Antiquities: Philips DCC, Loser Cassette

The Philips Digital Compact Cassette digital cassette went on sale in late 1992, just a few weeks ahead of its main competitor, Sony Minidisc. In 1996, the development of the format was stopped: the remnants of the equipment were sold out, cassettes were produced and sold for several more years. The DCC format has lost out in the fight with both the competitor and over time: the consumer could not be convinced of the advantages of the home digital recording.

This article is a logical continuation of my two ( 1 , 2 ) materials about minidisk. Sony could also stop promoting its rewritable digital audio format due to low sales, but decided to continue. And because the minidisk turned out to be a more developed format, more accessible to collectors, and for many it causes some nostalgia. The DCC has almost none of this. Nevertheless, much effort was invested in the development of the format, and there are enough artifacts of those times to study.

I recently bought a Philips DCC900 tape recorder, the first commercially available 1992 model. Today I’ll talk about impressions, other available versions of devices (and there were surprisingly many), and touch on a topic that has dramatically complicated the life of Philips. The fact is that unlike the MDDD DCC was backward compatible: you can play regular audio tapes on all devices. The difficulties associated with supporting such a severe legacy, it seems to me, have exceeded the advantages of compatibility.

I keep the diary of the collector of old pieces of iron in real time in the Telegram .

')

About the DCC format there is less information available than about the minidisk. Unfortunately, there is no evidence of developers - it would be interesting to know how and why they made these or other decisions. There is a lot of information on repairing devices on the DCC museum channel : but there you will find more likely repair instructions for models available on sale. In June, the museum’s creators are planning a premiere of a documentary film about a digital cassette.

Why did Philips even go the way of storing digital audio data on a magnetic tape? The obvious answer: the same Dutch company created a compact cassette in the sixties. One source mentions talks between Sony and Philips about working together on a digital rewritable media, but for some reason the collaboration of the two companies in the development of the CD in the early eighties was not continued. My guess is that the cassette was chosen as the cheapest possible carrier whose production technologies have already been worked out.

On the left - a digital cassette with a shifted protective shutter, in the normal position completely covering the tape. On the right is a regular cassette.

