Impossible pan and other Penrose tiles wins

In 1974, the British mathematician Roger Penrose created a revolutionary set of tiles that can be used to fill an infinite plane with a never repeating pattern. In 1982, the Israeli crystallographer Daniel Shechtman discovered a metal alloy whose atoms were lined up in a manner never before encountered in materials science. Penrose achieved widespread public recognition, which is rare for mathematicians. Shechtman received the Nobel Prize. Both scientists challenged human intuition and changed the basics of understanding the structure of nature, finding that infinite variability can occur even in a highly ordered environment.

In the foundation of their discoveries lies the “forbidden symmetry,” so named because it contradicts the deep-rooted connection between symmetry and repeatability. Symmetry is based on the axes of reflection - everything that is on one side of the line is duplicated on the other. In mathematics, this relationship is expressed by the patterns of space tiling. Symmetrical shapes, such as rectangles and triangles, can fill a plane without gaps and overlays, creating a constantly repeating pattern. The repeating patterns are called “periodic” and they are said to have “transfer symmetry”. If you move the pattern (pattern) from place to place, it will look the same.

Being a bold and ambitious scientist, Penrose was more interested not in the same patterns and repeatability, but in infinite variability. More specifically, he was interested in "aperiodic" tiling, that is, sets of figures that can fill an infinite plane without gaps and overlays, and the tiling pattern is never repeated. It was a difficult task because he couldn’t use figures (tiles) with two, three, four or six axes of symmetry — rectangles, triangles, squares or hexagons — because on an infinite plane they would create periodic or repeating patterns. That is, he needed to use figures that were thought to leave gaps when filling the plane — figures that have forbidden symmetry.

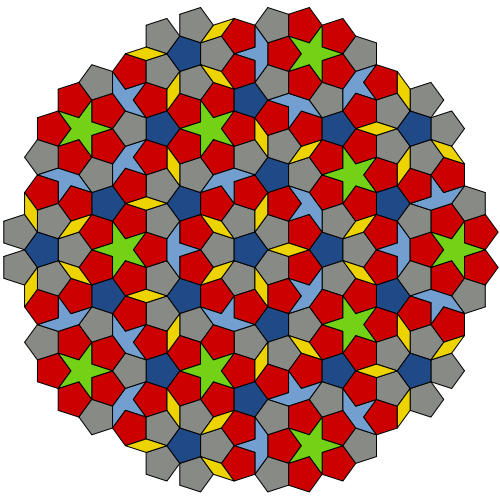

To create his own plane of non-repeating patterns, Penrose turned to five-axis symmetry — a pentagon, in particular, because, according to him, pentagons are “just a pleasure to look at.” Notable in the Penrose figures was that although he obtained these figures from the lines and corners of the rectangles, they did not leave any ugly passes. They closely adjoined to each other, bending and turning on a plane, always being close to repeatability, but never reaching it.

')

The Penrose mosaic has captured public attention for two main reasons. First, he found a way to generate infinitely changing patterns of all of the two types of shapes. Secondly, his tiles were simple, symmetrical figures, which themselves showed no signs of unusual properties.

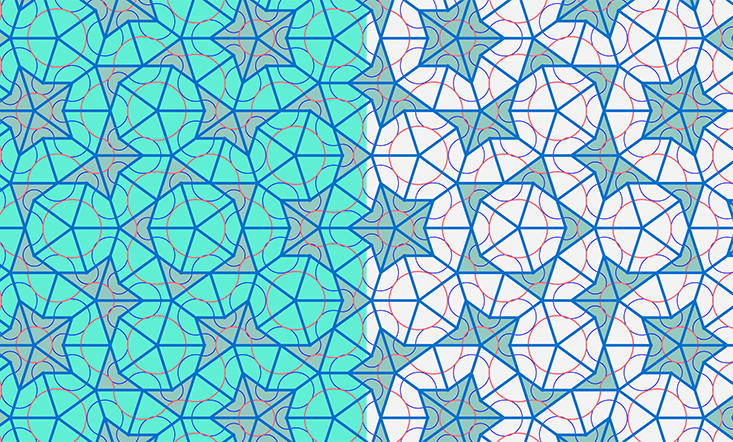

Penrose created several varieties of his aperiodic sets of figures. One of the most famous is called "serpent" and "dart". The “kite” looks like a children's kite, and the “dart” looks like a simplified contour of a stealth bomber. Both are clearly divided along the axes of symmetry and each of them has simple symmetrical arcs on the surface. Penrose defined one rule for placing shapes: for the "correct" placement of tiles, these arcs must match, creating unbreakable curves. Without this rule, snakes and darts can be placed in repeating patterns. If you follow this rule, then repetitions never arise. The serpent and the dart endlessly fill the plane, dancing around their five axes, creating stars and decagons, curving curves, butterflies and flowers. The figures are repeated, but new variations appear in them.

