Clouds and powder keg Open Source

“Europe today looks like a powder magazine, and leaders look like people smoking inside. One spark will cause an explosion that will bury us all. I do not know when this will happen, but I know where. Any foolish event in the Balkans will ruin everything ”- Otto von Bismarck, 1878

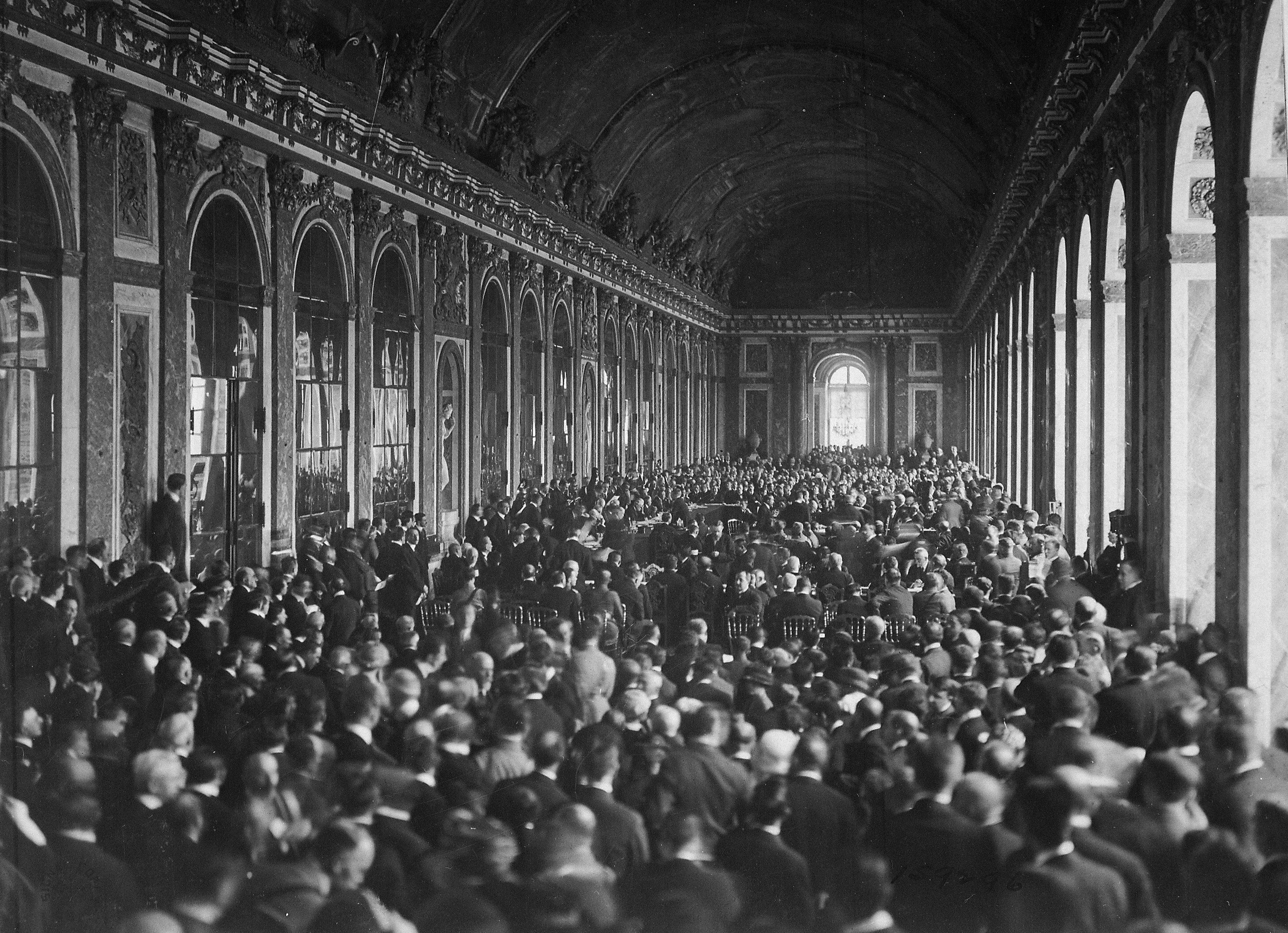

One hundred years ago, on November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed, ending the First World War. The number of lost lives in that war is now difficult to imagine. For example, in America, the Vietnamese war is rightly considered a military catastrophe. Over twenty years of fighting the United States lost 58,318 fighters. For comparison, only in the first battle of the Marne in 1914, the Allies lost four times more. For five days.

