Mathematical duet mapped an infinite area of minimal surfaces

A pair of mathematicians, based on a little-known mathematical theory of 30 years ago, demonstrated that minimal surfaces, resembling a soap film, appear in large numbers on a wide range of figures

In late 2011, Brian White occasionally heard a knock at the door of his Stanford office. Two young mathematicians, Fernando Coda Marquez and Andre Nevis , were waiting for him at these moments, who always had about the same question: wouldn’t White have a few minutes to help them understand one of the obscure parts of the little-known dissertation by several hundred pages written thirty years ago?

In the thesis, written by John Pitts , was presented a powerful mechanism for constructing minimal surfaces - structures similar to soap film and bubbles - inside a wide range of figures. When it is possible to construct a minimal surface in a figure, the latter makes it possible to study the geometry of the surrounding space. Such surfaces appear in various scientific problems, from the study of black holes to the development of biomolecules.

And yet, all these years, Pitts's dissertation fell out of the attention of scientists - perhaps because it was incredibly difficult to read. Marquez and Nevis were convinced that there was a lot of potential in it. “It was obvious to us that this theory was completely underestimated and went unnoticed,” said Nevis, who now works as a professor at the University of Chicago.

')

Although White never asked this couple why they were interested in the work of Pitts, they each time stated that their interest was “purely academic,” Nevis said. However, they had a definite goal - to prove Wilmore's hypothesis 50 years ago, where the question of finding the best possible form of donut is being considered (more details later). After three months of struggling with ideas from Pitts’s dissertation, Marquez and Nevis achieved their goal , earning many awards and positive reviews.

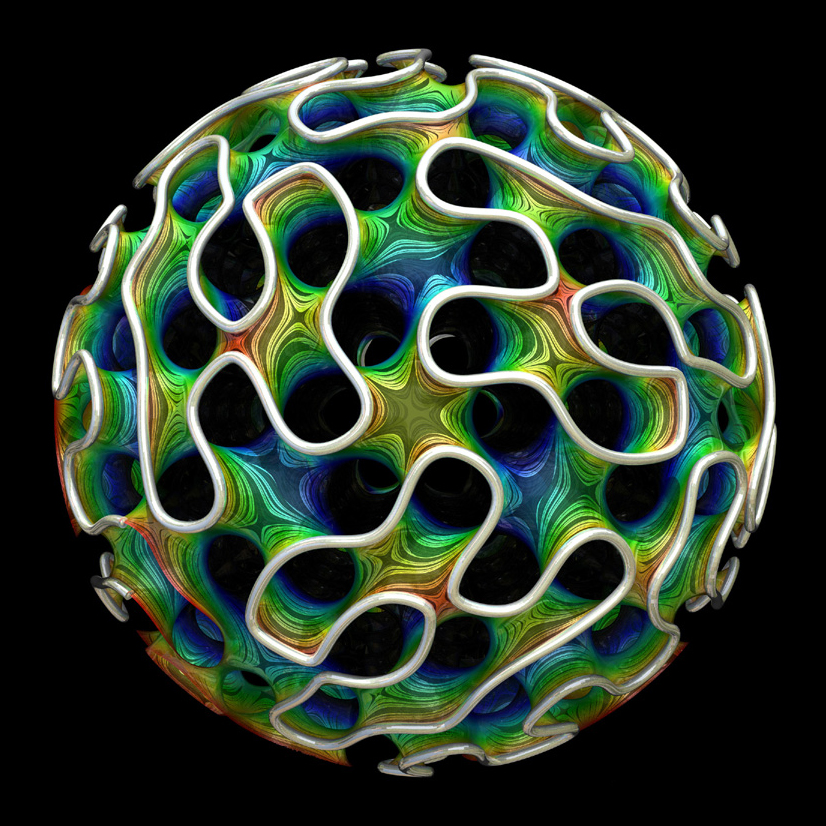

But in the past few years they have been able to push Pitts’s ideas much further. The pitts, with their curator, Frederick Almgren, have found a way to ensure that each shape has at least one minimum surface in a small number of dimensions. Now Marquez and Nevis, with the help of a cohort of young mathematicians gathered around them, based on the ideas of Almgren and Pitts, showed that in general these forms should contain a multitude of minimal surfaces — infinitely many surfaces crowded and crushed around all the corners of the figures. “This is a huge breakthrough,” Karen Uhlenbeck, a well-known geometer from the University of Texas, wrote to us in an email.

