Hall of Fame Consumer Electronics: Stories of the Best Gadgets of the Last 50 Years, Part 3

The second part of

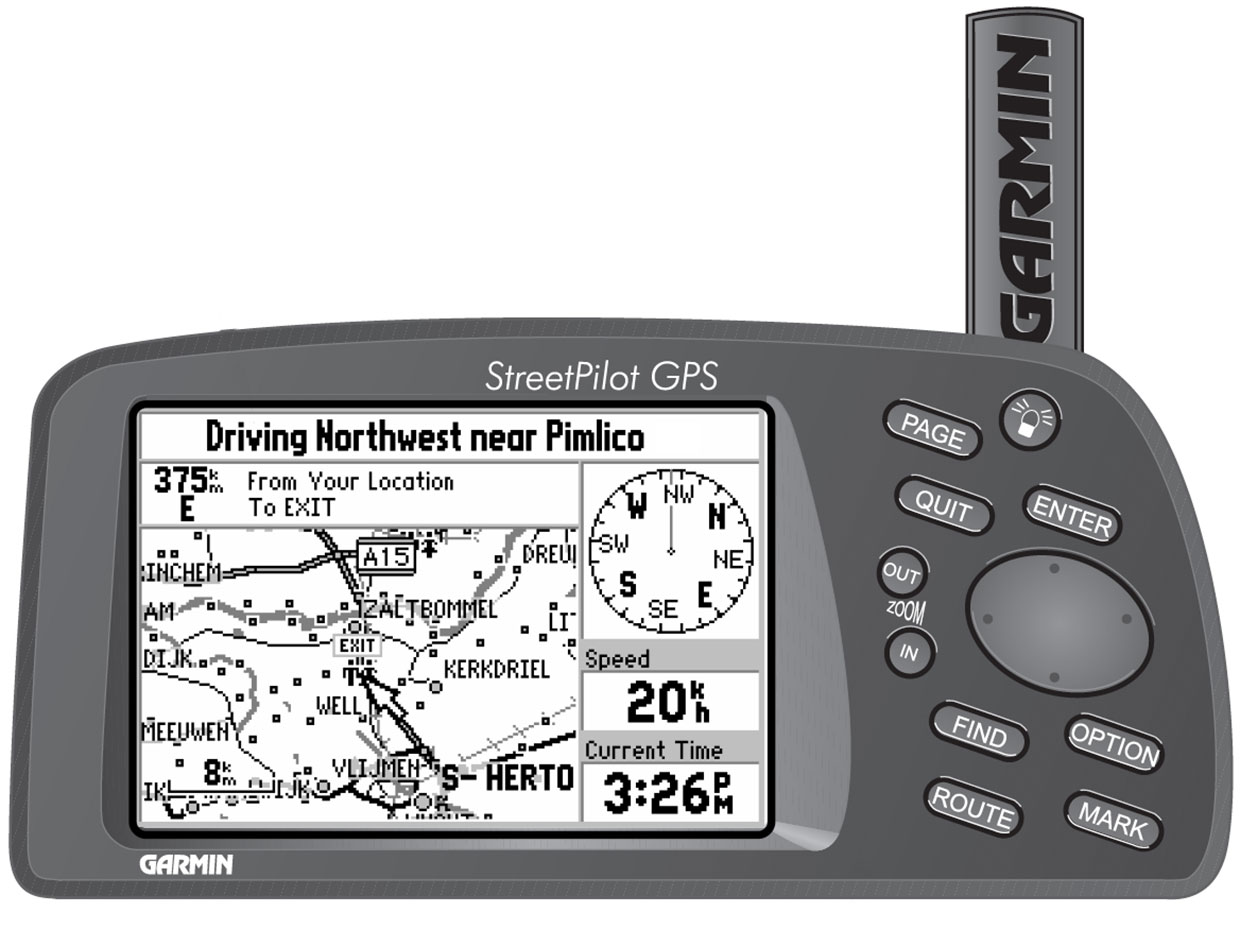

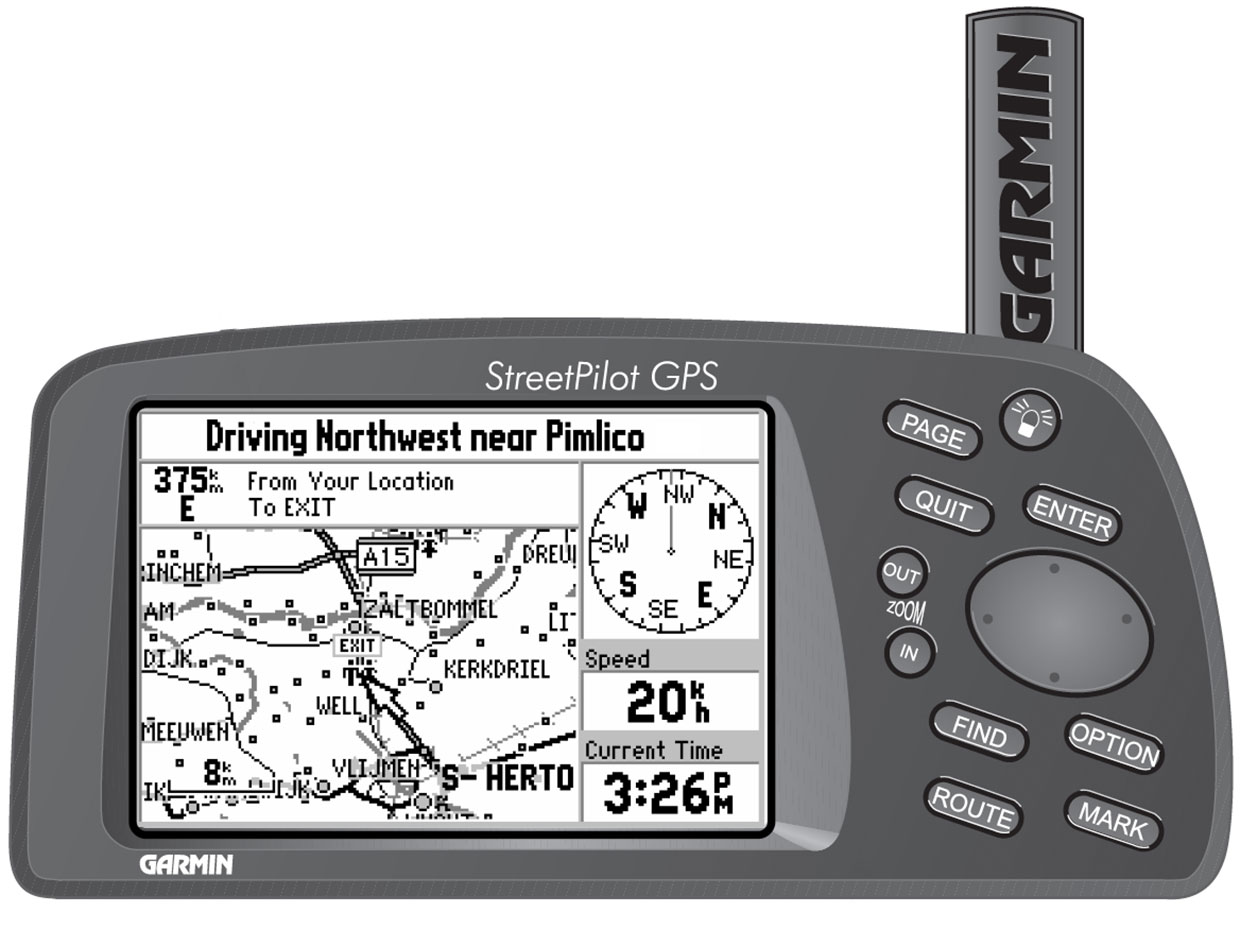

The way forward: Garmin StreetPilot, which appeared in 1998 at a price of $ 400, was one of the first practical and affordable GPS navigators

If you were born before 1980, then they probably expected you to learn how to work with cards in your teens. If you didn’t know how to get to a place, until you sat behind the wheel, you couldn’t get there.

')

There were exceptions. If you didn’t know how to drive where you wanted, you could stop and ask for directions. Or, if you had a passenger, you could rely on him (or her) as a navigator.

However, due to inconsistencies with these conditions, marriages sometimes collapsed. After the appearance of Garmin, this was no longer the case. As well as Garmin and its competitors almost destroyed the market of road atlases.

The path to such dramatic social change began within the walls of the US Department of Defense. In the early 1970s, the ministry began to create a global positioning system, GPS, but until 1983, it used it exclusively. That year, the government allowed it to be used for consumer purposes - albeit with a worsened resolution. In 1996, the government decided that GPS would be a dual-use technology - from a practical point of view, this meant that commercial companies would finally be able to obtain the same accurate data as the government and the military.

