Technical details of recent Firefox extensions crash

About the author. Eric Reskorla - Technical Director, Firefox Mozilla Group

Recently, an incident occurred in Firefox, when most add-ons (extensions, add-ons) stopped working. This is due to an error on our part: we did not notice that one of the certificates, which is used to sign additions, has expired, which led to the disconnection of the vast majority of them. Now that we have fixed the problem, and most of the additions have been repaired, I would like to tell you in detail what happened, why, and how we fixed everything.

Although many use Firefox out of the box, the browser also supports a powerful extension mechanism. They add third-party features to Firefox that extend the features we offer by default. Currently, there are more than 15,000 Firefox add-ons: from ad blocking to managing hundreds of tabs .

Firefox requires that all installed add-ons are digitally signed . This requirement is intended to protect users from malicious extensions, requiring a minimum standard of verification by Mozilla staff. Before we introduced this requirement in 2015, we had serious problems with malicious extensions.

')

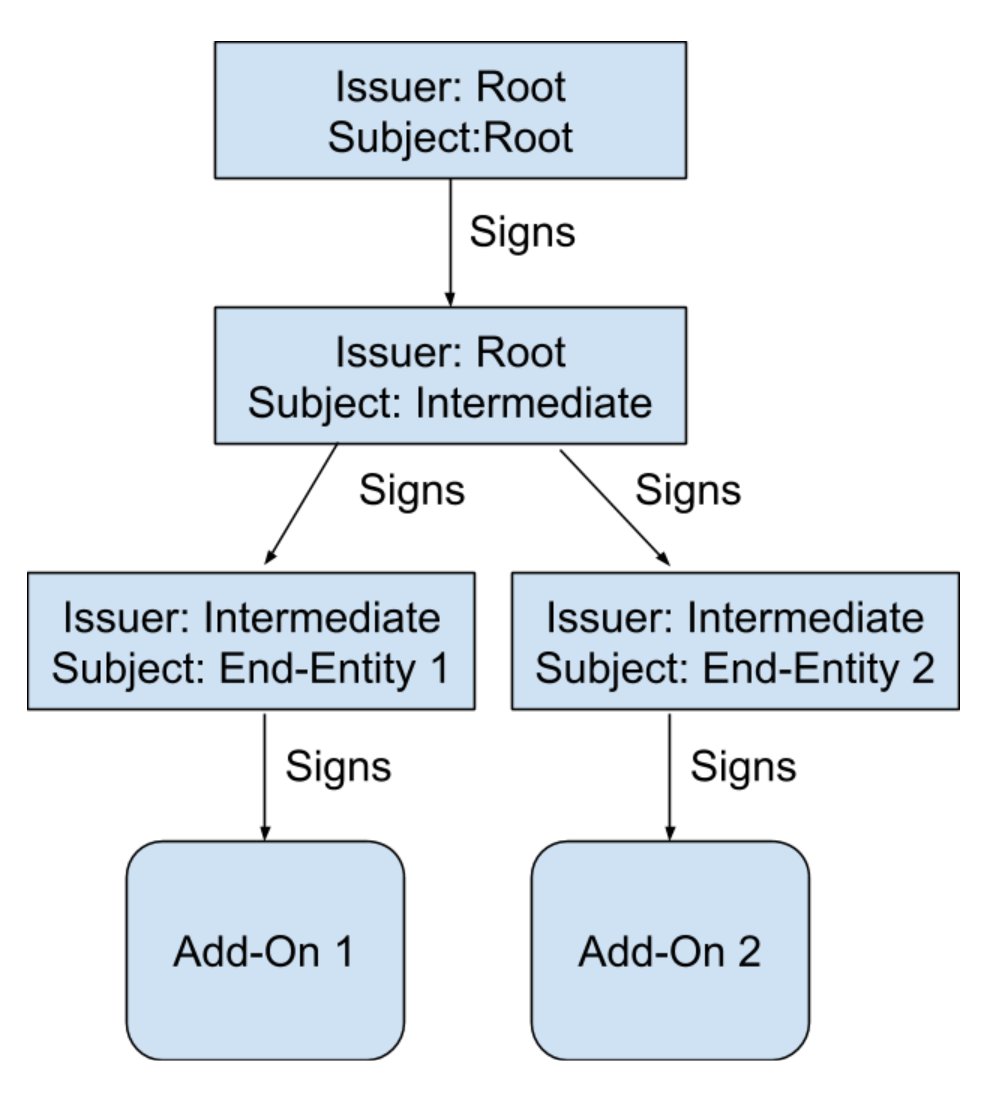

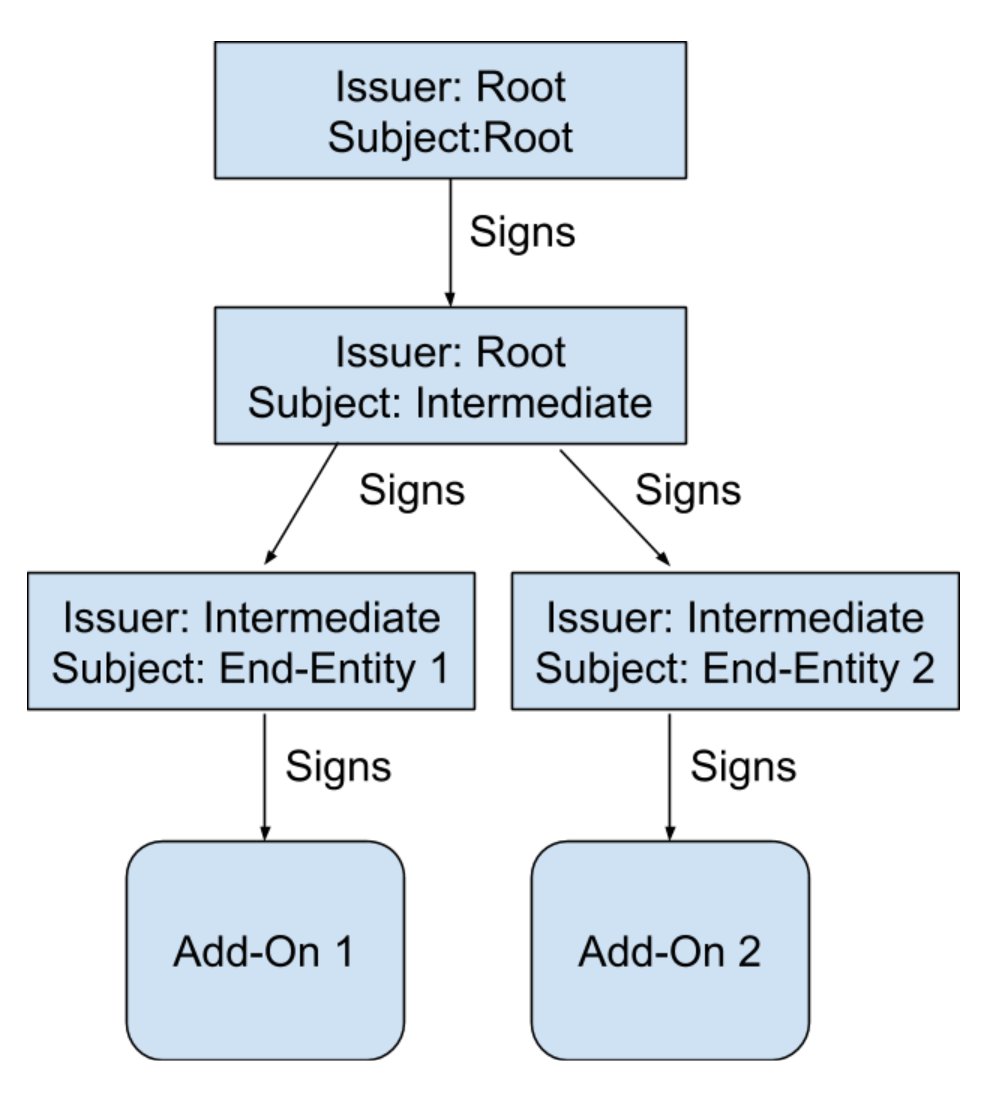

The signature works through the pre-installed Firefox root certificate. It is stored offline in a hardware security module (HSM) . Every few years, it is used to sign a new “intermediate certificate”, which is stored online and used in the signing process. When the extension is submitted for signing, we generate a new temporary “end-entity certificate” and sign it with an intermediate certificate. The end-entity certificate is then used to sign the extension. Visually, it looks like this:

Note that each certificate has a “subject” (to which the certificate belongs) and a “publisher” (signer). In the case of a root certificate, this is the same thing, but for other certificates, the publisher is the entity that signed it.

