Knowledge is power. History of information retrieval systems

As the Habrination rule “Habr is not a place for copy-pasters,” therefore, a small introduction is needed. This article was once a long time ago published in the Mobi magazine, but since the author is me, I think this cannot be considered a copy-paste =)

Especially since here is the “original”, before the editorial changes. Plus it or a minus - we will look on comments. =)

In general, the article is devoted to the development of information retrieval systems ranging from the library catalogs of the ancient world and ending with the appearance of hypertext.

Since ancient times, writing is one of the most reliable ways to preserve the scientific and cultural heritage of the people. The kingdoms of the Hittites and Assyrians have already disappeared from the face of the earth, the Persian empire is no longer there, the famous Babylonia has disappeared, Carthage has been destroyed, Phenicia has sunk into oblivion ... day, perpetuating the names of people who lived thousands of years ago. Books, parchments, papyrus scrolls and clay tablets have been kept in temple and palace libraries since ancient times. Moreover, these cultural treasures were valued no less than gold. Absolutely normal practice of the ancient conquerors was the assignment of enemy libraries, and then - a thorough study, the translation of their contents and inclusion in their own repositories of knowledge. However, before any large library sooner or later there was a serious problem of orientation in the ocean of information.

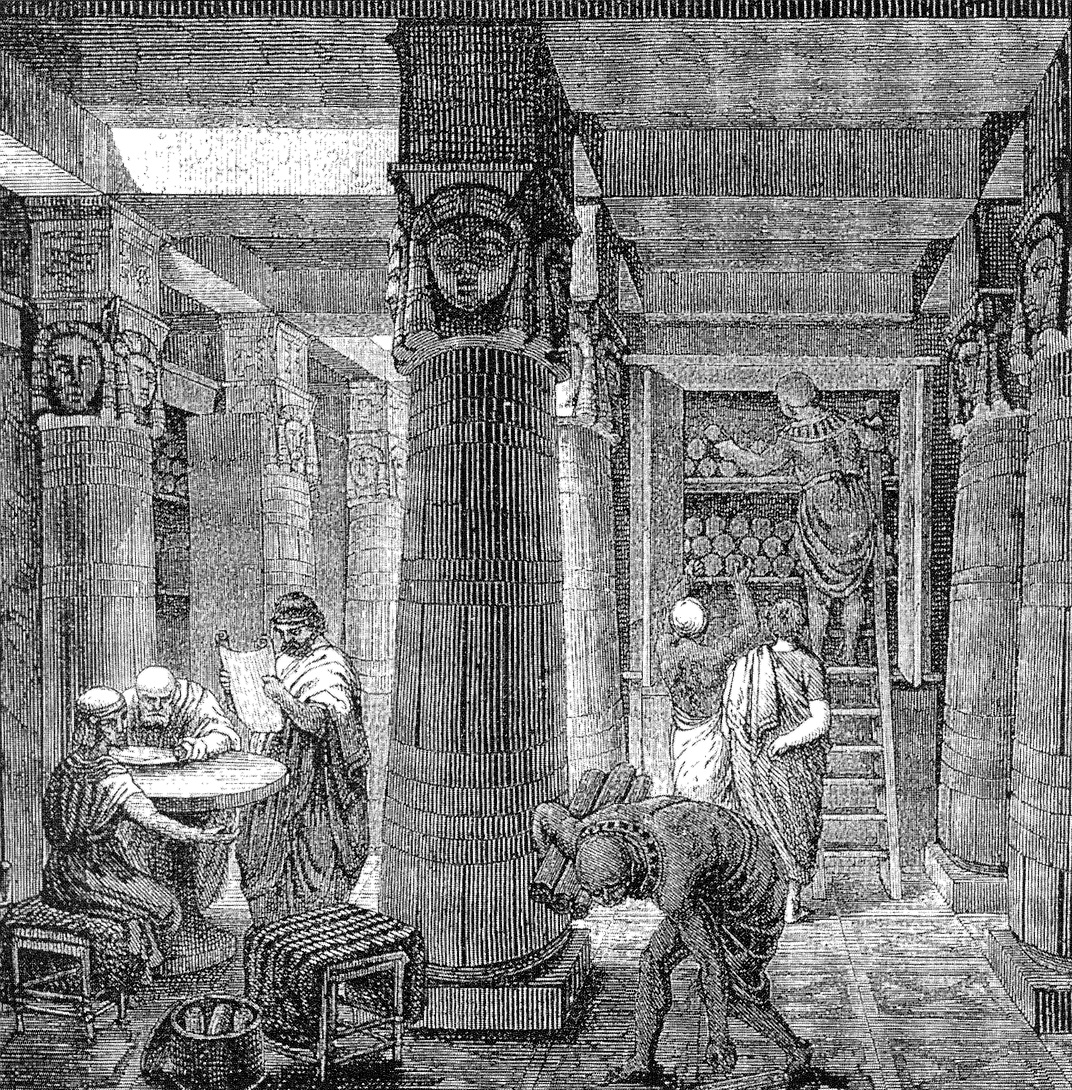

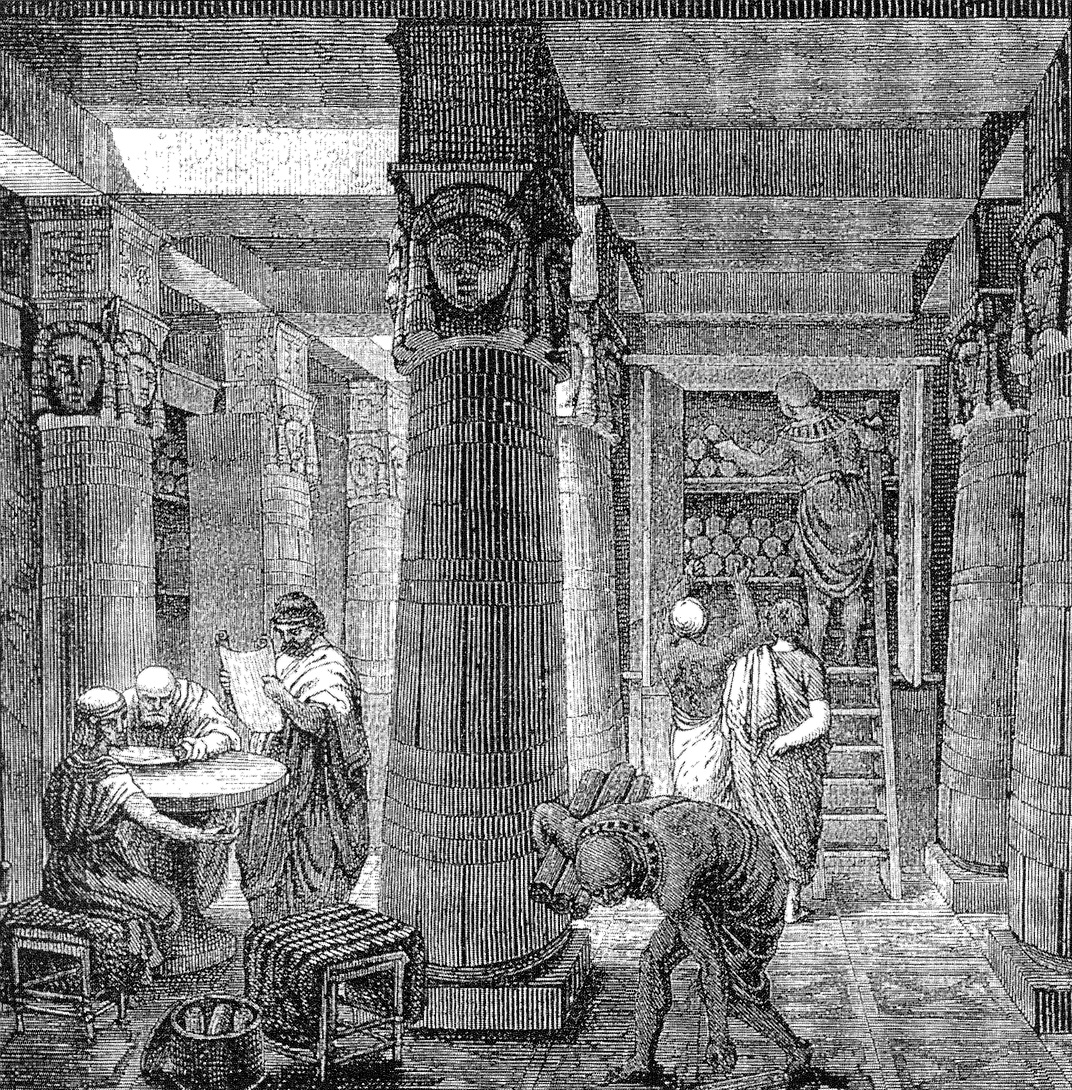

Great Library

In 323 BC The great conqueror Alexander the Great died. A year later, he created a grand empire disintegrated. Provinces became independent kingdoms, headed by generals of the army of Alexander. Some of them were quickly overthrown, but others became the founders of the new royal dynasties. Actually, the secret by which the foreigners (Greeks, Macedonians) were able to keep at the head of the states conquered by Alexander, in most cases, was extremely simple: "To rule a people, you must first learn