Winnti: Supply Chain Attack - Asian Game Developers at Gunpoint

Not for the first time, attackers attack the gaming industry, compromise developers, add backdoors to the game build environment, and then distribute malicious software in the guise of legitimate software. In April 2013, Kaspersky Lab reported a similar incident. This attack is attributed to a cyber group called Winnti.

Recently, the attention of ESET experts attracted new attacks on the supply chain. Two games and one gaming platform were compromised to introduce a backdoor. These attacks are aimed at Asia and the gaming industry, behind them again stands the Winnti group.

Despite the different configurations of the malware, the three compromised software products included the same backdoor code and were launched using an identical mechanism. Now there are no backdoors in two products, but one is still spreading in a trojanized version - ironically, this game is called Infestation, which is released by the Thai company Electronics Extreme. We are trying to contact the developer from the beginning of February, but so far to no avail.

')

Let us examine how the malicious payload is implemented, and then we will consider the backdoor in detail.

The payload code runs during the execution of a trojanized executable file. Immediately after the PE entry point, the standard C initialization invocation call (

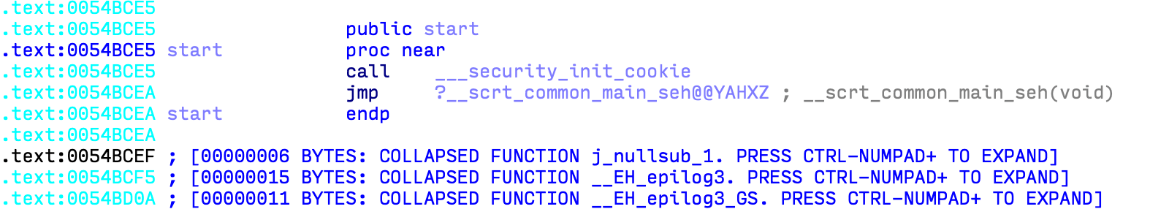