Some would say that the horrors of war could not be predicted. The problem is that at least some of the parties involved were well aware of the consequences. British Foreign Secretary Edward Gray, after speaking in parliament in support of the war, is said to have said: “The lights go out throughout Europe. With our lives, they will no longer catch fire. ”

')

Therefore, in subsequent years, historians tried to answer the question: if the consequences were clear, then how was the July crisis admitted - a series of related events, as a result of which war was the only possible outcome.

Although extremely complex in details, the answer is simple. Given the atmosphere and political structures of the time, none of the participants in the events felt that he had an alternative. One of the most frightening things in studying the causes of war, in fact, is that if you are considering the political realities of the time, it is actually easy to understand the justifications for the actions of each state.

In the end, we agree that war was inevitable. The ease of accepting this truth is really scary.

Three years ago, a venture capital fund brought together a small group of media representatives, vendors and analysts, including us, to discuss the importance of open source in commercial activities. After the presentation of his own model, the partner of the venture company presented a group of managers from partner commercial open source companies. Each of them described in detail how open source replaced proprietary alternatives to customers.

Of course, we agree that the shift of developers to open source across the enterprise is changing the nature of supply. To some extent, this is the main conviction that we have been promoting for many years. Back in 2011, we published an article “Implementation of the bottom-up: the end of the supply, as we know it . ” But in the proposed model it was interesting not what it tells about the present, but rather what it cannot say about the future.

The event did not directly mention cloud services. It was said that investors and commercial developers of OSS compete with proprietary software. No special attention was paid to Amazon and other suppliers of large-scale clouds, they were not even named. The question on this subject was politely rejected.

This is interesting because at that time we at RedMonk in evaluating commercial open source teams offered them to answer the standard simple question: “Who is your competitor?” If they called a proprietary alternative, this suggested that the company was a thing of the past. If the answer was a cloud, it was safe to assume that the startup is looking forward.

As we see, now this thinking has reached the market. In the last 12-18 months, in fact, there was a coup. If before the company did not consider worthy of mention cloud providers such as Amazon, Google and Microsoft, now they regard them as a deadly threat. The fear of cloud providers has become so overwhelming that commercial open source providers often, contrary to the advice of consultants, make strategic decisions that violate open source cultural norms, cause massive and sustained negative public relations and threaten relationships with developers, partners and customers. In particular, they are increasingly turning to models that blur the boundaries between open source and proprietary software in an attempt to take advantage of both worlds, but in the end it is highly likely that they will get the disadvantages of both.

Commercial providers of open source have taken these actions, having been informed in advance of the risks. This speaks of their assessment of their prospects in a world where massive clouds, expanding the range of services, increasingly dominate. Undoubtedly, such strategic decisions have serious, inevitable negative consequences, but open source commercial suppliers — or, at least, their investors — consider the absence of actions to be an even more destructive option.

It is interesting to see whether this conviction will continue after the announcement of Amazon Web Services this week. Here is a summary of the story that led to current events:

- 2010 : written by Shey Banon almost a decade ago, Elasticsearch is an open source search system with a licensing license. It turned out to be popular enough to form a commercial organization around it. Elastic NV - originally Elasticsearch BV - went through several rounds of financing totaling more than one hundred million dollars, held an IPO last October, and is now estimated at just under $ 6 billion.

- 2015 : five years after the founding of the project — presumably at the request of customers — Amazon launched a cloud service called Amazon Elasticsearch Service based on this licensing license. He directly competed with Elastic NV's commercial offerings, both local and cloud.

