DeepMind and Google: the battle for control of a strong AI

Demis Hassabis founded the company to create the most powerful AI in the world. Then bought it google

In August 2010, a 34-year-old Londoner named Demis Hassabis appeared on the stage in a conference room in the suburb of San Francisco. He emerged with a leisurely gait of a man who is trying to control his nerves, squeezed his lips in a brief smile and began: “So today we will talk about different approaches to the development ...” - he faltered, as if suddenly realizing that he was voicing hidden ambitious thoughts. But then he still said: "... a strong AI."

Strong AI (artificial general intelligence or AGI) means universal artificial intelligence - a hypothetical computer program that can perform intellectual tasks as a person or even better. A strong AI will be able to perform individual tasks, such as photo recognition or text translation, which are the only tasks of each of the weak AI in our phones and computers. But he will also play chess and speak French. Will understand articles on physics, write novels, develop investment strategies and lead delightful conversations with strangers. It will monitor nuclear reactions, manage electrical grids and traffic flows and without much effort succeed in everything else. AGI will make today's most advanced AI look like a pocket calculator.

The only intelligence that is currently capable of performing all these tasks is the one that people are endowed with. But human intelligence is limited by the size of the skull. The power of our brain is limited by the minute amount of energy that the body is able to provide. Since AGI works on computers, it will not suffer from any of these limitations. Strong intelligence is limited only by the number of available processors. He can start by monitoring nuclear reactions. But rather quickly, it will open up new sources of energy, digesting in a second more scientific works in physics than a man can do in a thousand lives. Human intelligence, combined with the speed and scalability of computers, will make problems that currently seem intractable disappear. In an interview with the British Observer, Hassabis said that, among other things, strong AI must master such disciplines and solve problems such as "cancer, climate change, energy, genomics, macroeconomics [and] financial systems."

')

The conference at which Hassabis spoke was called Singularity Summit. According to futurologists, singularity refers to the most likely consequence of the appearance of AGI. Since it processes information at high speed, it will very quickly grow wiser. Fast self-improvement cycles will lead to an explosion of machine intelligence, leaving people far behind to suffocate from silicon dust. Since this future is built entirely on the foundation of unverified assumptions, the question of whether to consider singularity as a utopia or hell is almost religious.

Judging by the titles of the lectures at the conference, the participants are motivated to messianism: “Reason and how to build it”; “AI as a solution to the problem of aging”; "Replacing our bodies"; "Changing the boundary between life and death." The Hassabis lecture, on the other hand, does not look very impressive: "A systemic neurobiological approach to building AGI."

Hassabis walks between the podium and the screen, quickly saying something. He's wearing a maroon jumper and a white button-down shirt, like a schoolboy's. A small increase only seems to enhance his intellect. Until now, explained Hassabis, scientists approached AGI from two sides. In the field of symbolic AI, researchers tried to describe and program all the rules for a system that could think like a person. This approach was popular in the 80-90s, but did not give the desired results. Hassabis believes that the mental structure of the brain is too refined to describe it in this way.

In another area, researchers worked who tried to reproduce the physical networks of the brain in digital form. This was a definite meaning. After all, the brain is the seat of the human intellect. But these researchers were misled, Hassabis said. Their task was about the same scale as an attempt to map all the stars in the universe. Moreover, it focuses on the wrong level. This is like trying to understand how Microsoft Excel works by disassembling a computer and studying the interactions of transistors.

Instead, Hassabis proposed a middle ground: a strong AI must draw inspiration from the broad methods by which the brain processes information, not from physical systems or specific rules that it applies in specific situations. In other words, scientists should focus on understanding the software of the brain, not its hardware. New methods, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging, allow you to look inside the brain during its activity. They make such an understanding possible. Recent studies have shown that the brain learns in a dream, reproducing the experiences that have been received, in order to deduce general principles. AI researchers should emulate this system.

A logo appeared in the lower right corner of the slide - a round blue whirlpool. Below it are two words: DeepMind. This was the first public mention of the new company.

Hassabis spent a whole year trying to get an invitation to the Singularity Summit. The lecture was just a cover. What he really needed was one minute with Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley billionaire who financed the conference. Hassabis wanted his investment.