and understand it." This unshakable axiom of Alexander, obviously learned by him from the lessons of Aristotle, helped Ptolemy I, the founder of the new dynasty of the kings of Egypt, to remain in power and the Macedonian. He was an educated and very intelligent man. Being a passionate admirer of literature, he founded the Great Library of Alexandria, which became the greatest center of science of the whole ancient world.

It was a whole complex called mouseĩon which, in addition to the library, included living quarters, dining rooms, reading rooms, botanical and zoological gardens, an observatory, and classrooms. Later, space for astronomy and medicine was also added. In fact, the Alexandria mouseĩon was a unique combination of a research institute and a library. Here was everything that the ancient philosopher, doctor, astronomer or engineer could wish for. All significant scholars of antiquity were invited to the library generously financed from the state treasury. Among them are Euclid, Archimedes, Eratosthenes, Aristarchus of Samothrace, Demetrius of Falernsky, etc. The table, the shelter, the necessary tools, and, of course, books were at their service ...

The Ptolemaic dynasty acquired books to replenish the grand library with stunning zeal. This was both a passion and government policy of the kings of Egypt. If it was impossible to buy books, they were abducted or taken away by force. Ptolemy I, after the death of Alexander, somehow managed to get some of the original works of Aristotle (there is a version that he simply stole them). Ptolemy II bought all the remaining works of Aristotle. Ptolemy III sent his agents to all parts of the Mediterranean, who bought unknown manuscripts to supplement the Great Library. The same Ptolemy III appealed to the rulers of the civilized world with a request to lend valuable books for copying. A whole staff of copyists, who worked at the library, in the shortest possible time made copies of the works of Euripides, Aeschylus, Sophocles and other ancient scholars and philosophers. After this, the originals of Ptolemy were left in the library, returning only copies.