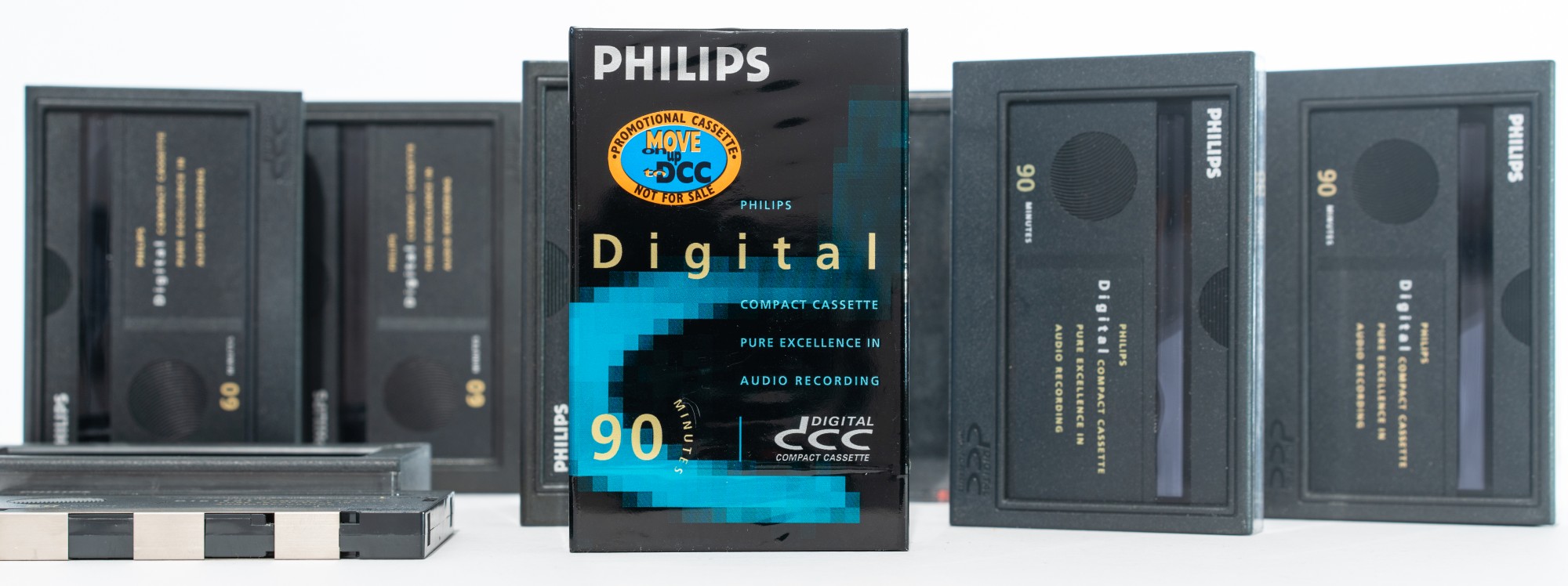

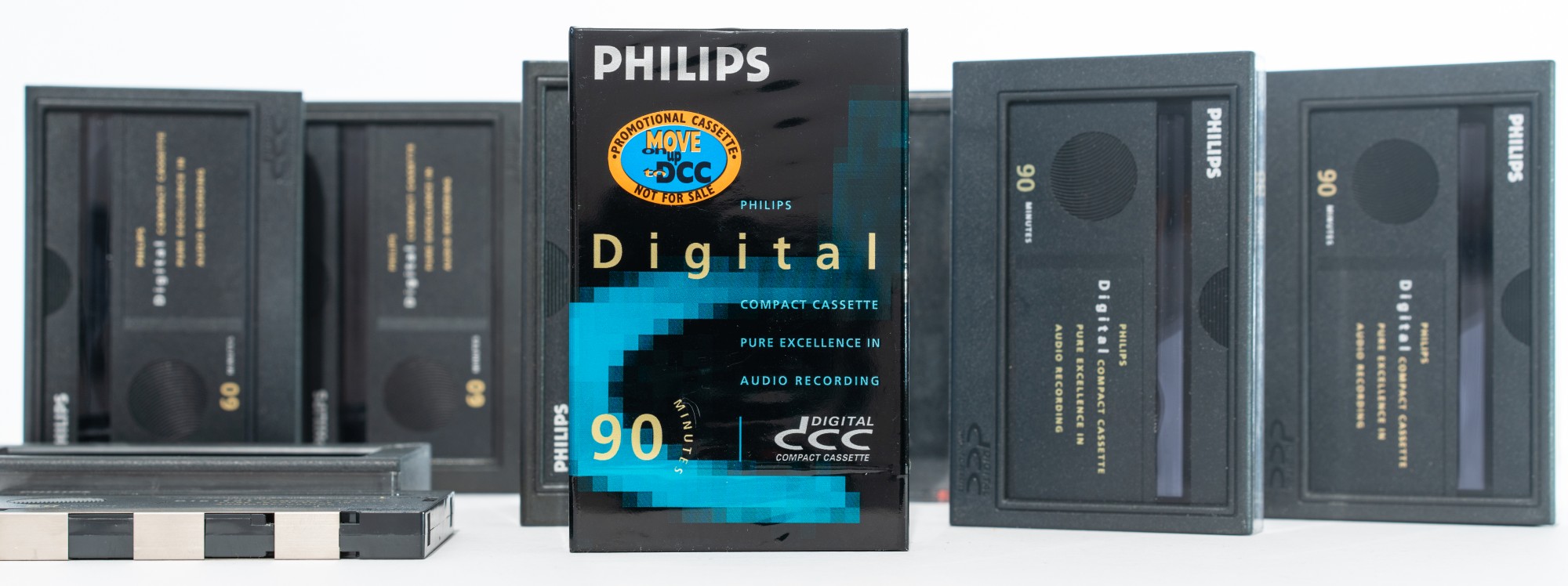

Then I forgot to rewind a regular cassette, you will have to take a word: the chemical composition of the magnetic tape is different from that of a conventional cassette. The tape in the DCC media is either very similar in composition or identical to the tape in video cassettes. In DCC, metal guides are still visible where the magnetic head contacts the tape: together with the counterpart in the tape recorder, they fix the tape relative to the head. Holes for winding the tape are located only on one side of the cassette: automatic reverse is an obligatory feature and it is not necessary to turn the cassette over.

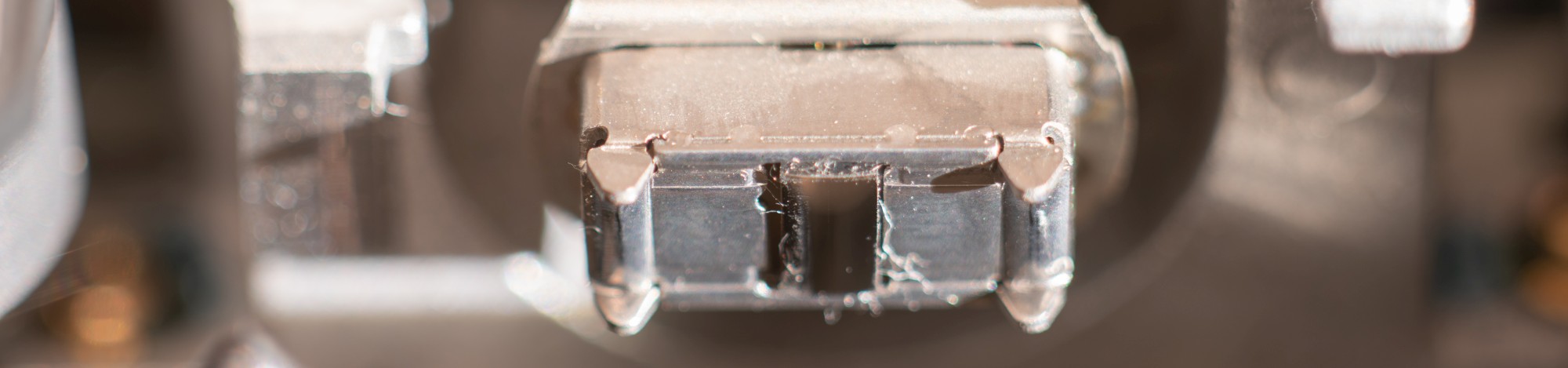

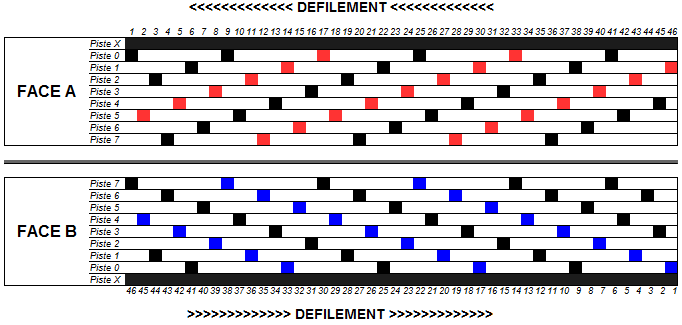

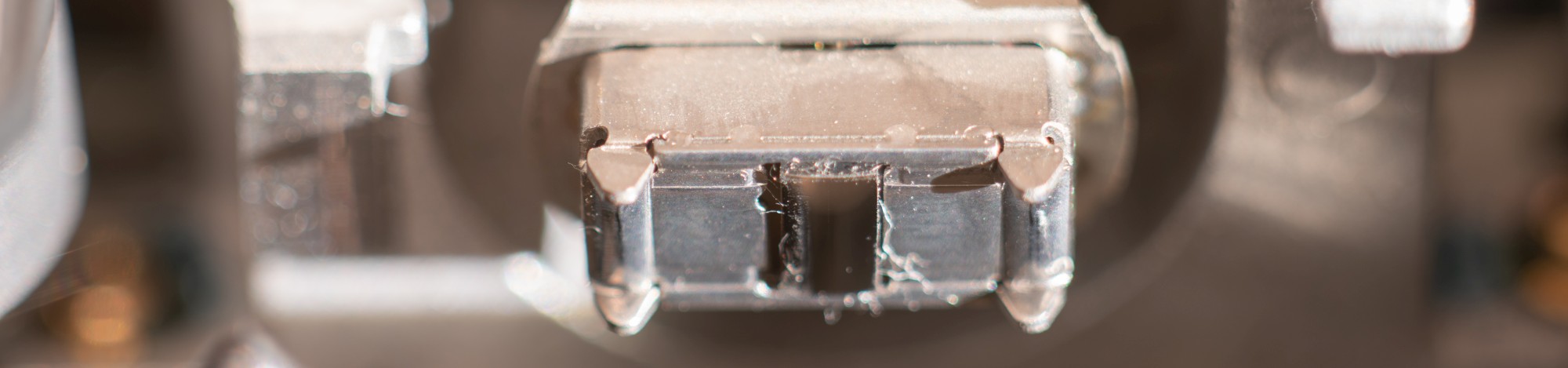

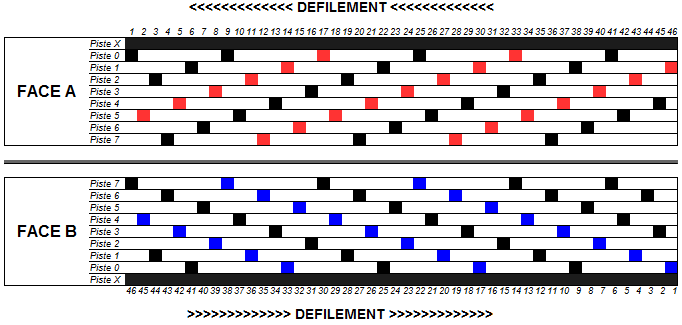

Further difficulties begin. Both the DCC format and the cassette were preceded by the Digital Audio Tape format, which uses a rotating head for reading and writing, as in a VCR. This design made it possible to record more data on the same area of the tape, but it was more difficult and more expensive to implement (and certainly not compatible with old tapes). In the DCC, the data is written onto the tape in several parallel tracks: there are eight of them on each side, plus an additional ninth track for related data — time markers, start identifiers for the new track, and text information.

As a result, the magnetic head for reading and writing is almost the most innovative element of the Philips DCC technology. In my Philips DCC900, the magnetic head is actually a sandwich of 20 heads: 9 for reading, 9 for recording, and two more for reading traditional compact cassettes. In the latest portable devices, the head did not rotate, reading and writing on both sides of the tape was provided with a double set of heads - only forty of them.