Figure 1. Net entry point to the executable file

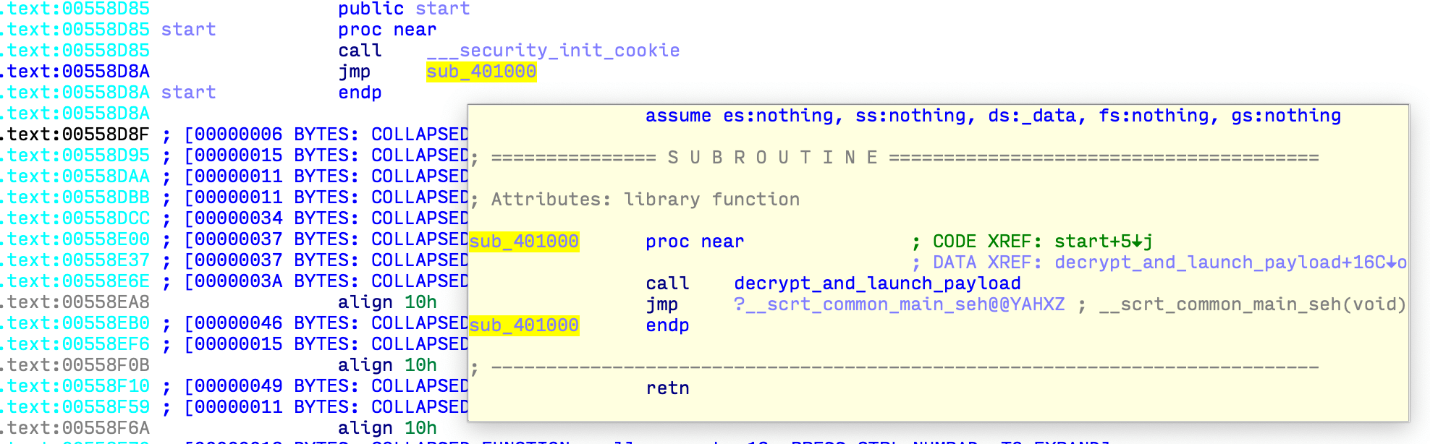

Figure 2. Entry point of a compromised executable file

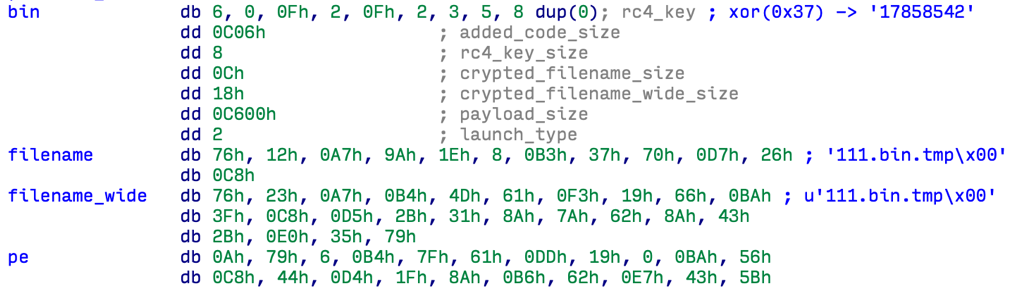

The code added to the executable file decrypts and runs the backdoor in RAM before resuming the normal execution of the C Runtime initialization code and the subsequent host application code. The built-in payload has a special structure, shown in the figure below, which is interpreted by the added decompression code.

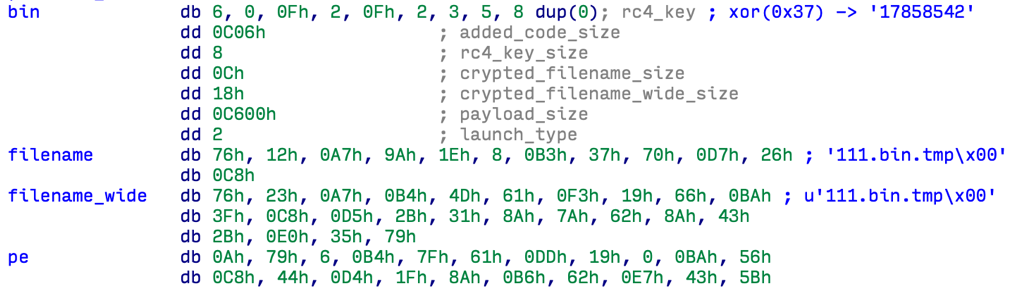

Figure 3. Embedded payload structure

It includes the RC4 key (encrypted XOR with 0x37), which is used to decrypt the file name and the embedded DLL file.

The actual malicious payload contains only 17 Kbytes of code and data.

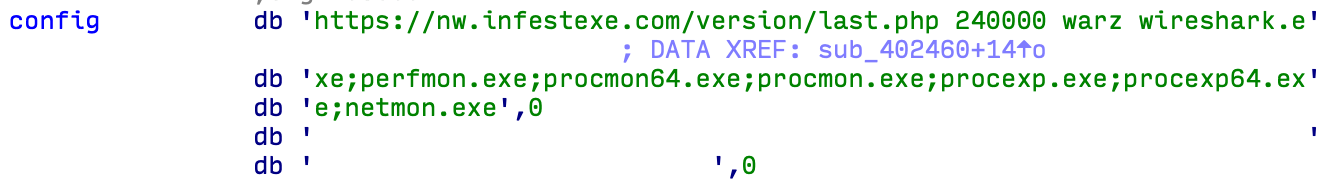

The configuration data shown in the figure below is a list of strings separated by spaces.

Figure 4. Payload configuration data

The configuration consists of four fields:

We identified five payload versions:

In the first three variants, the code was not recompiled, but these configurations were edited in the DLL file itself. The rest of the content is byte-copy.

Domain names are chosen in such a way as to resemble the sites of developers of compromised applications. The top-level domain is configured to redirect to the corresponding legitimate site using the Namecheap service, while the subdomain points to the malicious C & C server.