Various manufacturers rushed to make GPS systems for commercial navigation in the late 1980s, but due to poor resolution and high cost, their products weren’t scattered from the shelves. For example, Magellan Navigation introduced the first portable commercial system for GPS navigation, the NAV 1000, in 1989. Some customers were satisfied with these devices, mainly those who spent a lot of time in nature, but few pedestrians thought it necessary to purchase a device the size of a brick at a price of almost $ 3,000, which could tell what street they are on, and also give them their exact coordinates in degrees, minutes and seconds.

The use of navigation in cars promised the best prospects. Since the early 1990s, several automakers began offering GPS navigation systems, but then the high resolution was inaccessible, and the accuracy left much to be desired. And the high cost of GPS technology meant that these devices were available only in luxury models, which were sold a little.

By 1998, the cost of GPS had dropped significantly, and Garmin’s chance to earn was no worse than that of others. It was founded in 1989 under the name ProNav, and had experience creating GPS navigators for the military. Garmin was able to make a portable model at an attractive price (about $ 400), on which it was possible to download accurate street maps.

The company's first consumer product, StreetPilot, measured about 17x8x5.5 cm and weighed about 500 grams, including six AA batteries. It had a black and white LED screen of 240x160 pixels (the following year, Garmin released a model with a color screen).

The model had a 12-channel GPS receiver, and it provided positioning accuracy of no worse than 15 meters, with a maximum accuracy of 1-5 meters with differentiated GPS, when satellite signals complement signals from ground stations.

Included with StreetPilot were maps where highways between the states and within the states of the USA, rivers and lakes of the USA, Canada and Mexico, and the main streets of the main settlements were reflected. Users could buy compact discs with maps of different cities, where streets and useful establishments, such as gas stations and public catering facilities, were presented and download this data to memory cartridges (8 and 16 MB) connected to the device. Users could enter a destination address, and StreetPilot guided them in the shortest possible way. In general, StreetPilot offered the simplest version of the navigator, without information about traffic jams, and without all that can be obtained today in the free application for a smartphone. But at the time, this was a revelation.

The subsequent model, the StreetPilot III of 2002, could boast a color display with a diagonal of 3.85 ", a resolution of 305x160 and voice queries.

Garmin and its followers not only changed the way people travel by car, but also came close to devaluing for most people the ability to understand cards. And in the process, perhaps, saved several marriages.

The funnel: The original Sony Trinitron KV-1310 was introduced in Japan at a press conference on April 15, 1968.

Trinitron, unveiled by Sony in 1968, was the first significant technological breakthrough in the field of color television since such televisions first appeared on the market in the early 1950s. And, like many innovations, it was the result of the evolution of several failed projects.

The TV showed a color image when phosphor points were excited on the inside of the screen. Among the main elements of the first color TV were, if you count from the back to the front: three electronic emitters, or "guns", set by a triangle; they pointed to a barrier, a shadow mask in which holes were drilled; after that there was a screen with phosphorus.

The screen was littered with millions of tiny phosphorescent points, collected by three. When the electrons hit the dots, they emit light. In each triad there were three points, chemically created in such a way that one of them radiated red, one green, and one blue. In theory, any light visible to the human eye can be created from different combinations of red, green, and blue (red, green, blue - RGB).

Each of the three electron guns aimed only at one phosphor point in each RGB triplet. The color produced by each triplet could be chosen by highlighting the desired combination of dots with the cannons to create the desired color. The electrons from the guns ran around the screen to and fro many times a second, highlighting the necessary points and creating color images on the screen. In order to receive moving images, the screen needed to be turned on, or “painted”, many times per second. This “refresh rate” was usually at least 60 frames per second.

However, there was one problem. It was possible to aim each gun at only one point in each triplet if the guns emitted electrons by a narrow beam. But this did not happen - the “ray” of electrons looked more like splashes.

Manufacturers struggled with this with the help of a shadow mask. Holes in it passed only those electrons from each gun, which were supposed to reach the desired point in each triad. All other electrons were blocked.

