Overcoming the third law of organizational gravity

Flexibility is one of the most obvious and understandable reasons why companies put Agile in the first place among the challenges. However, many companies are still experiencing serious difficulties with a radical change in the course of development, even though the employees of these companies, including top managers, agree with the critical role of adaptability in achieving success.

Flexibility is one of the most obvious and understandable reasons why companies put Agile in the first place among the challenges. However, many companies are still experiencing serious difficulties with a radical change in the course of development, even though the employees of these companies, including top managers, agree with the critical role of adaptability in achieving success.Matt LeMay calls the main cause of such problems the third law of organizational gravity: the project will remain in motion as long as the senior executive responsible for this project is responsible. In other words, if a specific project, initiative or product idea is signed by a senior executive, then the project will continue at the same pace, even if at some point it becomes obvious that it does not meet the needs of the clients and the company's goals. In the end, why bring bad news to directors if the responsibility for the inevitable failure of the project will be placed on the shoulders of the manager?

Let us return to the first law of organizational gravity: top executives who must intervene in the process often move away from direct interaction with customers to the maximum. This creates a closed system in which companies are not able to tune the course of development for new information received from customers. Reviews that hint at a change in the course of development, combed and disguised to such a state that they sounded like "Great job, boss!". And the head gets them in this form.

This dynamic explains why people in companies often continue to work on a project, even if they are aware of its impending doom. This also explains why, in the era of instant feedback, frankly awful marketing campaigns and #socialmediafails prevail. From the point of view of internal organizational policy, public shame looks less risky than the need to inform the boss that the project he has signed is a bad idea.

')

Personal courage is one of the aspects that can work against the third law of organizational gravity, but this is not enough. The only way to make sure changes happen is to make these changes part of the process. In other words, managers who sign their projects must understand that they need to leave room for change, which is an integral part of any projects. In such a case, a change of course looks more like a meritorious example of foresight than an annoying failure.

Catherine Kuhn, an experienced Agile practitioner and lawyer who worked for Teradata, Oracle and Hewlett-Packard, explained to me how large financial companies learned to plan for uncertainty by adding shorter quarterly cycle cadences to existing annual planning cycles and integrate it into the overall company policy.

We cannot always force a company to stop creating one-year planning cycles. However, we can get them to add quarterly results reports. This is extremely simple - you begin to describe achievements for the quarter, then add additional information that others should know. Perhaps Gartner has released a new study on the topic of market changes, new regulatory requirements, new initiatives by company executives, or new information about our customers. Carry this information to the rest, describe what you learned from the last discussion of the plans, and after that look ahead. Take a look at your projects and evaluate their readiness with the knowledge you have just received. If you have achieved 85% of the goal in one project, can you strategically transfer all resources to another project that is only 20% ready?As this example shows, even companies with annual planning cycles are able to find opportunities to share knowledge and change course. Using a language that is understood within a particular company can clear the way to new ideas and methods, even if they represent significant changes for “business as usual”.

With this approach, we were able to teach the entire company to quarterly cadence event planning. This allowed them to cover all possible aspects - for example, they began to undergo audits with thousands of corrections that would have previously stopped all the work of the bank. They were able to divide the work into parts thanks to quarterly planning, understand what they can do and what they can not, and highlight the highest priorities. We began to discuss aspects that customers liked, and develop the necessary services based on them. Began to discuss the shortcomings of each approach, and not let the processes take their course.

Another key to success was that we began to speak the company's internal language - to use the phrases “not bad at the moment” and “it’s done enough”. Or "a great idea, but later." People got vocabulary for talking about assigning priorities and stopped talking too abstrusely or condescendingly.

Paradox Agile: use structure to achieve flexibility

At the core of most Agile methodologies is the paradoxical idea that regular cadence leaves more room for flexibility. This is due to the fact that a definite and final cadence, such as Agile sprints, which were discussed in Chapter 3, makes reaction to changes part of the work process, and not an obstacle to this process.

