Why when learning one language you should not look at others

Suppose you are interested in this strange word. Where do you refer: to a translator or an explanatory dictionary? I think the second option is preferable.

Picture-tip and word translation

absquatulate - To leave quickly or in a hurry; to depart, flee.

Speaking in Russian, this word means “to run away, to leave in a hurry”

I think that most of the readers did not understand what I am leading now. Perhaps the example is not good enough, but good examples of the place just below the text of the article.

Habr, like the IT community as a whole, is inextricably linked to English for a number of reasons. Nevertheless, when learning languages (not only English, although all the examples here are taken from it), many face such a difficulty: it is too difficult to remember everything. This word seems to mean “water”, and after it comes “melon”. Water melon, definitely. It seems that with examples I have not really.

')

So, let's get closer to the essence, to the question that is listed in the title.

Many language learners are used to doing this according to this scheme:

- We see something unfamiliar

- We are looking for a translation

- Remember

- Safely forget

Oops. Something went wrong. Let's see why our brain refuses to accept new information in this form. Here, you see the word spring . Suppose that every reader absolutely does not understand English and does not know what it means. Translator will give you a huge amount of information (at least, Google Translate will give you 54 translation options), which you cannot master completely. Absolutely different words (how are “spring” and “jailbreak” related?) That do not tally with each other. And then, in order to avoid wasting time, you look at a couple of values and then you will not understand what coil spring is .

The main problem is that we are trying to “pull” the model of another language into our native language, matching words not with their meaning, but with other words, creating an unnecessary layer that forces us to store more information. The brain protests against the fact that spring is <spring array of 54 Russian words>.

Even if you miraculously remember all this, then imagine how much this double transformation will slow you down. word >> word >> meaning. Add to this an account of the context in which you cannot translate everything on the go, and get a wonderful non-working scheme “How I spent 4 years to understand the title of the article on Medium”.

