JavaScript lexical scope and closure

JavaScript environment translation , Lexical Scope and Closures .

Let's talk about the environment. Our huge planet is one for all. When building a new chemical plant, it would be nice to isolate it so that all internal processes do not leave its borders. We can say that the environment and microclimate of this plant are isolated from the external environment.

')

The program is similarly arranged. What you create externally — external functions, conditional statements, loops, and other blocks — is an external, global environment.

The constant

age , the multiplier function, and the result variable are in the external environment. These components have a global scope. A scope is the area in which a component is available.In this case,

x is a constant inside the multiplier function. Since it is inside a block of code, it is a local constant, not a global one. It is visible only inside the function, but not outside - its scope is local.The

multiplier function has another component from the local scope - this is the num argument. It is more difficult to define it than a constant or a variable, but it behaves approximately like a local variable.We do not have external access to

x - it does not seem to exist:

console.log called x in a global environment in which it is not defined. As a result, we got a ReferenceError.We can set

x globally:

We have a global

x with a known value, but the local x in the multiplier function is still visible only from the inside. These x are not connected in any way - they are in different environments. Despite the same name, they do not mix.Any block of code in braces becomes the local environment. Here is an example using

if :

The same thing happens with

while and for loops.So local means invisible from the outside. That is, global is visible everywhere, even inside objects? Yes!