Data on the DCC is written in a staggered manner with a bitrate of 768 kilobits per second. Taking into account the data for error correction (it is provided as a tricky distribution of data on tracks, and Eight-To-Fourteen conversion, as in CDs), the actual bitrate is 384 kilobits per second or 260 megabytes for a 90-minute tape. This is slightly more than Minidisc (there were 292 kilobits in the original version of the format). Audio storage, respectively, requires lossy compression. Philips used the minimally modified Mpeg-1 Layer 2 standard, also used on Video CDs, for this purpose. There is a curious article in the magazine Stereophile for April 1991. The correspondent who visited the Philips prototype did not find any differences between the sound of the “squeezed” sound of the digital cassette and the original on the CD. Given that Stereophile has always been and remains a magazine for audiophiles, this is a serious praise. Sony Minidisc first generation compression artifacts were heard even to those who do not have gold ears, and in this sense, Philips gained an advantage.

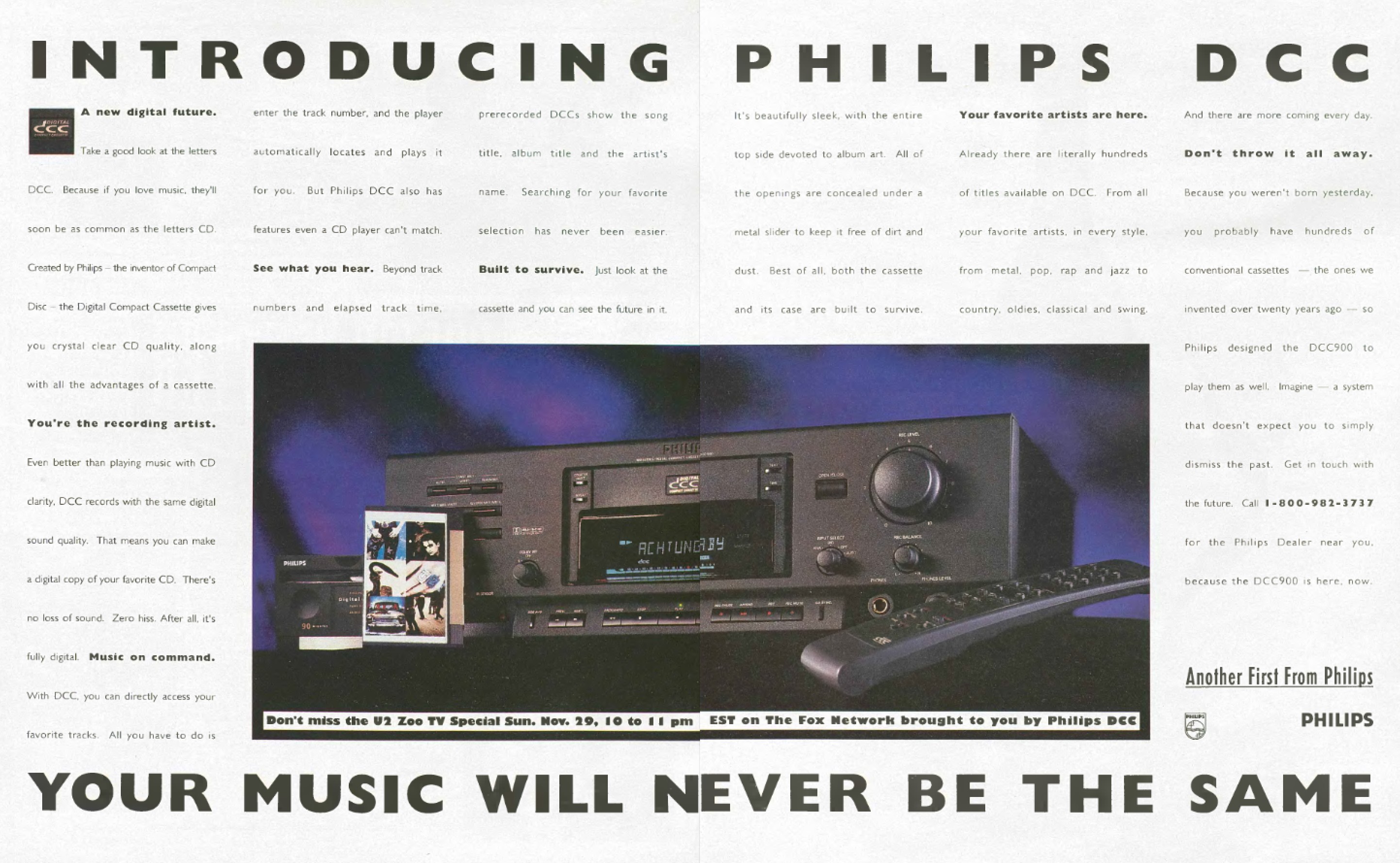

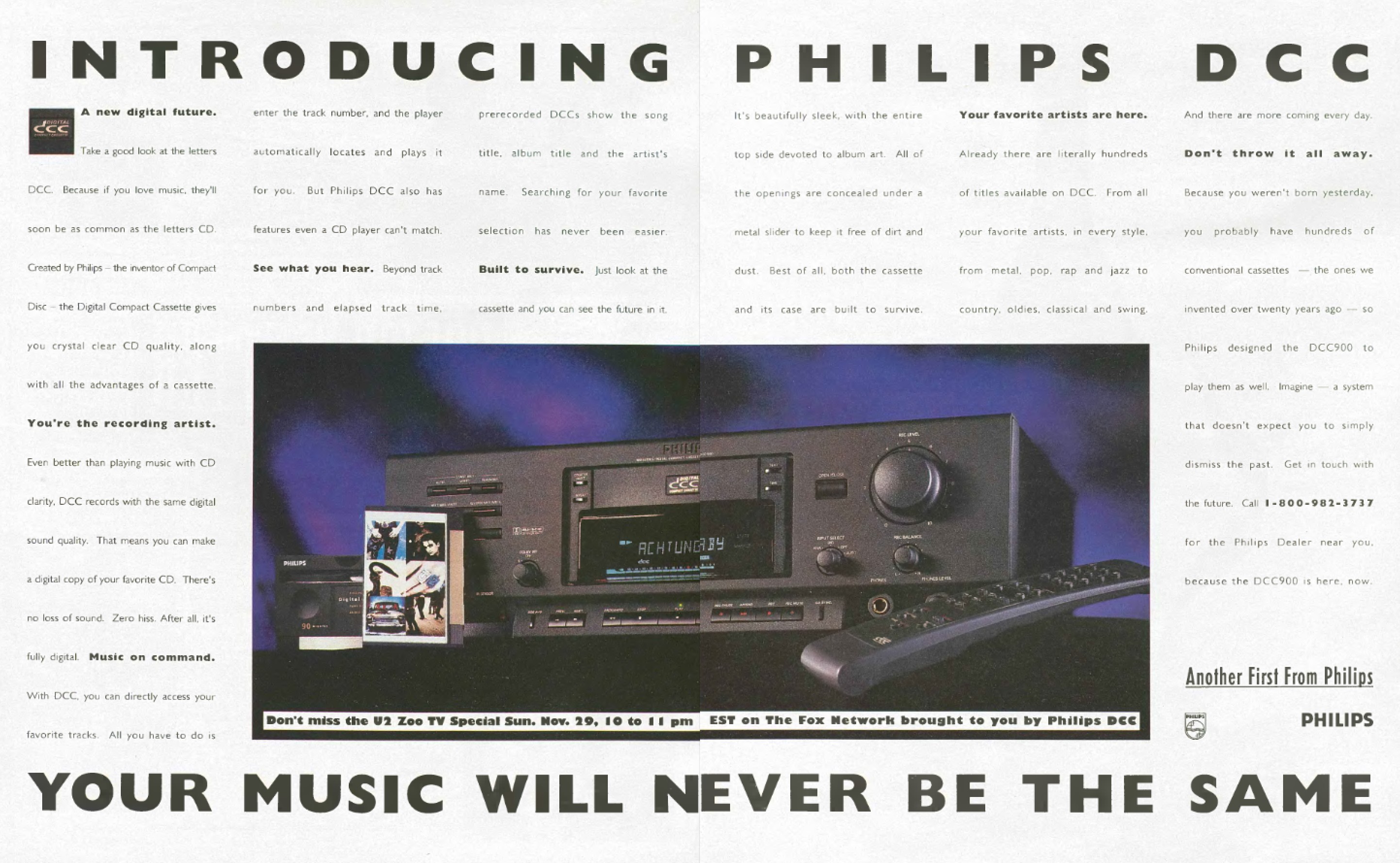

Philips did a lot to advance the format, and it did better than the competitor. Agreements were signed with independent music studios, at the time of the start of sales, an extensive catalog of recorded tapes was immediately available. In music and simply popular editions in the USA of those years, I found DCC advertisements (as in the picture above) more often than minidisc advertisements. Everything seemed to go according to plan. Why did not work? To answer this question, I needed to purchase a live device and experience the format on myself.