At the time of writing this post, none of the domains are available, C & C servers do not respond.

The bot ID is generated from the MAC address of the machine. The backdoor sends information about the machine to the C & C server, including the user name, computer name, Windows version, and system language, and then waits for commands. The data is encrypted with XOR using the “

A simple backdoor supports only four commands that can be used by attackers:

-

-

-

-

Team names speak for themselves. They allow attackers to launch additional executable files from a given URL.

Perhaps the last command is less obvious.

After launching the payload, a value is requested from the registry and, if specified, execution is canceled. Perhaps attackers are trying to reduce the load on their C & C servers by avoiding callbacks from victims who are not of interest.

According to telemetry, one of the second stage payloads sent to the victims is Win64 / Winnti.BN. As far as we can tell, the dropper of this malicious program is loaded via HTTP from

- cscsrv.dll

- dwmsvc.dll

- iassrv.dll

- mprsvc.dll

- nlasrv.dll

- powfsvc.dll

- racsvc.dll

- slcsvc.dll

- snmpsvc.dll

- sspisvc.dll

The samples we analyzed were quite large - about 60 MB. However, this is only visible, since the actual size or PE file is from 63 to 72 KB, depending on the version. A lot of clean files are simply added to malicious files. This is probably what makes the component dump and install a malicious service.

After the service starts, it adds the

The latest versions of malware include an auto-update mechanism using the C & C server

Let's start with those who are definitely not targeted by the campaign. At the beginning of the payload, the malware checks whether the system language is Russian or Chinese (see the figure below). In the case of a positive response, the program stops working. It is impossible to bypass this exception - computers with these language settings are not fundamentally interesting for an attacker.

Figure 5. Checking the language before starting the payload

According to telemetry, most of the infections occurred in Asia, primarily Thailand. Given the popularity of the compromised application, which is still distributed by the developer, it is not surprising if the number of victims is in the tens and hundreds of thousands.

Supply chain attacks are difficult to detect on the user side. It is impossible to analyze all running software, as well as all recommended updates. The user trusts developers by default and assumes that their files do not contain malicious code. This is probably why several cyber groups target attacks against software vendors — a compromise will create a botnet whose size is comparable to the popularity of trojanized software. This tactic has a reverse side - when the scheme is revealed, the attackers will lose control of the botnet, and users will be able to clean the system by installing the next update.

The motives of the Winnti cyber group are currently unknown. Perhaps attackers are looking for financial gain or are planning to use a botnet as part of a larger operation.

ESET products detect the threat as Win32 / HackedApp.Winnti.A, Win32 / HackedApp.Winnti.B, the payload as Win32 / Winnti.AG, the second stage as Win64 / Winnti.BN.

Indicators of compromise are available by reference .

Recently, the attention of ESET experts attracted new attacks on the supply chain. Two games and one gaming platform were compromised to introduce a backdoor. These attacks are aimed at Asia and the gaming industry, behind them again stands the Winnti group.

Three cases, one backdoor

Despite the different configurations of the malware, the three compromised software products included the same backdoor code and were launched using an identical mechanism. Now there are no backdoors in two products, but one is still spreading in a trojanized version - ironically, this game is called Infestation, which is released by the Thai company Electronics Extreme. We are trying to contact the developer from the beginning of February, but so far to no avail.

')

Let us examine how the malicious payload is implemented, and then we will consider the backdoor in detail.

