About the diacritical marks

Translation of an interesting article On diacritics (David Březina) from the blog I love typography .

The problem of diacritical marks used in central Europe is not very relevant for most of us (with their lines and dots over “Y” and “E”, it would seem to understand properly), but for designers working with foreign customers, it will be very informative . And in general, as they say, for common development ...

Concerning mistakes and other things - scold the translator (I mean, me). But not much. I write and translate as I can :)

')

Published with permission of the author.

The globalization of the typographic market and the increasing interest in creating multilingual font design is a source of great optimism among designers and printers. But, despite the widespread use of beautiful new fonts, many still do not support a number of European languages (only a separate song about Cyrillic fonts is a separate song - approx. Transl.) And only a few support African and Asian languages. It turns out the classic contradiction between the advertising statements of the creators and actually supported languages.

The purpose of this article is to explain the main features of the use and design of Latin diacritical marks, to help designers make a more informed choice in their use. The article uses diacritical marks used in central Europe for several reasons:

1) they are not very well known to western designers. The Czech printer Tomáš Brousil said: "For Western designers, our diacritics are as alien as the Arabic inscriptions." The fact that they see these signs only as a supplement for familiar Latin letters often leads to an underestimation of their importance;

2) they are well known to the author of the article;

3) many Central European languages and Czech in particular, among the first, began to use diacritical marks for Latin letters (the idea of replacing digraphs with diacritical marks was proposed by Jan Hus in his “De Ortographia Bohemica” in 1412).

Vocalization in Arabic

At different times, characters drawn to the letters or located nearby were used in many different recording systems. The Greeks used them to vividly express tonality (Greek politonics), Arabs and Jews - to denote vowel sounds. In some Indian syllabic scripts, they were used to change the sound of a syllable (that is, the original vowel sound of this syllable was changed).

In the Latin alphabet, diacritical marks are most often a tool for expanding the main alphabet for use in a particular language. This is done to represent compound letters (graphemes) or to designate sounds (phonemes) of a particular language, in cases where it is impossible to compose them from the letters of the main alphabet or such a replacement is cumbersome (try writing the Russian letter “u” in Latin. Somehow long it turns out - approx. transl.) . Roughly speaking, diacriticism is used when the main Latin alphabet ends in letters or it is required to show specific behavior (for example, to convey softness, length, stress, etc.).

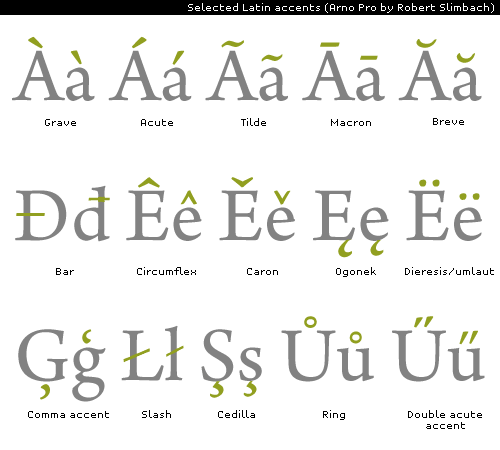

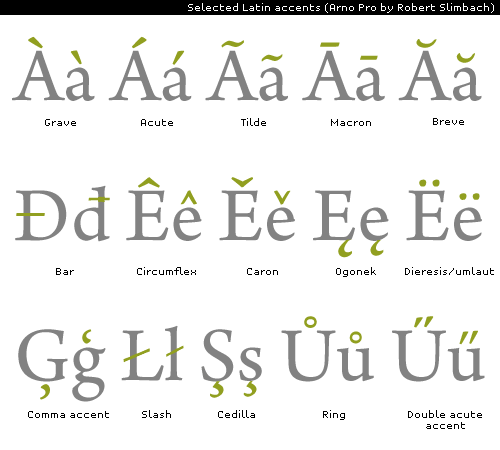

Some Latin diacritics (pdf-click-through version)

Actually, diacritics are far from the only way to expand the recording system. You can come up with new letters (for example, ß (etsect) in German), create clusters of letters (digraphs, trigraphs), as is done in some languages (for example, Welsh ) (a closer example for us: the letters "J" and "Dz" in the Belarusian language - approx. Transl.) .

Nowadays, diacritics are used in most European languages (a good “Beyond ASCII” poster on a topic on the FontShop site). An extended version of the Latin alphabet is used in several countries in Africa, in Vietnam. A large number of diacritical marks are used in transliteration (for example, Pinyin for Chinese). Another well-known extension of the Latin alphabet is the international phonetic alphabet (IPA).

