A few stories from the life of the JSOC CERT, or nonbanal forsenika

We are investigating incidents at JSOC CERT. In general, all 170 people in JSOC are investigating, but the most technologically complex cases fall into the hands of CERT experts. How, for example, to detect traces of malware, if the attacker cleaned up after himself? How to find the "wizard" who deleted important business documents from a file server, which is not really configured logging? And for the sweet: how can an attacker, without penetrating the network, get passwords from dozens of unrelated domain uchetok? Details, as always, under the cut.

JSOC CERT weekdays

Often we have to evaluate the actual compromise of the customer network, for this we carry out:

- Retrospective analysis of hard drives and memory images

- malware reverse engineering,

- if necessary, emergency deployment of monitoring and scanning of hosts for the presence of indicators of compromise and traces of hacking.

In our free time, we write detailed notes, techniques, and playbooks — essentially instructions that help scale up even complex investigations, since you can act on them semi-automatically.

')

Sometimes during the response to an incident - right in the middle of extinguishing a “fire” - one also has to act as a “psychological support service”. Once we were invited to help with counteracting the infection of the subnet of a large organization. The network was served by two contractors who, in this situation, selflessly

During the investigation, we often have to pick disk and memory images to find active malware there. For the process to be predictable and objective, we formalized and automated several techniques for the retrospective analysis of disks, and took the already classic SANS method as a basis - in the original version it is quite high-level, but if properly used, it can detect active infection with very high accuracy.

It is clear that all-all checks require time and deep expert knowledge about the features of the various components of operating systems (and specialized software is needed a lot).

How to simplify the disk check for an active infection? We share life hacking - it can be checked dynamically (as in a sandbox), for this:

- copy the hard disk of the suspicious host bit by bit;

- convert the resulting dd image to VMDK format using this utility;

- Run the VMDK image in Virtual Box / VMware;

- and analyze as a live system, paying attention to traffic.

But there will always be incidents for which detailed instructions are not written and techniques are not automated.

Case 1. Accountant to do with it, or How were we looking for the malware?

A client asked us to check the accountant’s computer for malware: someone had sent several payment orders to an unknown address. The accountant argued that he was not involved in this and that the computer had previously behaved strangely: the mouse sometimes literally moved on the screen itself - in fact, we were asked to check these readings. The snag was that the Trojan aimed at 1C did its dirty work and removed itself, and almost a month passed after infection - during this time the diligent enikeyschik put up a lot of software, chafing the unallocated disk space and thereby minimizing the likelihood of success in the investigation.

In such cases, only an experienced analyst who is picky to details and an extensive, automatically updated Threat Intelligence database can help. So, during the scan of the startup folder, attention was drawn to a suspicious label indicating an alleged anti-virus update utility:

Unfortunately, the Trojan’s carcass was not recovered from the disk, but the Superfetch cache was full of facts about the launch of the remote administration utility from the same folder:

Comparing them with the time of the incident, we proved that it was not the accountant who was guilty of stealing money, but an external intruder.

Case 2. Who deleted my files?

Most of our investigations and incident responses are in one way or another connected with malware detection, targeted attacks using multi-module utilities, and similar stories with an external attacker. However, sometimes there are much more mundane, but no less interesting investigations.

The client had the most common old file server, the shared folders of which were accessible to several departments. On the server there were a lot of very important business documents that someone took and deleted. They realized it was late - after the backup was reset. Began to look for the guilty.

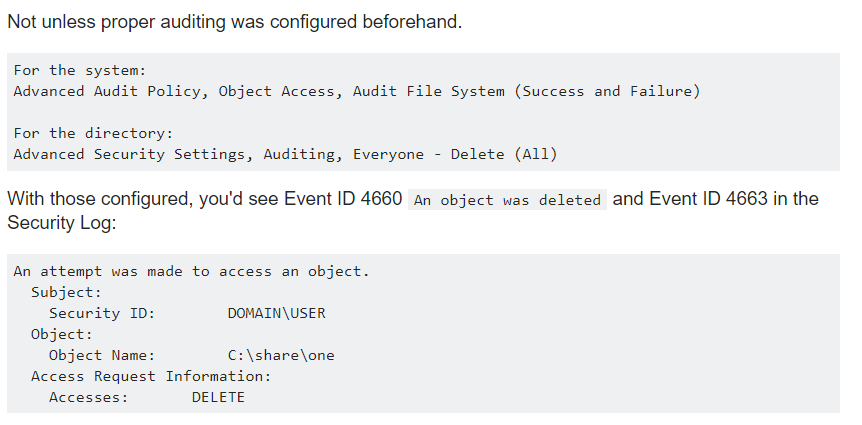

If you ever google how to determine which user deleted a file, you probably came across tips that boil down to the fact that everything is in the Windows logs, if you tried to configure them in advance (by the way, we already gave a couple of tips customize logs):

A source

But in reality, few people conduct an audit of the file system, trite because there are many file operations and logs will be quickly rewritten, and a separate server is needed to store logs ...

We decided to break the task set into two: first, to determine when the files were deleted; secondly, - the KTO was connected to the server at the moment of deletion. If you have an idea about the features of NTFS, then you know that in most implementations of this file system, when you delete a file, the space that it occupied is marked as free, and its time stamps do not change. Therefore, at first glance, the removal time can not be set.