Payload implementation

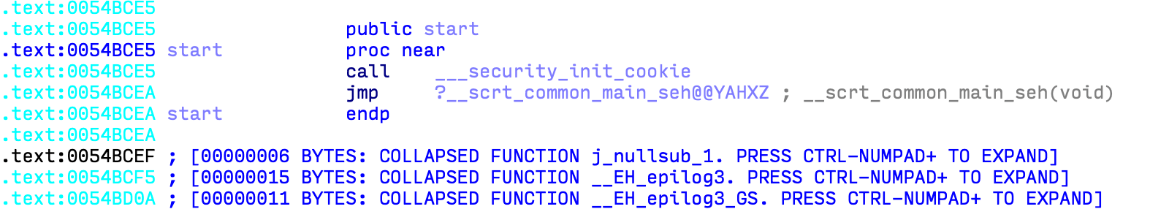

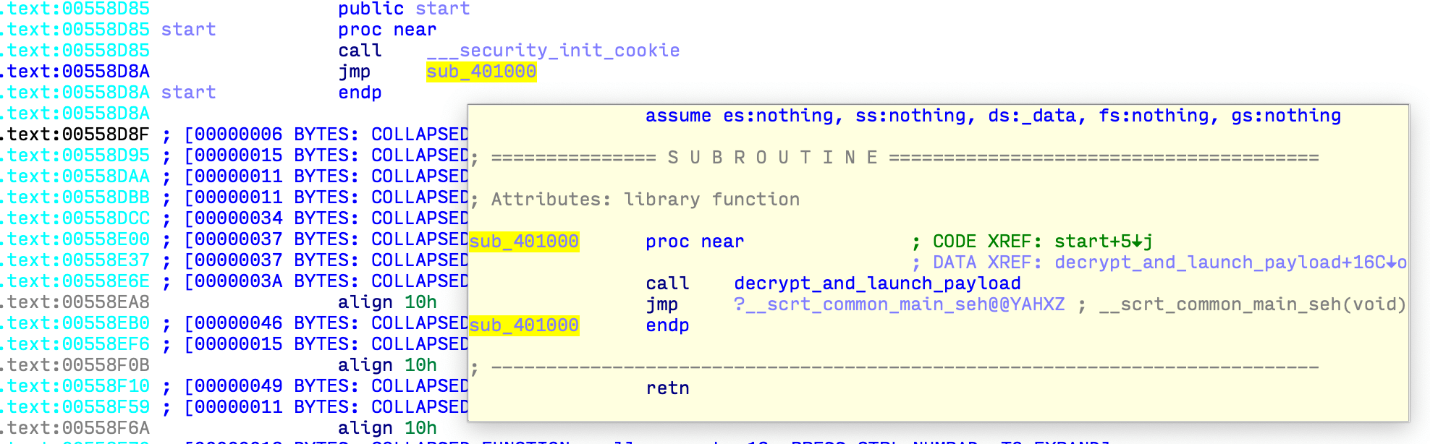

The payload code runs during the execution of a trojanized executable file. Immediately after the PE entry point, the standard C initialization invocation call (

__scrt_common_main_seh in the figure below) is intercepted to launch the malicious payload before anything else (Figure 2). This may indicate that the attackers changed the configuration of the assembly, and not the source code itself.

Figure 1. Net entry point to the executable file

Figure 2. Entry point of a compromised executable file

The code added to the executable file decrypts and runs the backdoor in RAM before resuming the normal execution of the C Runtime initialization code and the subsequent host application code. The built-in payload has a special structure, shown in the figure below, which is interpreted by the added decompression code.

Figure 3. Embedded payload structure

It includes the RC4 key (encrypted XOR with 0x37), which is used to decrypt the file name and the embedded DLL file.

Malicious payload

The actual malicious payload contains only 17 Kbytes of code and data.

Configuration

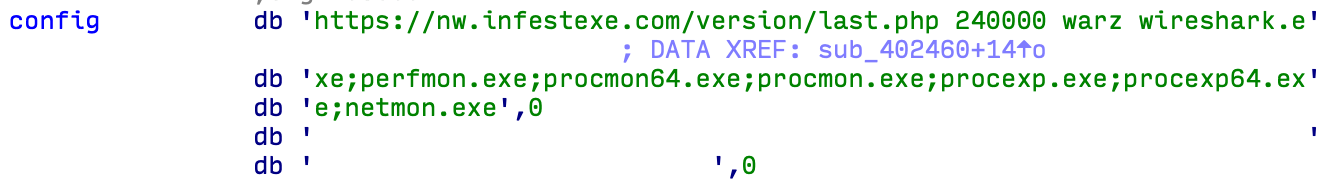

The configuration data shown in the figure below is a list of strings separated by spaces.

