Cat pasture

Karl Vogel’s book “Producing open source software” has a wonderful cover (see above). It shows a lot of small arrows of different sizes pointing to the right, and a large yellow arrow, in my opinion, showing the final effect. She as if tells us: if all the horses are dragged in one direction, it will be possible to move the whole house to another place.

I understand it this way, because it reminds me of a bunch of different drawings that were made in physics classes. If the ball hits another here and under that angle, where will the boot fall? Something like this.

This is a beautiful picture, and this is how I imagined open source , until I became involved in it. All people are dragging the project in one direction to make an encyclopedia, or an operating system. But, I tell you, this is not at all the case until the project has grown

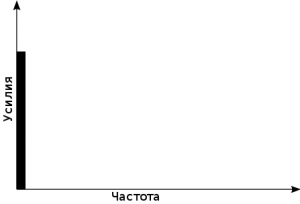

First, the size of the arrows. The distribution of efforts in joint projects can vary dramatically. When a project is just beginning, efforts are often distributed like this:

')

Stage 1. Schedule of distribution of efforts of one person.

What does it mean? This means that one person does the most. With very low frequency indicators (only one person!). A lot of effort, because this person is engaged in all coding, makes the site work, responds to mail, fights enemy projects with stupid ideas, thinks up how to do better, and so on. This is the most critical phase of the life of projects, and that is why many projects are synonymous with the person who started them. Or at least the myth of who started it, because successful projects attract people who want everything to go well because of them. Linux, Linus. Wikipedia, Jimbo Wales. Mono.NET , Miguel de Icaza. Debian, Jan Murdoch.

There are thousands of small projects successfully led by their founders. File utilities, mouse drivers, deployment tools , graphical utilities, and so on. When they grow up, in most cases they retain the original authors, because otherwise they tend to go inadequate . The committees are poorly adapted to the management of large distributed projects that rely on free time (!) People. Generous dictators, as a rule, work well, and when they fail, the project forks or dies, and hundreds of new flowers bloom .

Think about Debian and Ubuntu in this context. If you do not know what it is, then it does not matter.

The next stage of the project depends largely on the temperament of the person who started it. Often he does not accept new ideas, or deals with them only for the sake of his own fame (read: money). Either he is bored, or he wants to control everything, or he simply doesn’t have enough time. There are millions of reasons. When OpenStreetMap was just beginning, there were at least two similar projects I knew about. One of them is geowiki.com , started by Richard Fairhurst (by Potlatch - kom.) With friends. It was (and is) a great site, probably taking a lot of time to get done, and had no connection with the community (mailings and all that). This led to stagnation, because no one could take part and all data, source code and tools were closed.

Secondly, free-map.org.uk , which Nick Whitelegg is still involved in. The site is focused on pedestrians. Here in England, there is a large community of people who walk on foot, using the right of way (which often crosses private land). The free-map indulged these people and Nick spent a lot of energy on them, but basically this project is managed by Nick, due to his narrow focus. Nick has thousands of good ideas, but only Nick can bring them to life. In free time.

When OSM was just beginning, he had to overcome light years in order to reach the level of these projects; but, like them, he essentially rejected geo-dogmas. Today, Nick and Richard are key members of OpenStreetMap.

After the very first talk about OSM, freemap was created. She was implanted from top to bottom, using all the latest standards and in general, did not lead anywhere (except for good intentions) - she concentrated on technology, not on the community.

- Community is everything. OSM never wanted to make a map. And not even the most beautiful card. And not the best. And not the fastest. Not even a map that would work 3 hours out of 24. What he did (and does) - simplifies the creation of maps both socially and technically.

- The second cornerstone was the rejection of customs. All code is open. All data is open. Everything is as open as possible so as not to divulge the secrets of private life.

These two things have become key, as well as the fact that separated the OSM from other projects. You can easily agree with them, and talk and spread. The third component is not.