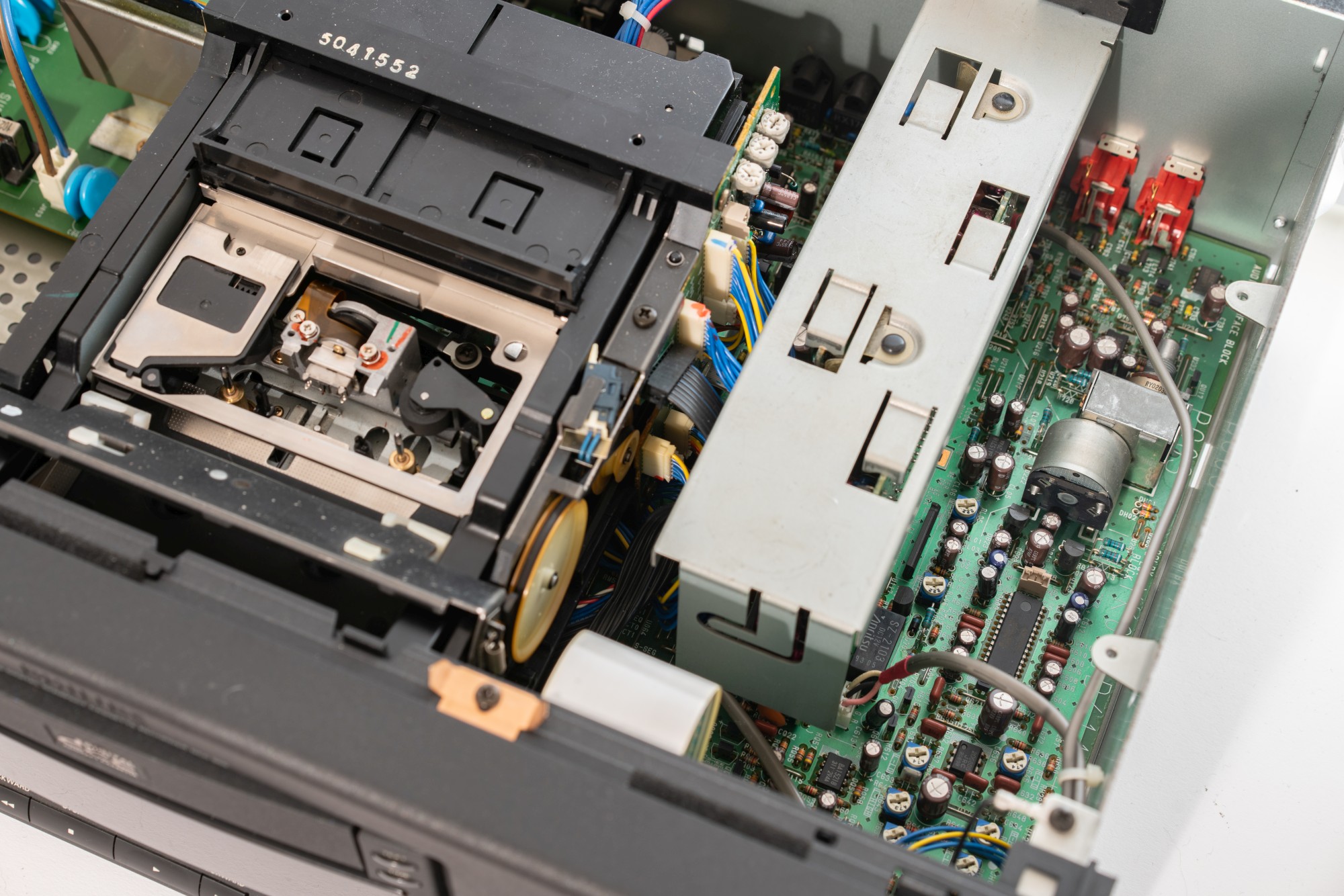

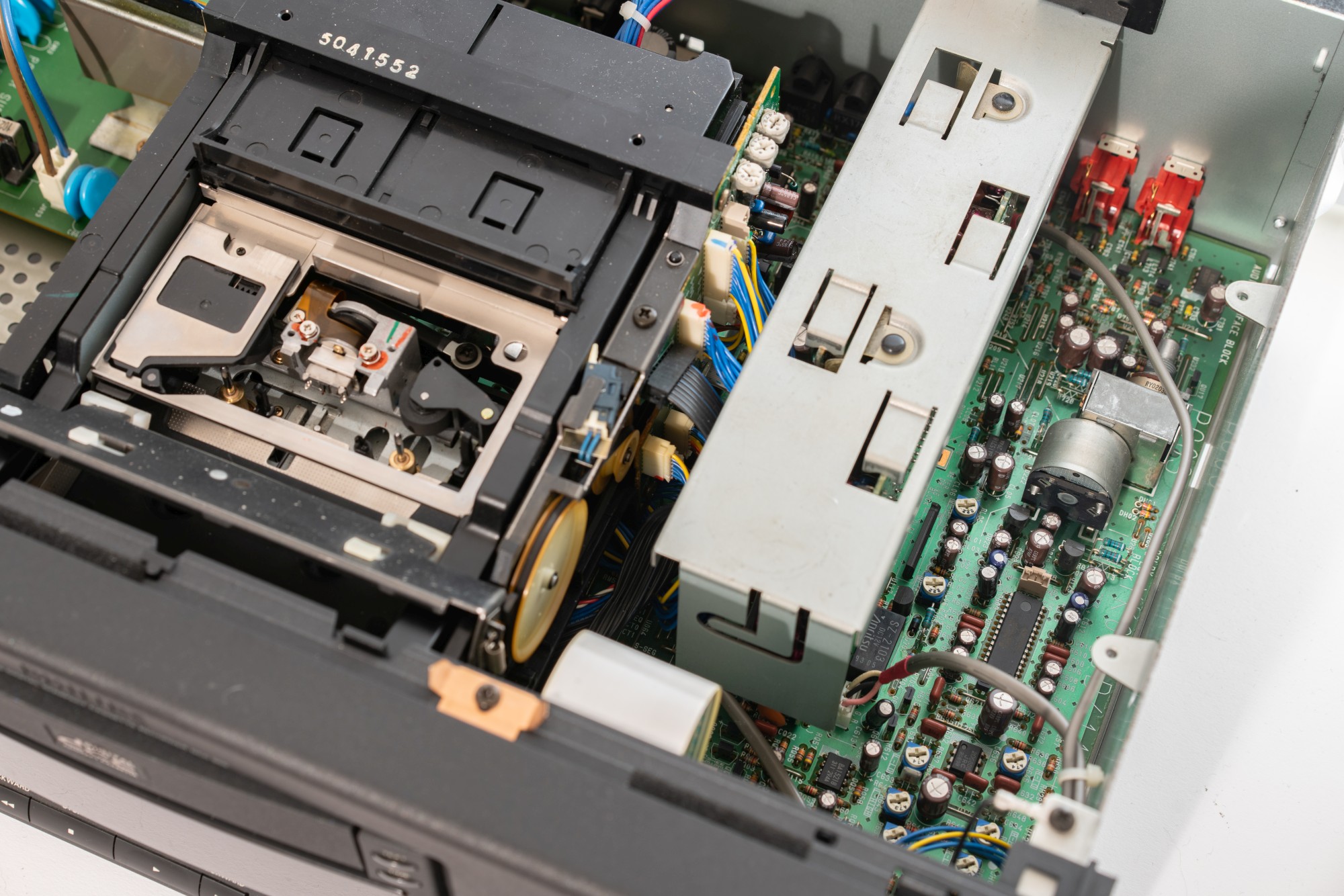

Philips DCC900 was released in 1992, and what a fucking huge it is. Unlike Sony, which immediately relied on portable, portable digital cassette players appeared only in the next year, 1993. For comparison, I put a Kenwood MD on top, but it was made big rather for beauty: inside it is empty enough. But Phillips is not so.

The main board on the bottom is mainly the analog part. The digital is hidden under the metal screen, and two more boards are attached to the cassette mechanism.

Prototypes of Philips DCC tape recorders had a design that provided for vertical mounting of the cassette. Real devices almost all have a slot drive, almost like a CD. The nine-hundredth series of Philips devices in the nineties was the most top-notch: it was possible to assemble a set of CD-player, tuner, amplifier, recorder DCC, and they could all be controlled via a common bus. The price of a digital tape recorder came out rather big - $ 800 in the United States. Cassettes were sold for 8-10 dollars, slightly cheaper than minidisks at the dawn of the format. At some point, the expected savings on cheap media have disappeared somewhere. But digital cassettes could immediately record 90 minutes of music, while the first MDs were 60 minutes.

Okay, let's try to write something down. Like MDD devices, the DCC900 can record from analog and digital inputs. The devices of the first generation could process 16-bit digital sound, in later models the dynamic range was expanded to 18 bits - however, the mini-disc also learned how to do it in 1996. A tape recorder writes a so-called lead-in on an empty tape - essentially a marker indicating that the data starts here. From this point, with further recording on the very ninth data track, the absolute timer begins to be recorded. If the tape already had a recording, the tape recorder searches for an existing marker and, before starting a new recording, reproduces a piece of the old one - what if there is something valuable there? Then everything is simple: we write the sound if we need to stop. The tape recorder always reels the tape so that the next track starts exactly where the previous one ended. If necessary, press the button on the remote control or on the device itself to designate a new track.

Difficulties begin at the end of the tape. Here the developers have provided two options. Where you find that for the first side of the content is enough, you can put one of two markers. In one case, upon seeing the desired marker, the tape recorder stops playback (or recording), winds up the tape to the end, and starts a new track on side B. In the other, the tape recorder instantly switches to the second side. This option leads to the loss of several meters of tape both on the one hand and on the other, but switching between tracks on different sides is as fast as possible (but there is still a delay). Compare this to the minidisc - there is basically no such problem.

I have long wanted to buy the same album on different media. Albums on DCC are rare now: the cassette on the left cost me 10 times more than the cassette on the right, or CD .

The first generation of tape recorders did not know how to write on the tape the names of the tracks, the name of the artist and the name of the album. Generally, if you insert a handwritten cassette into the DCC900, it only shows the absolute time during playback. The track number will be displayed when you reach the nearest marker. Therefore, cassettes with music from the store are the only way to evaluate the format in all its beauty: here is the text information (there was even a record of the text of the songs in the plans), and, most importantly, the data on all the tracks were continuously recorded on the data track. At any time, you can choose any track on the album, and the tape recorder will rewind the tape itself and, if necessary, switch between the parties. Again, the advantage of the minidisc is obvious: it has a table of contents where you can record all the information and, if necessary, edit it without changing the actual recording.

All this cassette slowness was normal in the analog era, but compared to the CD, the DCC standard was seriously losing. Want to switch to a new track? Wait. Want to erase an existing marker? First find it, then erase it. If 10 tracks were recorded on a cassette, and then a part was overwritten again, it was necessary to activate a separate feature that scrolled the entire tape in search of markers and changed the track numbers, if necessary.

Part of the shortcomings of the tape recorders of the first generation were corrected in devices released later. In the second generation, the cassette mechanism was completely reworked: the carrier was now inserted sideways. They released portable players: they weighed half a kilo, worked from a proprietary battery and did not know how to record. In the third generation devices, the jambs were fixed. The last stationary Philips DCC951 tape recorder could rewind the tape from beginning to end in a minute, supported 18-bit sound, allowed to enter the names of tracks and an album.