The important point here is that each addition is signed by its own end-entity certificate, but almost all add-ons have the same intermediate certificate (several very old add-ons were signed by another intermediate link). This is where the problem arose: each certificate has a fixed expiration date. Before or after this window, the certificate will not be accepted, and the extension signed with this certificate cannot be downloaded to Firefox. Unfortunately, the intermediate certificate that we used expired on May 4 after 1:00 UTC, and immediately every addition that was signed by this certificate became unverifiable and could not be uploaded to Firefox.

Although the duration of all supplements expired at about one in the morning, the consequences were not immediately felt. The reason is that Firefox does not constantly check add-ons for validity. They are checked approximately every 24 hours, and the check time is different for each user. As a result, some people experienced problems immediately, some much later. We in Mozilla first found out about the problem around 6:00 pm PST on Friday, May 3, and immediately put together a team to correct the situation.

As soon as we understood what we were facing, we took several steps to avoid worsening the situation.

First, we turned off the signing of new additions. At that moment it was reasonable, because the signature put an invalid certificate. Looking back, it seems that it was possible to leave this function, but it turned out that it also conflicts with the softening of the “hard date firmware”, which we will discuss below (although in the end we did not use it). Therefore, it is good that we have kept this option. So, the signing of new additions is now postponed.

Secondly, we immediately released a quick fix, which suppresses the repeated verification of extension signatures. The idea was to protect users who have not yet been retested. We did this before we had any other fix, and now we removed it when fixes are available.

Theoretically, the solution to such a problem looks simple: make a new, valid certificate and reissue each addition with this certificate. Unfortunately, we quickly determined that this would not work for a number of reasons:

Instead, we focused on trying to develop a fix that would correct the situation with little or no manual intervention from users.

Having considered a number of approaches, we quickly agreed on two main strategies that we pursued in parallel:

We were not sure what exactly would work, so we decided to work in parallel and implement the first one, which will be similar to a working solution. At the end of the day, we completed the second patch patch - a new certificate, which I will describe in more detail.

As mentioned above, two main steps needed to be performed here:

To understand why this works, you need to know a little more about how Firefox checks add-ons. The add-on itself comes in the form of a batch of files that includes the certificate chain used to sign it. As a result, the addon is independently checked if the root certificate is known, which is configured in Firefox during the build. However, as I said, the intermediate certificate was broken, so the supplement was not really verifiable.