All books on ships entering the port of Alexandria were also necessarily removed by the customs services and copied.

Thus, according to various data, from 400 to 700 thousand documents were collected in the Alexandria Library.

With such a huge number of books, mouse-on faced a serious problem of structuring huge amounts of information. An entire service was created at the library, which takes into account existing and new books. All documents were entered into catalogs with an indication of where they came from, with the name of the former owner, the name of the author and a brief abstract. There were several voluminous multi-volume catalogs in which all the books were sorted according to different principles. For example, in one catalog, the manuscripts were grouped by subject content: medicine, philosophy, astronomy, etc. In the other - at the place of admission. For example, all the books received from ships arriving at the port of Alexandria were called the “ship library”, where interesting novelties and rare foreign books could be found (by the way, the invaluable works of the Infectious Diseases Hippocrates).

In the third catalog of the book were listed in alphabetical order by the name of the author, in the fourth - by the name of the manuscript, etc.

Thanks to this unique system, it was relatively easy to find the necessary document among hundreds of thousands of books, it was enough just to rummage in the appropriate catalog. If the reader needs a specific manuscript and he knows for sure its name, he looks at the alphabetical catalog. If he is looking for something more abstract, for example, methods of treating poisoning, he is studying a catalog of medical books. Finally, an elderly bibliophile, who has already re-read everything that could have caused his interest, visits the library every day, where he looks through the catalog of new acquisitions.

In 273 AD The great library was destroyed during the suppression of the rebellion of Queen Zenobia. The surviving books were taken to Constantinople, but the system of subject catalogs “burned out” along with the library. New scientific and cultural centers and large libraries found this system too time consuming.

