Security Week 26: Google Spam

Most often in our weekly digests we discuss some new facts or events related to information security. In some cases, such discoveries are of purely theoretical interest: for example, Specter- type vulnerabilities in modern processors are unlikely to be exploited en masse in the near future. But freshly discovered critical vulnerabilities in common programs usually require immediate action if these programs are used in your work or personal infrastructure. From recent events, zero-day in Windows , a vulnerability in the Exim mail server, or even a very fresh hole in the VLC player belong to such.

But there are security issues that have been around for a long time, evolve slowly and are being exploited en masse. In the information space, they receive less attention: well, it is clear that there is spam and the associated large-scale fraud, and now what? Let's take a look at this boring topic for a change, especially since there is a reason. Recently, a detailed review of spamming techniques through numerous Google services was published on the Kaspersky Lab blog. If you are unlucky, you are faced with such annoying attacks yourself. It happened with one of the authors of this digest. In this post, we will add recommendations to the review of methods and, using spam as an example, we will talk about privacy issues. More specifically, how access to your services is essentially limited to two sequences of letters and numbers that everyone knows.

Let's start with the “captain” application: access to any service in your Google account is possible at your email address. As a user, this is convenient for you: register your mail and immediately receive an instant messenger, a place to store photos and other files, a calendar and a contact manager, and much more. Such a construction is doubly convenient for spammers, and for some time spam began to take on new forms. It is now not only sending unsolicited messages to your inbox. Having access to the metadata of millions of accounts, Google is struggling with traditional spam quite well, and in the middle of the two thousandth it was a serious advantage at the time of the new mail service GMail.