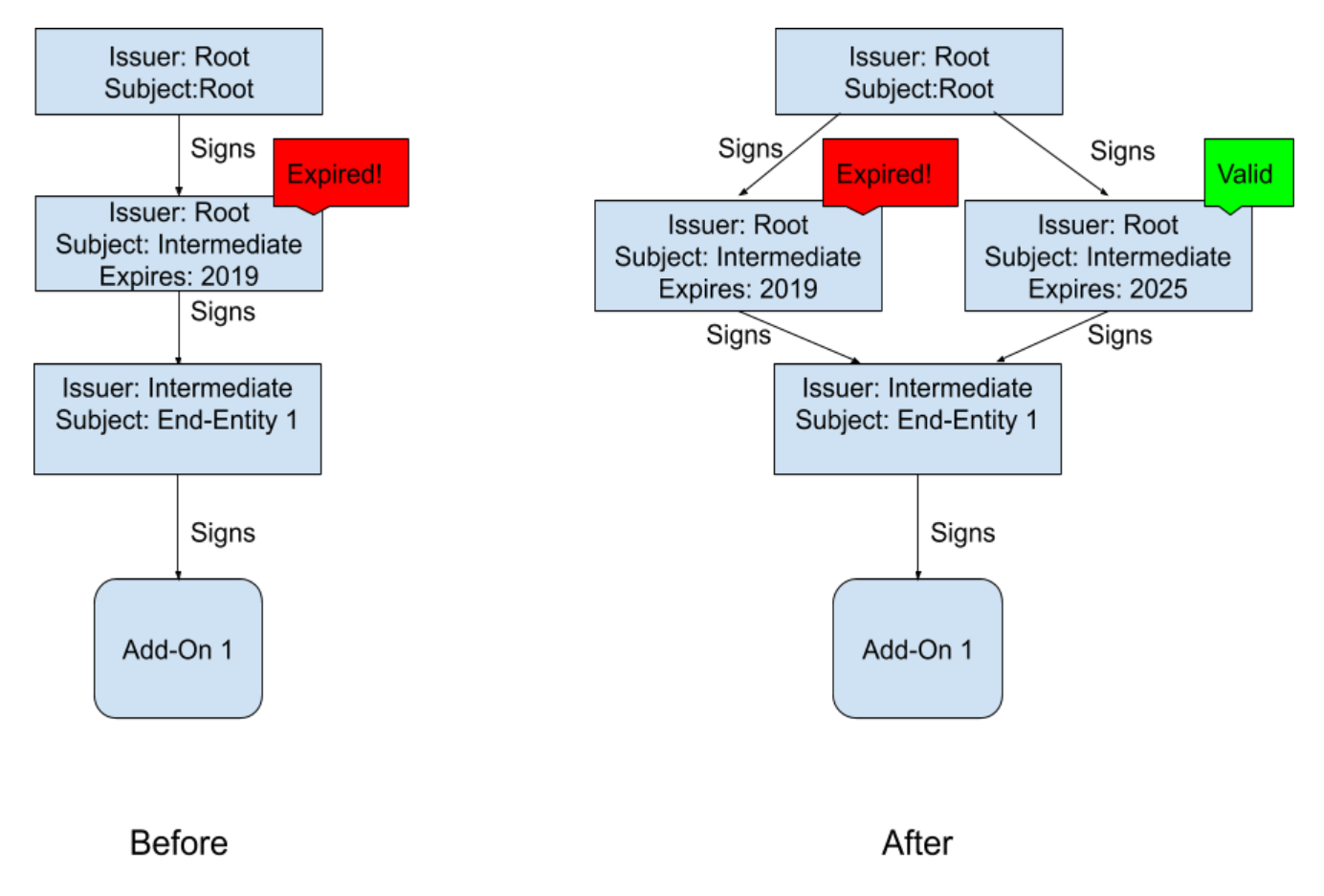

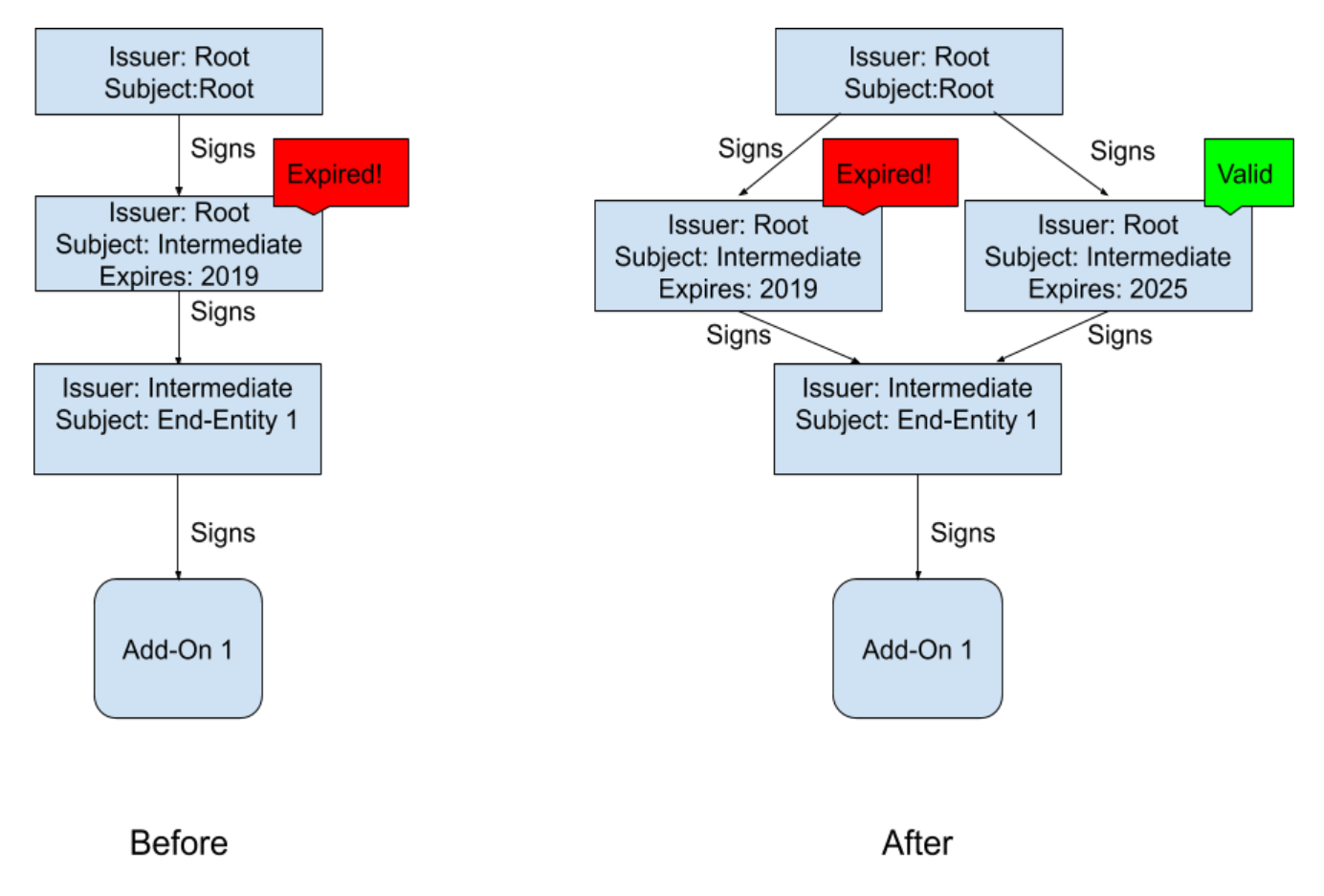

But it turns out that when Firefox tries to verify an extension, it is not limited to using only certificates in the extension itself. Instead, it tries to create a valid certificate chain, starting with the target object certificate and continuing to the root directory. The algorithm is complicated, but at a high level you start with a target object certificate, and then find a certificate whose subject is equal to the publisher of the target object certificate (i.e. intermediate certificate). In the simple case, it is only an intermediate that comes with the add-in, but it can be any certificate that the browser knows about. If we can remotely add a new, valid certificate, Firefox will also try to build such a chain. The figure below shows the situation before and after installing a new certificate.

After installing a new certificate, Firefox has two options for checking the certificate chain: use the old invalid certificate (which does not work) or use the new valid certificate (which will work). The important feature here is that the new certificate has the same subject name and public key as the old certificate, so its signature on the target object certificate is valid. Fortunately, Firefox is smart enough to try both ways until it finds a working one, so the extension becomes valid again. Please note that this is the same logic that we use to verify TLS certificates, so this is a relatively well-understood code that we could use (readers familiar with WebPKI will understand that cross certification works this way).

The great thing about this fix is that it does not require changing any existing extensions. When we install a new certificate in Firefox, even extensions with old certificates will be tested. The trick to delivering a new certificate in Firefox is to do it automatically and remotely, and then force Firefox to double-check all extensions that may have been disabled.

Ironically, the solution was a special type of extension called system add-on (SAO). For studies of the audience (Studies), we have previously developed a system called Normandy, which is able to deliver SAO to Firefox users. These SAOs are automatically executed in the user's browser. Although they are usually used for experiments, they also have wide access to the internal APIs in Firefox. In this case, it is important that they add new certificates to the certificate database, which Firefox uses to check the extensions (technical note: we don’t add a certificate with any special privileges; it gets its privileges by signing with a root certificate. We just add it in the pool of certificates that can be used by Firefox. Thus, we do not add a new privileged certificate in Firefox).