Clinical professor of mathematics Edmund Harriss from the University of Arkansas, who wrote his doctoral thesis on Penrose tiles, offers this comparison. “Imagine that you live in a world of squares. You start walking, and when you get to the end of the square, the next is exactly the same, and you know what you will see if you continue to move endlessly. ” Penrose tiles have exactly the opposite nature. “Whatever information you have, whatever part of the pattern you see, you can never predict what will happen next. There is always something that you have not seen before. "

One of the curious aspects of aperiodic plane splitting is that positioning information is somehow transmitted over long distances — Penrose tile laid in one place interferes with the placement of other tiles in hundreds (as well as thousands and millions) of tiles from it. “Local constraint somehow creates a global constraint,” says Harriss. “This suggests that on no scale will these tiles create something periodic.” You may have the choice to place, say, a "snake" in one area, or a "dart" in some remote place. Any of the tiles will work, but not both.

These tiles, which form an endless non-repeating pattern, express the Fibonacci proportion, also known as the "golden section." It is said that two numbers have a golden ratio, if the ratio of a smaller number to a larger one is the same as the ratio of a larger number to the sum of two numbers. In this case, the ratio of the area of "snake" to the area of "dart" is the golden ratio. The ratio of the long side of the "snake" to its short side is also a golden section.

Penrose tiles can also be divided into smaller versions of themselves. The “serpent” consists of two smaller “snakes” and the two halves of the “dart”. "Dart" consists of a reduced "snake" and two rug "dart". (In any correct Penrose tiling, these halves of the darts are aligned with each other. From the point of view of mathematics, this allows them to be considered whole darts.) “” - says Harriss. “If I subdivide them, I will get 2 A + B „ snakes “, and A + B „ darts “”

If you make such a substitution an infinite number of times, then you can calculate the total share of each type of tiles, as if laid out on an infinite plane. In such calculations, a repeating pattern always leads to a rational number. If the fraction is an irrational number, then this means that the pattern will never really completely repeat itself. When calculating for Penrose tiles, not only does an irrational number result, their ratio is the Fibonacci proportion — the ratio of “darts” to “snakes” is equal to the ratio of “snakes” to the total number of tiles.

Considering that the Fibonacci proportion is ubiquitous in nature - from pineapples to rabbit populations - it is even more strange that this proportion is fundamental to the paving system, which seemingly has nothing to do with the physical world. Penrose created something new in science, intriguing there that it should not work the way nature does. It was like Penrose wrote a fantastic story about a new animal species, and then a zoologist discovered this species living on Earth. In fact, Penrose tiles are associated with the golden section, with the mathematics invented by us, and with the mathematics of the world around us.

Taking up the study of forbidden symmetry, Penrose could not guess that he had become part of a shift in thinking that led to the discovery of a new field of mathematical science. In the end, symmetry is fundamental to pure mathematics and to the natural world. Astrophysicist Mario Livio called symmetry "one of the most necessary tools for deciphering the structure of nature." Nature uses squares and hexagons for the same reason as humans: they are simple, effective, and ordered. If pentagons seemed impractical even for such a simple task as filling the floor with tiles in interior design, then, of course, it was thought that they could not be used to create atoms in solid materials like crystals.