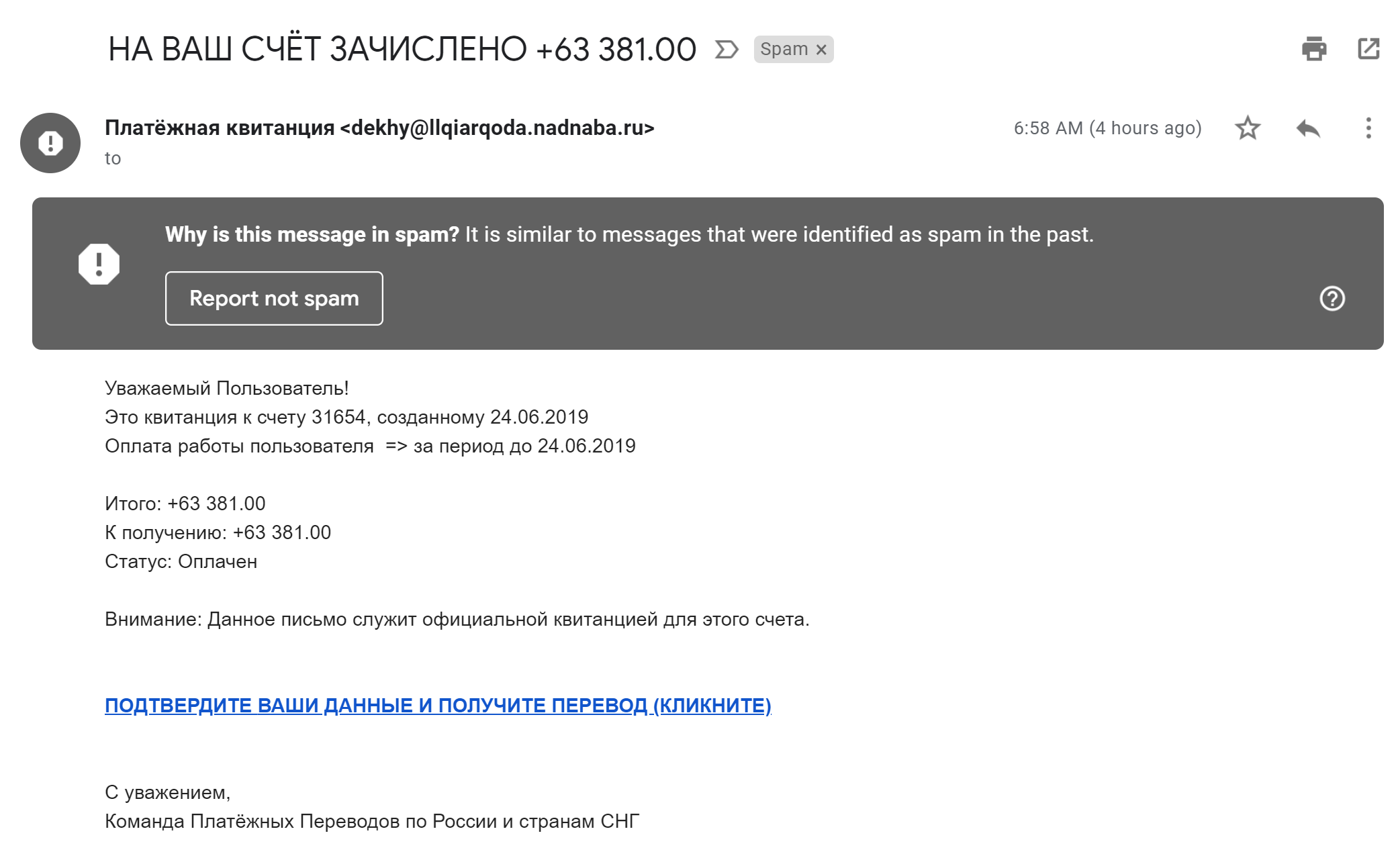

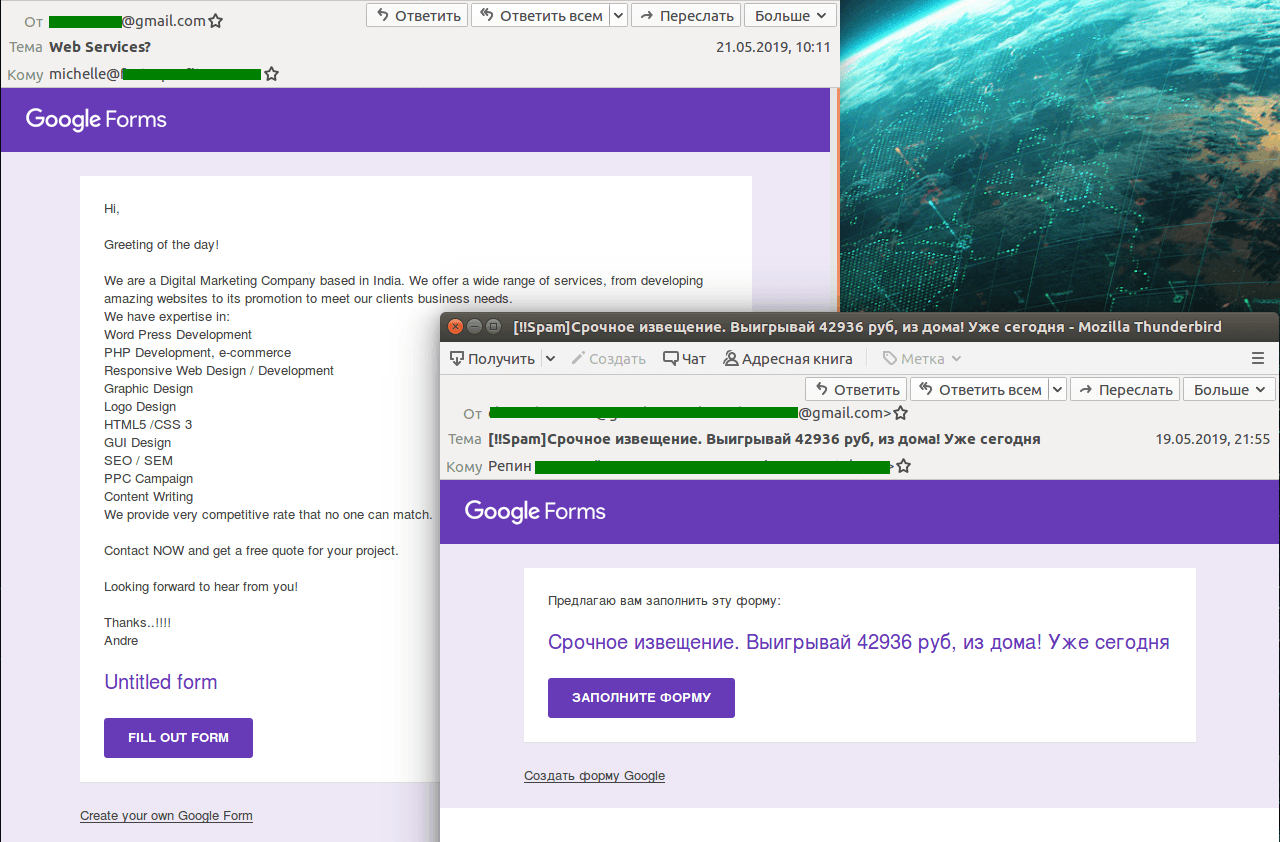

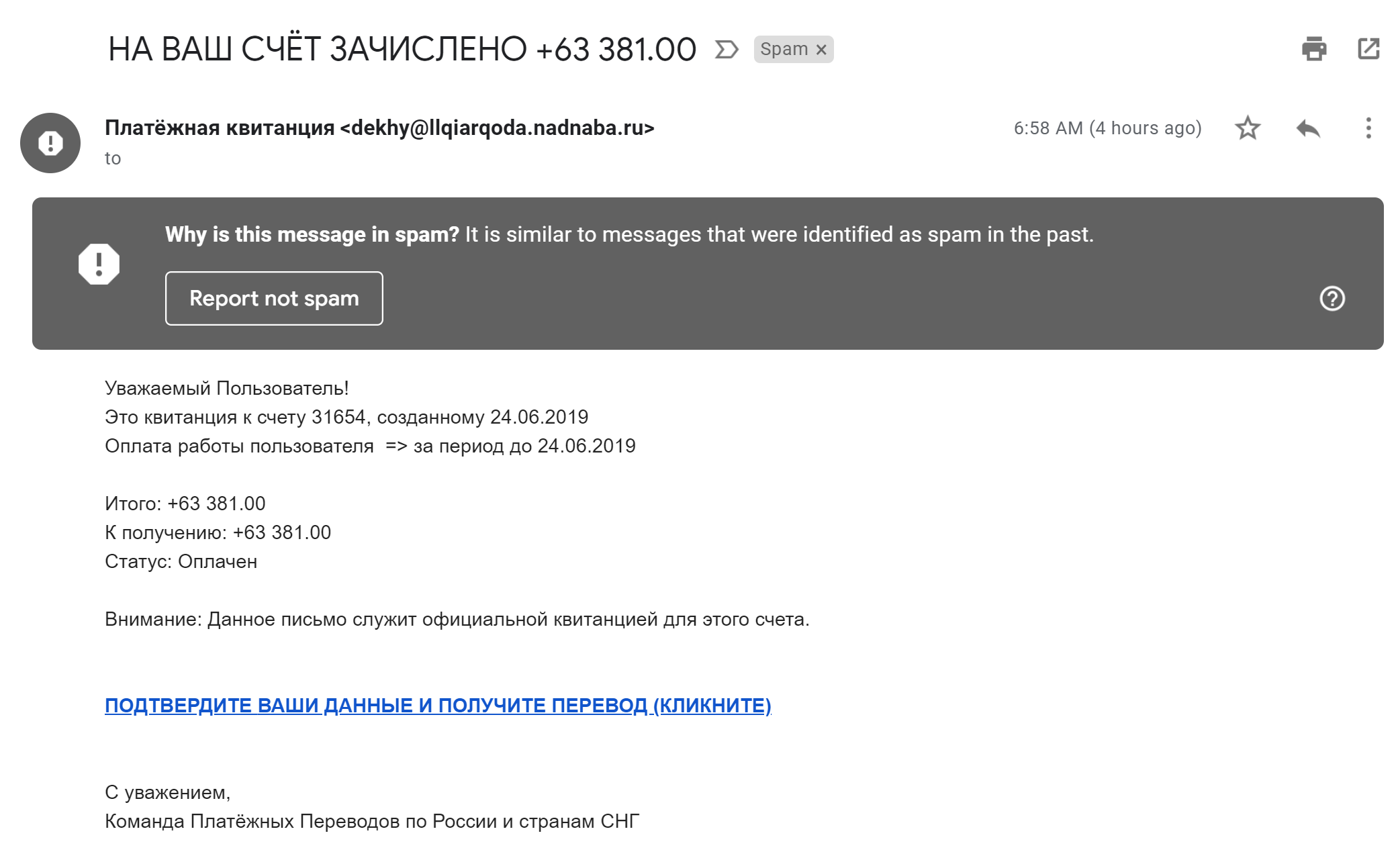

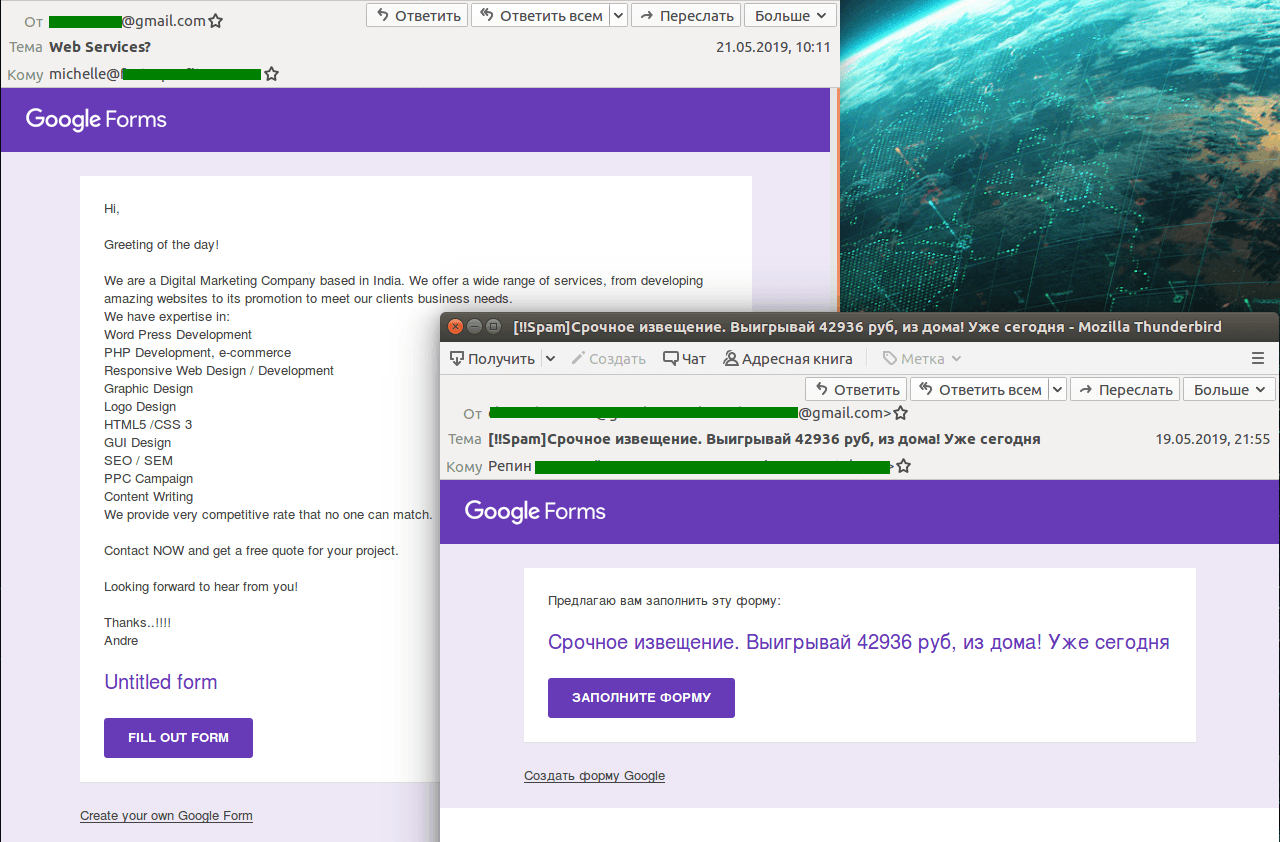

Such messages will be in the Spam folder with a probability close to 100%. Therefore, spammers have begun to exploit other Google services: by performing an action in this service, you can trigger a message to the victim using your own company servers. This is how spam appeared through Google forms.