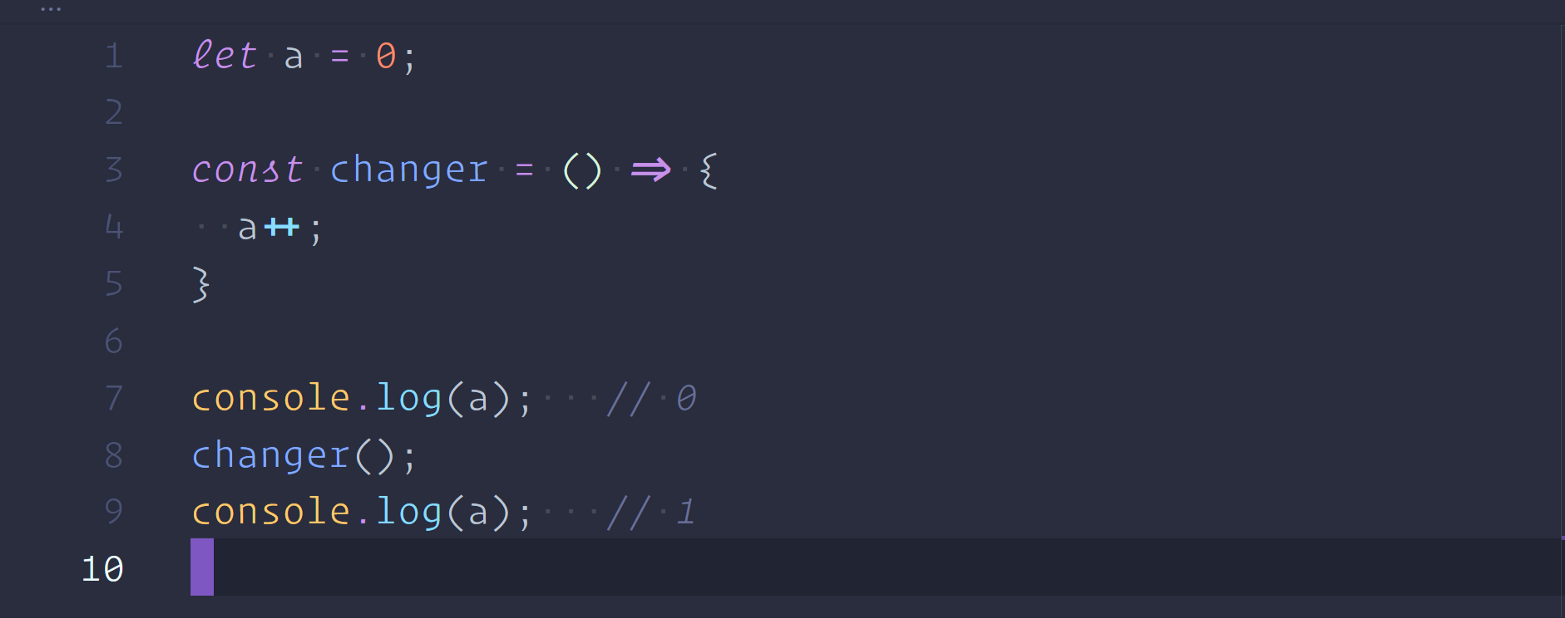

The global variable

a has changed inside the changer function. The function takes effect only when called, not when defined, therefore initially a=0 , and when called, changer takes the value 1 .It's easy to succumb to the temptation and put everything in a global scope, forgetting about all the complexities of individual environments - but this is a terrible idea. Global variables make your code extremely fragile, any element can break any other at any time. Therefore, do not use the global scope and keep everything in place.

Part II. Lexical scope

Take a look at this program:

The

multiplier function returns the results of a and b . a given inside, but b not.When trying to perform the

a*b multiplication operation, JavaScript looks for the values of a and b . He begins to search inside, and then goes outside, studying one area after another, until he finds what he was looking for, or does not understand that it is impossible to find.Therefore, in this example, JavaScript starts looking for

a inside the local area - inside the multiplier function. He immediately finds the value and goes to b . b he will not find in the local environment, so he goes beyond it. There he learns that b is 10 . So a*b turns into 5*10 , and then to 50 .This piece of code could be inside another function, which is also inside another function. Without finding

b in the first layer, JavaScript would continue to search everything in new and new layers, further and further.Note that

a=7 does not affect the calculation result in any way: the value of a was found inside, therefore, the external a does not play a role.This is called the lexical scope. The scope of any component is determined by the location of this component in the code, and nested blocks have access to external areas.

Part III. Short circuits

Environments and scopes are supported by most programming languages, and this mechanism allows the introduction of closures. Closure is inherently a function that “remembers” external entities used internally.

Before continuing, let's recall how functions are created and used:

f is a pretty useless function that always returns 0 . The set consists of two parts - a constant and the function itself.It is important to remember that these are separate components. The first component is a constant called

f . Its value can be a number or a string value. In this case, the value is a function.In past lessons, we cited an analogy: constants are like sheets of paper with a name on one side and a value on the other. Thus,

f is a piece of paper with f written on one side and a description of the function being launched on the other.When calling this function:

A new “box” is created based on the description from a sheet of paper.

Back to the closures. Here is a sample code.

The

createPrinter function creates a name constant, and then a function called printName . Both are local to the createPrinter function and are available only inside it.printName itself has printName local components, but there is access to the scope where it is created, and to the external environment, where the constant is assigned a name .The

createPrinter function returns the printName function. Recall that function definitions are descriptions of running functions; they are simply data elements, like numbers or chains. Therefore, we can return the definition of a function in the same way as we return numbers.In the outer scope, we create the constant

myPrinter and set the return value to it as createPrinter . A function is returned, so myPrinter also becomes a function. When you call it, King will appear on the screen.Here's the funny thing: the

name constant was created inside the createPrinter function. The function was called and executed. As you know, when a function finishes working, it ceases to exist. The magic box disappears along with all the contents.But he returned another function that somehow remembered the

name constant. Thus, when calling myPrinter we get King - the value that the function remembers, despite the fact that this area no longer exists.The function that

createPrinter returns is called a closure. A closure is a combination of a function and the environment in which it was defined. The function "enclosed" in itself certain information received in the scope.This may seem like a weird quirk of JavaScript, but using closures wisely can help make your code nicer, cleaner, and more readable. The very principle of returning functions, like returning numbers and string values, gives you more freedom to maneuver.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/460861/

All Articles