Such a scheme worked, for the most part. The guns had to be perfectly aligned, and they were knocked down often enough so that they had to be periodically repaired by a professional. Moreover, shadow masks blocked a multitude of electrons that would otherwise cause the RGB triads to be phosphoressed brighter. The color screens of the televisions were not as bright as they could be, in part because of the waste of all these charged particles.

It was possible to approach improvement of quality of TVs from the different parties. For example, RCA, the world leader in the manufacture of television sets at the time, began to use rare-earth elements, which were more clearly phosphorescent. General Electric changed the location of the guns, putting them in a row (instead of a triangle) and achieved good results. A tiny band in the United States, Chromatic Television Laboratories , followed a different path. They based their approach on the idea of the famous physicist Ernest Orlando Lawrence of the University of California at Berkeley, trying to use one electronic gun, and replacing the shadow mask with a grid of charged vertical wires. This technology, called the chromatron [Chromatron], also gave a brighter picture due to the lack of a shadow mask, although Chromatic never managed to get its system to work reliably.

Sony intended not to copy other people's ideas (and not to deduct royalties). At a trade fair in 1961, funded by the Institute of Radio Engineers, one of the communities that preceded IEEE, Sony ’s directors saw a working Chromatic television. They almost on the spot agreed on a license. Sony created the TV based technology and brought it to market in 1965.

Sony's chromatrons gave an excellent color picture, but they could not be reliably produced in massive quantities, and their cost was so much more profitable from them that this business threatened to sink Sony, says Susumi Yoshida, an engineer who worked on Chromatron and Trinitron technologies. The company needed to come up with another way to produce color TVs.

Trinity Trinitron: three of the four key figures of the Trinitron project are depicted in the photo to the left; these are Susumi Yoshida, Akio Ogoshi and Senri Miyoka, who are present at the technology presentation in April 1968. One of the founders of Sony, Masaru Ibuka (right) was also an engineer, then became president of the company, and personally supervised the work of the Trinitron team.

Four leading engineers of the Trinitron Susumi Yoshida, Akio Ogoshi and Senri Miyaoka and Masaru Ibuka project. Yoshida claims that the revolutionary idea of trinitron came to him. He liked GE's approach to electronic emitters, where a linear system was used instead of a triangular one, since it was easier to reduce the rays into one point. However, he liked the idea with a single gun (as in the Zromatron), since it was cheaper. Yoshida wondered if it was impossible to place the three cathodes in one line inside one gun?

In short, it turned out that this can be done. Additional adjustments were needed, including the installation of reflective plates above the gun, which helped focus the electron beams, and create a chemical etching process to create an aperture grid that performed the same task as the grid of charged chromatron wires, and in much the same way. But the system worked, it could be mass produced at an affordable price, it was stable, it almost did not need to be professionally set up after the sale. And, more importantly, she gave a beautiful color image.

True colors: The first Trinitron KV-1210U hit the US in 1969, and its recommended price was $ 319.95, which is about $ 2,200 in 2019 prices.

Appearing in 1968, Trinitron immediately became a hit. Improved picture quality justified the high cost. In 1973, he became the first consumer electronics device to receive an Emmy Award. Sony eventually sold 280 million copies of Trinitron, first as a TV, and then as computer monitors.

And if Trinitron were just a huge step in television technology and deafening commercial success, it would have earned him a place in the Hall of Fame. But these were not his only merits. He has made Sony a first-class source of technological innovations. Its sales have helped pay for the successful period of Sony, with which for so many innovations in such a wide range of consumer products and for such a long period of several decades very few people can match. Moreover, the success of Sony was the success of Japan. Before Trinitron, most of the electronics in the country were cheap and unreliable. Trinitron has become one of the products that made Japan the source of world-class advanced electronics.

Just in time: May 9, 2015, journalists were given the opportunity to experience the Apple Watch before their official release next month. In the second fiscal quarter of the year, 4.2 million watches will be sold, making them the most popular wearable device.

Apple Watch can not be called the first smart watch. One can argue about whether this is the best smart watch. But this is, without a doubt, the best smart watches for sales - by November 2018, they already sold 33 million. And given their market share, they will continue to be the best-selling gadget of this type. Apple Watch has become one of the finest examples of how a company entered the right market with the right product at the right time. It was a great example of a timely (um) exit.

