will be much more likely to refer “for those interested” to a detailed explanation in the following posts about more practical “features”.

One way or another, but almost everything that NetApp can uniquely grows is from the file system invented in the early 90s by David Hitz and James Lau, co-founders of the Network Appliance startup. A good argument for how important and useful in the future development may be the initially competent and thoughtful “architecture” of the product.

But first, why did NetApp need its own file system, what did the existing ones not suit it? This is what one of the creators of NetApp, co-founder and CTO of Dave Hitz, says about this:

')

“Initially, we did not intend to write our file system. It seemed to us that Berkeley FFS was quite suitable for us. But several inherent insoluble problems soon forced us to deal with our own file system.

Testing the integrity of the file system in the event of an abnormal stop (fsck) with FFS at the time was done unacceptably slowly. With the increase in the size of the file system, the situation has deteriorated more and more, which made it almost impossible for our idea to combine all disks into a single disk volume with a single space.

We wanted to make the device as simple as possible. To do this, we had to combine all the disks into a single file system. At that time (we are talking about the beginning of the 90s, approx track), people usually created a separate file system on each individual disk and mounted them together in a common tree, which was inconvenient and non-universal.

Using many disks at once, with a shared file system on them, we would need a RAID. There were two reasons for this. First, by combining multiple disks into a single file system at once, you risked losing the entire file system as a result of the failure of one of the multiple disks. Second, the probability of failure increased with an increase in the number of disks. We needed RAID, and we decided to implement RAID simply as part of our file system.

Previously existing file systems worked on top of RAID, and they didn’t know how the data was placed on the physical level, so they could not optimize their work with this information. Having built our own file system, which knew all the features of data layout on multiple physical disks, and independently implementing RAID, we were able to optimize its work as much as possible.

That's why, after looking at all this, we decided to write our own file system for our device. ”

(who said “with blackjack and whores”?;)

The main principle underlying the functioning of the WAFL file system, which distinguishes it from all existing file systems, may seem a bit paradoxical: a once-written data block in the file is not overwritten. It can only be deleted (cleared), but NOT OVERWRITTEN.

Thus, any data block on the file system can be either “empty”, and then it can be written, or “written”, and then it can be either read or erased when it is no longer referenced by any entry of the overlying structure. Writing (rewriting) into a block that is already occupied with some kind of data is impossible by the internal logic of the file system.

The necessary changes in the contents of the recorded file are “added” to it, to the free space of the file system.

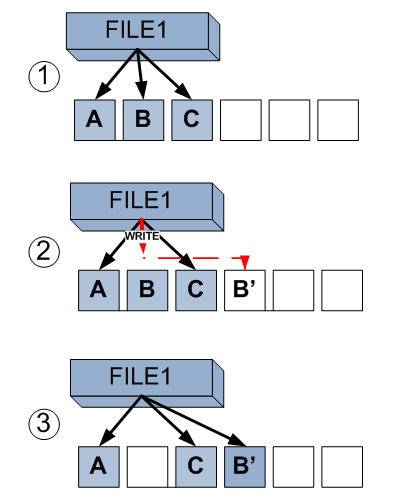

Consider the steps.

In the first step, we see a file that occupies three blocks on the file system: A, B, and C.

Step 2. The program using this file wants to change the data in its middle, which is stored in block B. Opening the file for writing, it changes this data, but FS, instead of changing the data in an already recorded block B, writes them to a completely empty block in the free blocks area .

Step 3. The file system swaps the pointer of the blocks used by the file to the recorded block B 'from block B. And since nobody else refers to block B, it is released and becomes empty.

This kind of model allows us to obtain two important features of use:

- Turn random entries on a storage system into sequentals.

- It is very simple and effective to organize the so-called Snapshots, Snapshots, or instant "snapshots" of the state of the data on the disks.

Let us examine these moments in more detail.

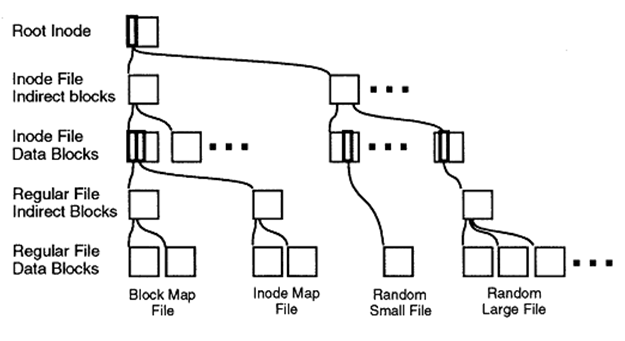

The structure of the organization of the WAFL file system blocks will be clear to everyone familiar with the file system of the “inodes” (inodes) type, of all the numerous “unix” heirs of Berkeley's FFS.