Hassabis never said why he wanted to get support from Till (for this article he, through the press secretary, refused several requests for an interview). We spoke with 25 sources, including current and former employees and investors. Most of them spoke anonymously, since they had no right to talk about the company. But Thiel believes in AGI with even more fervor than Hassabis. In his speech in 2009, Thiel said that his greatest fear for the future is not the uprising of robots (although in isolated New Zealand, he is better protected than most people). Rather, he fears that the singularity will come too late. The world needs new technologies to prevent a recession.

In the end, DeepMind received £ 2m in venture financing; including £ 1.4m from til. When Google bought the company for $ 600 million in January 2014, early investors recorded a profit of 5,000%.

For many founders, this would be a happy ending. You can slow down, take a step back and enjoy the money. For Hassabis, the Google deal was another step in his quest for a strong AI. Almost all of 2013 he spent in the negotiations on the transaction. DeepMind will operate separately from the parent company. Hassabis will receive all corporate privileges, such as access to cash flow and computing power, without losing control of the company.

Hassabis thought DeepMind would become a hybrid: he would have a startup drive, the brains of the greatest universities, and the deep pockets of one of the richest companies in the world. Everything was done in order to speed up the development of a strong AI and help humanity.

Demis Hassabis was born in North London in 1976 to a Greek Cypriot and Chinese Singaporean family. He was the eldest of three brothers and sisters. Mom worked at the John Lewis department store, and her father worked at the toy store. The boy learned to play chess at the age of four, watching his father and uncle play. After a few weeks, adults could no longer win him. For 13 years, Demis became the second chess player of the world at his age. At the age of eight, he independently learned how to program.

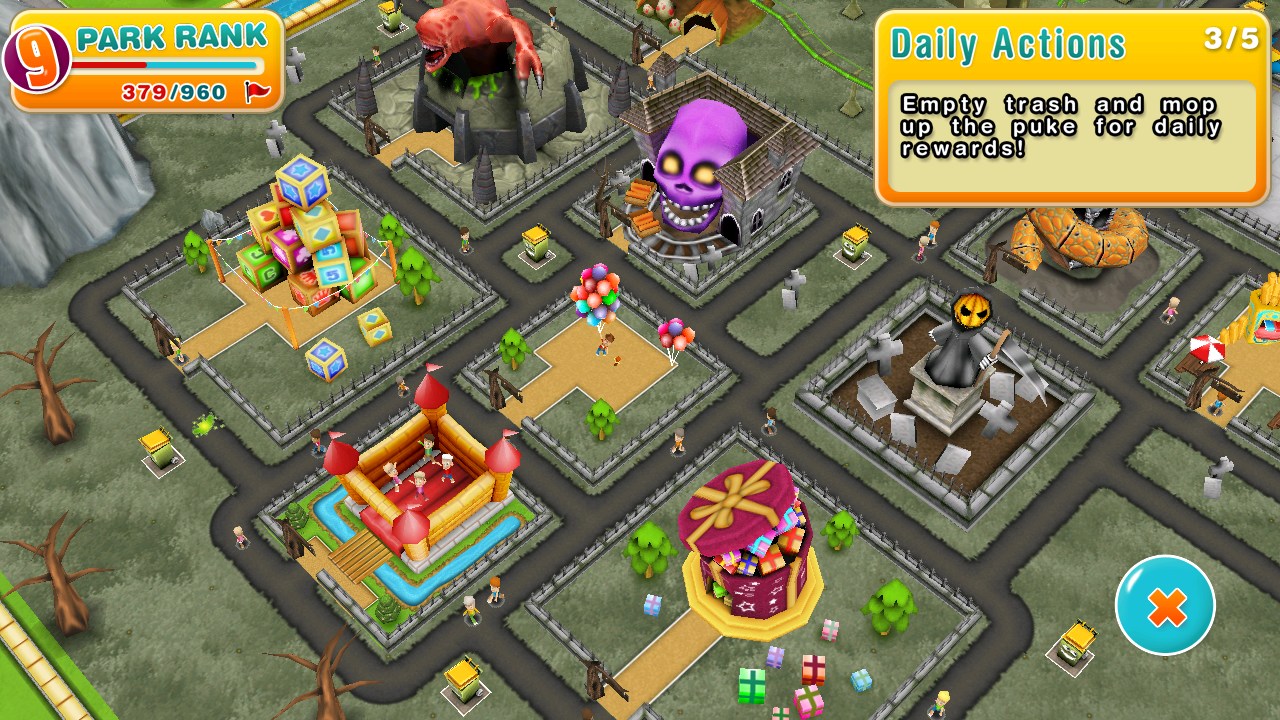

In 1992, Hassabis graduated from school two years ahead of schedule. He got involved in programming video games at Bullfrog Productions, where he wrote Theme Park. In it, the players built and managed a virtual amusement park. The game was very successful with 15 million copies sold. It belonged to a new genre of simulators, in which the goal is not to defeat the enemy, but to optimize the functioning of such a complex system as a business or a city.