Very often (but not always) letters with diacritics are full-fledged members of the national alphabet. For example, in Danish, the alphabet consists of “a – z, æ, ø, å”. The letters with diacritics are composite: they contain a symbol and a diacritical mark. Those. diacritical marks are the same integral parts of the letter as the main strokes and half-poles. And although very often diacritical marks are separated from the main letter, this does not make them less important or the element of punctuation.

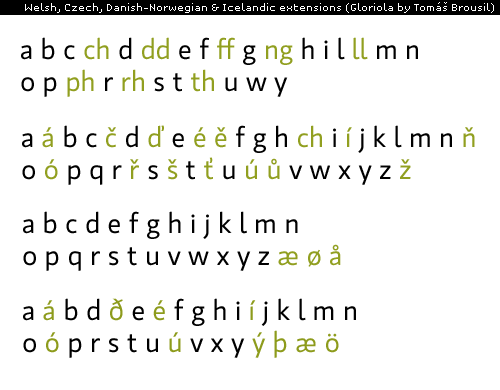

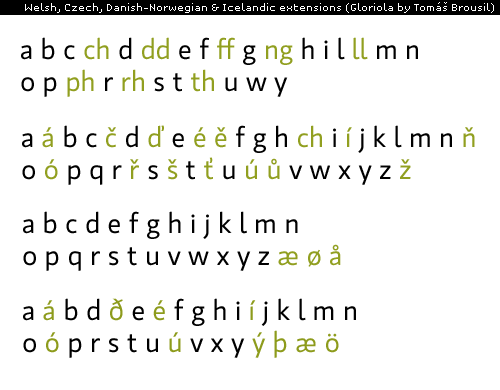

Welsh, Czech, Danish-Norwegian and Icelandic language extensions.

The last statement is very abstract and worth explaining. Punctuation is a way of separating and structuring sentences. The style of punctuation may differ (and often necessarily differs) from the stylistic principles of the construction of letters. But diacritical marks must be in harmony with the letters to which they relate, since their task, together with letters, is to convey the meaning or sound of individual words.

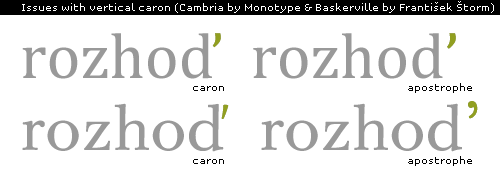

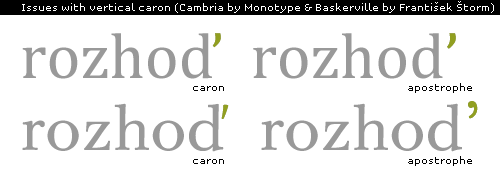

This can be illustrated by the example of an alternative caron. In the Czech and Slovak languages, Karon has a special vertical shape for use in tall letters (ď, ť, ľ, Ľ). There is no doubt that his appearance is a solution to the problem of limited space vertically on a metal letter. Ordinary caron (ě, š, č, ň, ...) cannot be placed above tall letters, so its alternative form is placed next to the letter. Very often it is mistakenly called a sign that looks like an apostrophe or even an apostrophe. But alternative caron is not an apostrophe, although their external similarity can be confusing. The Czech word “rozhoď” (d with caron) is an imperative form of the verb “scatter”, and the word “rozhod '” (the apostrophe at the end of the word) means “[he] decided” in informal writing, which is also common in literature. (I can’t vouch for the exact translation of both words, because it translates from English, there may be an effect of a “damaged phone.” However, I think the idea is clear: a different sign means a different meaning. Approx. Transl.)

The problem of the possible misreading of the text forces designers to find different ways for the visual separation of caron and apostrophe. The solution used by most modern designers is based on the closest possible arrangement of the accented character with a letter (see for example the font Greta (Peter Biľak) or the fonts from František Štorm ). Caron is designed as a simple vertical wedge, while the apostrophe is larger and retains its comma-like shape. This is how the problem between letters and punctuation is solved.

Nuances of vertical caron.

In the early days of the development of computers and the Internet, there were problems with the encoding of letters in the non-Latin alphabet, and many used to ignore diacritics in letters, chat rooms, etc. But this does not mean that the diacritical marks have lost their relevance and their use is not necessarily in modern design. They are still required in the design of the text and to achieve maximum readability.