“It’s a lot of effort to create a single minimal surface,” said Richard Shoen of the University of California, Irvine, who consulted Nevis about 15 years ago. “The fact that there are so many of them is an amazing fact.”

This renaissance of the theory of Almgren and Pitts led to an explosion of activity in the last couple of years. "The results appear so fast and in such large numbers that it is difficult to keep track of them," said White. “It seems to me very interesting and wonderful.”

Marking up the mountain range

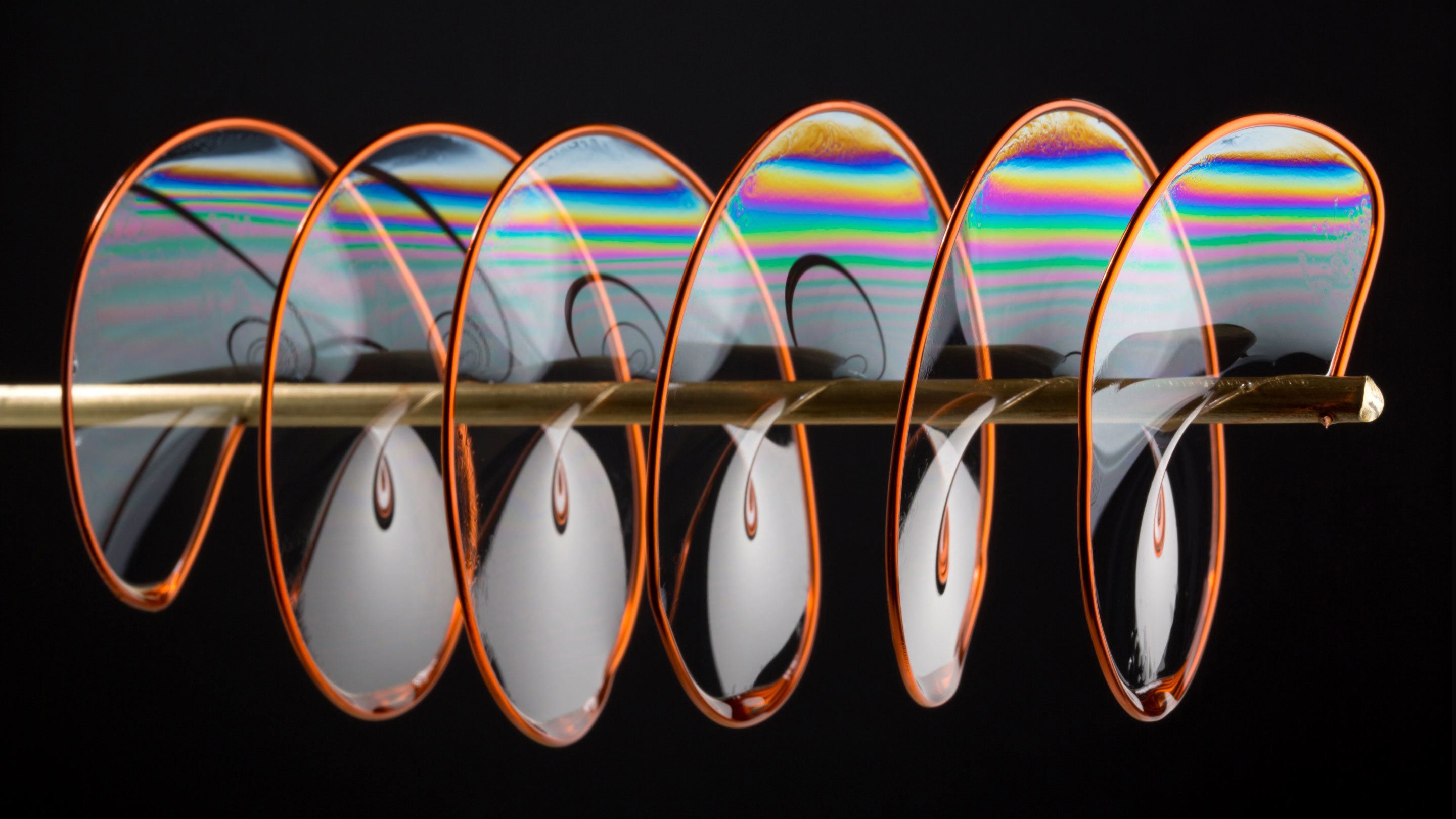

Dip the twisted wire in a soap solution, or blow a soap bubble, and the liquid will quickly form the surface of the smallest possible area. The geometry of these minimal surfaces took mathematicians hundreds of years. They appear in various areas, from architecture, where minimal surface inspires the design of roofs and other structures, to the creation of microparticles for drug delivery. Five years ago, when a team of scientists created porous molecules capable of carrying drugs or hormones within them, they discovered that some molecules took the form of a gyroid , an infinitely repeating surface, some parts of which resemble a soap film.

Technically, mathematicians consider surfaces with a minimal surface only soap films on a wire, but not soap bubbles, because in an abstract space where there are no air molecules, the bubble would blow to the point. However, the film on the wire does not fully satisfy the mathematicians. Its inside is a smooth surface, but the wire breaks off sharply. It is logical to think about whether it is possible to extend this surface beyond the limits of the wire borders so that it continues to look like a soap film on every single section. Sometimes it is possible, and the surface stretches to infinity. Sometimes the surface comes back and awkwardly intersects with itself, or encounters other difficulties.