- 2018 : Partly due to the competition with this and other clouds, Elastic NV began to blur the boundaries between its open source offering and proprietary licensed additions to it, in particular, x-pack. It is noteworthy that Elastic did not follow in the footsteps of some colleagues, but tried to solve the problem with the help of hybrid licenses, but started mixing open and proprietary source code in one repository, and the builds included this non-free software by default.

- 2019 : Amazon has taken some response this week. First, with the support of Expedia and Netflix, she presented what she sees as the “distribution” of Elasticsearch. But it is assumed that in all respects it will function as a fork. Secondly, the project includes open source add-ons, similar to the functions for which Elastic NV charges fees, without putting them into free access. Third, as was the case with the original AWS service based on Elasticsearch, the company used the name Elasticsearch for the project.

Considering that the previous contradictions have become an open conflict, many questions arise. How did it come to this? Is it really inevitable? And the obvious question is: who is to blame?

At least one of these questions is easy to answer. This step has been expected for some time. At least since September, when the Commons Clause license appeared:

Of course, it seems incredible that cloud providers everywhere will start deploying and licensing open source software from commercial vendors under a Commons Clause license. In fact, Commons Clause may be counterproductive. It increases the likelihood that cloud providers will try to lure key developers and make a public or private fork of the project. This is a cheaper option, which also provides the necessary control over software assets.

The controversy between Amazon and Elastic is the result of a collision of models. To the credit of Banon and Elastic, Elasticsearch software has proven to be extremely popular, also thanks to a licensing license.

However, licenses allow the use of the system and cloud providers such as Amazon. In order not to miss profits and satisfy the demands of their customers, cloud providers will certainly offer native services for Elasticsearch and similar projects that are popular and well known.

- Licensing is unrealistic. Despite the opinion of some investors, in fact, adding commercial terms to previously free software will never force the largest cloud service providers to sign up. No company operating on such a scale will want to provide a major service — be it product development or pricing — to a third party that they do not control.

- Acquisition is another option to meet demand, but it doesn’t scale well. Even rich cloud providers do not want to pay extra money for the purchase of each new service in their portfolio, especially when there is a cheaper and simpler alternative - and here it is.

- In open source communities, fork has historically been viewed as a toxic option, but from a PR point of view, it becomes more acceptable if a commercial open source provider jeopardizes its own status by adopting tactics and methods that are contrary to the open source community. In this case, even large third parties may try to occupy a higher moral position, while simultaneously serving their own interests.

Faced with these options, the fork seems to be the logical response of the cloud service to the appearance of adverse licensing conditions. That's why Amazon’s decision was expected and inevitable. And so it is difficult to identify the culprit in this situation. In principle, both parties acted logically - in the way that could be expected, given their prospects, opportunities and legal rights.

It is likely that Amazon will be the first, but not the last cloud provider to do so. Others will also try to reconcile consumer demand with a lack of legal restrictions on creating their own projects, such as the “open source distribution for Elasticsearch”. Probably, they will inevitably come to the conclusion that it is profitable. Apparently, from commercial providers of open source, there will also inevitably be a conclusion that the cloud is so great a threat that open source boundaries should be expanded.

In fact, the only real question is whether open source developers will draw a conclusion from the current situation with Elastic, which now competes with Amazon not only in terms of products, but also in open sources. Will they understand that the benefits of some controversial licensing approaches simply do not justify the costs.

However, it is more likely that the status quo will remain. The incentives and motives of both sides are clear, understandable and logical in the context of their respective models. Models that will always internally contradict each other, even if they are inextricably linked.

A hundred years ago, leaders of dozens of countries decided to enter into conflict. They knew that the conflict would cost them dearly, would be appallingly destructive, and hardly anyone would emerge victorious. They did this because they did not see another way out.

The technology industry does not seem to see either.

Note: Amazon and Elastic are RedMonk clients, as are Google and Microsoft. Expedia and Netflix are not RedMonk clients.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/444962/

All Articles