')

Dark Ages

During the Middle Ages, libraries existed mainly in monasteries. Here also worked the scriptoria (lat. Scriptorium from the scriptor - scribe, copyist) where the writings of the Fathers of the Church, the Scripture and the works of ancient authors were copied. Despite the substantial amount of documents stored in some libraries, in none of them, even in the largest one there were no alphabetical or other systematic catalogs. The only person able to navigate the monastic library was, in fact, a librarian. He, and only he, possessed some secret search for information in manuscripts.

Most likely, each librarian had his own “navigation” system based on secret tags, entries in a personal catalog, or some other way of structuring books. However, this “secret” was not advertised. The ability to navigate in the monastic library made the “keeper of knowledge” indispensable and gave a certain power over ordinary monks. In a word - a sure piece of bread and a mystical halo to boot.

This state of affairs persisted until the 15th century, when, in connection with the development of banking, accounting and printing, a system of indices was born. Initially, the indices were used to unify and standardize workflow and facilitate the search for the desired paper in bank books. Somewhat later, indexing was adopted in libraries and all bookprints. It was then that the rules for design of books and documents began to emerge. Before the advent of typography and indexes, there were no standards: each manuscript was unique, each book was framed in its own way, basically, as the scribe's fantasy tells. Often, the scribes forgot (or simply did not consider it necessary) to indicate the authorship, make mistakes or allow themselves some liberties, interpreting the original. That is why the scholars of the Renaissance so desperately searched for the originals of ancient authors, quite rightly mistrusting the monastic copies.

The introduction of a system of indices and more or less uniform rules for the design of books, firstly, dramatically reduced the number of information distortions when copying, and secondly, it made it relatively easy to navigate a great variety of books.

Index - lat. "Pointer", "list"

So, indexing is the sorting of information (books, for example) according to some formal principles. Until the mid-19th century, most libraries used their own classification systems, which created certain difficulties. For example, a scientist all his life enjoyed books from the Bodleian library at Oxford University. Then, some urgent need forced him to contact the British Library in London. And there is another indexing system! And in it, which is typical, you must first properly understand, before you take up the search for the necessary information.

In 1873, Melville Dewey developed the so-called “Dewey Decimal Classification”. In this system, numerical indices were used to denote the subject matter of the publication. The hierarchical system made it easy enough, moving from general to specific to find the desired publication. For example, indexes 500-590 mean books related to the section "Natural Sciences and Mathematics". The indices included in this interval have a narrower meaning: 510 - “mathematics”, 520 - “astronomy”, 530 - “physics”, 540 - “chemistry”. Each of these subsections is divided into ten groups, for example, 541 is “physical and theoretical chemistry”, 542 - “technology, equipment, materials”, 546 - “inorganic chemistry”, 547 - “organic chemistry”. These groups also have divisions: 541.2 - “theoretical chemistry”, 541.3 - “physical chemistry”, etc. Thus, a person who knows how to navigate the index system will always find the book he needs, if there is one in the library, of course. This, incidentally, is a feature of the Dewey decimal classification. Each library may, within certain limits, modify the system of indices depending on the capabilities of its stock. For example, one library has a large supply of cat literature, so it can detail all information during indexing by entering sections, for example, 636.82 - “short-haired cats”, 636.83 - “long-haired cats”, 636.825 - “Asian short-haired cats”, etc. And in the other library there is almost nothing about cats, so it is limited to one single index: 636.8 - “cats”. On the one hand, this feature of the Dewey system is considered an important advantage, providing a certain classification flexibility. On the other hand, this is its main drawback, since the differences in the indices in different institutions create a certain confusion, in addition, each library must independently index the books available.

Ideally, the classification system for books should be uniform throughout the world. To this end, in 1895, on the basis of Dewey's decimal classification, a new system was developed, called the Universal Decimal Classification or UDC. The main difference between UDC is that thanks to it, it is possible to determine, first of all, the content of the book, and not its location in the library repository. It is a rigidly structured system, covering the whole body of knowledge, and built on the hierarchical principle of division from general to specific using a digital decimal code. Currently, the UDC is widely used in Europe, Latin America, Russia and Japan, which greatly simplifies the process of finding foreign sources of information.

The indexing system has become an important and very timely invention, allowing, finally, to systematize the entire gigantic amount of knowledge accumulated by mankind.