')

That is: a form is created, it is filled in, your address is indicated, a notification comes to you (thanks for filling out the form “You received a lot of money, you will receive it sooner”). By manipulating the names of the form and individual fields, you can create a message that pleases the offender - with reference to fraud with questionnaires, with some kind of non-working financial schemes, with inflated cryptobirds. Today we will not explore what exactly spammers are trying to get from you, it does not matter in the context of this story. Such spam can be both massive and targeted.

It should be noted that, according to the subjective impressions of the author of these lines, the peak of spam through Google-form was a year or two ago, now there are almost no such messages. But any third-party services are being exploited, in the logic of which there is an e-mail sending to the user. As a result, accounts are registered in online stores to your email, trying to insert a spam link in the “username” field, attack web forms with the “fill in and get the message” mechanics, use technical support systems. Suffers from this, including the business, as a rule, small, having only the basic tools of working with users on the site. But back to Google. Spam through the Forms, apparently, was able to be limited or eradicated, but right now another hole in the logic is actively being exploited: spam through the Calendar.

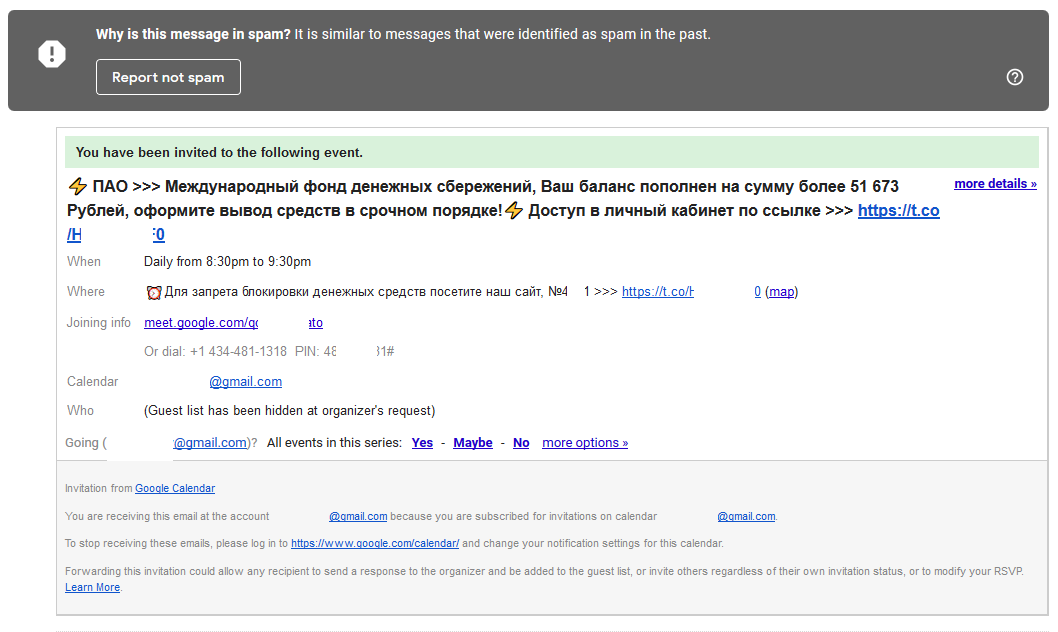

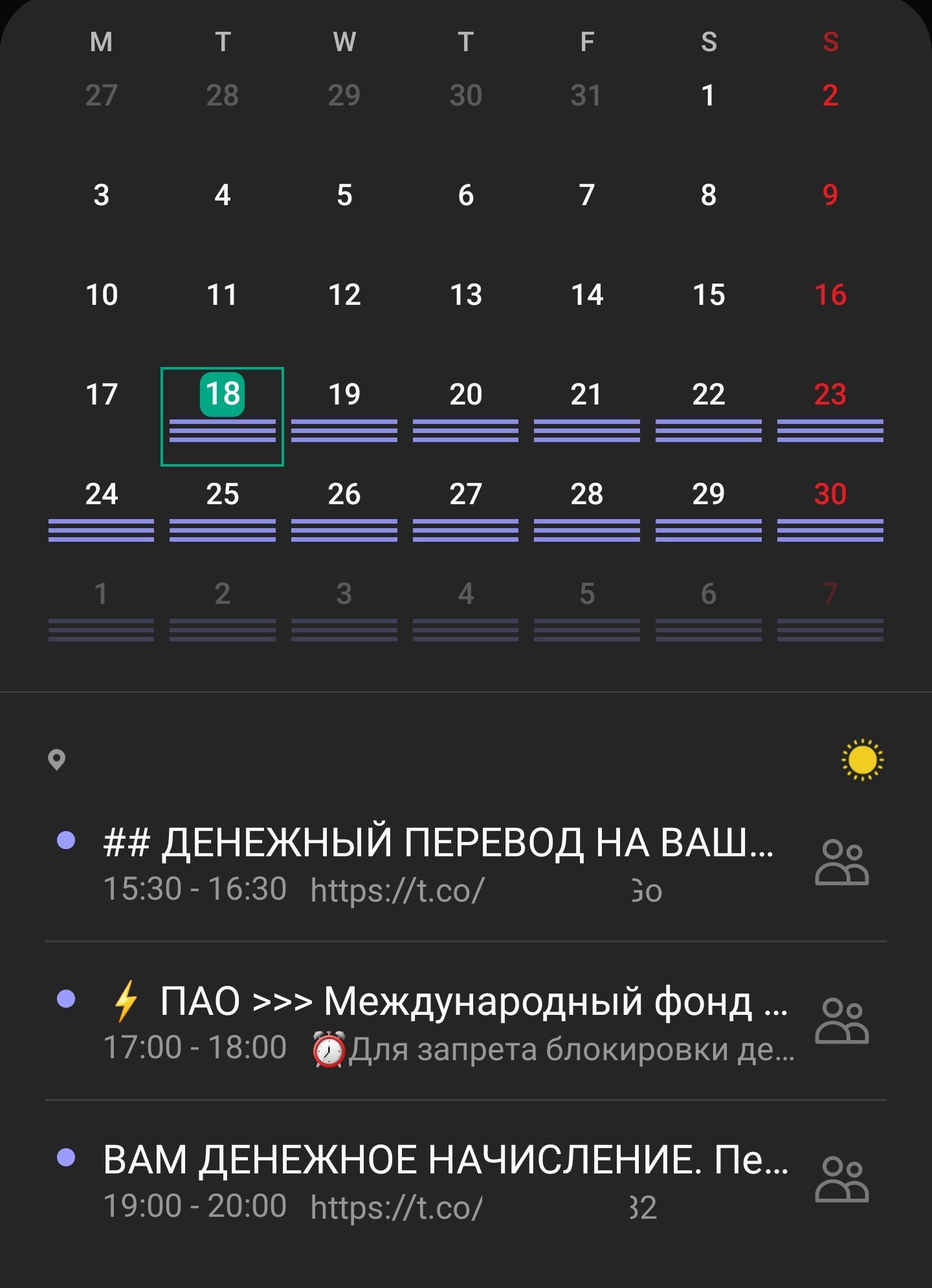