File data blocks are addressed using a structure called 'inode'.

The inode can indicate both the blocks of the file data itself and the intermediate inodes of the “indirect addressing”, forming a kind of “tree”, where in the “root” is the “root inode”, and at the very end of the branches there are blocks of the data itself.

Such a scheme is used by the majority of “Unix” file systems, what is new in WAFL?

Since, as I mentioned above, the contents of the already recorded file system data does not change, and new blocks are only added to the “tree” (and remain there until at least someone is referring to them), it is obvious that having saved the “root” of such tree, root inode, at some point in time, we get a complete “snapshot” of all the data on the disk at that moment. After all, the contents of any already recorded blocks (for example, with the previous contents of the file) are guaranteed not to change.

By saving a single block containing the root inode, we save all the data to which it somehow refers.

This makes it easy to create snapshots of data states on disks.

Such a “snapshot” looks like the complete contents of your entire file system at a certain point in time, the one in which the root inode was saved. Each file on it is available for reading (change it, of course, will not work).

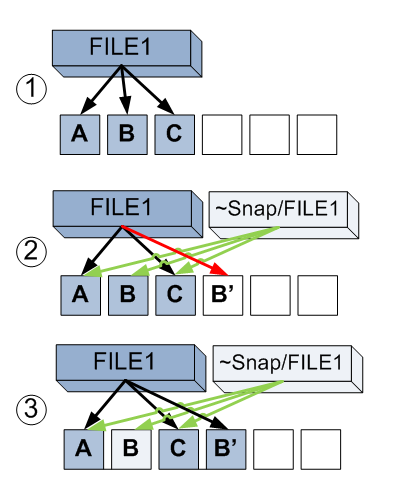

Consider more. In the first step, we again have a file that occupies three blocks of the file system.

In step 2, we create a snapshot. As already explained above, this is simply a copy of the links of the active file system to the blocks occupied by the files. Now each of blocks A, B and C has two links. One from File1, the second from this file from the snapshot made. This is similar to a link in the UNIX file system, but the links do not lead to a file, but to data blocks of this file on the file system. The program changes the data in block B of the file, instead of which new content is recorded in block B '.

Step 3. However, the old block B does not become empty, as it is referenced from the snapshot. Now, if we want to read the contents of File1 before the changes, we can use the file ~ snap / File1, which will turn to blocks A, B and C. And the new content is available when reading File1 itself - A, B 'and C. Thus we have both old, through its snapshot, and new contents of the file system.

As I said above, such an organization of writing to the file system makes it possible to achieve several important things from the point of view of the system:

- Turn the random write operation into a much faster and more efficient storage system sequental write operation (since the entire group of entries in the cache, logically meant for different files in different places, FS can be written into one consecutive segment of empty blocks).

- Record to discs effectively, "full strip".

Unusually, in NetApp systems, they also implemented in their file system, which, I remind you, is also itself a RAID-ohm and volume manager, an unusual type of RAID-RAID type 4. This, I recall, is the “alternation with parity” model, similar to the usual RAID-5, but the parity disk is allocated to a separate physical disk (and not “smeared” throughout the RAID as in type 5).

Usually, RAID-4 is rarely used “in nature”, since it has one, but a very serious drawback - its performance, with its “normal” use, rests on the performance of the parity disk, each write operation on a RAID group has a change operation parity on the disk, which means that no matter how you increase the size of the RAID group, its total performance will still rest on the performance of one disk for writing.

On the other hand, RAID-4, as RAID with a dedicated parity (as opposed to, for example, RAID-5, “with unallocated parity”) has a very solid advantage, which is the ability to expand the capacity of the RAID by adding disks “instantly”. Adding a disk to RAID-4 does not lead to the need to “rebuild a RAID”, immediately after physically inserting the HDD and adding a data disk to an existing RAID, we can start writing to it, extending both the internal WAFL file system and the ones on top of it structures, such as CIFS data volumes, NFS, or LUNs. For the device, initially focused on ease of maintenance, and non-IT companies as customers, this was a big plus.

However, what to do with speed?

It turned out that if we write on RAID-4 consistently, and with “full RAID stripes,” then there is simply no problem with hitting the parity disk. A stripe prepared by one write operation is written to all the disks of the RAID group, then it waits for the next stripe to be assembled, and writes it in one sitting.

What prevents to do also on any file system?

"Random-ness" records. The overwhelming majority of records on modern problems are rather chaotic records on disk space. Since in the classical file system we are forced to rewrite thousands, tens of thousands of data blocks, randomly scattered across the disk space, and usually without any logic from the disk point of view, it becomes extremely difficult to collect the “full stripe” in the cache. To do this, we need to either increase the cache space for writing, or increase the time spent by the data in it, which increases the likelihood that, finally, we will at some point collect the stripe we need in this “puzzle” and will be able to reset it as efficiently as possible. on raid.

