How Qualcomm has ripped off the mobile industry for almost 20 years in a row.

Detailed analysis of a 233-page document accusing Qualcomm of monopolism

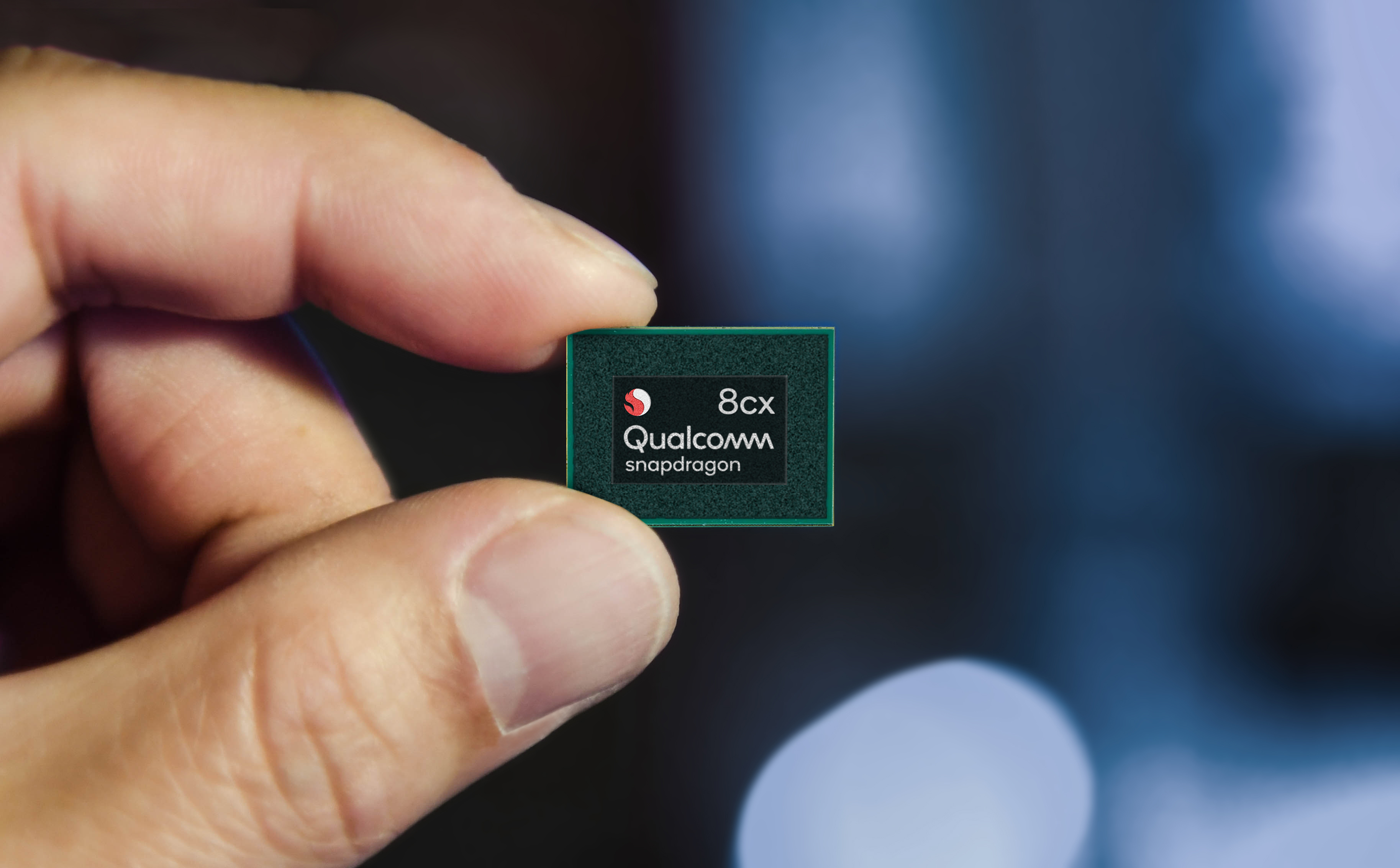

In 2005, Apple contacted Qualcomm as a potential supplier of modem chips for the iPhone. The response received from Qualcomm was unusual: in a letter, the company demanded that Apple sign a patent license agreement even before Qualcomm even considered the possibility of supplying chips.