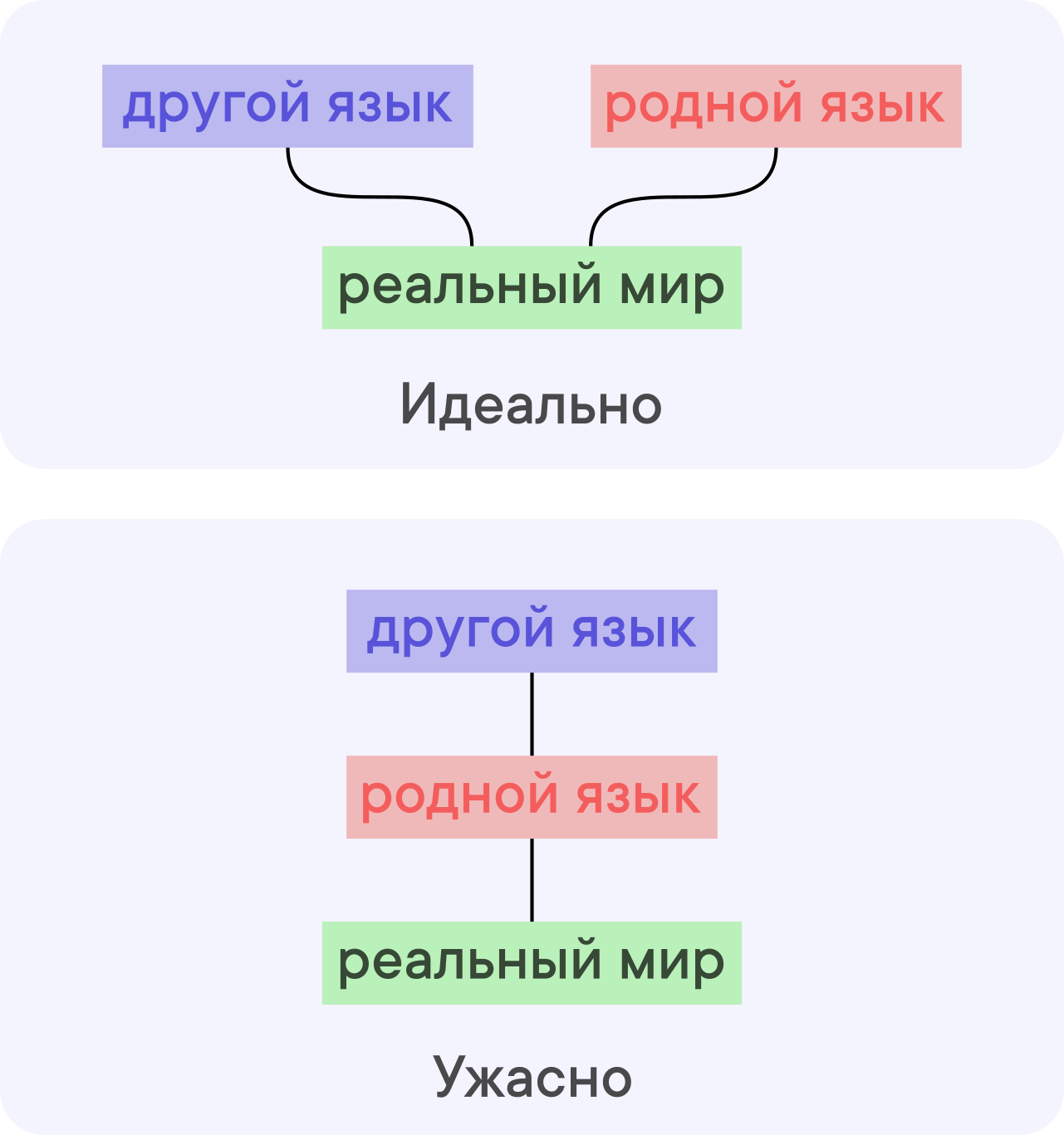

So, the adoption of new information should go according to this scheme:

- We see something unfamiliar

- We are looking for value (you can in your native language, but preferably in the original language)

- Remember

Why is this approach better? Because you can immediately understand the structure that you have read and, in your own words, convey it in your own language if necessary. If you do not need it, you will not need your native language. The difference is more visible in the diagram:

Despite the fact that the number of connections has not changed, they are grouped in the upper scheme so that the actual value with which our brain will work will always be in one step from any language, and vice versa. Using the lower scheme, we condemn ourselves to the eternal translation of one language into another, to translation errors, to the incoherence of the information that we get from the material in which a foreign language is used.

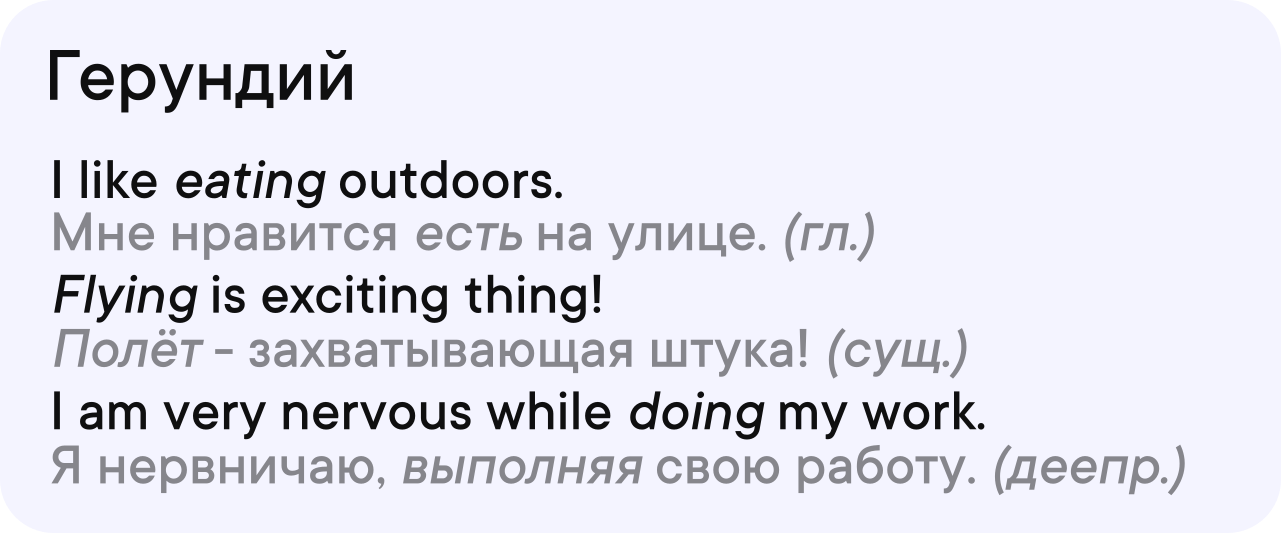

Moreover, this is true not only for individual words, but also for grammatical structures, for any element of the language. For example, you should not try to compare English gerund ( English Wikipedia ) with a specific part of speech in Russian - because the closest Russian relative to gerund is a verbal noun that does not accurately reflect its meaning.

However, this approach is used, for example, in various cards for learning a language - they often have a large foreign word, and most of the space is taken by the image of the subject. But we still get bogged down in the opinion that a translator is constantly needed to learn a language. Sure, sometimes it may be needed, but much less frequently than we use it. Those for whom a foreign language is a native have not learned another in order to associate theirs with it. They simply connected in their heads a construction of words with objects and with other convenient representations. They do not memorize 54 translations of the word “spring”; they simply attach associations to it, creating a specific language model. And for them it looks logical.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/443082/

All Articles