Gyroid - a minimal surface type that arose during the design of microparticles for drug delivery

In ordinary space, this exhausts all possibilities. But mathematicians and other scientists often consider other worlds that are different from the usual infinite three-dimensional space for us - curved or finite, such as three-dimensional analogies of a sphere or a torus surface. Such figures have new interesting possibilities: minimal surfaces that are bent on themselves and closed in a closed final figure that does not require wire support.

In the theory of relativity, these finite minimal surfaces play the role of the event horizon of black holes. And if they can be found on any shape, it helps the mathematicians to consider their geometry from different angles: they provide a pattern for cutting the shape (or variety ) into potentially simpler pieces, they point to areas of positive curvature within the diversity - into sections, curving inward, like a sphere or a black hole, as opposed to curving outward.

“We know little about varieties with positive curvature,” said Shoin.

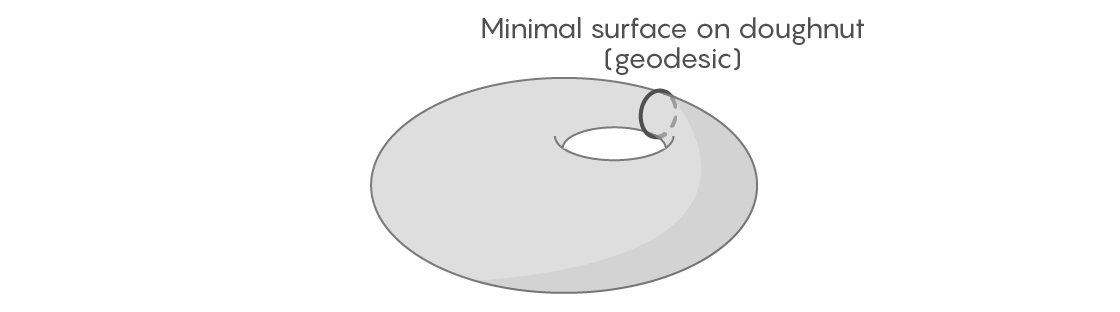

However, it is often difficult to prove the existence of a minimal surface within a figure. To understand why, consider the two-dimensional version of this problem. The question of finding the minimum surface makes sense in any dimension: mathematicians simply consider the surface to be a form whose measurement is one less than the space in which it lives. So, in a two-dimensional world, the minimum surface will be “geodesic” curves composed of the shortest paths connecting nearby points.