“In the 20 years I have been working with this industry, I have never seen such letters,” said Tony Blevins, Apple's vice president of procurement.

')

Most suppliers readily communicate with new customers - especially with such large and prestigious ones as Apple. But Qualcomm was not like other suppliers; she enjoyed a dominant position in the cellular chip market. This gave the company a large lever of pressure, and she was not afraid to use it.

Blevins comments we heard this year, when he spoke before the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) in the sensational antitrust case against Qualcomm. FTC filed this lawsuit in 2017, partly under pressure from Apple, for ten years by the dominance of Qualcomm in the field of wireless chips.

Last week, a Californian federal judge provided Apple and the FTC with the desired revenge. In a stinging 233-page verdict, Judge Lucy Koch ruled that Qualcomm’s aggressive licensing tactics violate US antitrust laws.

I read the judge’s verdict entirely, although it is the size of a book - and in it Qualcomm is exposed as a merciless monopolist. This legal document describes a nearly 20-year history of overpricing cellular chips for smartphone makers. Qualcomm made its contracts with manufacturers of smartphones in such a way that it was almost impossible for other chip makers to challenge Qualcomm's dominance. Customers who did not like the one-sided working conditions with Qualcomm were frightened by the sharp loss of access to modem chips, which could cause them serious damage.

"Qualcomm had monopoly power over certain cell phone chips, and she used this power to bill people too much," said Charles Duan, an expert on patent law at the R Street Free Market Institute. "Instead of simply demanding more money for the chips themselves, they demanded to buy a patent license and took too much for it."

And now this dominance is probably coming to an end. Koch has ordered Qualcomm to stop threatening customers with cessation of chip shipments. The company is obliged to renegotiate all contracts with customers and sell the license to competitors at a reasonable price. And if Koh’s verdict survives the appeal, for the first time in this century, it can lead to the emergence of a truly competitive market for wireless chips.

Qualcomm ideal profit machine

Different cellular networks work with different wireless standards, and every few years these standards change. For almost 20 years, Qualcomm has been enjoying the position of a leader - and sometimes the use of a dead snap - in the field of chips that support basic cellular standards. So if a smartphone maker wanted to sell its products all over the world, there was practically no choice but to make a deal with Qualcomm.

For example, in the early 2010s, Qualcomm enjoyed the leading position on chips for the CDMA standard, which were preferred by Verizon and Sprint, as well as some other operators in other countries. Technology Director Qualcomm James Thompson bluntly explained in an internal correspondence with director Steve Mollenkopf, how this circumstance gave the company a lever of pressure on Apple:

“Today we are the only supplier able to provide them with a global launch,” said Thompson’s letter in court documents. “And in general, without us they will lose large parts of North America, Japan and China. And it will hit him hard. ”

And this situation arose not only with Apple. BlackBerry was in a similar situation around 2010. In his testimony, one of the BlackBerry executives, John Grubbs, said that without access to Qualcomm chips, "30% of the sales of our devices simply would not have happened if we could not have installed devices with CDMA support."

Over the past two decades, Qualcomm has entered into contracts with most of the leading manufacturers of cell phones, including LG, Sony, Samsung, Huawei, Motorola, Lenovo, ZTE and Nokia. These deals have provided Qualcomm with an incredible leverage on these companies - a lever that enabled Qualcomm to receive patent royalties that drastically outweigh similar revenues from other companies with a similar set of patents.

The cost of patent fees was calculated on the basis of the value of the entire phone, and not just the value of the chips themselves, which included the patented technology. This, in essence, meant that Qualcomm received its share for each of the many components of a smartphone, most of which had nothing to do with Qualcomm's cellular patents.

“Qualcomm is demanding more money from us than all the others put together,” said one of Apple executives, Jeff Williams. “We have never had such significant deductions related to intellectual property licenses,” said Tod Madder of Motorola.