The problem of diacritical marks is that it is unclear how a designer, who is not very familiar with this language, should evaluate the result. It is also worth noting that for the same signs the expected result may differ depending on the language or geographic region. Modern large font makers create almost identical sets of accents for all created fonts. This doubtful in-line production leads to design errors and further confuses the situation. On the other hand, there are traditional rules for creating correct diacritical marks. Such a diacritic provides better readability of the text and aesthetic appeal for native speakers. The nuances discussed below will help designers determine the correct design of diacritical marks.

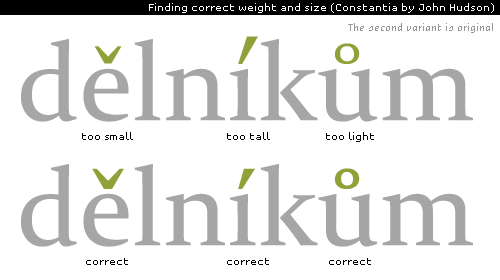

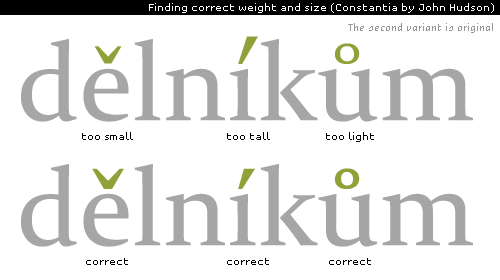

Looking for the right saturation and size. (pdf-version on click)

As mentioned above, diacritical marks are included in the letter. Therefore, they should not stand out (be lighter or darker) from the letter itself. Moreover, letters with and without diacritics have the same semantic importance; therefore, the importance of a diacritical mark should not be reduced by reducing its size. This becomes even more important for small font sizes of 10–12 pt. Typewriters often evaluate accented characters on large sizes, not paying attention to their quality with smaller ones used in the main text. The smaller the font, the greater must be the accent in comparison with the main letter.

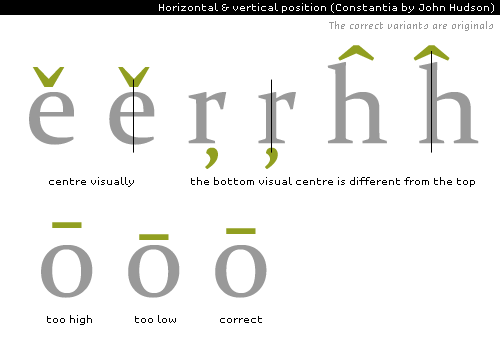

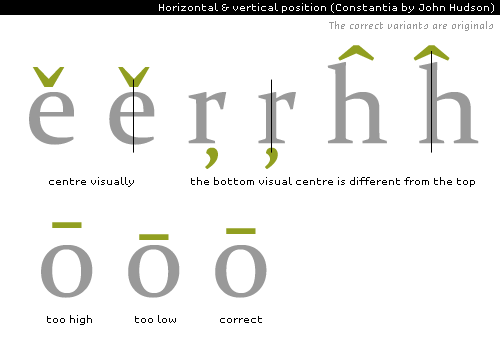

Horizontal and vertical positioning.

The arrangement of the diacritical mark is very important, since the sign must refer to the correct letter when reading. Many signs are located in the visual center above or below the letter. However, there are a number of exceptions when the accenter is located to the right of the letter (for example, the light in the letters -a, e, u-) or behind the letter (alternative caron mentioned above). Correct positioning of closely spaced signs is important, but in practice it can become a big problem. The result can vary greatly when resizing or using italics. In addition, different designers have different opinions about positioning. The general rule is simple: diacritical marks should not “fall out” of the base letter. They must also be visually attached to it.

The light

Saturation and positioning, of course, are more important than harmony of style. But, nevertheless, it should not be underestimated. In practice, diacritical marks should be in some contrast with the base letter. Font designers, often outdated, use the same contrast and tension axes as they do for ordinary letters. But, diacritical marks are not small letters, so an increased contrast in such signs as an acute, gravel, or caron may emphasize it too much relative to the base letter.