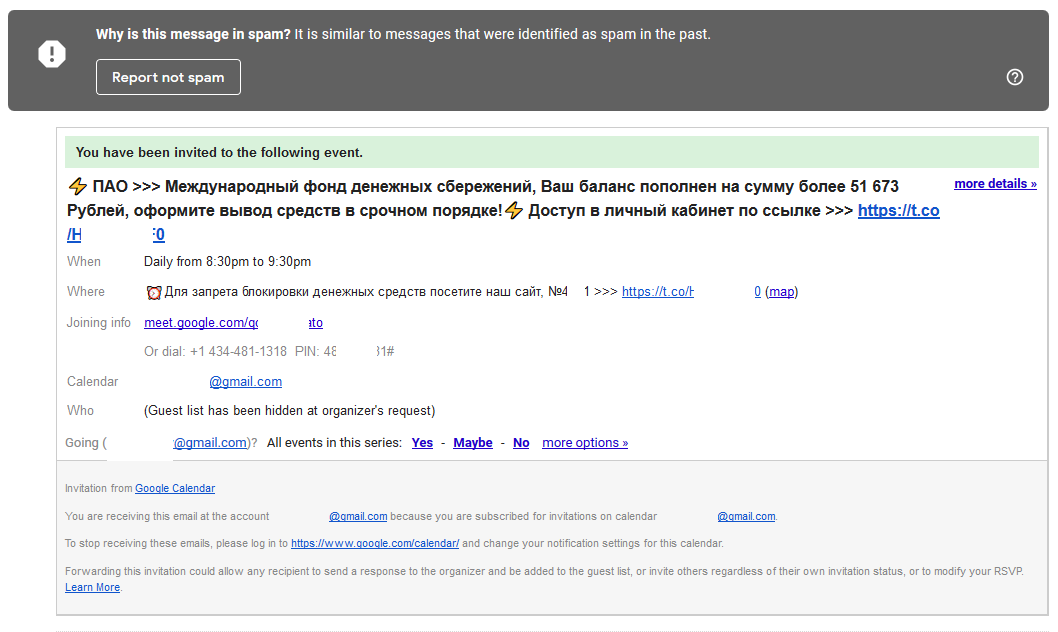

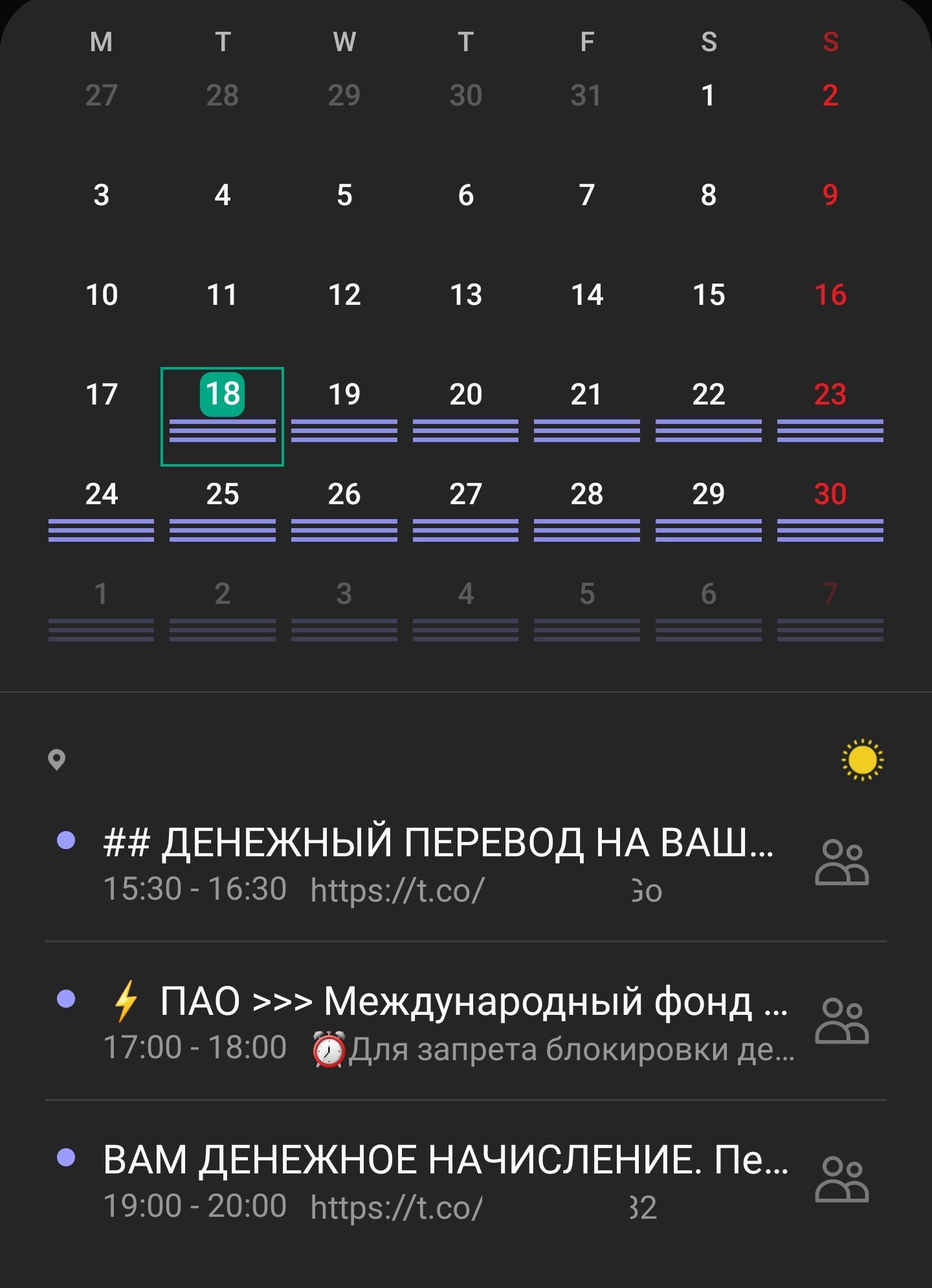

What do we see here? Someone creates an event and sends an invitation to random users on the network, including you. Actually “spam content” is the name of the event, but here it is interesting that the event is not a one-time event, but a daily one. Wait, but GMail has correctly identified this message as spam - so everything is in order? But no: with the default calendar settings, all invitations are automatically added to your schedule, regardless of the status in the mail.

And now this is a real pain, to which both the actions of spammers and the approach of Google, which, of course, wants to simplify the use of their services as much as possible. If spam through the Forms is a bit annoying because it periodically punched Google filters (which usually does not happen in other cases), here you get a notification on the phone, with sound, and it is possible that at night.

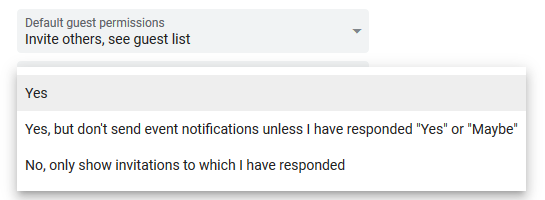

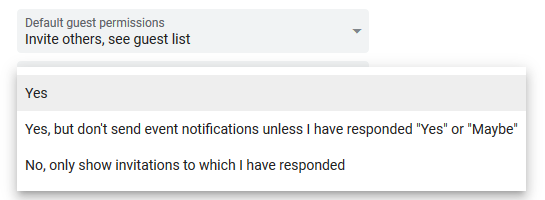

This setting solves the problem once and for all. If you select the third option “show only invitations to which there was an answer”, then spam in the calendar and in the phone disappears (not counting those “events” that have already managed to get there - they must be removed from the calendar manually). Interestingly, this setting is not available from a mobile phone and is only present in the desktop version. All for your convenience!

