Analysis of recent mass DNS capture attacks

The US government and a number of leading information security companies recently warned of a series of very complex and widespread DNS hijacking attacks, which allegedly allowed hackers from Iran to receive a huge amount of email passwords and other sensitive data from several governments and private companies. But until now the details of the incident and the list of victims were kept secret.

In this article we will try to assess the scale of the attacks and trace this extremely successful cyber espionage campaign from the beginning to the cascade series of failures with key Internet infrastructure providers.

Before delving into the study, it is helpful to consider the facts disclosed publicly. On November 27, 2018, the research division of Talos at Cisco published a report describing an advanced cyber espionage campaign called the DNSpionage .

')

DNS stands for Domain Name System : a domain name system that serves as a kind of Internet phone book, translating convenient website names (example.com) to a numeric computer IP address.

Talos experts wrote that due to the DNSpionage attack, the attackers were able to obtain the e-mail account and other services of a number of government organizations and private companies in Lebanon and the United Arab Emirates by changing DNS records, so that all e-mail traffic and virtual private networks (VPN) were Redirected to an IP address controlled by hackers.

Talos reported that, thanks to DNS hijacking, hackers were able to obtain SSL encryption certificates for target domains (including webmail.finance.gov.lb), which allowed them to decrypt traffic from email and VPN accounts.

On January 9, 2019, FireEye’s security services provider published its report “The Global DNS Capture Campaign: Mass Manipulations with DNS Records,” which contains much more technical details on how the operation was performed, but few details about the victims.

At about the same time, the US Department of Homeland Security issued a rare emergency directive that instructs all US civilian federal agencies to protect their online credentials. As part of this mandate, DHS published a short list of domain names and Internet addresses that were used in the DNSpionage campaign, although the list did not go beyond what was previously reported by Cisco Talos and FireEye.

The situation changed on January 25, 2019, when information security specialists CrowdStrike posted a list of almost all IP addresses that were used in the hacker operation to date. The rest of this story is based on open data and interviews that we conducted, trying to shed more light on the true scale of this extraordinary attack that continues to this day.

"Passive" DNS

First, I took all the IP addresses mentioned in the CrowdStrike report and checked them in the Farsight Security and SecurityTrails services, which passively collect data on changes in DNS records associated with tens of millions of domains around the world.

Check back on these IP addresses made sure that in the last few months of 2018, DNSpionage hackers managed to jeopardize key components of the DNS infrastructure for more than 50 Middle Eastern companies and government agencies, including targets in Albania, Cyprus, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

For example, these “passive data” indicate that the attackers were able to intercept the DNS records of the domain mail.gov.ae , which services the e-mail of the UAE government agencies. Here are just a few other interesting domains successfully compromised during the operation:

-nsa.gov.iq: Iraq National Security Council

-webmail.mofa.gov.ae: e-mail of the UAE Ministry of Foreign Affairs

-shish.gov.al: Albanian State Intelligence Service

-mail.mfa.gov.eg: mail server of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Egypt

-mod.gov.eg: Egyptian Ministry of Defense

-embassy.ly: Libyan Embassy

-owa.e-albania.al: Outlook Web Access Portal for Albanian e-Government

-mail.dgca.gov.kw: Kuwait Civil Aviation Bureau mail server

-gid.gov.jo: Jordan General Intelligence Agency

-adpvpn.adpolice.gov.ae: Abu Dhabi Police VPN Service

-mail.asp.gov.al: email to the Albanian state police

-owa.gov.cy: Microsoft Outlook Web Access Portal for the Government of Cyprus

-webmail.finance.gov.lb: mail of the Ministry of Finance of Lebanon

-mail.petroleum.gov.eg: Egyptian Oil Ministry

-mail.cyta.com.cy: Cyprus Telecom and Internet Provider Cyta

-mail.mea.com.lb: Middle East Airlines Mail Server

Passive DNS data from Farsight and SecurityTrails also give hints when each of these domains is “captured”. In most cases, the attackers apparently changed the DNS records for these domains (later we will tell how this was done), so that they point to servers under their control in Europe.