People have come up with smart watches many years ago. Comic hero Dick Tracy donned such a watch in 1946. In 1984, Seiko Epson introduced a clock synchronized with a PC. In the 90s, Timex, IBM and Samsung attempted to release an electronic watch, but they were let down by the imperfection of technology. In the 2000s, communication with the clock remained unreliable, the application was inconvenient. In 2004, Microsoft introduced the Spot smart watch; they relied on a proprietary wireless network protocol that worked on the FM frequency. It was followed by Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Vyzin Electronics and others.

In the same decade, Fitbit and other companies became pioneers in the market of fitness trackers that track carrier movement, heartbeat, sleep, and other parameters related to sleep. The next logical step seemed to be a combination of a fitness tracker and a smart watch, but fans of fitness trackers rejected the combined devices for several years after that.

Launched from kickstart: the crowdfunding phenomenon Pebble Smart Watch became an important pioneer in this whole story, but did not survive after the appearance of such a monster as Apple Watch

In 2012, Pebble Technology Corp. introduced the first successful smart watch, Pebble. They were followed by Omate TrueSmart in 2013, followed by LG, Razer, Samsung, Sony and some others. Some of the devices were combined, and for some reason people started to get used to them.

The difficulty facing each manufacturer of smart watches was that they tried to sell watches to a generation that had lost the habit of wearing them because they were used to checking with the watches on the phone.

Most manufacturers went the obvious way - made a watch that served as a supplement to the phones. It was possible to look at the clock to check the latest messages, mail or alarm clocks, without pulling the phone out of your pocket or purse.