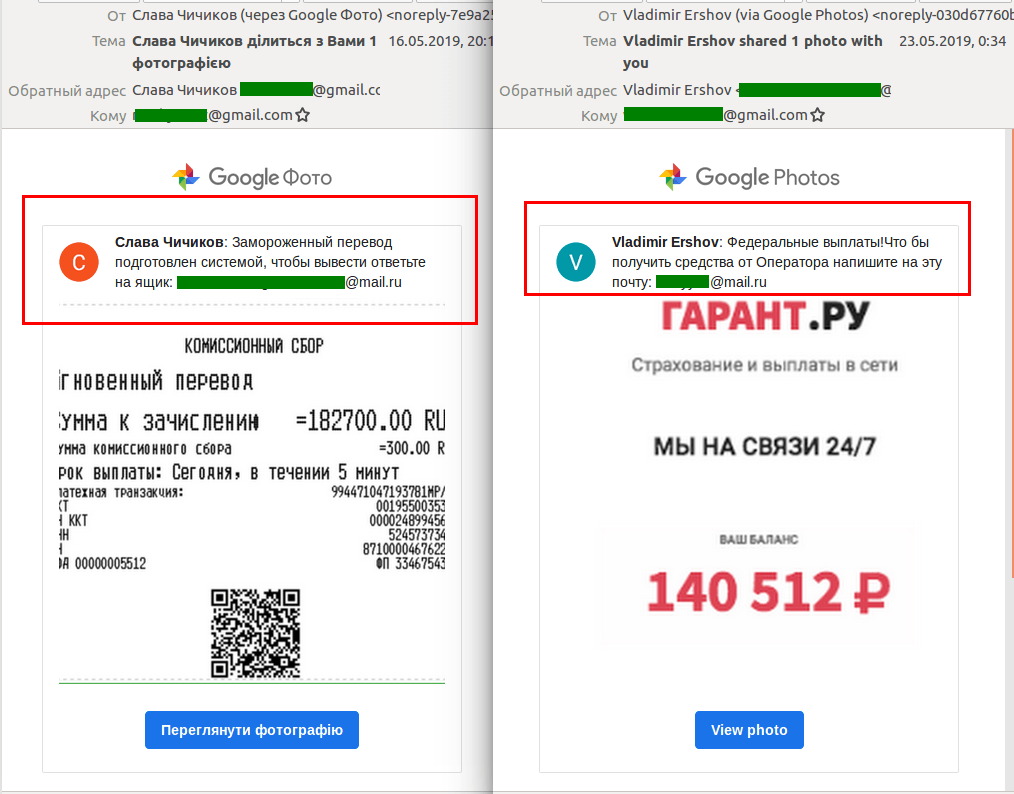

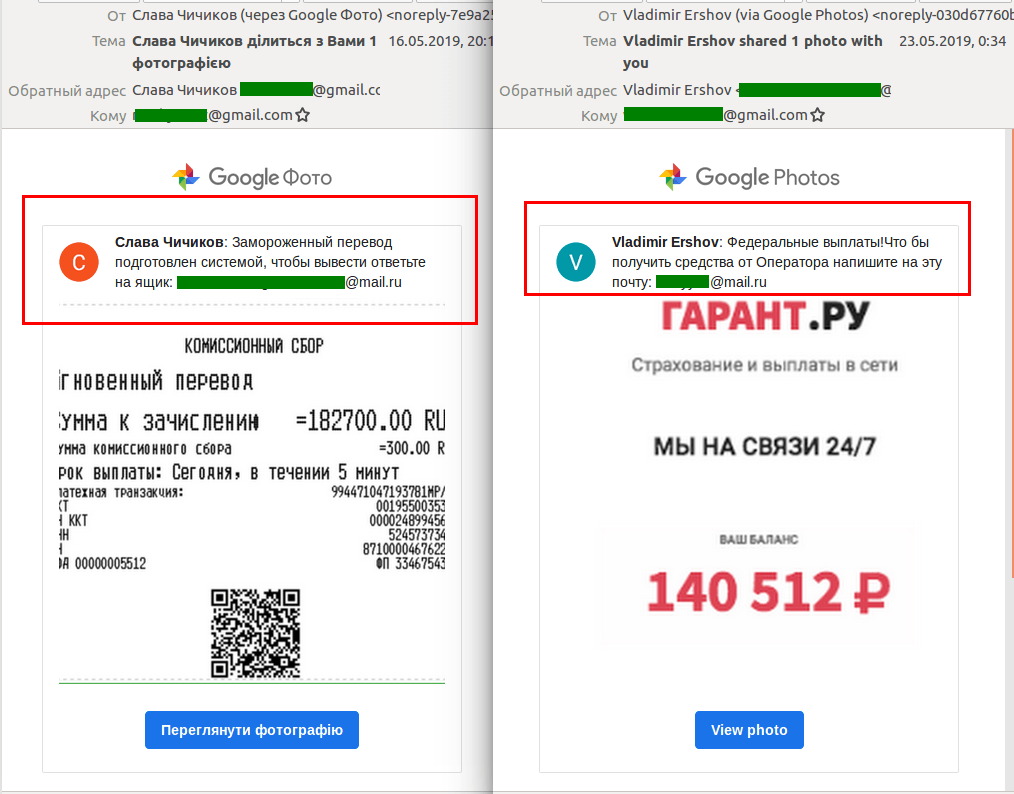

The article gives two more examples of unconventional spam through Google services: notifications from Google Photos and spam through documents on Google Drive. You can also add spam through the Google messenger, which changed a dozen names in its history. After analyzing all these examples, we can confine ourselves to the recommendation “do not click on suspicious links and do not open suspicious files”. And this is really the first thing to keep in mind when receiving spam by any means. But it's not only that.

Last week, the publication ZDNet published another story of the victim of a SIM-card substitution. The attacker got access to the phone of the author of the article: he called the cellular operator, informed the personal data of the owner and requested a re-release of the sim card. After that, he entered the Google account, intercepted access to Twitter and disconnected the owner of the Internet (also provided by Google). Thus, he made it as difficult as possible to restore access to accounts, and even tried (fortunately, unsuccessfully) to buy Bitcoins from a victim’s bank account for $ 25,000. Two interesting points in this article: the replacement of a SIM card by an outsider occurred twice (!), And attempts to contact Google support were successful, but not immediately.

It seems to be not directly related to spam, but in fact it is possible to identify a common problem: in a typical scenario, access to the most important digital assets is tied to your phone number and email address. That is, the fact that it is known to many people and in most cases is easily detected by intruders. In the worst case, this leads to a loss of time, money and reputation, as described in the article ZDNet and in many other examples. In the "best" this leads to loss of time, phone calls in the middle of the night and mess in the mailbox. But wait, there's nothing good about that either!

If your mailbox is used to communicate with a large number of people, especially for business, you are unlikely to change it due to spam attacks. It can be considered an inevitable evil. Service providers (this concerns not only Google) should definitely improve the user's protection against the exploitation of these same services by attackers. Users can be advised not to put all the eggs in one basket: to access the most important digital resources (for someone it could be a bank account, for someone - a Twitter account) to get a separate postal address and even a phone number that does not know no one. Yes, it is inconvenient! In 2004, when GMail postal service appeared, Google gained a competitive advantage by making mail convenient (making it easy to search before). The next leader in the digital services market can become one if it resolves the network inconvenience, and simply the threats of today.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend to treat any opinions with healthy skepticism.