Accent marks style

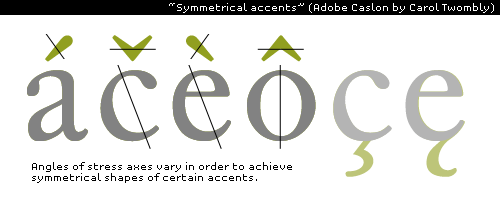

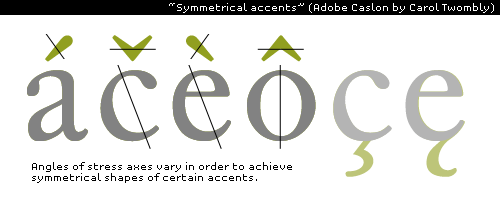

To achieve high definition and expressiveness of forms, designers often use the so-called “symmetrical diacritics” in their fonts (see the figure below). In this way, a good balance of stylistic unity and readability is achieved. The stress axes in such diacritical marks are different, but they have one goal: the creation of symmetrical shapes. Creating and positioning asymmetric diacritics is already for masters. Such a diacritic looks good in fonts based on calligraphic writing with a wide brush (here the author refers to the example above, written by Robert Slimbach, but I haven’t found this in the original - note translator) .

"Symmetric diacritics"

It is recommended to reduce the contrast between thick and thin accented lines, since they are smaller in letters and thin parts become excessively thin, weak. Other principles are also worth mentioning: the style of the ends of strokes should be the same as in letters. More refined options (such as serifs, semicircular endings, etc.) are usually not used in diacritics.

If an open letter clearance is used in the font, diacritical marks (cedi, light) should also look similar.

Since space is very limited above capital letters, special diacritical marks should be used for them. They are smaller, lower and better combined with the capital letters. Some designers additionally create diacritics for more and capitals. This is highly recommended if the style of capital letters (including capitals) and lowercase letters is significantly different. In cases of minor differences, the diacritics used in lowercase letters are also used for capitals.

Last but not least, the accents should not be overly similar. Too flat accent "´" can easily be confused with the macron "¯". Too rounded caron “ˇ” is easily confused with the log “˘”. It is for this reason that when creating diacritical marks, it is not worthwhile to move far from the original generally accepted forms.

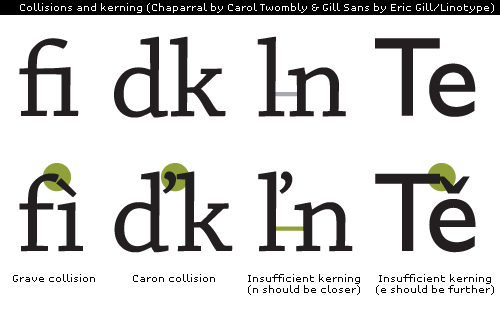

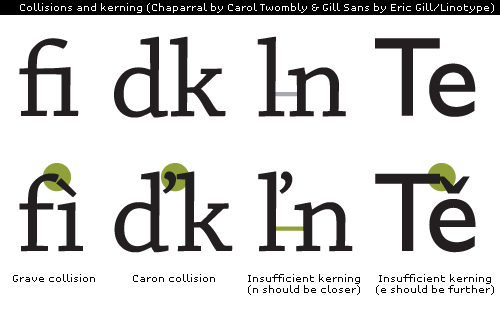

Diacritical marks should not be in contact, and layered, create illegible shapes. Therefore, a neat fit is often required. No single font designer can predict and take into account all possible combinations of accents, so it is recommended that you customize the letters in your opinion and taste.

Collisions and kerning. (pdf-version on click)

Most of the problems when working with diacritics are left out of this introductory article. But from the above, it should be clear that the diacritical marks are not just an addition to the letters of the main alphabet. They form letters.

The images provided here emphasize those fonts that, for obvious reasons, have higher requirements. Careful study and understanding of the purpose, aesthetics will help designers choose fonts with well-developed diacritics (or at least be aware of the lack of something). This increases the quality of texts in their native languages.

The problem of diacritical marks used in central Europe is not very relevant for most of us (with their lines and dots over “Y” and “E”, it would seem to understand properly), but for designers working with foreign customers, it will be very informative . And in general, as they say, for common development ...

Concerning mistakes and other things - scold the translator (I mean, me). But not much. I write and translate as I can :)

')

Published with permission of the author.

The globalization of the typographic market and the increasing interest in creating multilingual font design is a source of great optimism among designers and printers. But, despite the widespread use of beautiful new fonts, many still do not support a number of European languages (only a separate song about Cyrillic fonts is a separate song - approx. Transl.) And only a few support African and Asian languages. It turns out the classic contradiction between the advertising statements of the creators and actually supported languages.