Theme Park for Android, 2018

Demis not only developed the games, but also played great in them. As a teenager, he was torn between competitions in chess, scrabble, poker and backgammon. In 1995, studying computer science at the University of Cambridge, Hassabis got to the student tournament in go. This is an ancient board strategy game, which is much more difficult than chess. It is assumed that the skill requires intuition, acquired by long experience. No one knew if Hassabis had played before.

First, Hassabis won the tournament for beginners. Then he beat the winner of the tournament for experienced players, albeit with a handicap. The organizer of the tournament, Cambridge master of go, Charles Mathews, remembers the shock of an experienced player after losing to a 19-year-old novice. Matthews took Hassabis under his care.

Hassabis' intelligence and ambitions have always been manifested in games. The games, in turn, aroused interest in the intellect. Watching his progress in chess, he wondered if computers could be programmed to learn like him, based on experience. The games offered a learning environment that the real world could not match. They were clear and self-sufficient. Since the games are separated from reality, they can be practiced without interfering with the real world and effectively mastering them. Games speed up time: in a couple of days, you can create a criminal syndicate, and the Battle of the Somme ends in a matter of minutes.

In the summer of 1997, Hassabis went to Japan. In May of the same year, IBM's Deep Blue computer defeated world chess champion Garry Kasparov. For the first time, the computer won a chess grandmaster. The match attracted worldwide attention and raised concerns about the growing power and potential threat of computers. When Hassabis met the Japanese master of board games, Masahiko Fujzueraa, he told him about a plan that unites his interests in strategic games and artificial intelligence: one day he will build a computer program that will win the greatest go player.

Hassabis acted methodically: “At the age of 20, Hassabis was of the opinion that certain things must be in place before he does the AI at the level he wanted,” says Matthews. “He had a plan.”

In 1998, he founded his own gaming studio Elixir. Hassabis focused on one extremely ambitious game: Republic: The Revolution, a sophisticated political simulator. Many years ago, at school, Hassabis told his friend Mustafa Suleiman that the world needed a grandiose simulator to simulate its complex dynamics and solve the most complex social problems. Now he tried to do it in the game.

It was harder to fit into the game frame than he expected. In the end, Elixir released an abbreviated version of the game to soften feedback. Other games failed (including the villain simulator of the bondian called Evil Genius). In April 2005, Hassabis closed down Elixir. Matthews believes that Hassabis founded the company simply to gain management experience. Now Demis lacked only one important area of knowledge to start working on a strong AI. He needed to understand the human brain.

In 2005, Hassabis received a doctorate degree in neuroscience from the University College of London (UCL). He published the famous studies of memory and imagination. One of his articles, which has since been quoted more than 1,000 times, showed that people with amnesia also have difficulty comprehending new experiences, suggesting that there is a link between memorization and the creation of mental images. Hassabis created a brain representation suitable for the task of creating an AGI. Most of the work came down to one question: how does the human brain receive and preserve concepts and knowledge?

Hassabis officially founded DeepMind on November 15, 2010. The company's mission has not changed since: “solve the intellect,” and then use it to solve the rest. As Hassabis told the Singularity Summit participants, it means translating our understanding of the principles of how the brain works into software that can use the same methods of self-study.

Hassabis understands that science has not yet fully comprehended the essence of the human mind. A project of strong AI cannot simply be created on the basis of hundreds of neurobiological studies. But he clearly believes that we already know enough to start working on a strong AI. Yet there is a chance that his confidence is ahead of reality. We still know very little about how the brain actually functions. In 2018, the results of Hassabis' own doctoral thesis were questioned by a team of Australian researchers. This is just one article, but it shows that the scientific opinions underlying DeepMind are far from consensus.

The co-founders of the company were Mustafa Suleiman and Shane Legg, an AGI-obsessed New Zealander, whom Hassabis also met at UCL. The company's reputation grew, and Hassabis was reaping the fruits of his talent. “He’s like a magnet,” says Ben Faulkner, a former DeepMind operations manager. Many employees lived in Europe, far from the HR departments of Silicon Valley giants such as Google and Facebook. Perhaps the main achievement of DeepMind was hiring employees immediately after the foundation in order to find and retain the brightest and best talents in the field of AI. The company opened an office in the attic of a townhouse on Russell Square in Bloomsbury, across the street from UCL.