So the solution here is to create a SAO that does two things:

But wait, you say. Add-ons don't work, how do you make SAO work? Well, we will sign it with a new certificate!

So, now we have a plan: to issue a new certificate to replace the old one, to build a system addition, to install it in Firefox, and to deploy it in Normandy. We started work at about 6:00 pm PST on Friday, May 3, and sent a correction to Normandy at about 2:44 am, that is, less than 9 hours, and then it took another 6-12 hours before most users received it. In fact, this is a very good start, but I saw on Twitter a number of questions why we could not make it faster. There are a number of steps that take a lot of time.

First, it took some time to issue a new intermediate certificate. As I mentioned above, the root certificate is in a hardware security module that is stored offline. This is a good security practice, as you rarely use a root certificate and therefore want to keep it safe. But obviously, it is somewhat inconvenient when you need to issue a new certificate in an emergency. In any case, one of our engineers had to go to a safe place where the HSM is stored. Then there were several false starts when we could not issue the correct certificate, and each attempt was worth an hour or two of testing before we knew exactly what to do.

Secondly, the development of the system takes some time. Conceptually, everything is very simple, but even simple programs require some caution, and we really wanted to make sure that we did not worsen the situation. And before shipping, SAO had to test it, and it takes time, especially considering that it needs to be signed. But the signature system was turned off, so we had to look for workarounds.

Finally, as soon as the SAO was ready for shipment, it took time to deploy. Firefox clients check Normandy updates every 6 hours, and, of course, many clients are offline, so the update distribution to all Firefox users did not go instantly. However, at the moment most have received an update and / or a new release, which we released later.