Figure 4. Payload configuration data

The configuration consists of four fields:

- URL of the C & C server manager.

- The variable (t) used to determine the timeout in milliseconds before continuing execution. The waiting time is selected in the range from 2/3 to 5/3 t randomly.

- String identifying the campaign.

- A list of executable file names, separated by semicolons. If any of them work, the backdoor stops its execution.

We identified five payload versions:

In the first three variants, the code was not recompiled, but these configurations were edited in the DLL file itself. The rest of the content is byte-copy.

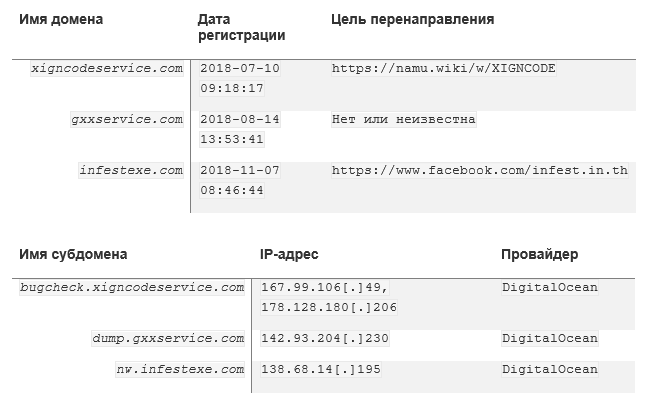

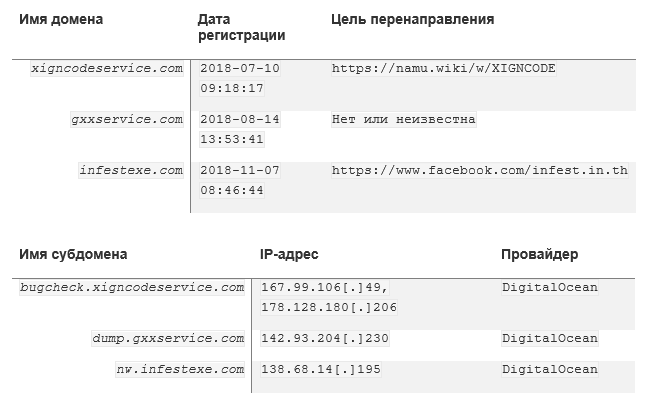

C & C infrastructure

Domain names are chosen in such a way as to resemble the sites of developers of compromised applications. The top-level domain is configured to redirect to the corresponding legitimate site using the Namecheap service, while the subdomain points to the malicious C & C server.

At the time of writing this post, none of the domains are available, C & C servers do not respond.

Study report

The bot ID is generated from the MAC address of the machine. The backdoor sends information about the machine to the C & C server, including the user name, computer name, Windows version, and system language, and then waits for commands. The data is encrypted with XOR using the “

*&b0i0rong2Y7un1 ” key and encoded with base64. Data received from the C & C server is encrypted using the same key.Teams

A simple backdoor supports only four commands that can be used by attackers:

-

DownUrlFile-

DownRunUrlFile-

RunUrlBinInMem-

UnInstallTeam names speak for themselves. They allow attackers to launch additional executable files from a given URL.

Perhaps the last command is less obvious.

UnInstall does not remove the malware from the system. In the end, it is built into the legitimate executable file that will still run. Instead of deleting something, the command disables the malicious code, setting the value to 1 for the registry key:HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\ImageFlagAfter launching the payload, a value is requested from the registry and, if specified, execution is canceled. Perhaps attackers are trying to reduce the load on their C & C servers by avoiding callbacks from victims who are not of interest.