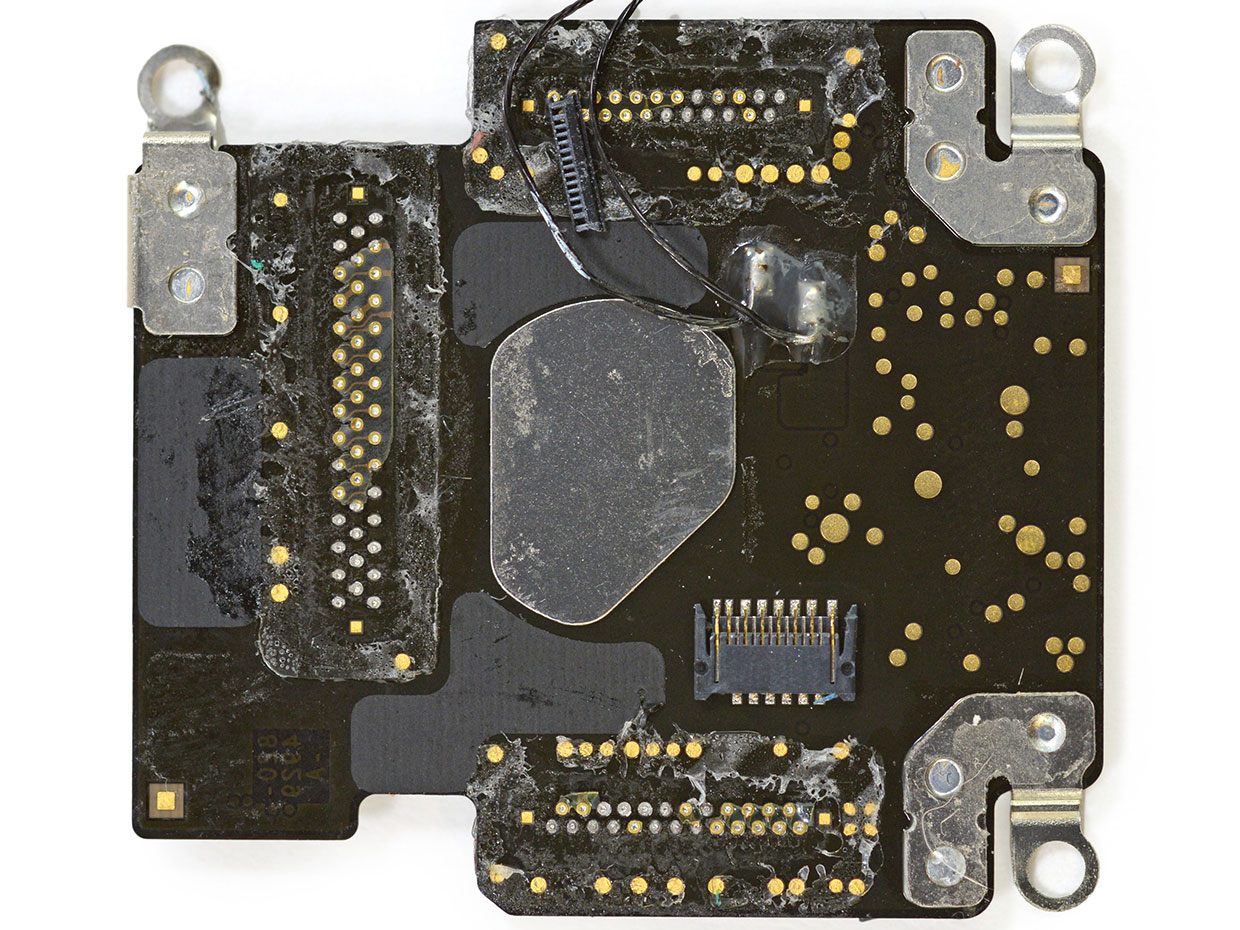

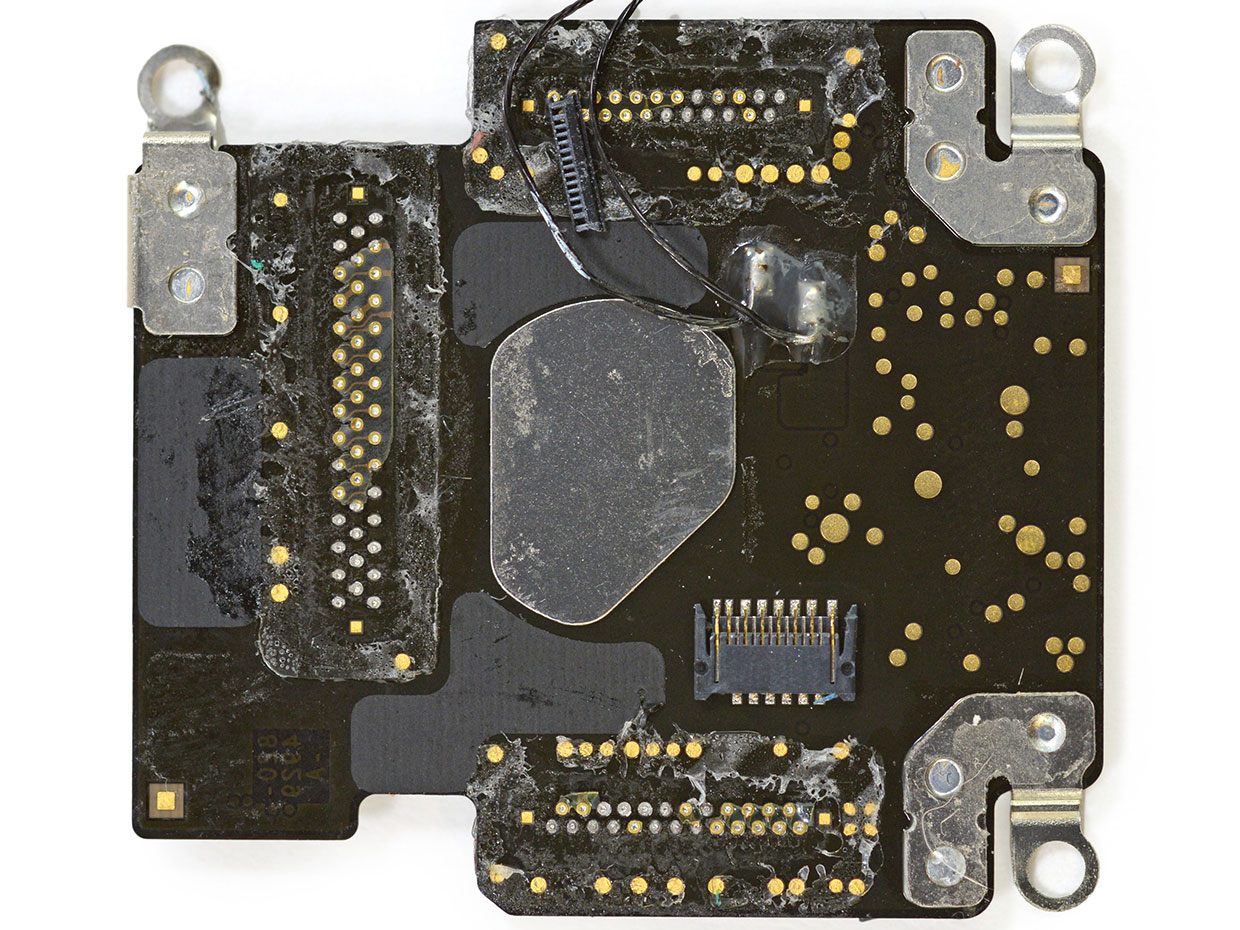

At the core of Apple: everything important in the Apple Watch was contained on the S1 module. The wrong shape in its center is the processor heatsink.