Shortly after the start of the attack - sometimes weeks later, sometimes days or hours - the attackers were able to obtain SSL certificates for these domains from Comodo and / or Let's Encrypt certification authorities. The preparation of several attacks can be traced via crt.sh : the base of all new SSL certificates with the search function.

Let's take a closer look at one example. The CrowdStrike report mentions the IP address 139.59.134 [.] 216 (see above), on which, according to Farsight, seven different domains were hosted for many years. But in December 2018, two new addresses appeared on this address, including domains in Lebanon and - curiously enough - in Sweden.

The first one, ns0.idm.network.lb, is the server of the Lebanese Internet provider IDM . From the beginning of 2014 to December 2018, the record ns0.idm.net.lb pointed to the Lebanese IP address 194.126.10 [.] 18 . But in the screenshot from Farsight below it can be seen that on December 18, 2018, the DNS records for this Internet provider changed, redirecting traffic destined for IDM to a hosting provider in Germany (address 139.59.134 [.] 216).

Please note what other domains are on this IP address 139.59.134 [.] 216 along with the IDM domain, according to Farsight:

The DNS records of the domains sa1.dnsnode.net and fork.sth.dnsnode.net in December also changed from their legitimate Swedish addresses to the IP of the German hosting provider. These domains are owned by Netnod Internet Exchange , a major global DNS provider from Sweden. Netnod also manages one of 13 root DNS servers : a critical resource underpinning the global DNS system.

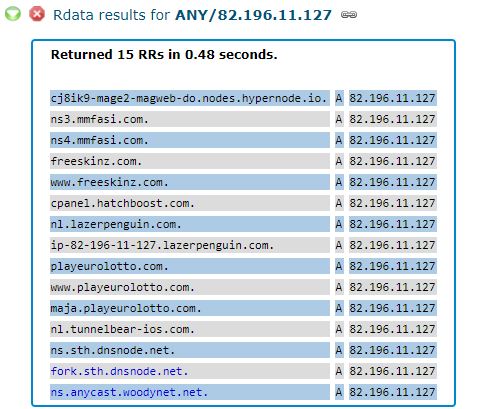

A little later, back to the company Netnod. But first, let's look at the other IP address listed in the CrowdStrike report as part of the infrastructure affected by the DNSpionage attack: 82.196.11 [.] 127 . This gold address also contains the mmfasi [.] Com domain. According to CrowdStrike, this is one of the domains of the attackers, which was used as a DNS server for some of the captured domains.

As you can see, on 82.196.11 [.] 127 another pair of Netnod DNS servers was temporarily located, as well as the ns.anycast.woodynet.net server. He is nicknamed Bill Woodcock , executive director of Packet Clearing House (PCH) .

PCH is a nonprofit organization in Northern California that also manages a large part of the global DNS infrastructure, including serving more than 500 top-level domains and a number of top-level domains in the Middle East affected by the DNSpionage operation.

Attack on recorders

On February 14th, we contacted Netnod CEO Lars Michael Yogbek. He confirmed that part of the Netnod DNS infrastructure was captured at the end of December 2018 and the beginning of January 2019, after attackers gained access to the registrar's accounts.

Yogbek cited a company statement issued on February 5. It says that Netnod found out about its involvement in the attack on January 2, after which it acted in all contact with all interested parties and customers.

“As a participant in international security cooperation, on January 2, 2019, Netnod learned that we were embroiled in this series of attacks and were attacked like MiTM (man-in-the-middle),” the statement said. - Netnod is not the ultimate goal of hackers. According to the information available, their goal is to collect accounting data for Internet services in countries outside Sweden. ”

On February 15, Bill Woodcock from PCH, in an interview, admitted to me that parts of the infrastructure of his organization had also been compromised.

