Do I need a pillow astronauts?

By all accounts, good sleep in space is quite normal. After conducting scientific experiments and rigorous physical exercise, astronauts and astronauts on the International Space Station float to their soft sleeping boxes, in which there is enough space to accommodate them, as well as a few personal belongings, including a laptop attached on the wall, which brightens their personal area. In order not to cruise around the station in zero gravity while sleeping, the astronauts climb into a sleeping bag, tightly tied to the wall. But as it turned out, in the bedrooms of astronauts there are no pillows. Scientists motivate this by the fact that in microgravity it is not needed, because head during sleep naturally leans forward.

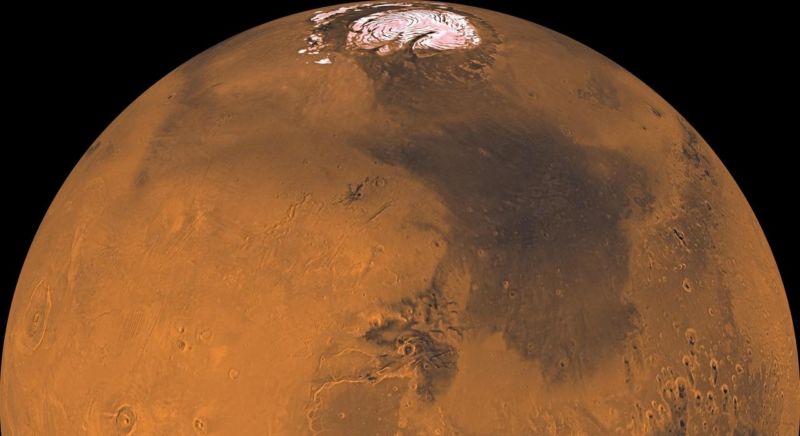

But just the fact that pillows are not needed in space does not mean that astronauts should not have them. The pillow is the main attribute of comfort, rest and finding peace. After all, people bring their own pillows to the wards of hospitals for a more comfortable pastime. So why not use it in space? Future astronauts who are preparing to make long flights to Mars, according to NASA estimates, will be in flight for at least 1000 days . They may very much want a pillow to feel the comfort and more often to remember their home on Earth.

These are the considerations adhered by Tibor Balint, chief designer of the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Balint spends his time looking for ways to incorporate the principles of art and design into human space endeavors. Now that mankind is on the threshold of a manned flight to Mars, Balint believes that the architects of the mission should begin to meet the higher psychological needs of astronauts.

')

As described in detail in an article recently published in Acta Astronautica, Balint and his colleague Chan Hee Lee, an associate professor at the Royal College of Art, seek to create objects that will provide comfort, reduce stress, and improve the individual characteristics of astronauts in the many years mission to the red planet. The authors' tandem eventually settled on the pillow as an ideal subject. Astronauts may not physically need a pillow for sleeping in space, but Baliant believes that the process of creating the head restraint itself will allow them to think that space travelers need it in addition to the basics of life support.

In the entire history of space exploration, astronauts have always been in visual contact with the Earth and on direct telecommunications with the MCC. Whether on the ISS or on the surface of the moon, they could maintain constant radio communication, see their home planet.

For astronauts who have completed the first mission to Mars, the situation will be noticeably different. The radio will go with a delay of 20 minutes both on reception and on the transfer of messages. When astronauts look in the windows of their interplanetary spacecraft, they will see not the sunrise over the blue planet, but the blackness of deep space. They will have a lot of downtime on the way, and time can deal a psychological blow to unprepared astronauts.

“In a sense, you will be in soloing for three years,” says Balint. “That's why we need to start exploring the needs of a higher level, because without them, people will go crazy.”

"Product, Resilience and Delight"

According to psychologist Abraham Maslow, as soon as the basic needs of a person — food, housing, security — are met, a person becomes motivated to meet the needs of a higher level, namely friendship, intimacy and creative abilities. Meeting these higher needs, according to Maslow’s theory, is the key to psychological well-being.

Maslow was not the first to try to understand basic needs. More than 2,000 years ago, the chief Roman architect, Vitruvius, applied this type of thinking to architecture, calling it “goods, resilience and delight” three essential qualities for human habitation. In the first 50 years of the cosmic era, the first two qualities prevailed. What was missing, according to Balint, is Vitruvian delight.

This is where the space pillow appears. To overcome isolation and monotony, astronauts will need various stimulating ways to interact with the environment. As Balint and Lee quickly discovered, the possibilities of “human interaction with the material” in the pillow design are enormous. They can focus on physiological considerations and arrange the pillow as a neck brace. Or they could satisfy the astronauts, filling the pillow with a relaxing scent. Perhaps they could install sensors and speakers in the pillow, which would determine when the astronaut fell asleep and play relaxing music. Alternatively, they could make the pillow interactive.

Balint and Lee developed a set of space pillows, each of which was designed to meet some or all of the higher-level needs that they identified for astronauts. These designs included full-face hoods with color-changing visors, headphones, and neck support; inflatable pillow "Space Angel", worn as a halo, which produces relaxing aromas; and a semi-rigid helmet that can be physically attached to the wall of an astronaut's bedroom. Ultimately, Balint and Lee decided that the pillowcases seemed rather uncomfortable and could raise safety concerns from NASA.

"Seamless"

The pillow design chosen by them is very similar to a regular pillow. In a model published in their newspaper, a shallow foam padding is attached to the wall of the astronaut's bedroom. Although Balint recognized the similarity of this project with what already exists on the ISS, he stressed the “seamless” connection of the pillow to other objects in the astronaut's premises. These can include aromatic devices, loudspeakers, or relaxing lighting displays that can be connected to the pillow using small sensors. Instead of integrating the speakers and displays into the pillow itself, this object is rather a “disconnected space pillow” integrated with a network of external objects. The sensors in the pillow can detect when, say, an astronaut fell asleep, and the light in the sleep unit faded out.

At the moment, the pillow of Balint and Lee remains purely conceptual. Balint says that the discussion of the texture, color or softness of the pillow is secondary. An important feature of the space pillow is that it can serve as an anchor for discussions about the psychological well-being of astronauts. As the design of the space habitat is gaining momentum, Balint hopes that his space pillow will remind engineers that artists and designers should also be involved in the conversation.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/454708/

All Articles