Although the system addon, deployed through the System of Studies, should correct the situation for most users, it did not reach everyone. In particular, several types of users require a different approach:

We can’t do anything with the last group - they will have to upgrade to the new version of Firefox, because the old versions usually have quite serious unpatched security vulnerabilities. We know that some people stayed on older versions of Firefox because they want to run old-style extensions, but many of them now work with newer versions of Firefox. For other groups, we have developed a patch for Firefox that will install the new certificate after the update. It is also released as a new version of Firefox "with a dot", so people should get it - and, probably, have already received it - through a regular update channel. If you have a build from a downstream, you need to wait for an update from the maintainer.

We acknowledge that none of this is perfect. In particular, in some cases, users lose data associated with add-ons (for example, an extension of the type “containers with multiple accounts” ).

We have not been able to develop a patch that will avoid this side effect, but we believe that in the short term, this is the best approach for most users. In the long term, we will look for the best architectural approaches to solve such problems.

First, I want to say that the team here did an amazing job: they developed and sent a correction in less than 12 hours from the time of the initial report. As a person who attended the meeting, where it happened, I can say that people worked incredibly hard in a difficult situation and that very little time was wasted.

With that said, it is obvious that this is not an ideal situation, and this should not happen at all. We clearly need to adjust our processes to reduce the likelihood of this and similar incidents and facilitate their correction.

Next week we will conduct a formal debriefing and publish a list of changes that we intend to make, but for now, here are my initial thoughts on this matter. Most importantly, we should have a much better way to track the status of all systems in Firefox that are a potential time bomb. You need to make sure that none of them suddenly stop working. We are still working on the details here, but, at a minimum, we need to make an inventory of such systems.

Secondly, we need a mechanism to quickly roll updates to users, even when — especially when — everything else does not work. It's great that we were able to use the Studies system, but this was also not the most advanced tool that we put into operation, and which had some unwanted side effects. In particular, we know that many users have automatic updates enabled, but they would prefer not to participate in research, and this is a reasonable preference (yes, to say, I set up my browser this way!), But at the same time we should be able to push updates. Whatever the internal technical mechanisms, users should be able to select updates (including fixes), but discard everything else. In addition, the update channel should work faster. Even on Monday, we still have users who did not take away the patch or the new release, which is clearly not ideal. This problem has already been worked on, but this incident shows how important it is.

Finally, we will look more generally at our extension security architecture to make sure that it provides security correctly with minimal risk of disruption.

Next week we will publish the results of a more thorough analysis of this situation.

Recently, an incident occurred in Firefox, when most add-ons (extensions, add-ons) stopped working. This is due to an error on our part: we did not notice that one of the certificates, which is used to sign additions, has expired, which led to the disconnection of the vast majority of them. Now that we have fixed the problem, and most of the additions have been repaired, I would like to tell you in detail what happened, why, and how we fixed everything.

For reference: extensions and their signature

Although many use Firefox out of the box, the browser also supports a powerful extension mechanism. They add third-party features to Firefox that extend the features we offer by default. Currently, there are more than 15,000 Firefox add-ons: from ad blocking to managing hundreds of tabs .

Firefox requires that all installed add-ons are digitally signed . This requirement is intended to protect users from malicious extensions, requiring a minimum standard of verification by Mozilla staff. Before we introduced this requirement in 2015, we had serious problems with malicious extensions.

')

The signature works through the pre-installed Firefox root certificate. It is stored offline in a hardware security module (HSM) . Every few years, it is used to sign a new “intermediate certificate”, which is stored online and used in the signing process. When the extension is submitted for signing, we generate a new temporary “end-entity certificate” and sign it with an intermediate certificate. The end-entity certificate is then used to sign the extension. Visually, it looks like this:

Note that each certificate has a “subject” (to which the certificate belongs) and a “publisher” (signer). In the case of a root certificate, this is the same thing, but for other certificates, the publisher is the entity that signed it.

The important point here is that each addition is signed by its own end-entity certificate, but almost all add-ons have the same intermediate certificate (several very old add-ons were signed by another intermediate link). This is where the problem arose: each certificate has a fixed expiration date. Before or after this window, the certificate will not be accepted, and the extension signed with this certificate cannot be downloaded to Firefox. Unfortunately, the intermediate certificate that we used expired on May 4 after 1:00 UTC, and immediately every addition that was signed by this certificate became unverifiable and could not be uploaded to Firefox.

Although the duration of all supplements expired at about one in the morning, the consequences were not immediately felt. The reason is that Firefox does not constantly check add-ons for validity. They are checked approximately every 24 hours, and the check time is different for each user. As a result, some people experienced problems immediately, some much later. We in Mozilla first found out about the problem around 6:00 pm PST on Friday, May 3, and immediately put together a team to correct the situation.