Internal documents from Qualcomm confirmed these statements. One showed that in one of the licensing agreements in 2018, the company received $ 7.7 billion - more than the total income of 12 other companies with significant patent portfolios.

No license - no chips

These high royalties reflected an unusual bargaining tactic called “no license - no chips”. No one could buy Qualcomm's cellular chips without first signing the licensing agreement to use the Qualcomm patent portfolio. And the terms of these contracts are seriously inclined in favor of Qualcomm.

When the phone maker signed his first deal with Qualcomm, the company got even more pressure. Qualcomm had the right to unilaterally stop the supply of chips to the manufacturer after the expiration of the patent license agreement.

“If we cannot get a modem, we cannot release the device,” said Todd Madder of Motorola in testimony. "It can take months to design a replacement solution, if it exists at all in the market."

Because of this, Qualcomm customers became very vulnerable when approaching the expiration date of the patent contract. If a client tried to bargain for better terms - not to mention formal claims to Qualcomm's patent applications through the courts - the company could cut off shipments of chips to the company.

“We explained that we are thinking about the possibility of refusing to renew the license,” said Ira Bloomberg, one of the Lenovo executives, during his testimony at the trial. One of the leaders of Qualcomm "reacted very calmly to this, and said that it was our right, but in that case we could no longer purchase chips from Qualcomm."

“And these are months and months, if not years, without supplies,” said Bloomberg in his testimony. It would be “if not fatal, then almost fatally for almost any company in this business.”

Judge Koch discovered that Qualcomm used this tactic again and again in the past 20 years: Qualcomm threatened to interrupt the supply of Samsung chips in 2001, LG in 2004, Sony and ZTE in 2012, Huawei and Lenovo in 2013, Motorola in 2015.

Qualcomm chip supply contracts eliminate competitors

There is an obvious question - how could Qualcomm hold in their hands the supply of chips for modems. In particular, this was possible because Qualcomm hired talented engineers and spent billions of dollars to keep its chips the most advanced.

Qualcomm also maintained a dominant position, selling systems on a chip, which included a central processor and other functions besides modems. This yielded significant savings in cost and energy consumption, as well as complicating competition from small producers.

But besides these technical reasons, Qualcomm has built agreements with customers so that other companies find it difficult to break into the chip market for cellular modems.

Qualcomm's first weapon against competitors: among the conditions of a patent license was the requirement to deduct royalties from each phone sold - and not just from phones that contained Qualcomm wireless chips. This gave Qualcomm a particular advantage in the fight against other manufacturers. If another manufacturer tried to sell its chips for cheaper chips from Qualcomm, then it could easily afford to drop the price of its chips, knowing that the client would still pay massive patent fees from each phone.

Judge Koch drew a direct parallel with similar licensing behavior, which brought Microsoft problems in the 1990s. Microsoft offered PC makers discounts if they agreed to pay Microsoft licensing fees for the sale of each PC - regardless of whether MS-DOS was installed on it. This, in essence, meant that the PC manufacturer had to pay twice when releasing a PC that did not have Microsoft operating systems. In 1999, a federal judge ruled that a reasonable jury would have recognized a violation of such an antitrust law agreement as Microsoft made it difficult for competitors to enter the market.

And in some licensing agreements with Qualcomm, there were conditions that directly prohibited companies from using wireless chips from other suppliers. Qualcomm offered cell phone makers discounts on every Qualcomm chip they sold. However, these discounts could be obtained only if the manufacturer used chips from Qualcomm not less than 85% of the phones produced by them (and in some cases - all 100%).

For example, Apple signed an agreement with Qualcomm in 2013, according to which it guaranteed exclusive use of Qualcomm chips. Under the terms of the deal, Qualcomm paid Apple hundreds of millions of dollars in returns and marketing promotions from 2013 to 2015. However, Qualcomm could stop these payments if Apple began selling an iPhone or iPad without Qualcomm chips.