However, as you remember, in WAFL we don’t need to drive the pancake heads to re-record a couple (kilo) bytes somewhere in the middle of the file. Need to change data? No problem. Here we have a large empty segment, write everything accumulated at once there, and then move the pointer in the inode to a new place. All waiting by the recording group of bytes at once, not driving on the pancake head, in one step, sequentially (Sequental), leaks to the disks. Recording is completed, and the parity value, precomputed for the stripe, is also recorded in one step on the parity disk.

Of course, nothing is given for free, and turning a random write into a consistent one can in some cases turn a “consistent” reading into a “random” reading. However, practice shows that there are not so many successive reads (as well as consecutive records) in practice, and this “smearing” of a file in a file system affects relatively little on random reading.

In addition, a large reading cache most often successfully copes with this problem.

For the same cases, when the performance of the SEQUENTIAL reading is really important (for example, during backup, which occurs mostly sequentially within a file), a special background optimization process runs on NetApp systems that continuously increases the degree of data “consistency” (as in unix FS) is called 'contiguous'), while the data, evaluated as being consistently located, is collected into longer consecutive "chunks", which facilitates their further sequential reading not (sequental read).

The second feature of WAFL is an unusual “journaling” scheme. Here it must be said that for 1993, when WAFL appeared, logging was still quite rare “features” in file systems, and one of the tasks in creating the AWFL was organizing consistent data storage and a quick restart after a failure. During these years, a “dirty” restart of large file systems on UNIX servers often caused fsck to start for many minutes, and sometimes even hours.

In WAFL, a somewhat unusual scheme is used, with the “journal” being moved to a separate physical device - NVRAM.

NVRAM is an unusual device. Although outwardly, it really resembles a caching controller familiar today, with RAM and a battery for powering it on a turned off system and storing data in it, the principle of its operation is completely different.

The data and commands received by the storage system (for example, NFS operations) are pre-accumulated in NVRAM, after which they are “atomically” transferred to disks, creating so-called Consistency Points (CP), “consistency points”, “consistent” CP is also such a special internal “snapshot”, using the same logical mechanism). The operation of creating a CP occurs either every few seconds, or filling a certain amount of memory in NVRAM (high watermark). Between CPs, the state of the file system is completely consistent, and switching to the next CP is instantly and atomically, so the file system is always in a consistent state, which is similar to how the SQL database is organized.

From the point of view of the system, the data was either entirely successfully recorded or had not yet left NVRAM and did not hit the disks. Since the file system does not overwrite its contents already recorded on the disks, it is very simple to organize “atomicity”, a situation where data has already been changed in part of the blocks, but not in part (for example, a software or hardware failure has occurred) is simply impossible. It is possible that some of the data considered as EMPTY blocks have already been entered, but the “pointer” to the new CP (instant action) that captures the new state of the file system has not yet been moved, it remains in the consistent state of the previous CP, and this is not a problem. If the system’s performance is restored, the recording will continue from the moment it was interrupted at the last successful CP and record the data in the battery-powered NVRAM (up to a week without powering the system as a whole), the data on which the process stopped, and then rearrange the CP . “Half-written” data at the time of failure will be “at the FS level” considered “empty” (and the data in NVRAM will not be considered abandoned) until the pointer to the CP is updated.

That is, the operation of the system is as follows:

NVRAM - system: It's time to write CP!

System - NVRAM: Well, let's go.

We write.

NVRAM system: How are you doing there? All is ready?

NVRAM: Done, chef!

System - File System: Well, God bless you! Plusadin!

File system: (increments its current state pointer to the generated CP) oink!

Unsuccessful write option:

NVRAM - system: Everything is lost, chef! Disks do not respond! Chef? Are you here?

System (boot): Phew, was it a shoeto? NVRAM! Stand still! File system - nobody goes anywhere! Use the last valid CP record before crashing! NVRAM - now repeat the last write operation on which you interrupted from the very beginning!

NVRAM: Yes, chef!

Such an ingenious scheme makes the file system extremely holistic and stable, to the extent that many practical administrators over the years of NetApp systems have never encountered any incidents of integrity violations and the need to “run chkdsk (fsck for the inhabitants of the neighboring OS galaxy; ) ".

In parentheses, I note that the WAFL integrity monitoring system in the system is, of course, if you need them.

You can read more about the device and the principles of WAFL operation from the author’s publication “Creating a Specialized File System for the NFS File Server”, published in 1994 in the USENIX magazine, and describing the basic principles of building WAFL. On the website of the Russian distributor of Netwell , in the regularly updated library of translated Best Practices, you can download a translation of this document.

In the next article I will talk about how WAFL managed to implement data deduplication that does not slow down the storage system.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/99832/

All Articles