After receiving unauthorized access, the hackers copied the records of the domains pch.net and dnsnode.net to the same servers of the German domain registrar Key-Systems GmbH and the Swedish company Frobbit.se. The latter is a Key Systems reseller, and part of the Internet infrastructure is the same.

Woodcock said phishing hackers lured away the credentials that PCH used to send signaling messages known as the Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP) or the "Extensible Information Provisioning Protocol ." This is a little-known interface, a kind of global DNS backend, allowing domain registrars to notify regional registries (for example, Verisign) about changes in domain records, including new domain registrations, changes and transfers.

“In early January, Key-Systems announced that outsiders had stolen their EPP interface by stealing credentials,” said Woodcock.

Key-Systems declined to comment on the story. She stated that she did not discuss the details of the business of her reseller customers.

Netnod's official statement about the attack addresses further requests to security director Patrick Voltström, who also co-owns Frobbit.se.

In correspondence with us, Voltström said that the hackers managed to send EPP instructions to various registries on behalf of Frobbit and Key Systems.

“From my point of view, it is obvious that this is an early version of a future serious attack on the EPP,” wrote Veltström. - That is, the goal was to send the right EPP teams to the registries. Personally, I am very scared of what might happen in the future. Do registries have to trust all teams from registrars? We will always have vulnerable recorders, right? ”

DNSSEC

One of the most interesting aspects of these attacks is that Netnod and PCH are loud supporters and followers of DNSSEC , technology to protect against attacks of this type that DNSpionage hackers have been able to use.

DNSSEC protects applications from tampering with DNS data by requiring a mandatory digital signature for all DNS queries for a given domain or set of domains. If the name server determines that the address record of this domain has not changed during transmission, it performs rezolving and allows the user to visit the site. But if the record has somehow changed or does not match the requested domain, then the DNS server blocks access.

Although DNSSEC can be an effective tool to mitigate such attacks, only about 20% of the main networks and sites in the world have included support for this protocol, according to an APNIC study , the online registrar of the Asia-Pacific region.

Yogbek said that the Netnod infrastructure underwent three attacks as part of the DNSpionage operation. The first two occurred in a two-week interval between December 14, 2018 and January 2, 2019 and were aimed at servers not protected by DNSSEC.

However, the third attack between December 29 and January 2 was made on the Netnod infrastructure, protected by DNSSEC and serving its own internal email network. Since the intruders already had access to the registrar systems, they managed to briefly disable this protection - at least, this time was enough to get the SSL certificates of two Netnod mail servers .

When the attackers received the certificates, they re-launched DNSSEC on the target servers, probably preparing for the second stage of the attack — redirecting mail traffic to their servers. But Yogbek says that for some reason, the attackers did not turn off DNSSEC again when they started to redirect traffic.

“Fortunately for us, they forgot to turn it off when the MiTM attack began,” he said. “If they were more qualified, they would remove DNSSEC from the domain, which they could well have done.”

Woodcock says PCH checks DNSSEC on the entire infrastructure, but not all of the company's customers have set up systems to fully implement the technology. This is especially true for customers from the Middle East who are targeted by the DNSpionage attack.

Woodcock said that the PCH infrastructure was attacked by the DNSpionage four times from December 13, 2018 to January 2, 2019. Each time, hackers used tools to intercept traffic with credentials for about one hour, and then folded and returned the network to its original state.

Watching for more than an hour would be redundant, because most modern smartphones are set to constantly check email. Thus, in just one hour, hackers were able to collect a very large amount of accounting data.

January 2, 2019 - the same day that the attack took place on the internal Netnod mail servers - the hackers directly attacked PCH, obtaining Comodo SSL certificates of two PCH domains , through which the internal mail of the company also passes.