One of the machine learning methods that the company focused on grew out of Hassabis’s double hobby for games and neuroscience: this is reinforcement learning. Such a program is designed to collect information about the environment, and then study it, repeatedly reproducing the experience, like the activity of the human brain in a dream, as Hassabis told in his lecture at the Singularity Summit.

Reinforcement training starts from scratch. The program is shown a virtual environment, about which it knows nothing but rules. For example, a simulation of a game of chess or video games. The program contains at least one component known as a neural network. It consists of layers of computational structures that sift through information to identify specific functions or strategies. Each layer explores the environment at a new level of abstraction. At first, these networks act with minimal success, but it is important that each failure leaves a mark and is encoded within the network. Gradually, the neural network becomes more sophisticated, as it experiments with different strategies - and receives an award if it is successful. If the program moves a chess piece and as a result loses the game, it will not repeat this error anymore. Most of the magic of artificial intelligence lies in the speed with which he repeats his tasks.

The culmination of DeepMind's work was 2016, when the company released AlphaGo, which used reinforcement training along with other methods to play go. To everyone's surprise, in the five-match duel in Seoul, the program beat the world champion. 280 million spectators watched the victory of the car: this event happened a decade earlier than experts had predicted. The following year, an improved version of AlphaGo defeated the Chinese champion of go.

Like Deep Blue in 1997, AlphaGo changed the perception of what human excellence consists of. Board game champions, some of the most brilliant minds on the planet, were no longer considered the pinnacle of intelligence. Almost 20 years after talking with the Japanese master Fujvarea Hassabis kept his promise. Later he said that he almost cried during the match. According to tradition, the student makes thanks to the teacher, defeating him in the match. Hassabis thanked Matthews, defeating the game entirely.

DeepBlue won because of the brute force and speed of computation, but the AlphaGo style seemed artistic, almost human. His grace and sophistication, the superiority of the computational musculature seemed to show that DeepMind, further than its competitors, advanced in developing a program capable of curing diseases and managing cities.

Hassabis has always said that DeepMind will change the world for the better. But in a strong AI there is no certainty. If he ever arises, we do not know whether he will be altruistic or malicious, whether he will submit to human control. Even so, who will take control?

From the very beginning, Hassabis tried to protect the independence of DeepMind. He always insisted that DeepMind stay in London. When Google bought the company in 2014, the issue of control became more relevant. Hassabis was not obliged to sell the company. He had enough money, and he sketched out a business model for which the company develops games to fund research. Google’s finances weighed, but, like many founders, Hassabis didn’t want to give up the company he had grown. As part of the deal, DeepMind has entered into an agreement that will not allow Google to unilaterally take control of the company's intellectual property. According to an informed person, before the transaction, the parties signed a contract called the Ethics and Safety Review Agreement. The previously unreported agreement was drafted by serious London lawyers.

The agreement transfers control over the core technology of a strong AI to DeepMind whenever this AI is created, namely to a steering group called the Ethics Board. According to the same source, the Ethics Council is not some kind of cosmetic concession from Google. It gives DeepMind strong legal support to maintain control over its most valuable and potentially most dangerous technology. The names of the council members were not made public, but another source close to DeepMind and Google says it includes all three of the founders of DeepMind (the company declined to answer questions about the agreement, but said that “ethics control from the first day was for us priority ").

Hassabis can determine the fate of DeepMind and otherwise. One of them is the loyalty of the staff. Past and current employees say that the Hassabis research program is one of DeepMind's greatest strengths. His program offers an exciting and important job, free from the pressure of academic circles. Such conditions have attracted hundreds of the most talented experts in the world. DeepMind has subsidiaries in Paris and Alberta. Many employees feel more intimate with Hassabis and his mission than with the income-hungry parent corporation. As long as Hassabis retains personal loyalty, he has considerable power over his sole shareholder. For Google, it's better for DeepMind's talents to work for it through an intermediary than they go to Facebook or Apple.