- Only those who actually do something can speak. The rest can get out.

For a good two years OSM was full of people with cool ideas on how to build a spacecraft. I like spaceships. I like flying cars. I hurt every time I see a DeLorean that doesn’t soar vertically upwards. But in order to build a spacecraft, we need highly paid specialists from NASA. And mechanics, to be sure that it will take off. And the team on the ground just in case. This is all, of course, good things, but they are rarely available for free, in someone's free time.

OSM, on the other hand, is Buzz Laitear's cardboard spaceship. He looks like a spaceship. If you throw it up and squint at it for a couple of seconds, then it’s kind of like flying. It is fastened with twine and glue. Crackler, in short. But on the other hand, it worked. Anyone can make a contribution, anyone can get data. It was the only project with a simple API that anyone could contact.

Constantly put forward proposals to attach to it jet engines (this, by the way, was discussed for the "Space Shuttle") or intergalactic beaters of space. Most of these people were told to get out, unless they had developed, built, and attached rockets.

Why such a tough attitude? Because it is difficult to do something similar to OSM. It takes love, time and attention for long periods of time. Therefore, nerves can play pranks when a space cadet lands near your cardboard ship and says that you do everything wrong, because they read something like this in a book and it was written wrong there. If three space cadets are gathered around you, arguing about the three different architectures of subspace engines, make a sail and tell them all to get out.

Let's go back to the arrows.

At this stage, the project still has a leader, but there are already a lot of users and random people writing a significant amount of code. OSM in this regard is slightly unusual, because users are in some sense more important for it than programmers. They are there, on Sunday's rain, for free, they draw some terrible households. Without them you would not have a card. On the other hand, the simplest workable thing will do as long as you have users drawing a map.

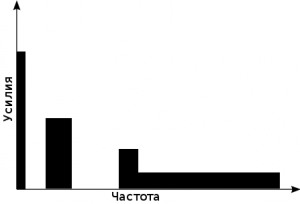

Stage 2. Irregular distribution of efforts

So we come to the second stage. The founder remains on the left of the chart, being a person who spends a lot of time on it. But there is also a bunch of people doing key things. In the case of OSM, they were a man named Imi, who made a terrific JOSM map editor, a man named Andy, and someone named 80n (yes, exactly) who drew a lot of details and started working on the OSM ontology . It does not have an ontology as such, so let’s take it for now as a metaphor. The more the frequency grows, the more there are people involved in small things. Painting a couple of streets. Correcting weird bugs. Making the project famous.

Notice that the area of the figure under the chart represents, roughly, the amount of work done per unit of time. Note that the two right-hand rectangles together have a larger area than the left. In general, they do more work.

There is a drawback - the process on the right moves in jerks. Someone draws a whole city and disappears. Someone makes a whole complex for editing, and then he has a girlfriend. So speakers move in different directions with time. Who knows what will happen to the project next month?

Stage 3. Smoothing the Effort / Frequency schedule

Gradually, with the arrival of a large number of new people, the distribution is smoothed out.

Albeit incorrectly mathematically, this graph is often called “long-tailed”. The efforts of several individuals who are engaged constantly are equivalent to the sum of thousands of people spending a minute a day. OSM has not yet come to this state, but it is getting closer every day. This leads to a special set of lengths of arrows - a set of short and several large ones.

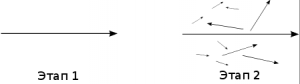

What about direction? After reviewing our stages, I think the first two look like this:

Yes, some of the arrows lead in the opposite direction.

So in the first stage, we have one founder. On the second there are people who consider the whole undertaking to be foolish, or start competing projects - therefore, they point the other way. People with different goals appear, focusing on different things - so some are drawn at an angle. Different size, because they put different efforts.

Well, in the end, as the schedule starts to smooth out, and ideas with technologies become generally accepted, we will see something more reminiscent of the cover of that book.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/85258/

All Articles