Apple would even have to pay back these payments if it didn’t use cellular chips from Qualcomm until February 2016. In one Qualcomm internal email, it was estimated that Apple would owe $ 645 million if it launched an iPhone without a Qualcomm cellular chip in 2015 m

Qualcomm has made similar deals with other major cell phone manufacturers. In 2003, Qualcomm signed a 10-year deal with Huawei, in which it promised to reduce deductions to 2.65%, provided that Huawei purchases 100% of CDMA chips for the Chinese market from Qualcomm. If Huawei would buy chips not from Qualcomm, royalties rose to 5% or more.

The deal from 2004 stipulated the return of payments to LG, if LG will buy at least 85% of CDMA chips from Qualcomm. According to the deal, LG was supposed to pay high royalties on patents when selling phones that do not contain cellular chips from Qualcomm. The deal from 2018 implied incentive payments in favor of Samsung if it would buy 100% of “premium” cellular chips from Qualcomm - as well as a certain minimum percentage of chips with a smaller status.

“It is unlikely that the market will have a sufficiently large request for autonomous modems”

Such exclusive or almost exclusive conditions were important, because for a profitable entry into the cellular modem market, enormous scales were required. It would take hundreds of millions of dollars to design a competing cellular chip from scratch. And such projects will be relevant for several years, after which they will irrevocably become obsolete.

This means that the company has a sense to enter the market only if a line of large customers has already lined up for it - customers willing and able to order millions of chips in the first year. And such orders can place a very limited number of customers.

Qualcomm executives clearly understood this. In an internal letter of 2010, Steve Mollenkopf wrote about the "significant strategic advantages" of signing an exclusive deal with Apple, since "it is unlikely that the market will have a large enough request for autonomous modems to keep a competitor afloat."

And it was not just a theoretical problem. Apple hated dependence on Qualcomm and was looking for a second source of modem chips to develop. The strongest candidate was Intel, which did not release significant amounts of modem chips, but was interested in this. By 2012, Apple had already planned to order from Intel the development of a cellular chip for the 2014 iPad.

Apple's Qualcomm deal from 2013 forced the company to bury this plan - and a larger collaboration with the Intel cellular team. Blevins testified at the trial that “they stopped the development that we had with Intel for iPad” after signing the contract. And without Apple as the main client, Intel, in turn, had to bury the work on the modem chip.

Intel and Apple resumed cooperation on the expiration of the Apple deal with Qualcomm in 2016. That year, Apple introduced the iPhone 7. Some copies came with Qualcomm modems, while others used new modems from Intel.

Apple’s obligation to buy millions of wireless chips from Intel has allowed the latter to inject resources into their development. In a deal with Apple, Intel acquired VIA Telecom, one of the few companies that struggled to compete with Qualcomm in the CDMA chip market. Intel needed CDMA chips to make their wireless products competitive around the world, but the company could not develop them in the timeframe that Apple had appointed. The acquisition of VIA allowed Intel to speed up work on CDMA. However, Intel's estimates showed that the acquisition of VIA would have been financially disadvantageous without the procurement volumes that Apple had promised Intel.

Relationships with Apple helped Intel in another. Information that the next iPhone will use Intel's cellular chips has motivated cellular operators to help Intel test these chips in their networks. Intel also found that the status of chip supplier for Apple gave it greater weight in standards organizations.

Empire Strikes Back

Apple's deal with Intel presented a serious threat to Qualcomm's dominance in the cellular chip market. As soon as Intel developed the full range of cellular chips Apple needed to build the iPhone, Intel could, in turn, offer the same chips to other manufacturers of smartphones. This would strengthen the pressure lever of each manufacturer at the time of updating their licensing agreements with Qualcomm. Therefore, Qualcomm went to war against Apple and Intel.

Freed from the threat of Qualcomm with interrupted supplies, Apple launched an attack on high patent royalties requested by Qualcomm. Qualcomm responded by cutting Apple’s access to chips for new iPhone models, forcing Apple to rely solely on Intel for the release of 2018 models. Qualcomm sued Apple for violating patent law in courts around the world, and Apple forced the FTC to investigate Qualcomm's business practices.