For some two-dimensional figures, it is easy to find geodesic curves that are closed into a finite loop. Take the surface of the torus - even not necessarily smooth and symmetric, let it have irregularities and convexities. If we wrap such a donut with a rubber band passing through its center, we can imagine how much we tighten it and shift it to different possible positions. One of them will be the shortest - it will be a geodesic curve by definition.

But if our figure is a sphere, this approach no longer works. On a perfectly flat sphere, the geodesic curve is easy to find - it will be the equator and other full circles. But on an uneven sphere, for example, on the surface of the Earth, it is not clear where the geodesic curves go, and whether some of them close in a loop. You can imagine how we wrap the Earth with a rubber band, as in the case of a donut. But if you start moving it, trying to shorten it, it will shrink to one point, because unlike a donut, the sphere has no hole for which the elastic band would cling.

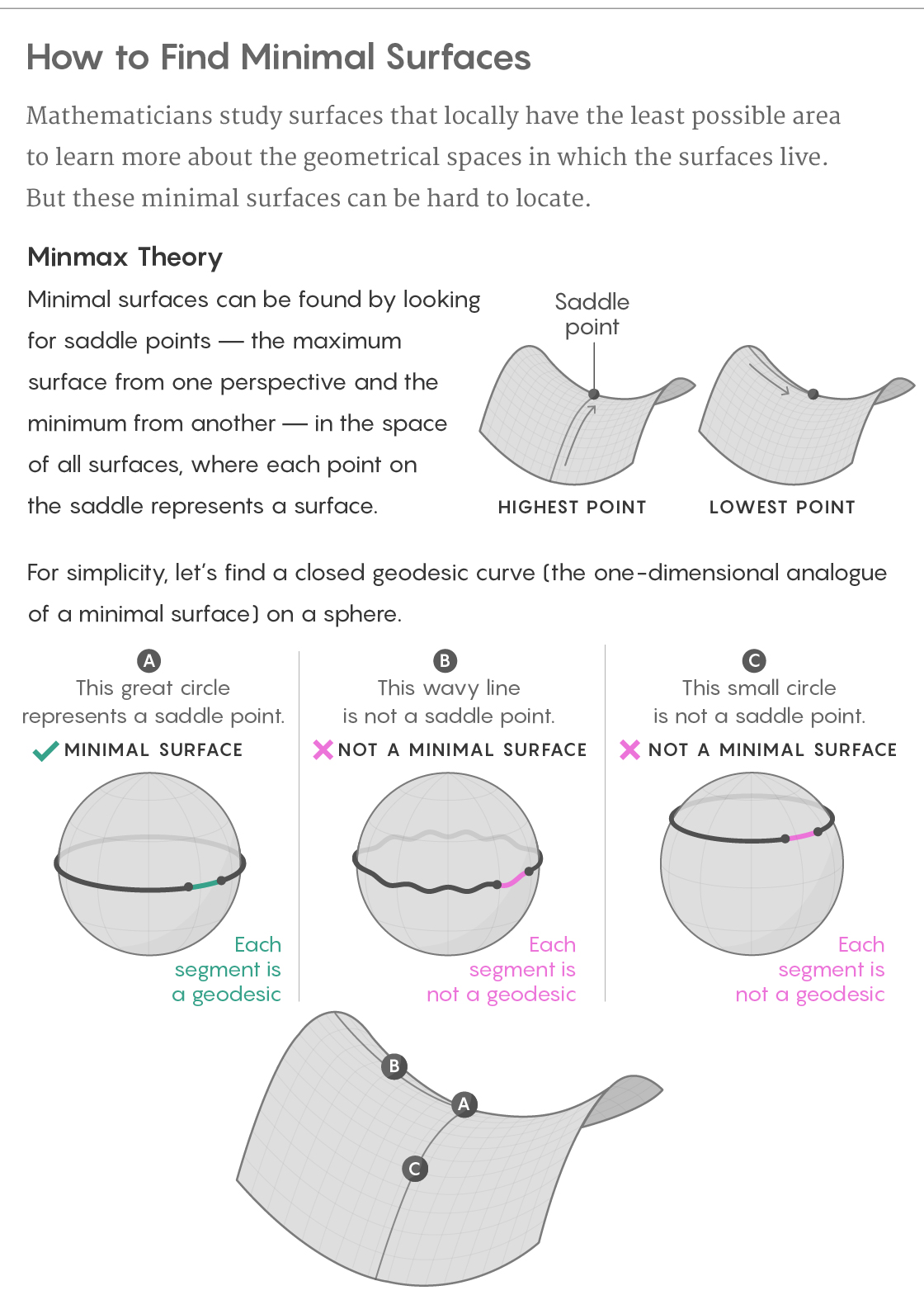

However, this fiasco with a rubber band harbors the germ of success. If the equator of a circular sphere is intercepted by a rubber band, then the only way to move it - add waves to it - will make it longer. If you move it differently, up or down to a new latitude, it will become shorter. Therefore, the equator from one point of view will be the shortest curve, and on the other - the longest.

This makes the equator related to the saddle of a mountain pass, the highest point on one side (from the path through the mountains) and the lowest on the other (from the path through the nearby peaks). And this is not just a weak analogy: as a rule, minimal surfaces turn out to be such saddles, but their mountain ranges live in a world that is much harder to visualize.

Defining the minimal surfaces of a figure, we can consider a new world consisting of all possible finite surfaces that exist inside this figure - let's call it “surface space”. Each point of the surface space corresponds to the entire surface entirely on the original figure. Then we can consider the area of each surface as the height of the corresponding point in the surface space, with the result that our world will have a natural topography. Finding minimal surfaces on the original shape becomes a search for saddles in the surface space.

In 1917, George David Birkhoff used this approach to show that any sphere, hilly or smooth, always has one closed geodesic curve. Approximately six decades later, Almgren and Pitts masterfully extended Birkhoff's ideas, marking the topography of the surface space on all the final figures in the dimensions from three to seven, and then used this topography to prove that such figures always have at least one minimal closed surface. Pitts ’1981 dissertation on this Minmax theory — so named because the saddle is both a minimum point and a maximum point — was“ absolutely amazing, ”Nevis said.

