Professor who beat roulette

As a well-known explorer, he caught his luck, confounded casino owners around the world, and left the game with a fortune

On a warm May evening in 1969, a crowd of shocked players huddled around a worn-out roulette table in the Italian Riviera region. In the center stood a gangly 38-year-old professor of medicine in a crumpled suit. He just bet $ 100,000 ($ 715,000 on today's money) for one round of roulette. The croupier released a small white ball, and the room froze. Can't he get so lucky ... or maybe?

However, Dr. Richard Dzhareki did not surrender to the blind chance. He spent thousands of hours developing a brilliant winning method - and he will soon bring him a win equivalent to $ 8 million today.

From Nazi Germany to New Jersey

Richard Dzhareki was born in 1931 in the German city of Stettin in a Jewish family, and fell into a world of chaos. Germany was in the agony of the economic crisis, the support of the Nazi party of the Nazi Nazi Party with its anti-Semitic platform, which blamed the Jews for all the problems, was growing. Dzhareka's parents, a dermatologist and heiress of a large transport company, gradually lost everything they owned. Faced with the threat of internment and the early unleashing of World War II, they fled to America in search of a better life.

Hitler on German street in 1938, shortly after the flight of the Dzhareka family from the country

')

In New Jersey, young Dzhareki found an outlet in card games such as gin rummy, ramp, and bridge, and with pleasure “regularly won money” from friends. His gifted brain easily memorized numbers and statistics, and the young man went to study medicine - it was a noble deed approved by his father.

In the 1950s, Dzhareki gained a reputation as one of the largest medical researchers in the world. However, he had one secret: his real passion was hiding in the dark, musty corridors of the casino.

Strategy

Somewhere in 1960, the Jarekas caught fire with a passion for roulette, a game in which a small ball spins on a randomly numbered multicolored wheel, and the players make bets on where it lands. And although many thought that roulette was a game of chance, Dzhareki was convinced that it could be “defeated”.

He noted that at the end of each evening the casino changed cards and dice for new ones - however, expensive roulette wheels remained in place, and often served for decades until they were replaced with new ones.

Like other cars, these wheels wear out. Dzhareki began to suspect that minor defects - chips, dents, scratches, uneven surfaces - can lead to the fact that certain wheels can issue certain numbers more often than it happens in a truly random order.

Roulette, which Dzhareki played in the 60s

On weekends, the doctor traveled to and fro between two tables, operating and roulette, manually recording the results of thousands and thousands of roulette launches, and analyzing data for statistical anomalies.

“I conducted experiments until I worked out a draft of the system based on the previous winning numbers,” he told the Sydney Mornin Herald newspaper in 1969. “If in the previous rounds we won the numbers 1, 2 and 3, then I could determine which numbers were most likely to be winning in the next three rounds.”

Jackie’s approach was not new: Joseph Jagger , considered the pioneer of the so-called. “shifted wheel” strategies, won significant sums in the 1880s [ Apparently, this story was inspired by Jack London, writing the story “The Kid Dreams” / approx. trans. ]. In 1947, researchers Albert Gibbs and Roy Walford used this technology, bought a boat for the money and sailed into the Caribbean sunset. There was also Helmut Berlin , a turner, who in 1950 hired a team of buddies to monitor the work of roulettes, and won $ 420,000.

However, for Dzhareka it was not about the money. He wanted to bring the system to the ideal, repeat it and “win” the roulette. It was about winning the man at the car.

After several months of data collection, he took the saved $ 100 (set aside for a rainy day) and went to conquer the casino. Prior to that, he did not play gambling, and although he believed in his research, he knew that he was still opposed by the "element of chance."

In a few hours, he turned $ 100 into $ 5000 ($ 41,000 in today's money). Confirming the performance of the system, he switched to more serious rates.

In the mid-60s, Dzhareki moved to Germany and got a job at the University of Heidelberg to study electrophoresis and criminal medicine.

He recently received a very prestigious award (one of only 12 handed around the world) for his work on international cooperation in the field of medicine, and entered the elite group of doctors and scientists. However, Dzhareki was eager for another prize: he looked towards the nearby casinos.

Dzhareki (center) gathers a crowd in a European casino

On European roulettes, the odds were higher than in America: they had 37 cells with numbers, not 38, which reduced the casino's advantage over the player from 5.26% to 2.7%. And, as Dzhareki later discovered, they were just right for him: old, broken-down, full of physical defects.

He and his wife walked dozens of roulettes at casinos across Europe, from Monte Carlo (Monaco) to Divonne-les-Bains (France) and Baden-Baden (Germany). The couple scored a team of 8 assistants, who settled in the casino, and recorded the results of the roulette work - sometimes 20,000 starts per month. Then, in 1964, he struck the first blow.

Having identified the defective wheels, he borrowed £ 25,000 from the Swedish financier and spent 6 months to implement his strategy without hiding. By the end of the period, he earned £ 625,000 (approximately $ 6,700,000 today).

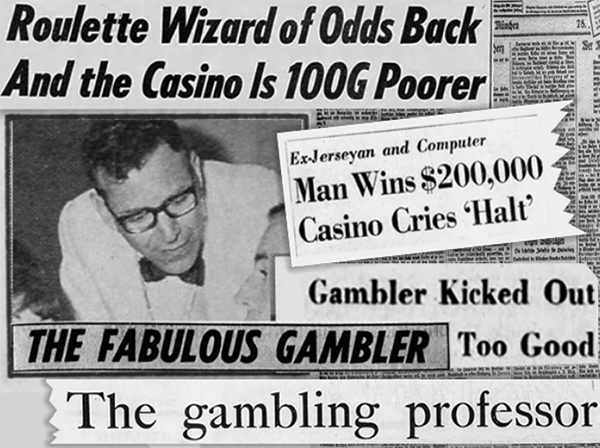

Victories Dzhareki hit the headlines around the world, from Kansas to Australia. Everyone wanted to know his “secret” - but he knew that in order to continue to win, he needed to hide the true methodology.