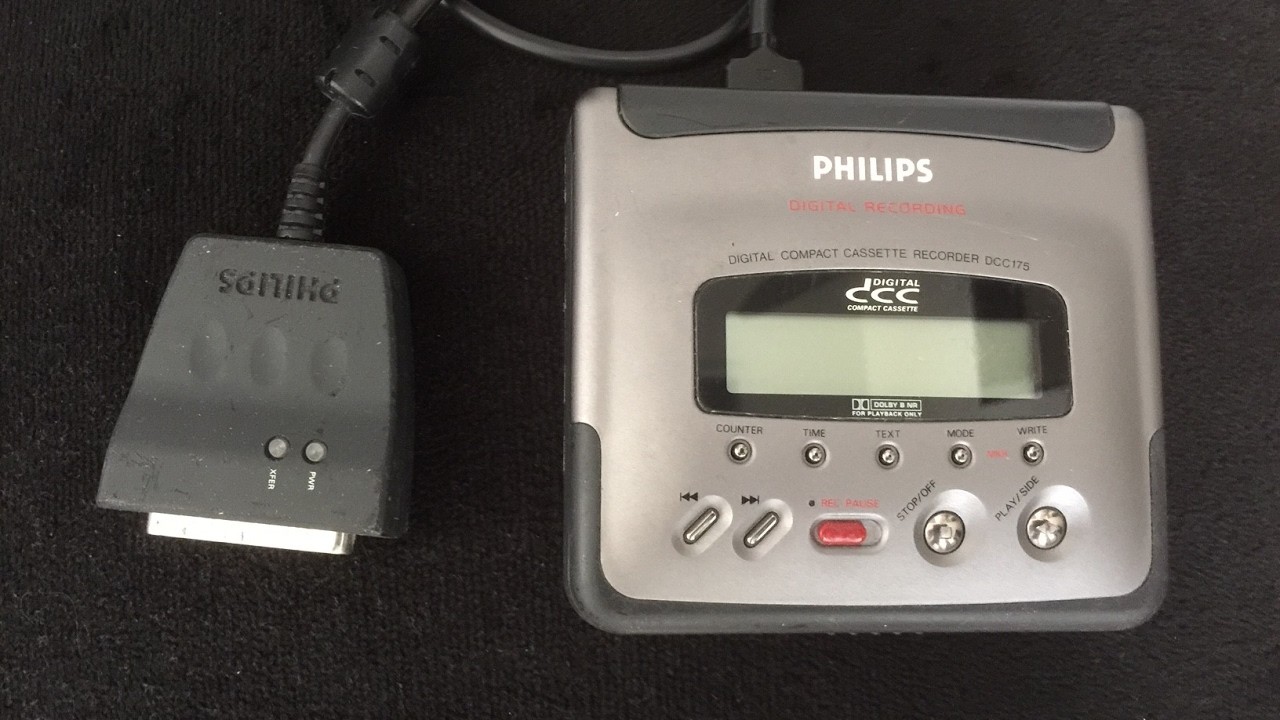

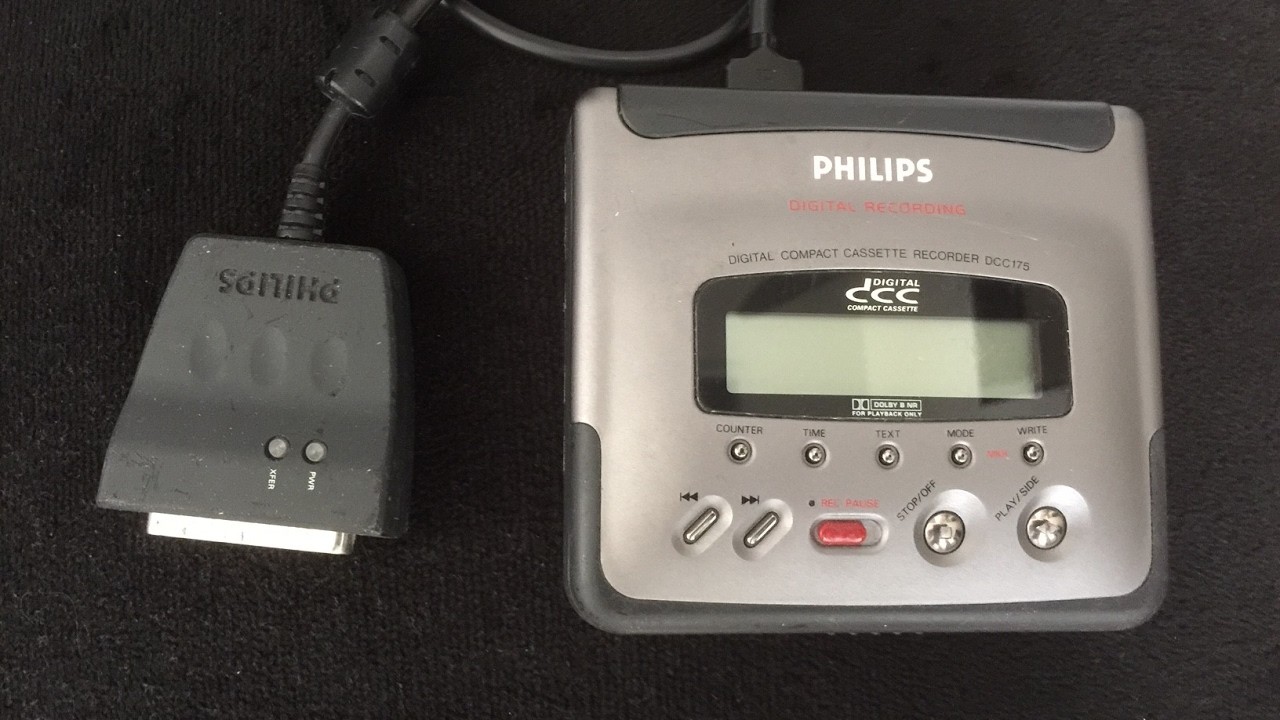

The Philips Philips DCC170 and 175 portable players were relatively compact, supporting recording, including from digital sources. The most interesting portable model Philips DCC175. Using an optional cable, it could be connected via a parallel port to a computer. The software supported Windows 3.1 and Windows 95. It was possible to write data to the cassette (250 megabytes per 90-minute medium), and music, moreover with track names and navigation. Unlike Sony, Philips didn’t worry about protecting the data compression format — it was already half open. Modern releases on DCC cassettes (a couple of albums released last year) are written on a modified version of the DCC175.

Unfortunately, this is the most difficult to collect artifact. Portable players, developed and manufactured not by Philips, but by the Japanese partner Matsushita, were sold a little. And the DCC175 was sold only in the Netherlands, and an optional interface cable to it was generally released in 1000 pieces.

In 2019, I purchased a digital tape recorder, planning to experiment with the format, and to listen to regular audio cassettes. Why? Convenient device with remote control and auto reverse, the most it is for playback, and you can record on another technique. Alas, I didn’t succeed in exploring this use case properly - it’s all about leaky capacitors. On those two boards mounted on the DCC900 mechanism itself, SMD capacitors were used for compactness, which absolutely in all tape recorders of this series flow out over time. I bought the tape recorder as “served”, but alas, the previous owner replaced the capacitors only on the board responsible for the digital signal. The analog path simply does not work normally - the sound of one channel is missing, in the second it is very distorted. We'll have to solder. In general, the minidisk survived the test of time better than the DCC. The reason is the bet on the cassette: in each device it is necessary to replace the drive belts, and in my case also change the capacitors. Finding a minidisc deck in working condition is much easier, and minidisks themselves are generally unkillable. In the early DCC cassettes, the unfortunate material of the pads used to press the tape to the head was used; they not only squeak terribly, but also are not readable properly - the tape moves with jerks.

Why did the format fail? Previously, the main reason was considered competition with Sony. A typical format war has taken place in the home digital audio market, a battle similar to VHS vs. Betamax or Blu-Ray vs. HD DVD. This stage is actually passed almost all data carriers, including even the compact tape, but excluding the CD. One of the two formats was doomed to failure, but now we know that absolutely all physical data carriers were doomed. Both minidisk and DCC lost to cheap CD-R discs and file-sharing networks. Philips did the right thing by fixing the losses, while Sony decided to continue investing in a hopeless format, which, admittedly, was nevertheless more convenient than a digital tape.