Damage Restriction

As soon as we understood what we were facing, we took several steps to avoid worsening the situation.

First, we turned off the signing of new additions. At that moment it was reasonable, because the signature put an invalid certificate. Looking back, it seems that it was possible to leave this function, but it turned out that it also conflicts with the softening of the “hard date firmware”, which we will discuss below (although in the end we did not use it). Therefore, it is good that we have kept this option. So, the signing of new additions is now postponed.

Secondly, we immediately released a quick fix, which suppresses the repeated verification of extension signatures. The idea was to protect users who have not yet been retested. We did this before we had any other fix, and now we removed it when fixes are available.

Parallel work

Theoretically, the solution to such a problem looks simple: make a new, valid certificate and reissue each addition with this certificate. Unfortunately, we quickly determined that this would not work for a number of reasons:

- There are a lot of extensions (more than 15,000), and the service is not optimized for mass signing, so simply re-signing each add-on will take longer than we wanted.

- After the add-ons are signed, users will need to get a new add-on. Some are hosted on Mozilla servers, and Firefox will update them within 24 hours, but users will have to manually update any add-ons that are installed from other sources, which is very inconvenient.

Instead, we focused on trying to develop a fix that would correct the situation with little or no manual intervention from users.

Having considered a number of approaches, we quickly agreed on two main strategies that we pursued in parallel:

- Firefox patch to change the date used to verify the certificate. In this case, the existing add-ons will magically work again, but the delivery of the new Firefox assembly will be required.

- Generate a new valid certificate and somehow convince Firefox to accept it instead of the existing, expired one.

We were not sure what exactly would work, so we decided to work in parallel and implement the first one, which will be similar to a working solution. At the end of the day, we completed the second patch patch - a new certificate, which I will describe in more detail.

Certificate of Replacement

As mentioned above, two main steps needed to be performed here:

- Create a new valid certificate.

- Remotely install it in Firefox.

To understand why this works, you need to know a little more about how Firefox checks add-ons. The add-on itself comes in the form of a batch of files that includes the certificate chain used to sign it. As a result, the addon is independently checked if the root certificate is known, which is configured in Firefox during the build. However, as I said, the intermediate certificate was broken, so the supplement was not really verifiable.

But it turns out that when Firefox tries to verify an extension, it is not limited to using only certificates in the extension itself. Instead, it tries to create a valid certificate chain, starting with the target object certificate and continuing to the root directory. The algorithm is complicated, but at a high level you start with a target object certificate, and then find a certificate whose subject is equal to the publisher of the target object certificate (i.e. intermediate certificate). In the simple case, it is only an intermediate that comes with the add-in, but it can be any certificate that the browser knows about. If we can remotely add a new, valid certificate, Firefox will also try to build such a chain. The figure below shows the situation before and after installing a new certificate.

After installing a new certificate, Firefox has two options for checking the certificate chain: use the old invalid certificate (which does not work) or use the new valid certificate (which will work). The important feature here is that the new certificate has the same subject name and public key as the old certificate, so its signature on the target object certificate is valid. Fortunately, Firefox is smart enough to try both ways until it finds a working one, so the extension becomes valid again. Please note that this is the same logic that we use to verify TLS certificates, so this is a relatively well-understood code that we could use (readers familiar with WebPKI will understand that cross certification works this way).

The great thing about this fix is that it does not require changing any existing extensions. When we install a new certificate in Firefox, even extensions with old certificates will be tested. The trick to delivering a new certificate in Firefox is to do it automatically and remotely, and then force Firefox to double-check all extensions that may have been disabled.

Normandy and research system

Ironically, the solution was a special type of extension called system add-on (SAO). For studies of the audience (Studies), we have previously developed a system called Normandy, which is able to deliver SAO to Firefox users. These SAOs are automatically executed in the user's browser. Although they are usually used for experiments, they also have wide access to the internal APIs in Firefox. In this case, it is important that they add new certificates to the certificate database, which Firefox uses to check the extensions (technical note: we don’t add a certificate with any special privileges; it gets its privileges by signing with a root certificate. We just add it in the pool of certificates that can be used by Firefox. Thus, we do not add a new privileged certificate in Firefox).

So the solution here is to create a SAO that does two things:

- Installs a new certificate that we did.

- Causes the browser to re-check each add-on to activate those that have disabled.