This dispute has put Apple and Intel in a precarious position. Qualcomm tried to use its arsenal of patents to ban sales of iPhones in jurisdictions of different countries. If Qualcomm had won a victory in one of the major markets, this could force Apple to sit down at the negotiating table. Then, Qualcomm could force Apple to buy fewer chips from Intel, which would threaten the business of Intel's wireless chips — especially when other potential customers were reluctant to get in the way of Qualcomm's patent chainsaws.

At the same time, Apple relied on Intel to keep its phone at the forefront of wireless technology. Intel has successfully developed modem chips suitable for iPhone models 2017 and 2018, but in the next couple of years the wireless industry will be preparing for the transition to 5G technology. The iPhone is a premium product that needs to support the latest wireless standards. If Intel could not quickly develop chips for 5G, so that they could be used in the iPhone model of 2020, it would put Apple in an untenable position.

Apparently, it was the last option that was realized. Last year, Apple announced an agreement with Qualcomm on a wide range of issues, which requires Apple to pay a six-year license for Qualcomm patents. An hour later, Intel announced that it was ceasing to work on 5G generation chips.

Although all the details of what is happening are unknown to us, apparently, this year Apple began to doubt the ability of Intel to quickly develop 5G modem chips to meet all the needs of Apple. As a result, the opposition of Apple and Qualcomm was not viable, and Apple decided to close the deal, while it still has at least some trumps. Apple's decision to come to terms with Qualcomm immediately cracked up on the vine all attempts by Intel to create modem chips.

Qualcomm has long refused to sell patent licenses to competitors.

The story of Qualcomm's struggle with Apple and Intel illustrates how Qualcomm used its patent portfolio to support its chip monopoly.

Chip manufacturers typically obtain patents related to their chips, protecting their customers from patent issues. But Qualcomm refused to license its patents to competitors, which put them in a difficult position.

“Basically, the attitude of all customers with whom I spoke was such that before they consider buying 3G chipsets from MediaTek, we need to first enter into a license agreement with Qualcomm,” said Finbarr Moynihan, head of chip maker MediaTek .

If a chip maker requested a patent license from Qualcomm, Qualcomm promised not to sue that maker, but not its customers. Qualcomm also demanded that chip makers — that is, its direct competitors — sell these chips only to companies from Qualcomm’s list of “authorized buyers” already licensed by Qualcomm patents.

Needless to say, this put Qualcomm's competitors - as well as future competitors - at a disadvantage. The patent licensing scheme not only allowed Qualcomm, in fact, to levy sales tax on competitors, but also to choose customers for its competitors. Qualcomm insisted that other chip makers give it sales data for their chips, divided by their customers - sensitive commercial data that allowed Qualcomm to figure out what specific pressure to apply to prevent competitors from gaining strength.

The Qualcomm internal presentation, prepared a few days after the deal with MediaTek (on the slide labeled “MTK”), provides a ridiculously candid visualization of Qualcomm's competition with competitors:

- Make sure that MTK can cooperate with only clients with WCDMA SULA -> reduce the number of MTK clients on 3G to ~ 50

- Formulate and implement a GSM / GPRS strategy for destroying the profits of MTK with 2G -> Eliminate the revenues that MTK could invest in 3G

Here, “WCDMA SULA” refers to Qualcomm patent licenses. Qualcomm believed that by limiting MediaTek’s customer base to companies licensed by Qualcomm, it could guarantee that MediaTek would have no more than 50 customers for their future 3G chips. Meanwhile, Qualcomm sought to deprive MediaTek of funds to invest in chip development.

Several small chip makers, such as MediaTek and VIA, have agreed to unilateral deals with Qualcomm. More importantly, many larger companies were unable to enter the market, or were forced to withdraw from it, thanks to Qualcomm tactics.

Qualcomm refused to sell Intel patent licenses twice - in 2004 and 2009 - delaying access to the wireless modem market. A joint venture between Samsung and NTT DoCoMo for the production of chips called Project Dragonfly was refused by Qualcomm in 2011; as a result, Samsung produced some modem chips for itself, but did not offer others. Qualcomm refused LG a patent for a potential modem chip in 2015.

