The first programmed computer on DNA

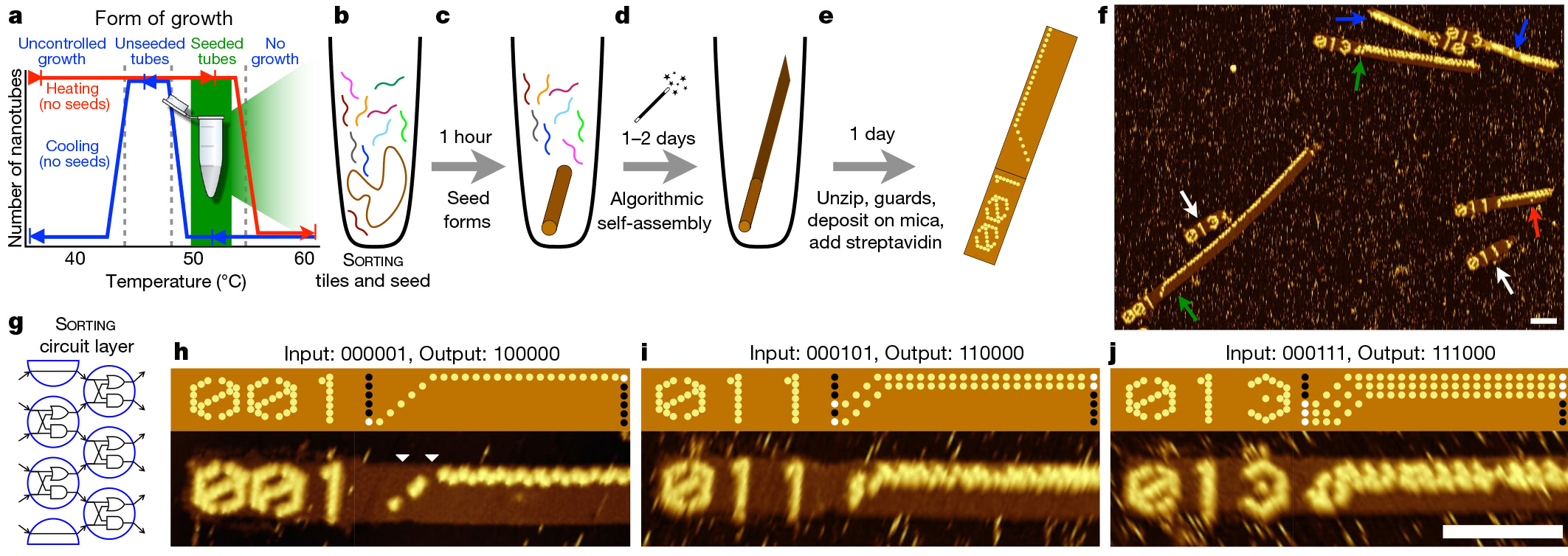

Experimental protocol and implementation of the sorting algorithm on a programmable DNA computer

Scientists have long been experimenting with storing information in DNA and processing this information. For example, scientists from the University of Washington and Microsoft recently built "the world's first DNA-hard drive" ( photo ). This design is capable of providing for the first time the recording and reading of information in DNA storage without human intervention. A very significant achievement, given that the DNA can be recorded information with a density of 2.2 petabyte per gram . DNA is a compact container with a recording density thousands of times greater than that of existing media.

However, all existing DNA systems have a problem: all of these are unique proprietary developments that lack any flexibility whatever. If we compare it with silicon technology, then each group of researchers from scratch is developing a new computer architecture for which it is necessary to write a new software. But the situation may change thanks to the first programmable DNA computer developed at the University of California, Davis, California Institute of Technology and Meinuth University.

The first programmable computer on DNA is described in a scientific paper published March 20, 2019 in the journal Nature. The authors showed that using a simple trigger, the same basic set of DNA molecules is capable of implementing many different algorithms. Although the study is a purely laboratory experiment, in the future programmable molecular algorithms can be used, for example, to program DNA robots that already successfully deliver drugs to cancer cells .