DeepMind has another lever, although it requires constant replenishment: favorable advertising. The company succeeds in this. AlphaGo has become a real PR bomb. Since the acquisition of Google, the company has repeatedly produced wonders that have attracted the attention of the whole world. One DeepMind program is able to diagnose eye diseases by retinal scan. Another learned how to play chess from scratch using AlphaGo-style architecture, becoming the greatest chess player of all time in just nine hours of self-study. In December 2018, a program called AlphaFold outperformed competitors in the task of predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins in the list of components, potentially paving the way for the treatment of diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease.

DeepMind is especially proud of the developed algorithms that compute the most efficient means of cooling Google data centers, which employs approximately 2.5 million servers. DeepMind said in 2016 that they reduced Google’s electricity costs by 40%. But some insiders say that this is an exaggerated figure. Google used algorithms to optimize data centers long before DeepMind: “They just want to have some PR to increase their value in Alphabet,” says one Google employee. Google's maternal company Alphabet pays DeepMind generously for such services. So, in 2017, DeepMind billed her for £ 54 million. This figure pales in comparison with the current expenses of DeepMind: only 200 million people were spent that year on personnel. In general, DeepMind's losses in 2017 were £ 282 million.

This is a pittance for a rich Internet giant. But other loss-making Alphabet companies caught the attention of Ruth Porat, the frugal chief financial officer of Alphabet. For example, the Google Fiber division tried to create a high-speed Internet provider by passing fiber-optic lines to private homes. But the project was suspended when it became clear that it would take decades to recover the investment. Therefore, it is important for AI researchers to prove their relevance in order not to attract the tenacious gaze of Mrs. Porat, whose name has already become a common noun in Alphabet.

DeepMind's systematic achievements in the field of AI are part of a relationship strategy with company owners. DeepMind signals its reputational power. This is especially important when Google is accused of invading the privacy of users and spreading fake news. DeepMind was also lucky to have a supporter at the highest level: Larry Page, one of the two founders of Google, now the executive director of Alphabet. Paige is the closest thing Hassabis has in the parent company. Page's father, Karl, studied neural networks in the 60s. At the beginning of his career, Page said that he created Google solely to establish an AI company.

Tight control over DeepMind to look good in the eyes of the press does not exactly match the academic spirit that permeates the company. Some researchers complain that it is difficult for them to publish their work: they have to overcome several levels of internal censorship before they can at least present a report for a conference or an article for a journal. DeepMind believes that it is necessary to act carefully so as not to scare the public with the prospect of a strong AI. But too dense silence can spoil the academic atmosphere and weaken the loyalty of employees.

Five years after Google’s acquisition, the question of who controls DeepMind comes to a critical point. The company's founders and first employees will soon be able to leave with their financial compensation (Hassabis shares are likely to cost about £ 100 million after buying Google). But a source close to the company suggests that Alphabet pushed the time to monetize founder options for two years. Given its relentless focus on the mission, Hassabis is unlikely to leave the ship. Money interests him only insofar as they help to achieve the goal of a lifetime. But some colleagues have already left. From the beginning of 2019, three AI engineers left the company. And Ben Laurie, one of the world's most famous security professionals, has now returned to Google, to his previous employer. This number is small, because DeepMind offers such an exciting mission and decent pay that few people leave.

Until now, Google has not intervened in the DeepMind. But one recent event raised concerns about how long the company could remain independent.

DeepMind has always planned to use AI to improve healthcare. In February 2016, a new division, DeepMind Health, was created, headed by Mustafa Suleiman, one of the co-founders. Suleiman, whose mother worked as a nurse in the National Health Service (NHS), was hoping to create a program called Streams that would alert doctors when the patient's health deteriorates. DeepMind had to earn on every effective system response. Because this work required access to confidential patient information, Suleiman established the Independent Review Panel (IRP), which included representatives from the British healthcare and technology sector. DeepMind acted very carefully. Subsequently, the British Information Commissioner discovered that one of the partner hospitals had violated the law while processing patient data. However, by the end of 2017, Suleiman signed agreements with four major NHS hospitals.