However, it was also extremely difficult. Few people understood the nuances of the theory, and some who studied its mathematicians claimed that it was not fully confirmed, Shoin said. “I don’t think there was any doubt that it was extremely interesting and important,” he said. “But it was unclear how complete it is.”

Work on the theory of minmaks gradually faded away. “Pitts’s work has been forgotten by the mathematical community for about 30 years,” said Nevis. She was not resurrected until Nevis and Marquez met in 2006 in the elevator of the mathematical building at Princeton University.

Through the mountain pass

At that moment, Marquez arrived at Princeton for a lecture; Nevis got a job there soon after defending a doctoral degree. Both had a native language Portuguese (Marquez was originally from Brazil, and Nevis was from Portugal), and they easily found a common language. “Then I spoke with him for the first time, but he talked with me as if we were already friends for 10 years,” recalls Marquez, who now works as a professor at Princeton.

Then they found that it turns out that it is just as natural for them to discuss mathematical ideas. They have different styles: Marquez is calmer, and Nevis is more stressful. But it was a plus for them. “You rarely find a person who complements you so well,” said Marquez.

Both were eager to find some complicated math problem that they could dive into. For several years, a couple of ideas were redeployed every time their paths crossed, “to see what lingers,” said Nevis. "We had a million ideas, and in the end one of them was filtered out and turned into something formed."

The filtered problem turned out to be the famous “Wilmore's hypothesis” problem. She suggests finding a torus shape that minimizes a value known as Wilmore's energy, which, roughly speaking, measures the difference between a given figure and a round sphere. In 1965, Wilmore suggested that this would be the most round donut of a particularly symmetrical form, known as Clifford's torus , but despite the many attempts that were made, no one could prove the hypothesis.

Marquez (left) and Nevis

Marquez and Nevis developed a promising approach, but in order for it to work, they needed the last ingredient: the minimax theory. They thought it would take two or three weeks to master this theory and write the final work - until Pitts’s book was opened. “We were shocked - what is it all about? Said Nevis. “The book was incredibly dry.”

Individual theorems grew into many pages - and this was only a description of the theorems, not their proof. The main theorem was just hard to find. “I remember how Fernando came to my office and said: I found the statement of the theorem!” Said Nevis.