As I began to learn Agile, I was worried that a more specific structure would slow down my team and make it less responsible. The commitments to perform certain tasks every two weeks turned out to be more stringent and systemic than planning for approximate tasks for every couple of months or, even better, “for the near future”. To my surprise and delight, a shorter cadence led the team to make a clear and interesting choice. We were able to create and test prototypes of new product lines, while realizing that we can at any time abandon these areas if they prove to be useless for customers. We were also able to better plan the quarterly and annual goals of the company, because we understood that every two weeks we would be able to adjust the development course in case of deviations from the goals.

In fact, almost all companies operate within plans that go far beyond the two-week standard sprints, be it a quarterly schedule in a small technological startup or the annual budget of a large enterprise. Agile practitioners (especially those who have undergone serious ideological processing at various trainings) often refer to any long-term cadence as a threat to true flexibility and gradually begin to declare that the principles of Agile "are completely inappropriate for large and bureaucratic organizations." Alan Bunce, a consultant and former marketing manager at IBM and Salesforce.com, explained to me how the most successful Agile specialists find the golden mean between long-term planning and short-term corrections:

All the companies in which I worked, regardless of their commitment to the principles of Agile, began the fiscal year with budget planning. If you work for a company that is going to enter the open market, you can’t just say and say, “Hmm, well, we don’t know how much we have to spend, because we adhere to Agile principles!” Budget cycles are formed based on the assumptions of sales teams and their managers about realistic achievable indicators and goals for the next year. On the basis of the resulting budget is formed for marketing.This example, like the story by Catherine Kun, cited just above, shows that one-year planning does not force us to give up flexibility. Rather, on the contrary, we need to more quickly and efficiently form short cadences, with the help of which we will be able to ensure that the team’s work coincides with long-term plans and make adjustments as we receive new information from customers.

Agile principles often impose the feeling “Yes, we can rebuild at any time” - no, it is not so! You have a budget. And very quickly this budget begins to disappear. You still have plenty of room for flexible solutions, but you do not start from scratch. It is necessary to keep a balance between long-term and spontaneity.

Such a balance largely depends on how the company uses its long-term cycles. They can be carved in stone, and can have many directions of development, taking into account possible adjustments. If these long-term directions are not the ultimate truth, but rather provide guiding recommendations, then this leaves room for flexibility. But as soon as inflexibility and bureaucracy appear, “you said $ 10.1 million, not $ 9.9,” then everything becomes more complicated.

Here are a few steps you can take to combine short-term cadence, long-term goals, and planning structures.

List the established cadences of your companies and work with them, not against them.

Does your company have a one-year budget planning cycle? Biennial strategic planning cycle? Quarterly goal setting process? Take a piece of paper, write down all the cycles and indicate what exactly was decided for each cycle, who made these decisions and what result they expect. Then think about how you could build short cadences around these cycles to provide flexibility and at the same time adhere to company planning cycles that are not subject to change.

Celebrate change

If we plan only long-term cycles, any changes can seem like a tedious work on the mistakes. Short-term cycles give us more time to adjust to changes in the original plan and align new information with long-term goals. We can draw attention to the newly-minted flexibility, noting change, not mourning them. In other words, if after two short cycles within one long cycle, we understand that we are not going there, instead of the words “Damn, four weeks of work for the cat”, we can say: “We are very lucky that we noticed an error at this stage , now we can change the course of development and just as well meet the quarterly figures. ”

Focus on the possible

The tension between short-term flexibility and long-term planning will never completely disappear, so from time to time you will be in a situation where your team is not able to complete the desired task on time. However, you shouldn’t blame the whole company for “non-compliance” with Agile principles, as this will negatively affect the team’s motivation and attitude. Instead, focus on what you can accomplish, given the real limitations of the company.

In many cases, the “do what you can do” approach can add value to long-term planning cycles by clarifying their goals and expectations. While teams and companies are working to find the right balance between short-term and long-term planning, they better understand and feel the values that they themselves can offer.

Experimental work - double-edged sword

Planning uncertainty necessarily means that we make the best assumptions and move forward before we learn that our actions will bring success. In many Agile approaches and methods close to Agile, especially in the world of a lean startup, “experimental work” is often referred to as the best way to endorse new ideas and directions for teams and organizations in a rapidly changing world.