November 8, 2018, Google announced the creation of its own division of Google Health. Five days later, it was announced that DeepMind Health should be included in the parent unit.Apparently, DeepMind no one warned. According to the documents we received upon request in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act, DeepMind notified the partner hospitals of this change in only three days. The company declined to say when discussions about the merger began, but said that the short gap between the notice and the public announcement was in the interest of transparency. Suleiman wrote in 2016 that “at no stage will patient data be associated with or associated with Google’s accounts, products, or services.” Looks like his promise was broken. (Responding to questions from our publication, DeepMind said that "at this stage, none of our contracts went to Google, and this is possible only with the consent of our partners. The fact that Streams has become a service of Google does not meanthat patient data ... may be used in other Google products or services. ")

Google annexation has angered the staff of DeepMind Health. According to people close to this unit, upon completion of the takeover, many employees plan to quit. One member of the IRP, Mike Bracken, has already left. According to several people familiar with the event, Bracken left in December 2017 because of fears that the “control commission” is more like a showcase than genuine supervision. When Bracken asked Suleiman whether he would be accountable to the commission and equalize their powers with non-executive directors, Suleiman only grinned. (A spokesperson for DeepMind said that he "did not remember" about such an incident). Julian Huppert, head of the IRP, argues that the group provided “more radical control” than Bracken expected, as members could speak openly and were not bound by the duty of confidentiality.

This episode shows that DeepMind peripherals are vulnerable to Google. DeepMind said in a statement: "We all agreed that it makes sense to combine these efforts in a joint project with a more powerful resource." The question arises whether Google will apply the same logic to the work of DeepMind on a strong AI.

From the outside it seems that DeepMind has achieved great success. She has already developed software that can learn to perform tasks at a superhuman level. Hassabis often mentions Breakout, the video game for the Atari console. The Breakout player controls the platform at the bottom of the screen and reflects the ball, which bounces off the blocks above, collapsing from a strike. A player wins when all blocks are destroyed. Loses if he misses the ball. Without human instructions, DeepMind not only learned how to play the game, but also developed a strategy for launching the ball into the space above the blocks, where it jumps for a long time and earns a lot of points without effort from the player. According to Hassabis, this demonstrates the strength of learning with reinforcements and the supernatural abilities of computer programs DeepMind.

An impressive demonstration. But Hassabis is missing something. If the virtual platform is moved at least a couple of pixels up, the program will fail. The skill acquired by DeepMind is so limited that it cannot even respond to tiny changes in the environment that a person can take into account — at least not without thousands of additional rounds of training. But such changes are an integral part of the surrounding reality. For a diagnostician there are no two identical organs of the body. For a mechanic, no two engines can be configured equally. Therefore, systems trained in virtual space may have difficulty starting in real conditions.

The second catch that DeepMind rarely talks about is that success in virtual environments depends on the presence of a reward function: a signal that allows a neural network to measure its progress. The program sees that a multiple rebound from the back wall increases the score. The main part of the development of AlphaGo was to create a reward function compatible with such a complex game. Unfortunately, the real world does not offer simple rewards. Progress is rarely measured by individual points. Even if they exist, the task is complicated by political problems. Setting the reward signal to improve climate (concentration of CO₂ in the atmosphere) is contrary to the reward signal for oil companies (stock price) and requires a compromise with many people of conflicting motivations. Remuneration signals are usually very weak.The human brain rarely receives clear feedback on the success of a task during its execution.

DeepMind has found an effective way to learn, using a huge amount of computing resources. The AlphaGo program has been trained for thousands of years of playing time before it understood something. Many AI specialists suspect that this method will not work for tasks that offer weaker rewards. DeepMind acknowledges the problem. She recently focused on StarCraft 2, a strategic computer game. Decisions made at the beginning of the game have much later consequences, which is closer to the confusing and overdue feedback in the real world. In January, DeepMind won some of the best players in the world in the demo version, which, although it was very limited, was still impressive. Her programs also began to explore reward functions based on feedback from a human teacher. But by cycling the teacher,you risk losing the economies of scale and speed offered by pure computer processing.

The current and former researchers of DeepMind and Google, who asked to remain anonymous due to strict non-disclosure agreements, also expressed skepticism that using such methods DeepMind can create a strong AI. In their opinion, the emphasis on high performance in virtual environments makes it difficult to solve the problem with the reward signal. And yet the game approach underlies DeepMind. The company has an internal leaderboard where programs from competing programming teams compete for virtual domains.

Hassabis always perceived life as a game. Most of his career is devoted to game development, and most of his free time is spent on playing practice. In DeepMind, he chose games as the primary means for creating a strong AI. Like its software, Hassabis can only learn from experience. People can forget about the original task, since DeepMind has already invented some useful medical technology and surpassed the class of the greatest players in board games. These are significant achievements, but not those which the founder of the company craves. However, he still has a chance to create a strong AI right under the nose of Google, but outside the control of the corporation. If this works out, Demis Hassabis will win the most difficult game.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/444234/

All Articles