Thor Clifford

When they got stuck, they made pokerface and asked for help from White, one of the few people who understood most of Pitts’s work (although White himself described these conversations as “blind, leading blind”; Pitts himself, a professor at Texas A & M University, graduated write work on the theory of Minmax several decades ago). “We were incredibly motivated, and so we were able to get through,” recalls Nevis. “But this was not a task for the faint of heart.”

By the time Marquez and Nevis had completed their proof of Wilmore’s hypothesis, they understood Minmax theory better than any other mathematician. They were convinced that its potential extends much further than the very statement of the hypothesis. “We knew that we have a very powerful theory,” said Nevis. - Each time, using the method to prove a certain result that has remained open for a long time, you understand that there is something in it. This suggests that you should continue to dig further. "

The Minmaks scheme from Almgren and Pitts produces not just one saddle, but an infinite number of them. In theory, this should correspond to an infinite number of minimal surfaces of the original form. But Almgren and Pitts could not show that the minimum surfaces obtained in this way were different. Therefore, the only thing that could definitely be said was that each figure had at least one minimal surface.

After that, “the development of the topic has practically stopped,” said Nevis. “It was the best result for a period of more than 30 years.”

A new ingredient was required, and Marquez and Nevis found it. An endless list of minmax surfaces, as they showed in 2016, behaves in the same way as the frequencies at the drum.

The mathematician Hermann Weil in 1911 showed that the fundamental frequencies of a drum have one unexpected property: roughly speaking, high frequencies depend only on the volume of the drum, and not on its shape. Marquez and Nevis, together with Evgeny Lekumovich from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, showed that minmax surfaces satisfy a mathematical law similar to the law of drum frequencies. In particular, the areas of surfaces are roughly determined by the amount of space in which they live, and not by its shape.

This result, which put an end to the hypothesis put forward a few decades ago, allowed Marquez and Nevis in 2017 to show - this time they were helped by Kay Aire from the University of Tokyo - that for most figures the list of minmaks contains an infinite number of different minimum surfaces. Moreover, they showed that these surfaces are "dense": they appear next to each point of the surrounding space. The intuition that supports this conclusion is that in order for the volume of space to determine the areas of finding the minimal surfaces, the latter must somehow “see” the entire volume as a whole. And this “suggests that these guys are in all their diversity,” said Marquez.

A couple of months later, this couple, along with Marquez's graduate student, Antoine Sun , showed that if you go through the list of minmax surfaces, it will be seen that they fill space evenly - what mathematicians call "equidistribution."

“When I heard that they were equally distributed, I was amazed,” said White. “It seemed that people should not have been able to prove such a result even during my life.”

In the last couple of years a few more mathematicians joined the question. For example, in January, Xin Zhou from the University of California at Santa Barbara, on the basis of Marquez and Nevis's previous work, proved that for most of the figures, all the minimal surfaces in the Almgren and Pitts list are different, which put a pleasant end to this question. "It really nicely closes this topic, open since Almgren and Pitts work in the 80s," said White.

This family of results takes into account almost every shape in dimensions from three to seven - with the exception of the smoothest forms, however counterintuitive it may be. But last June, Sunn was able to prove that every figure in these dimensions, including the most rounded, has infinitely many closed minimal surfaces, which confirmed another hypothesis by several decades.

It is not yet clear whether the density and the equidistribution will behave in the same uniform manner, and also how much the minmax theory works not in compact manifolds, or in eight or more dimensions (however, the new work has achieved some success here as well). Mathematicians predict that we will be able to get answers to many questions earlier than it seemed.

“Everything is developing extremely fast,” Nevis said. “Every week I look at the site with arxiv preprints, and I see there someone decided something else.”

From one point of view, these works mark the end - or the end - of a story that has been hanging in its incomplete form for almost four decades. But it is also a new beginning: mathematicians are only beginning to understand that these new ideas regarding minimal surfaces will be able to tell us about the spaces in which they live.

“I can fully assume that other interesting ways of applying this knowledge will appear soon, but I’m not sure what it is,” said Shoin. “I am sure that this will be one of the main directions in geometry.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/450018/

All Articles