Therefore, he invented a fashionable press tale: he allegedly daily counted the results of the roulette, and then fed the results to the Atlas supercomputer, which prompted him to the winning numbers.

In those days, as the gambling historian Russell Barnhart wrote in the book “Beating the Wheel”, “Computers were considered creatures from space. Few people, even among casino managers, knew them well enough to distinguish myths from reality. ”

Hiding behind this technological ploy, Dzhareki continued to monitor defective tables - and prepared for the next major step.

Casino owner's worst nightmare

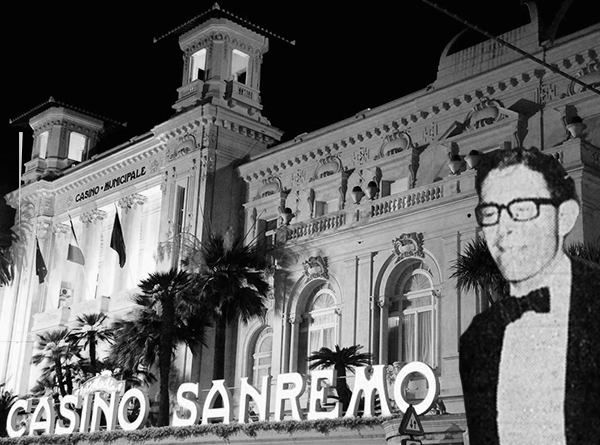

Charged with cash, Dzhareki acquired luxury apartments near San Remo, a luxurious Italian casino on the shores of the Mediterranean. Diligent observations helped him to determine the table on which the number 33 fell out much more than usual - as a result of "constant friction of the ball on the wheel." In the spring evening of 1968, he arrived at his white Rolls Royce on this gambling sin and won about $ 48,000 (today’s $ 360,000) for three days.

Eight months later, he returned after winning $ 192,000 ($ 1,400,000) for one weekend at two different roulettes twice in one night, which emptied the money in the casino. The casino owner, who was on the verge of ruin, had no choice but to prohibit Jareka from visiting his establishment for 15 days "for playing too good."

Casino "San Remo", where Dzhareki won a large sum

In the evening at the end of the ban, Dzhareki returned and won another $ 100,000 ($ 717,000) - the casino even had to write out a promissory note.

When visiting a casino around Dzhareki, large crowds gathered to observe the master's work. Many tried to repeat the rates behind him, placing small bets on the same numbers.

Trying to outwit the Dzhareks, the casino owners changed his favorite roulettes of places every evening. However, the professor remembered every vein in the tree, every chip, scratch and color defect - and always found the right ones.

“It has become a threat to all European casinos,” said the Sydney Mordern Herald, the Lairder. “I don’t know how he does it, but I would have been happy if he had never returned to my casino.”

“If the casino managers don't like losing,” Jareki retorted, “let them sell vegetables.”

As a result, San Remo surrendered and replaced all 24 roulettes, spending a significant amount. The management decided that it was the only way to stop the best player from all that they had seen.

In the following decades, casinos began to actively invest in roulette tracking systems, tracking defects and creating wheels that are less susceptible to distortion. Today, most of the wheels are digital, and work on algorithms that guarantee casino winnings.

With a tape measure in the grave

In general, Dzhareki won about $ 1,250,000 (today's $ 8,000,000) at the casino, making major bets on defective roulettes from 1964 to 1969.

The Italian newspaper Il Giorno called him "the most successful roulette player" - a skinny academic who did not look like a "gambler." Once at the university, he was considered a “nerd,” and now he has become “the hero of all university students.”

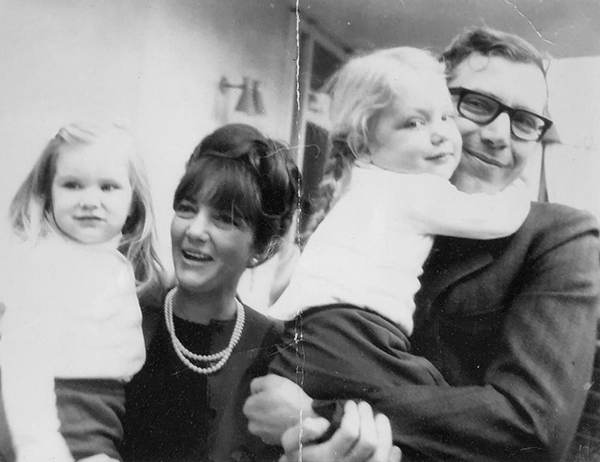

Richard Dzhareki with family

In 1973, Dzhareki moved back to New Jersey, starting a new career as a commodity broker. With the help of his brother, the billionaire, he increased his fortune 10 times. He also passed on his passion for games to his son, who at the age of 9 became the youngest chess champion in history.

The casino owners periodically harassed him with offers of partnership, but he never agreed: “He liked to take money from the casino,” his wife, Carol, told the New York Times, “not to give them away.”

In the early 90s, Jareki was tired of Atlantic City and moved to Manila, where gambling flourished and was poorly regulated. He lived there until his death in 2018, at the age of 87.

Having settled in the corner of a noisy gaming room, surrounded by neon lights and playing machines, he made his last bet. The wheel spun and spun. And, like many times before, the little white ball hit the number he chose.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/457892/

All Articles