Qualcomm denied Texas Instruments and Broadcom patent licenses before they left the dial-up business in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

Honest, reasonable, without discrimination

When a group of standards develops another wireless standard, it compiles a list of patents necessary for its implementation - the most important patents for the standard. She then asks patent holders to give licenses to them under fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms (fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory - FRAND). Patent holders usually agree to this, since the inclusion of a patent in a standard increases its value.

However, Qualcomm did not keep its promises in the framework of FRAND. FRAND patents should be accessible to all who wish to obtain a license for them on equal terms - both customers and competitors. But Qualcomm refuses to license major patents to other manufacturers.

And when handset makers obtained such a license, Qualcomm usually combined them with its vast portfolio, which included other patents that did not fall under the FRAND terms, and in many cases did not apply to modem chips at all. As a result, phone manufacturers had to pay inflated prices for the most important patents from Qualcomm.

But no one had the opportunity to challenge the creative interpretation of the FRAND terms from Qualcomm. She did not sue other manufacturers directly, so they did not have an easy way to challenge the company's policy. Meanwhile, threats of interruptions in supply have kept clients from arguing with Qualcomm's licensing practitioners.

Judge Koch ruled that the inability of Qualcomm to follow the promises of FRAND is a violation of antitrust laws. Qualcomm had the obligation to grant patent licenses to anyone, she decided, and Qualcomm had an obligation to do it at reasonable rates — much lower than those that the company had appointed in recent years.

No more “no license - no chips”

Judge Lucy Koch

Judge Koch identified several changes needed to stop Qualcomm’s anti-competitive activities and restore competitive market balance.

The most important change is to disconnect Qualcomm's patent licensing and chip business. Koch ordered Qualcomm "not to make conditions for the supply of modem chips dependent on the status of patent licenses of the client." Qualcomm is obliged to renew all contracts for patent licenses, without threatening anyone with a refusal to supply modem chips.

Koch also ordered Qualcomm to license the most important patents to standards to other manufacturers within the framework of FRAND, preparing for arbitration of transactions, if necessary, in order to ensure an honest royalty. These licenses must be “exhaustive” - that is, Qualcomm is prohibited from litigating with the customers of manufacturers due to a violation of patent licenses by the manufacturer.

Thirdly, Koch forbids Qualcomm to enter into exclusive deals with customers. This means no more returns if the customer buys 85% or 100% of the chips from Qualcomm.

Patent expert Charles Duane believes that the decision of Koch "refers to the biggest problems that people faced in the framework of the behavior of Qualcomm."

Seriously, Samsung can benefit from this, one of the few large technology companies that have retained significant in-house production capabilities for modems. In recent years, Samsung has often released smartphones on its own Exynos chips in some markets, while selling Qualcomm chips on others - especially in the United States and China. The reasons for this strategy are unclear, but it is reasonable to assume that Samsung believes that in these countries it is in a more vulnerable position against Qualcomm's patent threats.

Now it will be easier for Samsung to use its own chips all over the world, simplifying the product design, which will give the company more scale savings for its own chips. As a result, Samsung may even begin to offer its chips to other manufacturers of smartphones - as she tried to do in 2011.

On the other hand, the Koch resolution may have appeared too late for Intel, which last month announced the completion of the development of its chips for 5G, and probably will not find the desire (and time) to restart the project.

However, Koch’s most important requirement will probably be seven years of tracking Qualcomm’s work by the courts and the FTC.

“I can imagine that next year, Qualcomm will find a new way to return to its old profit-making model,” Duan told us via email. Constant vigilance is required of the authorities to ensure Qualcomm’s submission to both the letter and the spirit of the Koch ordinance.

But first, it must be appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. In May, Qualcomm asked Koch to hold on to its decision until the appeals court expresses its opinion. Qualcomm customers and competitors will not be able to breathe freely until the appeal process ends.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/459612/

All Articles