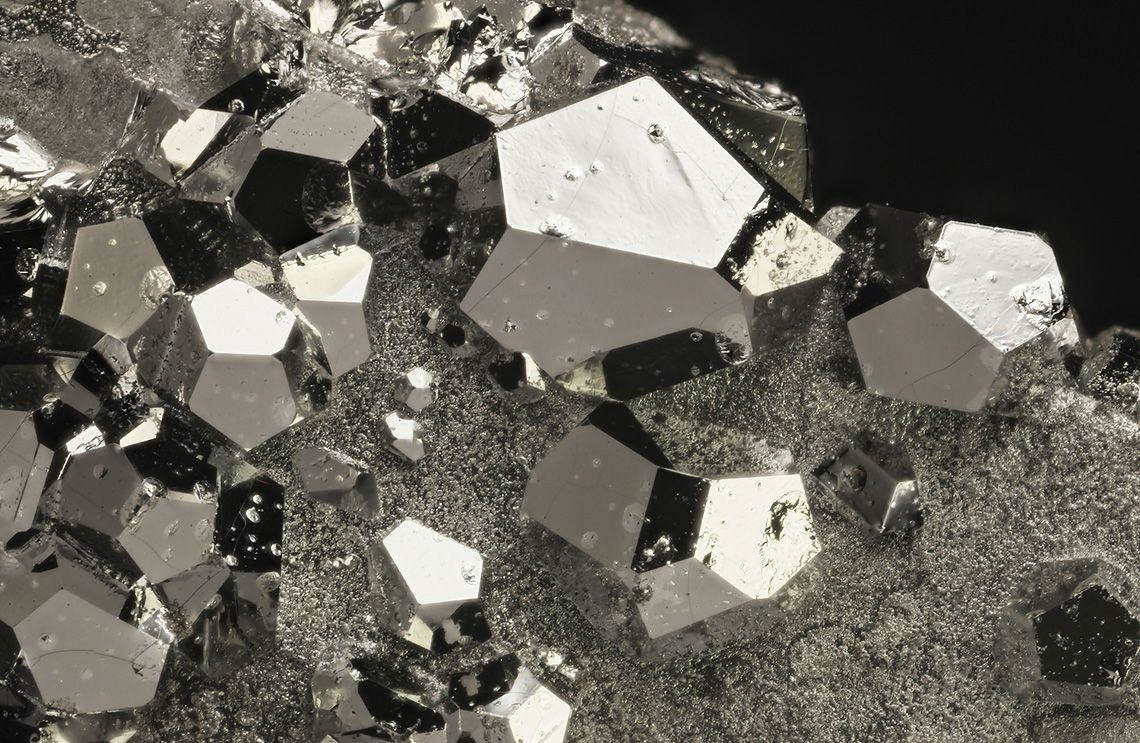

Crystals consist of three-dimensional lattices of atoms. Crystals grow by adding new atoms and expanding lattices. This happens most efficiently when atoms line up in repeating patterns. For decades, the story ended there: crystals were repetitive structures. Point.

But then, in 1982, Shechtman went on sabbatical leave from Technion University in Haifa and began working at the National Bureau of Standards. He fumbled in the laboratory with an aluminum-manganese alloy. The diffraction patterns produced by its crystal structures did not seem to resemble any of the standard symmetries known to crystallographers. In fact, the atoms lined up in those same pentagons, diamonds, "snakes" and "darts", which Penrose discovered in the world of mathematics.

“Of course, I was familiar with Penrose tiles,” says Shechtman. But he had no reason to suspect their connection with this fusion. “I did not understand what it is. Over the following months, I repeated my experiments again and again. By the end of the sabbatical, I knew exactly what it was not, but I still had no idea what it was. ”

To understand what he discovered, Shechtman, like Penrose, had to question his usual intuitive notions. He had to accept the forbidden symmetry and its pentagonal confusion with the lack of repeatability. While in Israel, he reluctantly came to recognize that he had discovered a non-repetitive crystalline atomic structure. However, no one from the world of materials science could at first attribute this discovery to crystals. Therefore, they were called "quasicrystals".

Penrose's bizarre mathematics seemed to burst out into the natural world. “For 80 years, crystals were defined as“ ordered and periodic ”structures, because all the crystals that we studied since 1912 were periodic,” explains Shechtman. “It was only in 1992 that the International Union of Crystallographers organized a committee to select a new definition for the word“ crystal ”. This new definition has become a paradigm shift for crystallography. ”

Understanding and accepting the discovery of Shechtman was hampered not only by simple inertia of thinking. Aperiodic crystal structures were not just unfamiliar - they were considered unnatural. Recall that the location of one Penrose tile can affect shapes in thousands of tiles from it — local constraints create global ones. But if a crystal is formed atom by atom, then there should not be a law of nature that creates the limitations inherent in Penrose tiles.

It turned out that crystals do not always form atom by atom. “In very complex intermetallic compounds, the elements are huge. They are not local, ”says Shechtman. When large fragments of a crystal are formed at the same time, rather than by a gradual proliferation of atoms, atoms located very far from each other can affect the mutual position, exactly as in Penrose tiles.

As with many taboos, forbidden symmetry has been recognized as one of the permissible forms of existence in nature. Quasicrystals have not only become the object of study of a new field of scientific research: it turned out that they have many useful properties arising from their unusual structure. For example, their asymmetrical configuration of atoms provides them with low surface energy, that is, little can stick to them. Thus, quasicrystal coatings began to be used in non-stick kitchen utensils. (When Penrose created his new tiles, he could not imagine that they would be used in crystallography, not to mention egg frying.) In addition, quasicrystals usually have low friction and wear, so they are ideal coatings for shaving machines and surgical instruments, or any other sharp instruments, touching the human body.

Since the structures of quasicrystals never repeat, they create unique diffraction patterns of electromagnetic radiation. Photonics researchers are interested in how they affect light transmission, reflectivity, and photoluminescence. If they are cooled, their electrical resistance drops to almost zero level. But they also absorb infrared radiation, due to which they very quickly heat to high temperatures. Because of this, they are a very useful addition to 3D printers that use plastic powder as the starting material. Shechtman explains: if a quasiperiodic powder is mixed into it and exposed to infrared radiation, then the quasi-periodic powder “heats up extremely quickly and melts the plastic particles surrounding it, which causes them to stick together”.

No one knows how the history of forbidden symmetry will end. Mathematicians continue to explore the properties of Penrose tiles. Quasicrystals remain the object of study of both fundamental and applied research. But so far this journey has been incredible. Over the past 40 years, the five-axial symmetry has evolved from impractical to valuable, from unnatural to completely natural, from forbidden to dominant. And for this transformation, we must thank the two scientists who abandoned their usual ideas in order to discover a remarkable new form of endless variations in nature.

About the author: Patchen Bars is a journalist and author from Toronto. He is currently working on a book about the relationship between pure mathematics and the natural world.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/441448/

All Articles