Second phase

According to telemetry, one of the second stage payloads sent to the victims is Win64 / Winnti.BN. As far as we can tell, the dropper of this malicious program is loaded via HTTP from

api.goallbandungtravel[.]com . We saw that it was installed as a Windows service and as a DLL in C:\Windows\System32 , using the following file names:- cscsrv.dll

- dwmsvc.dll

- iassrv.dll

- mprsvc.dll

- nlasrv.dll

- powfsvc.dll

- racsvc.dll

- slcsvc.dll

- snmpsvc.dll

- sspisvc.dll

The samples we analyzed were quite large - about 60 MB. However, this is only visible, since the actual size or PE file is from 63 to 72 KB, depending on the version. A lot of clean files are simply added to malicious files. This is probably what makes the component dump and install a malicious service.

After the service starts, it adds the

.mui extension to its DLL .mui and decrypts it with RC5. The decrypted MUI file contains a position-independent code with an offset of 0. The RC5 key is obtained from the hard disk serial number and the string “ f@Ukd!rCto R$. ". We could not get either the MUI files or the code that installs them first. Thus, the exact purpose of the malicious service is unknown to us.The latest versions of malware include an auto-update mechanism using the C & C server

http://checkin.travelsanignacio[.]com . This server served the latest version of MUI files encrypted with a static RC5 key. During our research, this C & C server did not respond.Goals

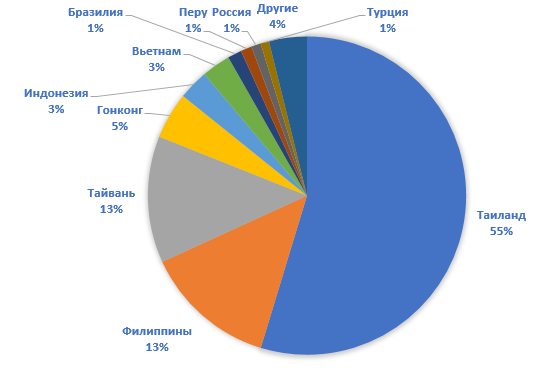

Let's start with those who are definitely not targeted by the campaign. At the beginning of the payload, the malware checks whether the system language is Russian or Chinese (see the figure below). In the case of a positive response, the program stops working. It is impossible to bypass this exception - computers with these language settings are not fundamentally interesting for an attacker.

Figure 5. Checking the language before starting the payload

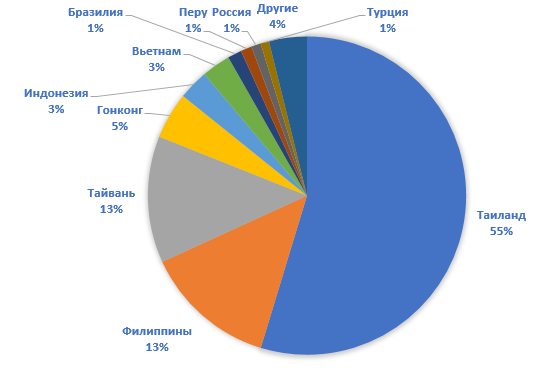

Distribution statistics

According to telemetry, most of the infections occurred in Asia, primarily Thailand. Given the popularity of the compromised application, which is still distributed by the developer, it is not surprising if the number of victims is in the tens and hundreds of thousands.

Conclusion

Supply chain attacks are difficult to detect on the user side. It is impossible to analyze all running software, as well as all recommended updates. The user trusts developers by default and assumes that their files do not contain malicious code. This is probably why several cyber groups target attacks against software vendors — a compromise will create a botnet whose size is comparable to the popularity of trojanized software. This tactic has a reverse side - when the scheme is revealed, the attackers will lose control of the botnet, and users will be able to clean the system by installing the next update.

The motives of the Winnti cyber group are currently unknown. Perhaps attackers are looking for financial gain or are planning to use a botnet as part of a larger operation.

ESET products detect the threat as Win32 / HackedApp.Winnti.A, Win32 / HackedApp.Winnti.B, the payload as Win32 / Winnti.AG, the second stage as Win64 / Winnti.BN.

Indicators of compromise are available by reference .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/443416/

All Articles