In the history of the DCC I am interested in two points. First, was it possible to avoid such a failure and not to invest in the development of a digital cassette at all? Hardly: such complex projects last for many years, and they began in the mid-to-late eighties, when the penny was far away, computers were thin, and the web did not exist at all. At the same time, there is an increase in sales of compact discs, and generally everything is digital, and analog is considered obsolete. It is curious that since then the situation has turned 180 degrees. If you behave cautiously, you can finally give in to the competition and go bankrupt. You want - you do not want, and it is necessary to risk.

Secondly, my familiarity with the DCC shows that legacy support sometimes brings more problems than solutions. I’m already fantasizing here, but in theory, what prevented writing data on a tape in only one direction? Thus, simplifying the mechanism: the auto reverse is not needed, there is no need to invent complicated ways of switching from one side to the other, there is no inevitable pause between tracks. But then backward compatibility would be lost, which marketers relied on. I myself prefer formats or services that maintain compatibility with legacy devices for as long as possible. But the example of a minidisk shows that sometimes it is worth abandoning a heavy legacy and making it really more comfortable and compact.

Finally, the DCC shows that the product may be unsuccessful and leave the stage early, but the technologies underlying it will remain alive. The technology of creating magnetoresistive heads for a digital cassette was borrowed from hard drives, and most likely new developments have found application in the future. Wikipedia mentions an anecdotal example of the use of technology to create heads for DCC tape recorders in beer filters. Both DCC and Minidisk contributed to the development of audio compression with losses at an early stage, and now we indirectly use these developments in listening to music and in wireless transmission to headphones and through the network.

In my case, DCC was the first format that I acquired purely for studying: there could be no nostalgic background here. I decided on this experiment only because of compatibility with a traditional audio cassette. If I manage to change the capacitors, and if the board was not killed by the leaked acid, I will have a backup tape recorder. Fans of digital cassettes (they also exist) do not strongly recommend using these devices in this way - the old cassettes dirty their heads and pressure rollers much faster. But I probably will not listen to their advice. In the end, we only live once.

This article is a logical continuation of my two ( 1 , 2 ) materials about minidisk. Sony could also stop promoting its rewritable digital audio format due to low sales, but decided to continue. And because the minidisk turned out to be a more developed format, more accessible to collectors, and for many it causes some nostalgia. The DCC has almost none of this. Nevertheless, much effort was invested in the development of the format, and there are enough artifacts of those times to study.

I recently bought a Philips DCC900 tape recorder, the first commercially available 1992 model. Today I’ll talk about impressions, other available versions of devices (and there were surprisingly many), and touch on a topic that has dramatically complicated the life of Philips. The fact is that unlike the MDDD DCC was backward compatible: you can play regular audio tapes on all devices. The difficulties associated with supporting such a severe legacy, it seems to me, have exceeded the advantages of compatibility.

I keep the diary of the collector of old pieces of iron in real time in the Telegram .

')

About the DCC format there is less information available than about the minidisk. Unfortunately, there is no evidence of developers - it would be interesting to know how and why they made these or other decisions. There is a lot of information on repairing devices on the DCC museum channel : but there you will find more likely repair instructions for models available on sale. In June, the museum’s creators are planning a premiere of a documentary film about a digital cassette.

Why did Philips even go the way of storing digital audio data on a magnetic tape? The obvious answer: the same Dutch company created a compact cassette in the sixties. One source mentions talks between Sony and Philips about working together on a digital rewritable media, but for some reason the collaboration of the two companies in the development of the CD in the early eighties was not continued. My guess is that the cassette was chosen as the cheapest possible carrier whose production technologies have already been worked out.

On the left - a digital cassette with a shifted protective shutter, in the normal position completely covering the tape. On the right is a regular cassette.

Then I forgot to rewind a regular cassette, you will have to take a word: the chemical composition of the magnetic tape is different from that of a conventional cassette. The tape in the DCC media is either very similar in composition or identical to the tape in video cassettes. In DCC, metal guides are still visible where the magnetic head contacts the tape: together with the counterpart in the tape recorder, they fix the tape relative to the head. Holes for winding the tape are located only on one side of the cassette: automatic reverse is an obligatory feature and it is not necessary to turn the cassette over.

Further difficulties begin. Both the DCC format and the cassette were preceded by the Digital Audio Tape format, which uses a rotating head for reading and writing, as in a VCR. This design made it possible to record more data on the same area of the tape, but it was more difficult and more expensive to implement (and certainly not compatible with old tapes). In the DCC, the data is written onto the tape in several parallel tracks: there are eight of them on each side, plus an additional ninth track for related data — time markers, start identifiers for the new track, and text information.

As a result, the magnetic head for reading and writing is almost the most innovative element of the Philips DCC technology. In my Philips DCC900, the magnetic head is actually a sandwich of 20 heads: 9 for reading, 9 for recording, and two more for reading traditional compact cassettes. In the latest portable devices, the head did not rotate, reading and writing on both sides of the tape was provided with a double set of heads - only forty of them.

Data on the DCC is written in a staggered manner with a bitrate of 768 kilobits per second. Taking into account the data for error correction (it is provided as a tricky distribution of data on tracks, and Eight-To-Fourteen conversion, as in CDs), the actual bitrate is 384 kilobits per second or 260 megabytes for a 90-minute tape. This is slightly more than Minidisc (there were 292 kilobits in the original version of the format). Audio storage, respectively, requires lossy compression. Philips used the minimally modified Mpeg-1 Layer 2 standard, also used on Video CDs, for this purpose. There is a curious article in the magazine Stereophile for April 1991. The correspondent who visited the Philips prototype did not find any differences between the sound of the “squeezed” sound of the digital cassette and the original on the CD. Given that Stereophile has always been and remains a magazine for audiophiles, this is a serious praise. Sony Minidisc first generation compression artifacts were heard even to those who do not have gold ears, and in this sense, Philips gained an advantage.

Philips did a lot to advance the format, and it did better than the competitor. Agreements were signed with independent music studios, at the time of the start of sales, an extensive catalog of recorded tapes was immediately available. In music and simply popular editions in the USA of those years, I found DCC advertisements (as in the picture above) more often than minidisc advertisements. Everything seemed to go according to plan. Why did not work? To answer this question, I needed to purchase a live device and experience the format on myself.

Philips DCC900 was released in 1992, and what a fucking huge it is. Unlike Sony, which immediately relied on portable, portable digital cassette players appeared only in the next year, 1993. For comparison, I put a Kenwood MD on top, but it was made big rather for beauty: inside it is empty enough. But Phillips is not so.

The main board on the bottom is mainly the analog part. The digital is hidden under the metal screen, and two more boards are attached to the cassette mechanism.

Prototypes of Philips DCC tape recorders had a design that provided for vertical mounting of the cassette. Real devices almost all have a slot drive, almost like a CD. The nine-hundredth series of Philips devices in the nineties was the most top-notch: it was possible to assemble a set of CD-player, tuner, amplifier, recorder DCC, and they could all be controlled via a common bus. The price of a digital tape recorder came out rather big - $ 800 in the United States. Cassettes were sold for 8-10 dollars, slightly cheaper than minidisks at the dawn of the format. At some point, the expected savings on cheap media have disappeared somewhere. But digital cassettes could immediately record 90 minutes of music, while the first MDs were 60 minutes.