The birth of hypertext

The indexing system greatly facilitated the search for information, but it also had its drawbacks. We all have ever come across situations where an unfamiliar or incomprehensible term (process description, phenomenon, formula) comes across in a book that requires further clarification. In this case, you have to go back to the library and rummage through the books in search of an answer to the question. There were mountains of dictionaries and encyclopedias, into which they tried to cram as much reference information as possible, but this did not solve the problems in general.

In 1945, the American engineer Vannevar Bush (Vannevar Bush) wrote an article in the popular science journal “How we can think.” In it, he put forward the idea of a machine for storing and structuring information with the possibility of its replenishment, rewriting and transfer to other terminals. Opportunity is very similar to the modern computerized workplace, is not it? However, the Vannevar Bush machine, which he called the Memex, was completely analog. (perhaps the word “mechanical” will be clearer, although it is not quite right)

Memex was a desk with projector screens to display information. To control the machine used the keyboard, as well as additional buttons and levers. All information was stored on microfilm, access to which was carried out using a special mechanism by a command from the keyboard. Memex was also equipped with a subsystem capable of using the dry photo process to record on microfilm new data and create new text documents.

However, the main feature of the machine was not how to store information, but how to access it. Bush suggested that special notes be written in the margin of the document, which could be used to switch between certain documents. In fact, it was a cross-reference system, a prototype of the modern hypertext.

Memex was never built, but the ideas embodied in it twenty years later received an unexpected development.

"Mongolian utopia"

The term "hypertext" was first proposed by the scientist Ted Nelson (Theodor Holm Nelson) in 1965 to refer to "text branching out or performing actions upon request." The most vividly the meaning of the idea is characterized by modern hyperlinks. When a certain keyword or concept (link) is encountered in a text for a specific query (for example, by clicking the mouse), a new document is logically linked logically to the activated link. This allows you to quickly move between documents, quickly getting all the necessary information for work.

Such a system was laid in the memex car of the Wanver Bush, but due to technical limitations, it was never implemented.

Ted Nelson, already relying on the emerging electronic computers, developed this idea, as a result of which the concept of "hypertext" appeared. However, another project, Xanadu, brought him worldwide fame and a place in the history of computing technology. The idea, unfortunately, is practically unrealizable, but it is no less beautiful.

So, Xanadu is a project of a global repository of information hosted in near-earth orbit. With the help of microfilming technologies, it was supposed to create the most complete archive of the entire written, artistic, and technical culture of mankind. Books, drawings, textbooks, works of art and other media recorded on microfilms were located on geostationary satellites capable of exchanging information with each other and with terminals on the ground over the radio channel. The archive could also be replenished with microfilm recorders and a certain stock of blank media located on satellites. In addition, Xanadu was the first hypertext project. That is, in addition to, in general, the revolutionary idea of storing information, he was also a pioneer in the implementation of new ways to search for it.

Most likely, Nelson himself was well aware of the unrealizability of such a project, but he believed (and, by the way, continues to believe so far) that with time he will be implemented.

There was another idea in the Xanadu project. Maybe not as obvious as its technical novelty, but no less important. The project was born in the 60s of the twentieth century, at the very height of the Cold War, when the world was sometimes separated from a nuclear catastrophe in a matter of hours. The 1962 Caribbean crisis alone is worth something.

In the event of a global nuclear war, mankind, perhaps, will survive. But it will inevitably be thrown back hundreds of years ago. Thousands of documents, scientific papers, technologies and works of art will disappear forever. But the storages on the geostationary Xanadu satellites will survive. With their help, humanity could quickly recover the most valuable information after such a catastrophe.

"Who owns the information - he owns the world"

Libraries, for several thousand years, have been the most powerful centers of education, as well as the storage, creation and use of information resources. , . , . , , , , .

. , . , , : , , , , … , .

Especially since here is the “original”, before the editorial changes. Plus it or a minus - we will look on comments. =)

In general, the article is devoted to the development of information retrieval systems ranging from the library catalogs of the ancient world and ending with the appearance of hypertext.