')

"This is one of the landmark works in this area," said Torsten-Lars Schmidt, an assistant professor of experimental biophysics at the University of Kent, who did not participate in the research. “We have already demonstrated algorithmic self-assembly, but not to such a degree of complexity.”

In electronic computers, bits are binary units of information. They represent the discrete physical state of the base equipment, for example, the presence or absence of electric current. These bits, or rather, electrical signals, are passed through circuits consisting of logic elements that perform an operation on one or more input bits and produce one bit as an output.

Combining these simple building blocks over and over again, computers can run surprisingly complex programs. The idea of DNA computing is to replace electrical signals with chemical bonds, and silicon - with nucleic acids to create biomolecular software.

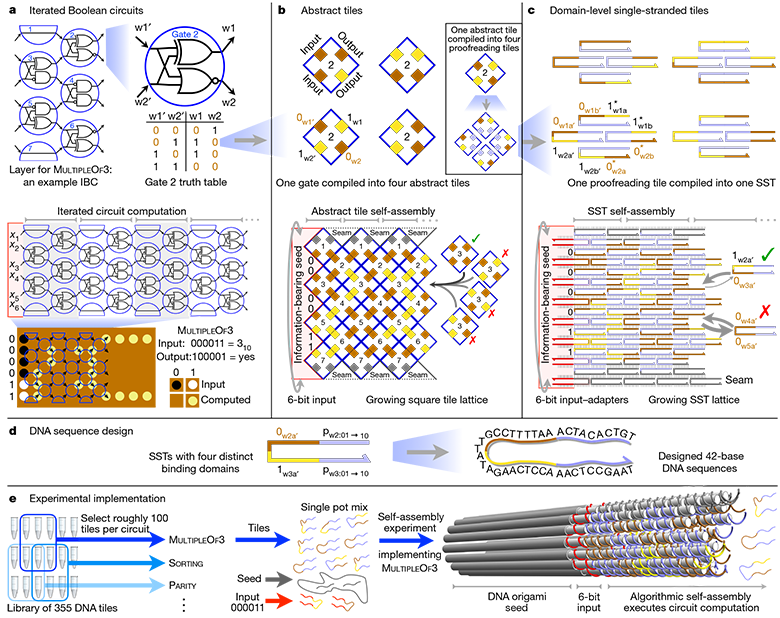

Abstract hierarchy of architecture and practical implementation of a full 6-bit IBC logic circuit (Iterated Boolean Circuit)

According to Eric Winfrey, a Caltech scientist and co-author of the article, molecular algorithms use the natural possibilities of processing information in DNA, but instead of allowing nature to take the reins in their hands, calculations in DNA are made according to a program written by man.

Over the past 20 years, several successful experiments have been carried out with molecular algorithms, for example, for playing tic-tac-toe or assembling molecules of various shapes. In each case, careful DNA sequence development was required to perform one specific algorithm that would generate the DNA structure. In this case, the difference lies in the fact that researchers have developed a system in which the same basic DNA fragments can be ordered to create completely different algorithms - and, therefore, obtain completely different results.

The process begins with a DNA origami technique, that is, folding a long strand of DNA into the desired shape. This folded piece works as a seed, which launches an algorithmic assembly line. Seed remains almost unchanged, regardless of the algorithm. For each experiment, it makes only small changes in several sequences.