Okay, let's try to write something down. Like MDD devices, the DCC900 can record from analog and digital inputs. The devices of the first generation could process 16-bit digital sound, in later models the dynamic range was expanded to 18 bits - however, the mini-disc also learned how to do it in 1996. A tape recorder writes a so-called lead-in on an empty tape - essentially a marker indicating that the data starts here. From this point, with further recording on the very ninth data track, the absolute timer begins to be recorded. If the tape already had a recording, the tape recorder searches for an existing marker and, before starting a new recording, reproduces a piece of the old one - what if there is something valuable there? Then everything is simple: we write the sound if we need to stop. The tape recorder always reels the tape so that the next track starts exactly where the previous one ended. If necessary, press the button on the remote control or on the device itself to designate a new track.

Difficulties begin at the end of the tape. Here the developers have provided two options. Where you find that for the first side of the content is enough, you can put one of two markers. In one case, upon seeing the desired marker, the tape recorder stops playback (or recording), winds up the tape to the end, and starts a new track on side B. In the other, the tape recorder instantly switches to the second side. This option leads to the loss of several meters of tape both on the one hand and on the other, but switching between tracks on different sides is as fast as possible (but there is still a delay). Compare this to the minidisc - there is basically no such problem.

I have long wanted to buy the same album on different media. Albums on DCC are rare now: the cassette on the left cost me 10 times more than the cassette on the right, or CD .

The first generation of tape recorders did not know how to write on the tape the names of the tracks, the name of the artist and the name of the album. Generally, if you insert a handwritten cassette into the DCC900, it only shows the absolute time during playback. The track number will be displayed when you reach the nearest marker. Therefore, cassettes with music from the store are the only way to evaluate the format in all its beauty: here is the text information (there was even a record of the text of the songs in the plans), and, most importantly, the data on all the tracks were continuously recorded on the data track. At any time, you can choose any track on the album, and the tape recorder will rewind the tape itself and, if necessary, switch between the parties. Again, the advantage of the minidisc is obvious: it has a table of contents where you can record all the information and, if necessary, edit it without changing the actual recording.

All this cassette slowness was normal in the analog era, but compared to the CD, the DCC standard was seriously losing. Want to switch to a new track? Wait. Want to erase an existing marker? First find it, then erase it. If 10 tracks were recorded on a cassette, and then a part was overwritten again, it was necessary to activate a separate feature that scrolled the entire tape in search of markers and changed the track numbers, if necessary.

Part of the shortcomings of the tape recorders of the first generation were corrected in devices released later. In the second generation, the cassette mechanism was completely reworked: the carrier was now inserted sideways. They released portable players: they weighed half a kilo, worked from a proprietary battery and did not know how to record. In the third generation devices, the jambs were fixed. The last stationary Philips DCC951 tape recorder could rewind the tape from beginning to end in a minute, supported 18-bit sound, allowed to enter the names of tracks and an album.

The Philips Philips DCC170 and 175 portable players were relatively compact, supporting recording, including from digital sources. The most interesting portable model Philips DCC175. Using an optional cable, it could be connected via a parallel port to a computer. The software supported Windows 3.1 and Windows 95. It was possible to write data to the cassette (250 megabytes per 90-minute medium), and music, moreover with track names and navigation. Unlike Sony, Philips didn’t worry about protecting the data compression format — it was already half open. Modern releases on DCC cassettes (a couple of albums released last year) are written on a modified version of the DCC175.

Unfortunately, this is the most difficult to collect artifact. Portable players, developed and manufactured not by Philips, but by the Japanese partner Matsushita, were sold a little. And the DCC175 was sold only in the Netherlands, and an optional interface cable to it was generally released in 1000 pieces.

In 2019, I purchased a digital tape recorder, planning to experiment with the format, and to listen to regular audio cassettes. Why? Convenient device with remote control and auto reverse, the most it is for playback, and you can record on another technique. Alas, I didn’t succeed in exploring this use case properly - it’s all about leaky capacitors. On those two boards mounted on the DCC900 mechanism itself, SMD capacitors were used for compactness, which absolutely in all tape recorders of this series flow out over time. I bought the tape recorder as “served”, but alas, the previous owner replaced the capacitors only on the board responsible for the digital signal. The analog path simply does not work normally - the sound of one channel is missing, in the second it is very distorted. We'll have to solder. In general, the minidisk survived the test of time better than the DCC. The reason is the bet on the cassette: in each device it is necessary to replace the drive belts, and in my case also change the capacitors. Finding a minidisc deck in working condition is much easier, and minidisks themselves are generally unkillable. In the early DCC cassettes, the unfortunate material of the pads used to press the tape to the head was used; they not only squeak terribly, but also are not readable properly - the tape moves with jerks.

Why did the format fail? Previously, the main reason was considered competition with Sony. A typical format war has taken place in the home digital audio market, a battle similar to VHS vs. Betamax or Blu-Ray vs. HD DVD. This stage is actually passed almost all data carriers, including even the compact tape, but excluding the CD. One of the two formats was doomed to failure, but now we know that absolutely all physical data carriers were doomed. Both minidisk and DCC lost to cheap CD-R discs and file-sharing networks. Philips did the right thing by fixing the losses, while Sony decided to continue investing in a hopeless format, which, admittedly, was nevertheless more convenient than a digital tape.

In the history of the DCC I am interested in two points. First, was it possible to avoid such a failure and not to invest in the development of a digital cassette at all? Hardly: such complex projects last for many years, and they began in the mid-to-late eighties, when the penny was far away, computers were thin, and the web did not exist at all. At the same time, there is an increase in sales of compact discs, and generally everything is digital, and analog is considered obsolete. It is curious that since then the situation has turned 180 degrees. If you behave cautiously, you can finally give in to the competition and go bankrupt. You want - you do not want, and it is necessary to risk.

Secondly, my familiarity with the DCC shows that legacy support sometimes brings more problems than solutions. I’m already fantasizing here, but in theory, what prevented writing data on a tape in only one direction? Thus, simplifying the mechanism: the auto reverse is not needed, there is no need to invent complicated ways of switching from one side to the other, there is no inevitable pause between tracks. But then backward compatibility would be lost, which marketers relied on. I myself prefer formats or services that maintain compatibility with legacy devices for as long as possible. But the example of a minidisk shows that sometimes it is worth abandoning a heavy legacy and making it really more comfortable and compact.

Finally, the DCC shows that the product may be unsuccessful and leave the stage early, but the technologies underlying it will remain alive. The technology of creating magnetoresistive heads for a digital cassette was borrowed from hard drives, and most likely new developments have found application in the future. Wikipedia mentions an anecdotal example of the use of technology to create heads for DCC tape recorders in beer filters. Both DCC and Minidisk contributed to the development of audio compression with losses at an early stage, and now we indirectly use these developments in listening to music and in wireless transmission to headphones and through the network.

In my case, DCC was the first format that I acquired purely for studying: there could be no nostalgic background here. I decided on this experiment only because of compatibility with a traditional audio cassette. If I manage to change the capacitors, and if the board was not killed by the leaked acid, I will have a backup tape recorder. Fans of digital cassettes (they also exist) do not strongly recommend using these devices in this way - the old cassettes dirty their heads and pressure rollers much faster. But I probably will not listen to their advice. In the end, we only live once.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/447774/

All Articles