But there are security issues that have been around for a long time, evolve slowly and are being exploited en masse. In the information space, they receive less attention: well, it is clear that there is spam and the associated large-scale fraud, and now what? Let's take a look at this boring topic for a change, especially since there is a reason. Recently, a detailed review of spamming techniques through numerous Google services was published on the Kaspersky Lab blog. If you are unlucky, you are faced with such annoying attacks yourself. It happened with one of the authors of this digest. In this post, we will add recommendations to the review of methods and, using spam as an example, we will talk about privacy issues. More specifically, how access to your services is essentially limited to two sequences of letters and numbers that everyone knows.

Let's start with the “captain” application: access to any service in your Google account is possible at your email address. As a user, this is convenient for you: register your mail and immediately receive an instant messenger, a place to store photos and other files, a calendar and a contact manager, and much more. Such a construction is doubly convenient for spammers, and for some time spam began to take on new forms. It is now not only sending unsolicited messages to your inbox. Having access to the metadata of millions of accounts, Google is struggling with traditional spam quite well, and in the middle of the two thousandth it was a serious advantage at the time of the new mail service GMail.

Such messages will be in the Spam folder with a probability close to 100%. Therefore, spammers have begun to exploit other Google services: by performing an action in this service, you can trigger a message to the victim using your own company servers. This is how spam appeared through Google forms.

')

That is: a form is created, it is filled in, your address is indicated, a notification comes to you (thanks for filling out the form “You received a lot of money, you will receive it sooner”). By manipulating the names of the form and individual fields, you can create a message that pleases the offender - with reference to fraud with questionnaires, with some kind of non-working financial schemes, with inflated cryptobirds. Today we will not explore what exactly spammers are trying to get from you, it does not matter in the context of this story. Such spam can be both massive and targeted.

It should be noted that, according to the subjective impressions of the author of these lines, the peak of spam through Google-form was a year or two ago, now there are almost no such messages. But any third-party services are being exploited, in the logic of which there is an e-mail sending to the user. As a result, accounts are registered in online stores to your email, trying to insert a spam link in the “username” field, attack web forms with the “fill in and get the message” mechanics, use technical support systems. Suffers from this, including the business, as a rule, small, having only the basic tools of working with users on the site. But back to Google. Spam through the Forms, apparently, was able to be limited or eradicated, but right now another hole in the logic is actively being exploited: spam through the Calendar.

What do we see here? Someone creates an event and sends an invitation to random users on the network, including you. Actually “spam content” is the name of the event, but here it is interesting that the event is not a one-time event, but a daily one. Wait, but GMail has correctly identified this message as spam - so everything is in order? But no: with the default calendar settings, all invitations are automatically added to your schedule, regardless of the status in the mail.

And now this is a real pain, to which both the actions of spammers and the approach of Google, which, of course, wants to simplify the use of their services as much as possible. If spam through the Forms is a bit annoying because it periodically punched Google filters (which usually does not happen in other cases), here you get a notification on the phone, with sound, and it is possible that at night.

This setting solves the problem once and for all. If you select the third option “show only invitations to which there was an answer”, then spam in the calendar and in the phone disappears (not counting those “events” that have already managed to get there - they must be removed from the calendar manually). Interestingly, this setting is not available from a mobile phone and is only present in the desktop version. All for your convenience!

The article gives two more examples of unconventional spam through Google services: notifications from Google Photos and spam through documents on Google Drive. You can also add spam through the Google messenger, which changed a dozen names in its history. After analyzing all these examples, we can confine ourselves to the recommendation “do not click on suspicious links and do not open suspicious files”. And this is really the first thing to keep in mind when receiving spam by any means. But it's not only that.

Last week, the publication ZDNet published another story of the victim of a SIM-card substitution. The attacker got access to the phone of the author of the article: he called the cellular operator, informed the personal data of the owner and requested a re-release of the sim card. After that, he entered the Google account, intercepted access to Twitter and disconnected the owner of the Internet (also provided by Google). Thus, he made it as difficult as possible to restore access to accounts, and even tried (fortunately, unsuccessfully) to buy Bitcoins from a victim’s bank account for $ 25,000. Two interesting points in this article: the replacement of a SIM card by an outsider occurred twice (!), And attempts to contact Google support were successful, but not immediately.

It seems to be not directly related to spam, but in fact it is possible to identify a common problem: in a typical scenario, access to the most important digital assets is tied to your phone number and email address. That is, the fact that it is known to many people and in most cases is easily detected by intruders. In the worst case, this leads to a loss of time, money and reputation, as described in the article ZDNet and in many other examples. In the "best" this leads to loss of time, phone calls in the middle of the night and mess in the mailbox. But wait, there's nothing good about that either!

If your mailbox is used to communicate with a large number of people, especially for business, you are unlikely to change it due to spam attacks. It can be considered an inevitable evil. Service providers (this concerns not only Google) should definitely improve the user's protection against the exploitation of these same services by attackers. Users can be advised not to put all the eggs in one basket: to access the most important digital resources (for someone it could be a bank account, for someone - a Twitter account) to get a separate postal address and even a phone number that does not know no one. Yes, it is inconvenient! In 2004, when GMail postal service appeared, Google gained a competitive advantage by making mail convenient (making it easy to search before). The next leader in the digital services market can become one if it resolves the network inconvenience, and simply the threats of today.

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this digest may not coincide with the official position of Kaspersky Lab. Dear editors generally recommend to treat any opinions with healthy skepticism.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/457434/

All Articles