The purpose of this article is to explain the main features of the use and design of Latin diacritical marks, to help designers make a more informed choice in their use. The article uses diacritical marks used in central Europe for several reasons:

1) they are not very well known to western designers. The Czech printer Tomáš Brousil said: "For Western designers, our diacritics are as alien as the Arabic inscriptions." The fact that they see these signs only as a supplement for familiar Latin letters often leads to an underestimation of their importance;

2) they are well known to the author of the article;

3) many Central European languages and Czech in particular, among the first, began to use diacritical marks for Latin letters (the idea of replacing digraphs with diacritical marks was proposed by Jan Hus in his “De Ortographia Bohemica” in 1412).

Vocalization in Arabic

At different times, characters drawn to the letters or located nearby were used in many different recording systems. The Greeks used them to vividly express tonality (Greek politonics), Arabs and Jews - to denote vowel sounds. In some Indian syllabic scripts, they were used to change the sound of a syllable (that is, the original vowel sound of this syllable was changed).

In the Latin alphabet, diacritical marks are most often a tool for expanding the main alphabet for use in a particular language. This is done to represent compound letters (graphemes) or to designate sounds (phonemes) of a particular language, in cases where it is impossible to compose them from the letters of the main alphabet or such a replacement is cumbersome (try writing the Russian letter “u” in Latin. Somehow long it turns out - approx. transl.) . Roughly speaking, diacriticism is used when the main Latin alphabet ends in letters or it is required to show specific behavior (for example, to convey softness, length, stress, etc.).

Some Latin diacritics (pdf-click-through version)

Actually, diacritics are far from the only way to expand the recording system. You can come up with new letters (for example, ß (etsect) in German), create clusters of letters (digraphs, trigraphs), as is done in some languages (for example, Welsh ) (a closer example for us: the letters "J" and "Dz" in the Belarusian language - approx. Transl.) .

Nowadays, diacritics are used in most European languages (a good “Beyond ASCII” poster on a topic on the FontShop site). An extended version of the Latin alphabet is used in several countries in Africa, in Vietnam. A large number of diacritical marks are used in transliteration (for example, Pinyin for Chinese). Another well-known extension of the Latin alphabet is the international phonetic alphabet (IPA).

Use of diacritics

Very often (but not always) letters with diacritics are full-fledged members of the national alphabet. For example, in Danish, the alphabet consists of “a – z, æ, ø, å”. The letters with diacritics are composite: they contain a symbol and a diacritical mark. Those. diacritical marks are the same integral parts of the letter as the main strokes and half-poles. And although very often diacritical marks are separated from the main letter, this does not make them less important or the element of punctuation.

Welsh, Czech, Danish-Norwegian and Icelandic language extensions.

The last statement is very abstract and worth explaining. Punctuation is a way of separating and structuring sentences. The style of punctuation may differ (and often necessarily differs) from the stylistic principles of the construction of letters. But diacritical marks must be in harmony with the letters to which they relate, since their task, together with letters, is to convey the meaning or sound of individual words.

This can be illustrated by the example of an alternative caron. In the Czech and Slovak languages, Karon has a special vertical shape for use in tall letters (ď, ť, ľ, Ľ). There is no doubt that his appearance is a solution to the problem of limited space vertically on a metal letter. Ordinary caron (ě, š, č, ň, ...) cannot be placed above tall letters, so its alternative form is placed next to the letter. Very often it is mistakenly called a sign that looks like an apostrophe or even an apostrophe. But alternative caron is not an apostrophe, although their external similarity can be confusing. The Czech word “rozhoď” (d with caron) is an imperative form of the verb “scatter”, and the word “rozhod '” (the apostrophe at the end of the word) means “[he] decided” in informal writing, which is also common in literature. (I can’t vouch for the exact translation of both words, because it translates from English, there may be an effect of a “damaged phone.” However, I think the idea is clear: a different sign means a different meaning. Approx. Transl.)

The problem of the possible misreading of the text forces designers to find different ways for the visual separation of caron and apostrophe. The solution used by most modern designers is based on the closest possible arrangement of the accented character with a letter (see for example the font Greta (Peter Biľak) or the fonts from František Štorm ). Caron is designed as a simple vertical wedge, while the apostrophe is larger and retains its comma-like shape. This is how the problem between letters and punctuation is solved.

Nuances of vertical caron.

In the early days of the development of computers and the Internet, there were problems with the encoding of letters in the non-Latin alphabet, and many used to ignore diacritics in letters, chat rooms, etc. But this does not mean that the diacritical marks have lost their relevance and their use is not necessarily in modern design. They are still required in the design of the text and to achieve maximum readability.