Unfortunately, existing companies are not able to ensure the sterility of a well-equipped laboratory. The idea of conducting experimental work is of great importance for the company, but it can be dangerous if it contains a feeling of scientific certainty that completely contradicts the restless and changeable nature of the real world. At best, experimental work will help to understand all the uncertainty of the world, but it will never save us from this uncertainty.

This can be a bitter lesson for teams and professionals who are pursuing extremely good decisions. There is no doubt that there are certain types of solutions that are easier to prove by experiment. For example, if you need to decide whether the “Home” button on the website’s page is round or square, then A / B testing will be the most effective solution. And now suppose that you need to decide whether to develop a new business line, or what awaits an existing product in a new market. Of course, you can conduct an experiment that will help find answers to these questions and will cost you all the costs, but no such experiment will provide you with the same irrefutable scientific certainty as simple A / B testing.

Theoretically, this means that teams should stop wasting time on complex and intricate experiments that confirm complex market-oriented solutions. However, in practice, this often means something completely different: teams and organizations spend a disproportionately large amount of time on experiments that provide confirmation in absolute quantitative form, even if these experiments do not have a particular impact on the business.

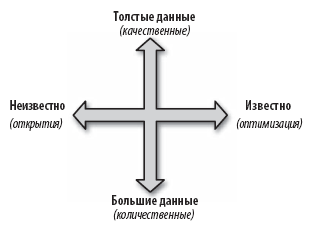

When my business partners and I worked with companies, we often asked them to display the experiments they were conducting on a graph called Integrated Data Analysis. Such four-quadrant graphs display data-related initiatives along the discovery-optimization and qualitative-quantitative axes. Trisha Von, a Sudden Compass partner, developed this framework after she had to deal with many companies that relied too much on quantitative optimization work, such as A / B testing, and neglected the more complex and endorsement work at opening and conducting experiments that by their nature provide qualitative data.

When my business partners and I worked with companies, we often asked them to display the experiments they were conducting on a graph called Integrated Data Analysis. Such four-quadrant graphs display data-related initiatives along the discovery-optimization and qualitative-quantitative axes. Trisha Von, a Sudden Compass partner, developed this framework after she had to deal with many companies that relied too much on quantitative optimization work, such as A / B testing, and neglected the more complex and endorsement work at opening and conducting experiments that by their nature provide qualitative data.Virtually every company with which we performed this exercise filled out a chart with a pronounced bias towards quantitative optimization in the lower right quadrant. However, when we asked the same organizations to display questions that worry them a lot, along the x axis from “discovery” to “optimization”, the bias went to “discovery”. Companies are often asked general questions about discoveries: “How can we introduce our business to new markets?”, While continuing to carry out most of the experiments with regard to additional optimization of existing products, markets, or promises. The mere recognition of this fact is often not enough for companies to pay attention to this problem and begin to explore new ways of conducting qualitative experiments at the level of discoveries in the upper left quadrant.

One of the best examples of such an experiment is taken from the book “Thrifty Startup” . Sarah Milstein, the former president and co-founder of Lean Startup Productions, explained to me how she could conduct simple, low-cost experiments to evaluate new product ideas and why qualitative data played an important role in these experiments:

When we launched a new conference as part of Lean Startup Productions, we thought about selling online tickets. We did not think it would be so popular, so we expected to sell about ten tickets. On the day of the sale, we sold a hundred tickets. It was a serious signal, since we could not analyze the behavior of our clients. If we had not thought about this idea, we would not have seen the difference between ten and a hundred tickets. Such an experiment, based on a hypothesis, is no less useful if you make a mistake; in addition, you do not need to strive to be right, you need to strive to assess your own judgments about the client you serve.As this story shows, the simplest things to measure are not always the most important and relevant. When we start with the most important questions concerning business and customers, and not with questions that are easiest to answer with a quantitative experiment, we recognize the complexity and uncertainty of the world around us.

It is also worth noting that people are often very addicted to experiments, because of what their meaning begins to get lost. Sometimes an experiment delivers exceptionally high quality signals: for example, when people start using a phrase from your marketing materials. This approach is officially called “artifact analysis”. For example, if we call feedback on our site “questions,” will the content of the inbox change? We do not always have numbers, but we know what and where to look.

An excerpt from the book "Agile for All"

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/446608/

All Articles