Since ancient times, writing is one of the most reliable ways to preserve the scientific and cultural heritage of the people. The kingdoms of the Hittites and Assyrians have already disappeared from the face of the earth, the Persian empire is no longer there, the famous Babylonia has disappeared, Carthage has been destroyed, Phenicia has sunk into oblivion ... day, perpetuating the names of people who lived thousands of years ago. Books, parchments, papyrus scrolls and clay tablets have been kept in temple and palace libraries since ancient times. Moreover, these cultural treasures were valued no less than gold. Absolutely normal practice of the ancient conquerors was the assignment of enemy libraries, and then - a thorough study, the translation of their contents and inclusion in their own repositories of knowledge. However, before any large library sooner or later there was a serious problem of orientation in the ocean of information.

. , , 4500 . 13 .. II 20000 , , .. . , , . , 612 .. .Great Library

In 323 BC The great conqueror Alexander the Great died. A year later, he created a grand empire disintegrated. Provinces became independent kingdoms, headed by generals of the army of Alexander. Some of them were quickly overthrown, but others became the founders of the new royal dynasties. Actually, the secret by which the foreigners (Greeks, Macedonians) were able to keep at the head of the states conquered by Alexander, in most cases, was extremely simple: "To rule a people, you must first learn and understand it." This unshakable axiom of Alexander, obviously learned by him from the lessons of Aristotle, helped Ptolemy I, the founder of the new dynasty of the kings of Egypt, to remain in power and the Macedonian. He was an educated and very intelligent man. Being a passionate admirer of literature, he founded the Great Library of Alexandria, which became the greatest center of science of the whole ancient world.

It was a whole complex called mouseĩon which, in addition to the library, included living quarters, dining rooms, reading rooms, botanical and zoological gardens, an observatory, and classrooms. Later, space for astronomy and medicine was also added. In fact, the Alexandria mouseĩon was a unique combination of a research institute and a library. Here was everything that the ancient philosopher, doctor, astronomer or engineer could wish for. All significant scholars of antiquity were invited to the library generously financed from the state treasury. Among them are Euclid, Archimedes, Eratosthenes, Aristarchus of Samothrace, Demetrius of Falernsky, etc. The table, the shelter, the necessary tools, and, of course, books were at their service ...

The Ptolemaic dynasty acquired books to replenish the grand library with stunning zeal. This was both a passion and government policy of the kings of Egypt. If it was impossible to buy books, they were abducted or taken away by force. Ptolemy I, after the death of Alexander, somehow managed to get some of the original works of Aristotle (there is a version that he simply stole them). Ptolemy II bought all the remaining works of Aristotle. Ptolemy III sent his agents to all parts of the Mediterranean, who bought unknown manuscripts to supplement the Great Library. The same Ptolemy III appealed to the rulers of the civilized world with a request to lend valuable books for copying. A whole staff of copyists, who worked at the library, in the shortest possible time made copies of the works of Euripides, Aeschylus, Sophocles and other ancient scholars and philosophers. After this, the originals of Ptolemy were left in the library, returning only copies.

All books on ships entering the port of Alexandria were also necessarily removed by the customs services and copied.

Thus, according to various data, from 400 to 700 thousand documents were collected in the Alexandria Library.

With such a huge number of books, mouse-on faced a serious problem of structuring huge amounts of information. An entire service was created at the library, which takes into account existing and new books. All documents were entered into catalogs with an indication of where they came from, with the name of the former owner, the name of the author and a brief abstract. There were several voluminous multi-volume catalogs in which all the books were sorted according to different principles. For example, in one catalog, the manuscripts were grouped by subject content: medicine, philosophy, astronomy, etc. In the other - at the place of admission. For example, all the books received from ships arriving at the port of Alexandria were called the “ship library”, where interesting novelties and rare foreign books could be found (by the way, the invaluable works of the Infectious Diseases Hippocrates).

In the third catalog of the book were listed in alphabetical order by the name of the author, in the fourth - by the name of the manuscript, etc.

Thanks to this unique system, it was relatively easy to find the necessary document among hundreds of thousands of books, it was enough just to rummage in the appropriate catalog. If the reader needs a specific manuscript and he knows for sure its name, he looks at the alphabetical catalog. If he is looking for something more abstract, for example, methods of treating poisoning, he is studying a catalog of medical books. Finally, an elderly bibliophile, who has already re-read everything that could have caused his interest, visits the library every day, where he looks through the catalog of new acquisitions.

In 273 AD The great library was destroyed during the suppression of the rebellion of Queen Zenobia. The surviving books were taken to Constantinople, but the system of subject catalogs “burned out” along with the library. New scientific and cultural centers and large libraries found this system too time consuming.