Woodcock said that, thanks to DNSSEC, the attack was almost completely neutralized, but the hackers were able to get the email credentials of two employees who were on vacation at the time. Their mobile devices downloaded mail via WiFi at the hotel, which is why (according to the terms of the WiFi service), the hotel’s DNS servers were used, rather than systems with DNNSEC support from PCH.

“Both victims at that time were on vacation with their iPhones, and they had to go through compromised portals when they received mail,” said Woodcock. “When accessing, they had to disable our name servers, and during that time their email clients checked for new mail. Other than that, DNSSEC saved us from total capture. ”

Since PCH protects its domains with DNSSEC, the practical effect of hacking the mail infrastructure was that for about an hour no one, except for two remote employees, received any letters.

“In fact, for all of our users, the mail server was unavailable for a short period of time,” said Woodcock. - People just looked at the phone, did not see the new letters and thought: strange, I will check later. And when they checked the next time, everything worked fine. A group of our employees noticed a short-term outage of the postal service, but it didn’t become too serious a problem for the discussion to start or for someone to register a ticket. ”

But the DNSpionage hackers didn't stop it. In the mailing list for PCH clients, she said that the investigation revealed the hacking of a site with a user database on January 24th. The database contains usernames, bcrypt password hashes, emails, addresses and organizations.

"We do not see evidence that the attackers made access to the database," the report said. “Thus, we report this information for the sake of transparency and precaution, and not because we consider the data compromised.”

Advanced level

Several experts we interviewed in connection with this story mentioned the chronic problems of organizations protecting their DNS traffic. Many perceive it as a certain given, do not keep logs and do not follow changes in domain records.

Even for companies that are trying to control their DNS infrastructure for suspicious changes, some monitoring services check DNS records passively or only once a day. Woodcock confirmed that PCH relies on at least three monitoring systems, but none of them warned about hourly hijackings of DNS records that hit PCH systems.

Woodcock said PCH has since implemented its own DNS infrastructure monitoring system several times an hour, which immediately alerts you to any changes.

Yogbek reported that Netnod also strengthened monitoring and redoubled efforts to implement all the available security options for the domain infrastructure. For example, before the company did not block records for all of its domains. This protection provides additional authentication before making any changes to the entries.

“We are very sorry that we did not provide maximum protection for our customers, but we ourselves were the victim in the chain of attacks,” said Yogbek. - After the robbery, you can install the best lock and hope that now it will be harder to repeat this. I can really say that we have learned a lot from becoming a victim of this attack, and now we feel much more confident than before. ”

Woodcock is concerned that those responsible for implementing new protocols and other infrastructure services do not seriously perceive the global threat of DNS attacks. He is confident that DNSpionage hackers will crack many more companies and organizations in the coming months and years.

“The battle is on right now,” he said. “The Iranians are not conducting these attacks for a short-term effect.” They are trying to penetrate the Internet infrastructure deep enough to do what they want at any time. They want to provide themselves with as many options as possible for maneuver in the future. ”

Recommendations

John Crane is the security, stability and resiliency leader for ICANN, a non-profit organization that oversees the global domain name industry. He says that many prevention and protection methods that can make it difficult for attackers to seize domains or DNS infrastructure have been known for over a decade.

“A lot comes down to data hygiene,” said Crane. “Neither large organizations, nor the smallest business, pay attention to some very simple security methods, such as multifactor authentication. Nowadays, if you have a non-optimal protection, you will be hacked. This is the reality of today. We see much more sophisticated opponents on the Internet, and if you don’t provide basic protection, they will hit you. ”

Some of the best protection methods for organizations are:

- Use DNSSEC (both to sign and verify responses)

- Use registration features such as registry lock (Registry Lock) that help protect domain name records from being changed

- Use access control lists for applications, Internet traffic and monitoring

- Use two-factor authentication and require its use by all relevant users and subcontractors

- In cases where passwords are used, select unique passwords and consider password managers.

- Check accounts with registrars and other providers

- Monitor certificates, for example, using Certificate Transparency Logs

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/441220/

All Articles