Accent marks design

The problem of diacritical marks is that it is unclear how a designer, who is not very familiar with this language, should evaluate the result. It is also worth noting that for the same signs the expected result may differ depending on the language or geographic region. Modern large font makers create almost identical sets of accents for all created fonts. This doubtful in-line production leads to design errors and further confuses the situation. On the other hand, there are traditional rules for creating correct diacritical marks. Such a diacritic provides better readability of the text and aesthetic appeal for native speakers. The nuances discussed below will help designers determine the correct design of diacritical marks.

1. Saturation and size

Looking for the right saturation and size. (pdf-version on click)

As mentioned above, diacritical marks are included in the letter. Therefore, they should not stand out (be lighter or darker) from the letter itself. Moreover, letters with and without diacritics have the same semantic importance; therefore, the importance of a diacritical mark should not be reduced by reducing its size. This becomes even more important for small font sizes of 10–12 pt. Typewriters often evaluate accented characters on large sizes, not paying attention to their quality with smaller ones used in the main text. The smaller the font, the greater must be the accent in comparison with the main letter.

2. Positioning

Horizontal and vertical positioning.

The arrangement of the diacritical mark is very important, since the sign must refer to the correct letter when reading. Many signs are located in the visual center above or below the letter. However, there are a number of exceptions when the accenter is located to the right of the letter (for example, the light in the letters -a, e, u-) or behind the letter (alternative caron mentioned above). Correct positioning of closely spaced signs is important, but in practice it can become a big problem. The result can vary greatly when resizing or using italics. In addition, different designers have different opinions about positioning. The general rule is simple: diacritical marks should not “fall out” of the base letter. They must also be visually attached to it.

The light

3. Harmony of style

Saturation and positioning, of course, are more important than harmony of style. But, nevertheless, it should not be underestimated. In practice, diacritical marks should be in some contrast with the base letter. Font designers, often outdated, use the same contrast and tension axes as they do for ordinary letters. But, diacritical marks are not small letters, so an increased contrast in such signs as an acute, gravel, or caron may emphasize it too much relative to the base letter.

Accent marks style

To achieve high definition and expressiveness of forms, designers often use the so-called “symmetrical diacritics” in their fonts (see the figure below). In this way, a good balance of stylistic unity and readability is achieved. The stress axes in such diacritical marks are different, but they have one goal: the creation of symmetrical shapes. Creating and positioning asymmetric diacritics is already for masters. Such a diacritic looks good in fonts based on calligraphic writing with a wide brush (here the author refers to the example above, written by Robert Slimbach, but I haven’t found this in the original - note translator) .

"Symmetric diacritics"

It is recommended to reduce the contrast between thick and thin accented lines, since they are smaller in letters and thin parts become excessively thin, weak. Other principles are also worth mentioning: the style of the ends of strokes should be the same as in letters. More refined options (such as serifs, semicircular endings, etc.) are usually not used in diacritics.

If an open letter clearance is used in the font, diacritical marks (cedi, light) should also look similar.

Since space is very limited above capital letters, special diacritical marks should be used for them. They are smaller, lower and better combined with the capital letters. Some designers additionally create diacritics for more and capitals. This is highly recommended if the style of capital letters (including capitals) and lowercase letters is significantly different. In cases of minor differences, the diacritics used in lowercase letters are also used for capitals.

Last but not least, the accents should not be overly similar. Too flat accent "´" can easily be confused with the macron "¯". Too rounded caron “ˇ” is easily confused with the log “˘”. It is for this reason that when creating diacritical marks, it is not worthwhile to move far from the original generally accepted forms.

4. Fit and kerning

Diacritical marks should not be in contact, and layered, create illegible shapes. Therefore, a neat fit is often required. No single font designer can predict and take into account all possible combinations of accents, so it is recommended that you customize the letters in your opinion and taste.

Collisions and kerning. (pdf-version on click)

Conclusion

Most of the problems when working with diacritics are left out of this introductory article. But from the above, it should be clear that the diacritical marks are not just an addition to the letters of the main alphabet. They form letters.

The images provided here emphasize those fonts that, for obvious reasons, have higher requirements. Careful study and understanding of the purpose, aesthetics will help designers choose fonts with well-developed diacritics (or at least be aware of the lack of something). This increases the quality of texts in their native languages.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/52258/

All Articles