')

Dark Ages

During the Middle Ages, libraries existed mainly in monasteries. Here also worked the scriptoria (lat. Scriptorium from the scriptor - scribe, copyist) where the writings of the Fathers of the Church, the Scripture and the works of ancient authors were copied. Despite the substantial amount of documents stored in some libraries, in none of them, even in the largest one there were no alphabetical or other systematic catalogs. The only person able to navigate the monastic library was, in fact, a librarian. He, and only he, possessed some secret search for information in manuscripts.

Most likely, each librarian had his own “navigation” system based on secret tags, entries in a personal catalog, or some other way of structuring books. However, this “secret” was not advertised. The ability to navigate in the monastic library made the “keeper of knowledge” indispensable and gave a certain power over ordinary monks. In a word - a sure piece of bread and a mystical halo to boot.

This state of affairs persisted until the 15th century, when, in connection with the development of banking, accounting and printing, a system of indices was born. Initially, the indices were used to unify and standardize workflow and facilitate the search for the desired paper in bank books. Somewhat later, indexing was adopted in libraries and all bookprints. It was then that the rules for design of books and documents began to emerge. Before the advent of typography and indexes, there were no standards: each manuscript was unique, each book was framed in its own way, basically, as the scribe's fantasy tells. Often, the scribes forgot (or simply did not consider it necessary) to indicate the authorship, make mistakes or allow themselves some liberties, interpreting the original. That is why the scholars of the Renaissance so desperately searched for the originals of ancient authors, quite rightly mistrusting the monastic copies.

The introduction of a system of indices and more or less uniform rules for the design of books, firstly, dramatically reduced the number of information distortions when copying, and secondly, it made it relatively easy to navigate a great variety of books.

Index - lat. "Pointer", "list"

So, indexing is the sorting of information (books, for example) according to some formal principles. Until the mid-19th century, most libraries used their own classification systems, which created certain difficulties. For example, a scientist all his life enjoyed books from the Bodleian library at Oxford University. Then, some urgent need forced him to contact the British Library in London. And there is another indexing system! And in it, which is typical, you must first properly understand, before you take up the search for the necessary information.

In 1873, Melville Dewey developed the so-called “Dewey Decimal Classification”. In this system, numerical indices were used to denote the subject matter of the publication. The hierarchical system made it easy enough, moving from general to specific to find the desired publication. For example, indexes 500-590 mean books related to the section "Natural Sciences and Mathematics". The indices included in this interval have a narrower meaning: 510 - “mathematics”, 520 - “astronomy”, 530 - “physics”, 540 - “chemistry”. Each of these subsections is divided into ten groups, for example, 541 is “physical and theoretical chemistry”, 542 - “technology, equipment, materials”, 546 - “inorganic chemistry”, 547 - “organic chemistry”. These groups also have divisions: 541.2 - “theoretical chemistry”, 541.3 - “physical chemistry”, etc. Thus, a person who knows how to navigate the index system will always find the book he needs, if there is one in the library, of course. This, incidentally, is a feature of the Dewey decimal classification. Each library may, within certain limits, modify the system of indices depending on the capabilities of its stock. For example, one library has a large supply of cat literature, so it can detail all information during indexing by entering sections, for example, 636.82 - “short-haired cats”, 636.83 - “long-haired cats”, 636.825 - “Asian short-haired cats”, etc. And in the other library there is almost nothing about cats, so it is limited to one single index: 636.8 - “cats”. On the one hand, this feature of the Dewey system is considered an important advantage, providing a certain classification flexibility. On the other hand, this is its main drawback, since the differences in the indices in different institutions create a certain confusion, in addition, each library must independently index the books available.

Ideally, the classification system for books should be uniform throughout the world. To this end, in 1895, on the basis of Dewey's decimal classification, a new system was developed, called the Universal Decimal Classification or UDC. The main difference between UDC is that thanks to it, it is possible to determine, first of all, the content of the book, and not its location in the library repository. It is a rigidly structured system, covering the whole body of knowledge, and built on the hierarchical principle of division from general to specific using a digital decimal code. Currently, the UDC is widely used in Europe, Latin America, Russia and Japan, which greatly simplifies the process of finding foreign sources of information.