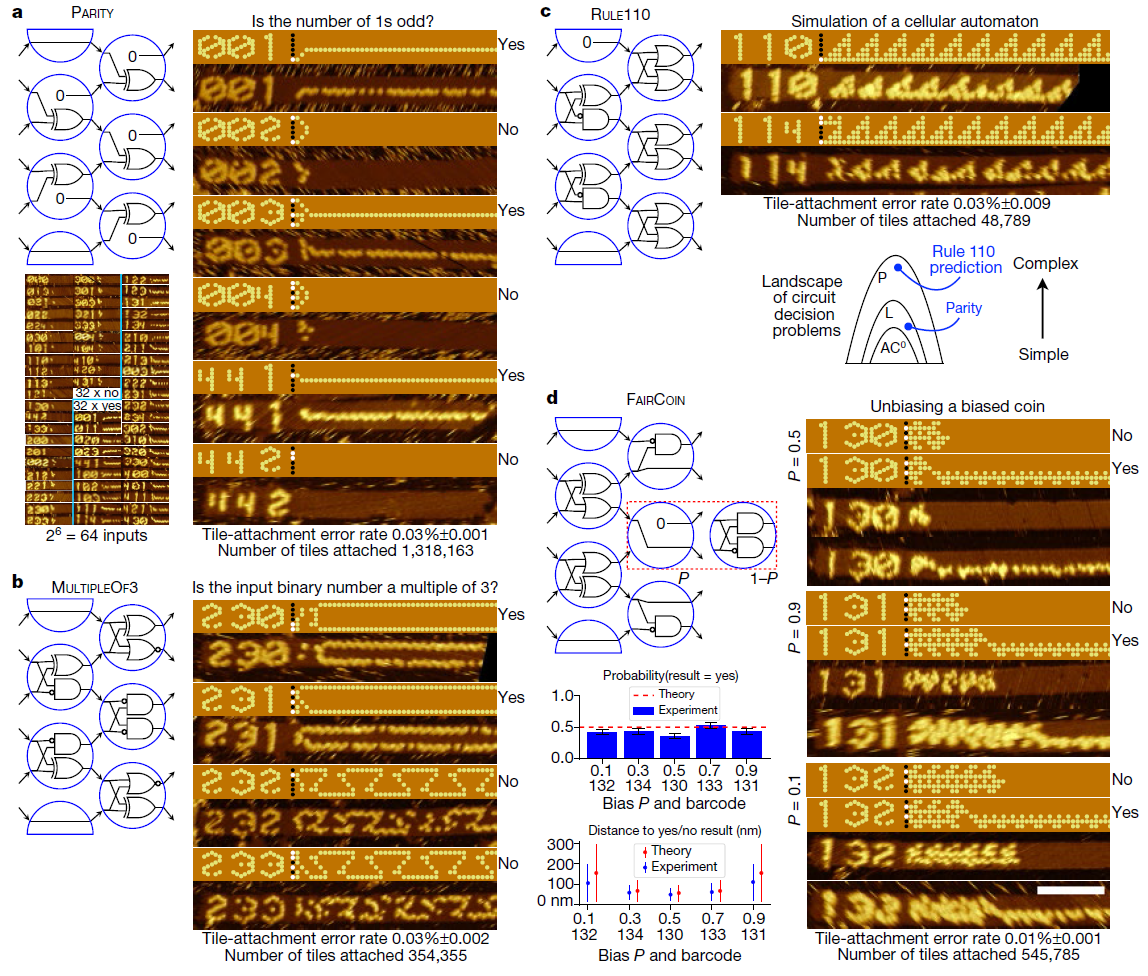

Reprogramming logic circuit

After creating the "seed" it is added to the solution with hundreds of other DNA strands, known as DNA tiles. Scientists have developed 355 of these tiles. Each has a unique location of nitrogen bases. Accordingly, for each algorithm, the researchers simply select a different set of starting tiles. Since these DNA fragments are connected during the assembly process, they form a circuit that implements the selected molecular algorithm on the input bits provided by the “seed”.

Using this system, the researchers developed and tested 21 algorithms for performing tasks such as recognizing division into three, choosing a leader , generating patterns and counting from 0 to 63. All these algorithms are implemented using different combinations of the same 355 tiles of DNA.

Of course, it’s not easy to write code, dropping DNA fragments into a tube, but if you automate the process, then future molecular programmers don’t even have to think about biomechanics, as today's programmers need not understand the physics of transistors to write good programs.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/444842/

All Articles