But wait, you say. Add-ons don't work, how do you make SAO work? Well, we will sign it with a new certificate!

Putting it all together ... and why so long?

So, now we have a plan: to issue a new certificate to replace the old one, to build a system addition, to install it in Firefox, and to deploy it in Normandy. We started work at about 6:00 pm PST on Friday, May 3, and sent a correction to Normandy at about 2:44 am, that is, less than 9 hours, and then it took another 6-12 hours before most users received it. In fact, this is a very good start, but I saw on Twitter a number of questions why we could not make it faster. There are a number of steps that take a lot of time.

First, it took some time to issue a new intermediate certificate. As I mentioned above, the root certificate is in a hardware security module that is stored offline. This is a good security practice, as you rarely use a root certificate and therefore want to keep it safe. But obviously, it is somewhat inconvenient when you need to issue a new certificate in an emergency. In any case, one of our engineers had to go to a safe place where the HSM is stored. Then there were several false starts when we could not issue the correct certificate, and each attempt was worth an hour or two of testing before we knew exactly what to do.

Secondly, the development of the system takes some time. Conceptually, everything is very simple, but even simple programs require some caution, and we really wanted to make sure that we did not worsen the situation. And before shipping, SAO had to test it, and it takes time, especially considering that it needs to be signed. But the signature system was turned off, so we had to look for workarounds.

Finally, as soon as the SAO was ready for shipment, it took time to deploy. Firefox clients check Normandy updates every 6 hours, and, of course, many clients are offline, so the update distribution to all Firefox users did not go instantly. However, at the moment most have received an update and / or a new release, which we released later.

Last steps

Although the system addon, deployed through the System of Studies, should correct the situation for most users, it did not reach everyone. In particular, several types of users require a different approach:

- Users who have disabled telemetry or research.

- Firefox users for Android (Fennec), where we have no research.

- Users of subsequent Firefox ESR builds who do not subscribe to telemetry reports.

- Users who are behind HTTPS MiTM-proxies, because our add-on installation systems enforce keys for these connections, which conflicts with proxies.

- Users of very old Firefox builds that the Studies system cannot reach.

We can’t do anything with the last group - they will have to upgrade to the new version of Firefox, because the old versions usually have quite serious unpatched security vulnerabilities. We know that some people stayed on older versions of Firefox because they want to run old-style extensions, but many of them now work with newer versions of Firefox. For other groups, we have developed a patch for Firefox that will install the new certificate after the update. It is also released as a new version of Firefox "with a dot", so people should get it - and, probably, have already received it - through a regular update channel. If you have a build from a downstream, you need to wait for an update from the maintainer.

We acknowledge that none of this is perfect. In particular, in some cases, users lose data associated with add-ons (for example, an extension of the type “containers with multiple accounts” ).

We have not been able to develop a patch that will avoid this side effect, but we believe that in the short term, this is the best approach for most users. In the long term, we will look for the best architectural approaches to solve such problems.

Lessons

First, I want to say that the team here did an amazing job: they developed and sent a correction in less than 12 hours from the time of the initial report. As a person who attended the meeting, where it happened, I can say that people worked incredibly hard in a difficult situation and that very little time was wasted.

With that said, it is obvious that this is not an ideal situation, and this should not happen at all. We clearly need to adjust our processes to reduce the likelihood of this and similar incidents and facilitate their correction.

Next week we will conduct a formal debriefing and publish a list of changes that we intend to make, but for now, here are my initial thoughts on this matter. Most importantly, we should have a much better way to track the status of all systems in Firefox that are a potential time bomb. You need to make sure that none of them suddenly stop working. We are still working on the details here, but, at a minimum, we need to make an inventory of such systems.

Secondly, we need a mechanism to quickly roll updates to users, even when — especially when — everything else does not work. It's great that we were able to use the Studies system, but this was also not the most advanced tool that we put into operation, and which had some unwanted side effects. In particular, we know that many users have automatic updates enabled, but they would prefer not to participate in research, and this is a reasonable preference (yes, to say, I set up my browser this way!), But at the same time we should be able to push updates. Whatever the internal technical mechanisms, users should be able to select updates (including fixes), but discard everything else. In addition, the update channel should work faster. Even on Monday, we still have users who did not take away the patch or the new release, which is clearly not ideal. This problem has already been worked on, but this incident shows how important it is.

Finally, we will look more generally at our extension security architecture to make sure that it provides security correctly with minimal risk of disruption.

Next week we will publish the results of a more thorough analysis of this situation.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/451220/

All Articles