The indexing system has become an important and very timely invention, allowing, finally, to systematize the entire gigantic amount of knowledge accumulated by mankind.

19- , . , , « » , .

, . 19- . , (, ) . , . , , . . -, : , ( ) . -, . – , 70 16 (!) . – . -, . , 500, 1000 . , – . , .

. , , ( ) . . , , .

, .The birth of hypertext

« . , , »

The indexing system greatly facilitated the search for information, but it also had its drawbacks. We all have ever come across situations where an unfamiliar or incomprehensible term (process description, phenomenon, formula) comes across in a book that requires further clarification. In this case, you have to go back to the library and rummage through the books in search of an answer to the question. There were mountains of dictionaries and encyclopedias, into which they tried to cram as much reference information as possible, but this did not solve the problems in general.

In 1945, the American engineer Vannevar Bush (Vannevar Bush) wrote an article in the popular science journal “How we can think.” In it, he put forward the idea of a machine for storing and structuring information with the possibility of its replenishment, rewriting and transfer to other terminals. Opportunity is very similar to the modern computerized workplace, is not it? However, the Vannevar Bush machine, which he called the Memex, was completely analog. (perhaps the word “mechanical” will be clearer, although it is not quite right)

Memex was a desk with projector screens to display information. To control the machine used the keyboard, as well as additional buttons and levers. All information was stored on microfilm, access to which was carried out using a special mechanism by a command from the keyboard. Memex was also equipped with a subsystem capable of using the dry photo process to record on microfilm new data and create new text documents.

However, the main feature of the machine was not how to store information, but how to access it. Bush suggested that special notes be written in the margin of the document, which could be used to switch between certain documents. In fact, it was a cross-reference system, a prototype of the modern hypertext.

Memex was never built, but the ideas embodied in it twenty years later received an unexpected development.

«Memex - - »

"Mongolian utopia"

The term "hypertext" was first proposed by the scientist Ted Nelson (Theodor Holm Nelson) in 1965 to refer to "text branching out or performing actions upon request." The most vividly the meaning of the idea is characterized by modern hyperlinks. When a certain keyword or concept (link) is encountered in a text for a specific query (for example, by clicking the mouse), a new document is logically linked logically to the activated link. This allows you to quickly move between documents, quickly getting all the necessary information for work.

Such a system was laid in the memex car of the Wanver Bush, but due to technical limitations, it was never implemented.

Ted Nelson, already relying on the emerging electronic computers, developed this idea, as a result of which the concept of "hypertext" appeared. However, another project, Xanadu, brought him worldwide fame and a place in the history of computing technology. The idea, unfortunately, is practically unrealizable, but it is no less beautiful.

So, Xanadu is a project of a global repository of information hosted in near-earth orbit. With the help of microfilming technologies, it was supposed to create the most complete archive of the entire written, artistic, and technical culture of mankind. Books, drawings, textbooks, works of art and other media recorded on microfilms were located on geostationary satellites capable of exchanging information with each other and with terminals on the ground over the radio channel. The archive could also be replenished with microfilm recorders and a certain stock of blank media located on satellites. In addition, Xanadu was the first hypertext project. That is, in addition to, in general, the revolutionary idea of storing information, he was also a pioneer in the implementation of new ways to search for it.

Most likely, Nelson himself was well aware of the unrealizability of such a project, but he believed (and, by the way, continues to believe so far) that with time he will be implemented.

There was another idea in the Xanadu project. Maybe not as obvious as its technical novelty, but no less important. The project was born in the 60s of the twentieth century, at the very height of the Cold War, when the world was sometimes separated from a nuclear catastrophe in a matter of hours. The 1962 Caribbean crisis alone is worth something.

In the event of a global nuclear war, mankind, perhaps, will survive. But it will inevitably be thrown back hundreds of years ago. Thousands of documents, scientific papers, technologies and works of art will disappear forever. But the storages on the geostationary Xanadu satellites will survive. With their help, humanity could quickly recover the most valuable information after such a catastrophe.

Xanadu – , , « »."Who owns the information - he owns the world"

Libraries, for several thousand years, have been the most powerful centers of education, as well as the storage, creation and use of information resources. , . , . , , , , .

. , . , , : , , , , … , .

«, , . , , . , , , »

MobiSource: https://habr.com/ru/post/78799/

All Articles