One step closer to restoring the thymus

Monash Biomedicine Institute scientists have made progress in the rejuvenation of an aging immune system, identifying the factors responsible for reducing the thymus.

Thymus decreases with aging

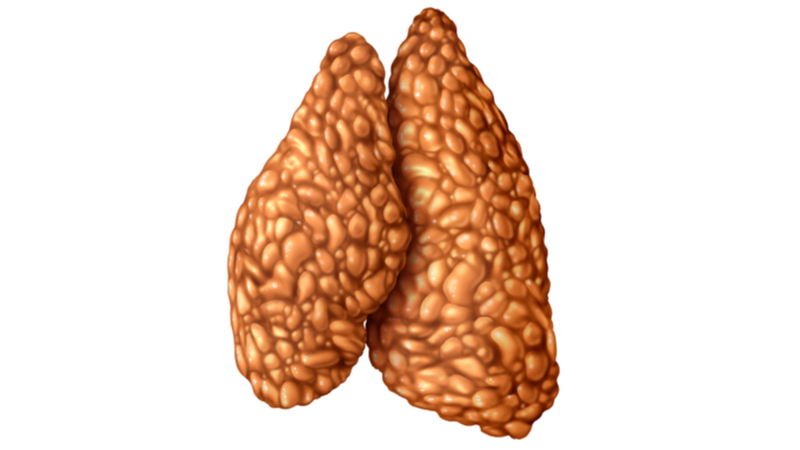

The thymus is one of the most important organs in the body, and it is there that thymocytes formed in the bone marrow become new T-cells before they mature in the lymph nodes to become the protectors of the adaptive immune system. However, as we get older, the thymus is increasingly replaced by fat and begins to decrease, and its ability to produce new T cells decreases sharply. This process is known as the involution of the thymus and actually begins shortly after puberty, so this is one of the aspects of aging that starts very early, although it takes many decades before its reduction causes serious problems.

Reducing the production of new T cells from the thymus leads to a decrease in the adaptive immune system and is part of the general aging of the immune system. The end result of the immunosensitivity process is that your body can no longer provide effective protection against disease, is improperly activated, leading to immune dysfunction and chronic inflammation .

Reduction of the thymus is associated with the risk of developing cancer, which increases dramatically with age, according to the concept of immunosensitive cancer. Immune aging also strongly correlates with multiple age-related pathologies, which is probably not surprising, given that the elderly immune system can no longer effectively and adequately respond to the invasion of pathogenic microorganisms.Although it has long been known that the thymus decreases with age, the exact mechanisms of this involution were not completely clear.

')

Downward spiral

New work has shed light on what leads to loss of function of the thymus in old age and, as a result, to disruption of the production of immune cells. New research published in the journal Cell has laid the foundation for the development of treatment methods that can help the thymus to restore its ability to produce T-cells and fight infections and diseases.

Researchers show that BMP4 and activin are growth and differentiation factors, which are key to self-renewal and differentiation of thymus epithelial stem cells, and that changes in their levels as a result of aging cause the loss of these epithelial cells. This loss results in a decrease in T-cell production in the thymus, which ultimately leaves us open to infections and diseases. This study is the first in the world, and identifies the main reason why we experience the loss of thymic epithelial stem cells, as well as the molecules and mechanisms that control this process.

The next step for scientists will be to find ways to reverse this decrease and re-enable the thymus to resume production of T-cells. Scientists believe that age-related changes in the thymus can be reversed, and now they are studying whether it is possible to design a therapy for the regeneration of thymic epithelial stem cells.

A key feature of immunological dysfunction with age is the progressive involution of the thymus tissue, which is responsible for the production of naive T cells. In this study, we described two main phases of thymic epithelial cell loss (TEC) during aging: blocking the differentiation of mature TEC from the pool of immature progenitors, occurring at the onset of puberty, followed by impaired bipotent differentiation of TEC precursors and depletion of Sca-1lo cTEC pools and mTEC specific precursors. We found that an increase in the production of follistatin contributes to their death. TEC loss is mainly due to the antagonism of the transmission of activin A signals, which, as we show, is necessary for TEC maturation and acts in dissonance with BMP4, which contributes to the preservation of TEC's predecessor pools. These results confirm that the imbalance of the signaling of activin A and BMP4 underlies the degeneration of the postnatal TEC pools during aging, and its circulation allows for a temporary increase in the pools of mature TECs.

Conclusion

Effective targeting of these pathways can lead to the restoration of not only the production of T-cells by the thymus, but also the diversity of T-cells. This can significantly improve the health of older people, who usually have poor or almost non-functional T-cell production as a result of thymus involution. If it is possible to develop a therapy that restores the thymus, restoring its functions to a more youthful level, it can improve the health of the elderly and reduce the risk of getting sick with many age-related pathologies and infectious diseases.

Some companies and research groups are currently engaged in thymus rejuvenation, and the available information, including animal experiments and preliminary human trials, allows us to believe that thymus regeneration is quite possible in the near future.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/459116/

All Articles