However, in the file system there are not only files, but also folders. At the same time, folders have a special attribute $ INDEX_ROOT, which describes the contents of the folder as a B-tree. Naturally, deleting a file changes the attribute $ INDEX_ROOT of the folder and thereby changes its timestamps, in particular, in the $ STD_INFO structure. Thus, it is possible to determine the approximate time of deleting a large number of files and folders by anomaly in the MFT (main file table) :

Having found out when the files were approximately deleted, you can try to find out who was working in the north at this point in order to narrow the circle of suspects. The following methods come to mind:

- according to the logs of the server itself - by the events with EventID 4624/4625 you can see when the user has connected and disconnected;

- by domain controller logs - EventID 4768 allows you to determine that a particular user requested access to the server;

- for traffic — netflow / logs of internal routers — you can figure out who actively communicated over the network with this server via smb.

In our case, this data was no longer there: too much time passed, the logs were rotated. In this case, there is another not very reliable, but still method, but rather the registry key - Shellbags . It stores information, in particular, about what kind of folder the folder had when the user visited it last: table, list, large icons, small icons, contents, etc. And the same key contains time stamps, which can be interpreted with a high degree of confidence as the time of the last visit to the folder.

The method was found, the case remains for small - to collect registries from the necessary hosts and analyze them. For this you need:

- determine by the domain group who had access to the folder (in our case there were about 300 users);

- collect registries from all the hosts on which these users worked (you just can't do it, you need a special utility to work with the disk directly, for example, https://github.com/jschicht/RawCopy );

- Feed all registries in Autopsy and use the Shellbags plugin;

- Profit!

Specifically, in this incident, the time for deleting files coincided with the time of visiting the root of the deleted folder by one of the users, which allowed us to narrow the circle of suspects from 300 people to 1.

What happened next with this employee - history is silent. We only know that the girl confessed that she did it by chance, and continues to work in the company.

Case 3. Password cases master: “hijack” in a couple of seconds (and even faster)

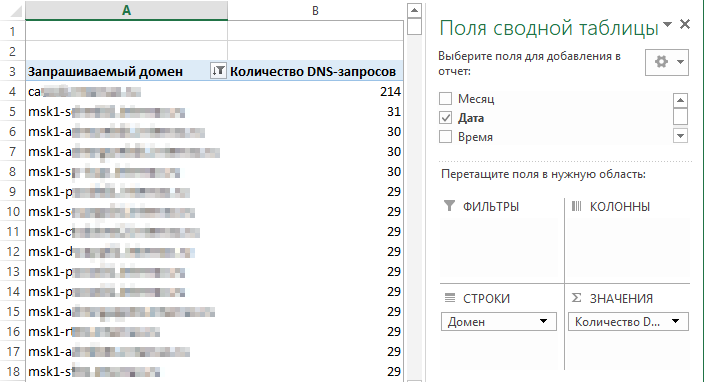

The attacker entered the network of the client who asked us for help through the VPN and was immediately detected. Which is not surprising, because immediately after entering it, he began scanning the subnet with a vulnerability scanner - the hanipot began to blink like a Christmas tree.

After the account was locked, the client’s security staff began to parse the VPN logs and saw that the intruder used more than 20 different domain records to penetrate (with the majority he successfully logged in, and for some the authentication failed). And a logical question arose: how did he learn passwords from these accounts? Our guys from JSOC CERT were invited to search for the answer.

In one of the previous articles, we have already said that in investigations, hypotheses should be formed and tested as their probability decreases. So we did this time, starting to describe the typical vectors of account theft:

- external service data leak

- Bruteforce

- Mimikatz or similar technology

- Keylogger

- Phishing

- NTLM-hash harvesting (for example, https://github.com/CylanceSPEAR/SMBTrap ) or similar network attacks.

Checked a bunch of versions, but nowhere was there even a hint of an attack. Not that the investigation is deadlocked, but an inner voice and common sense suggested: something is wrong here - you need to take a step back and look at the picture wider.

Indeed, at first glance, all these accounts are not related to each other. Their owners are from different, geographically separated departments. Usually use a non-overlapping set of company services. Even the level of IT literacy is different. Yes, one step back was not enough - one more was needed.

By this time we managed to collect a huge number of logs from different systems of the enterprise and highlight the traces left by the attacker. We began to analyze where he lit up (remember: he actively scanned the company's internal network). We noticed that against the background of a uniformly distributed network noise from scattering exploits, there is an abnormally large number of requests to the password recovery service. A service accessible from the Internet. Hmm ...

If you are monitoring security events, you probably know that analyzing attempts to attack an externally accessible server often does not make sense due to Internet noise: in general, it’s not easy to distinguish really serious attacks from numerous script-kiddie attempts. But not always.

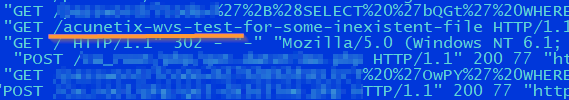

After spending some time on the web service logs, we were able to isolate the following attacks on the service:

- Acunetix Scan,

- SQLmap scanning

- A large number of requests to one page.

The third attack, at first glance, is similar to brute logging in users. But this is not so, because the service is protected from this, at least, by the fact that the passwords are stored in a salt-hashed form - or not? It was necessary to check it quickly.

The picture below shows a typical scheme of the service for resetting passwords:

It is interesting that passwords are not always stored in a protected form - there is a moment in time when they are in the public domain - immediately after the filing of the application and prior to its execution! A large number of requests to a single page turned out not to be brute force or scanning, but high-frequency queries with SQL injection, the purpose of which was to catch the passwords at the time of their change.

So, having conducted a simulation of an attack on a service, comparing information from web server logs, password change logs and several network devices, we did find the attacker's point of entry into the enterprise.

So, colleagues, dig into raw data and may the force be with you!

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/460113/

All Articles