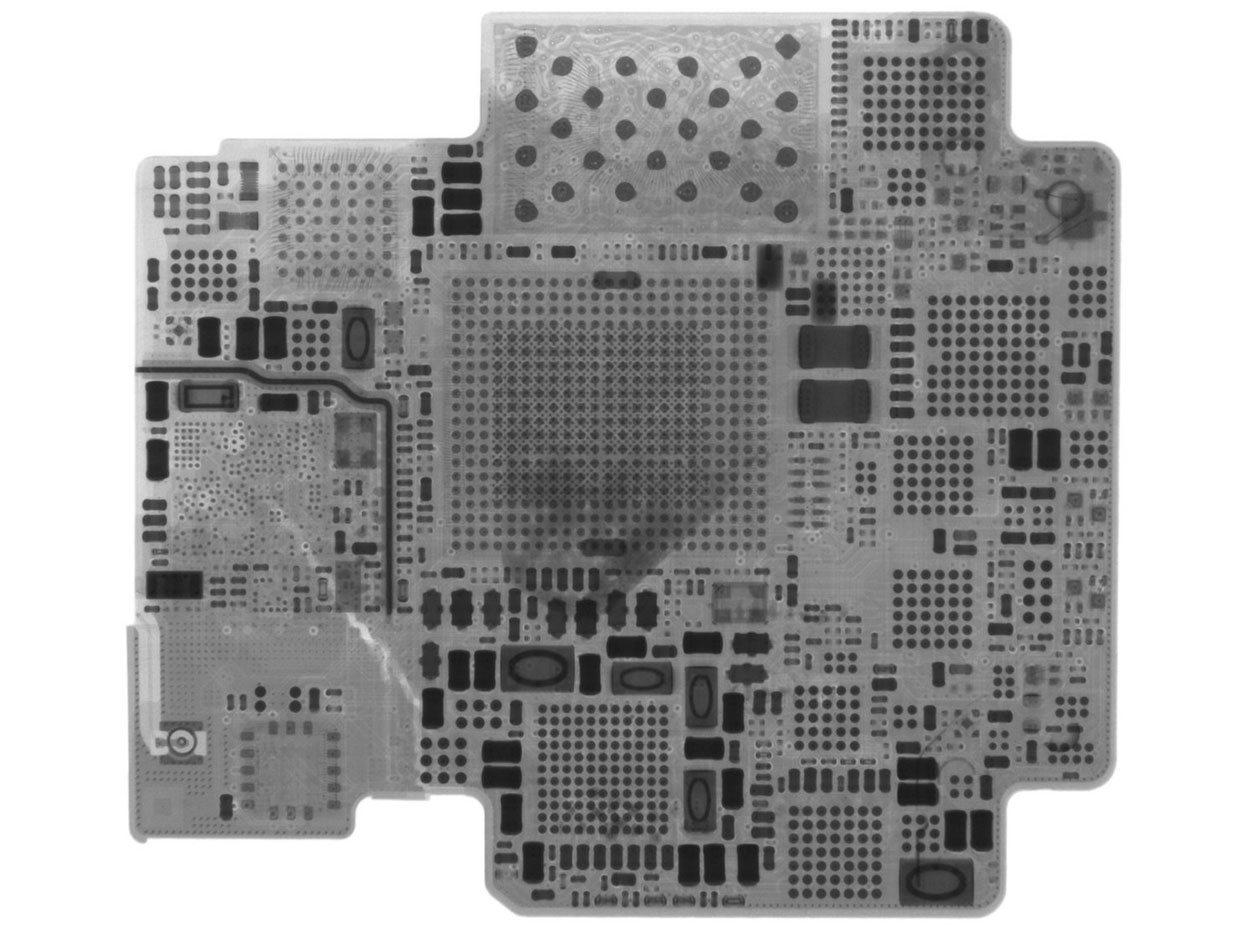

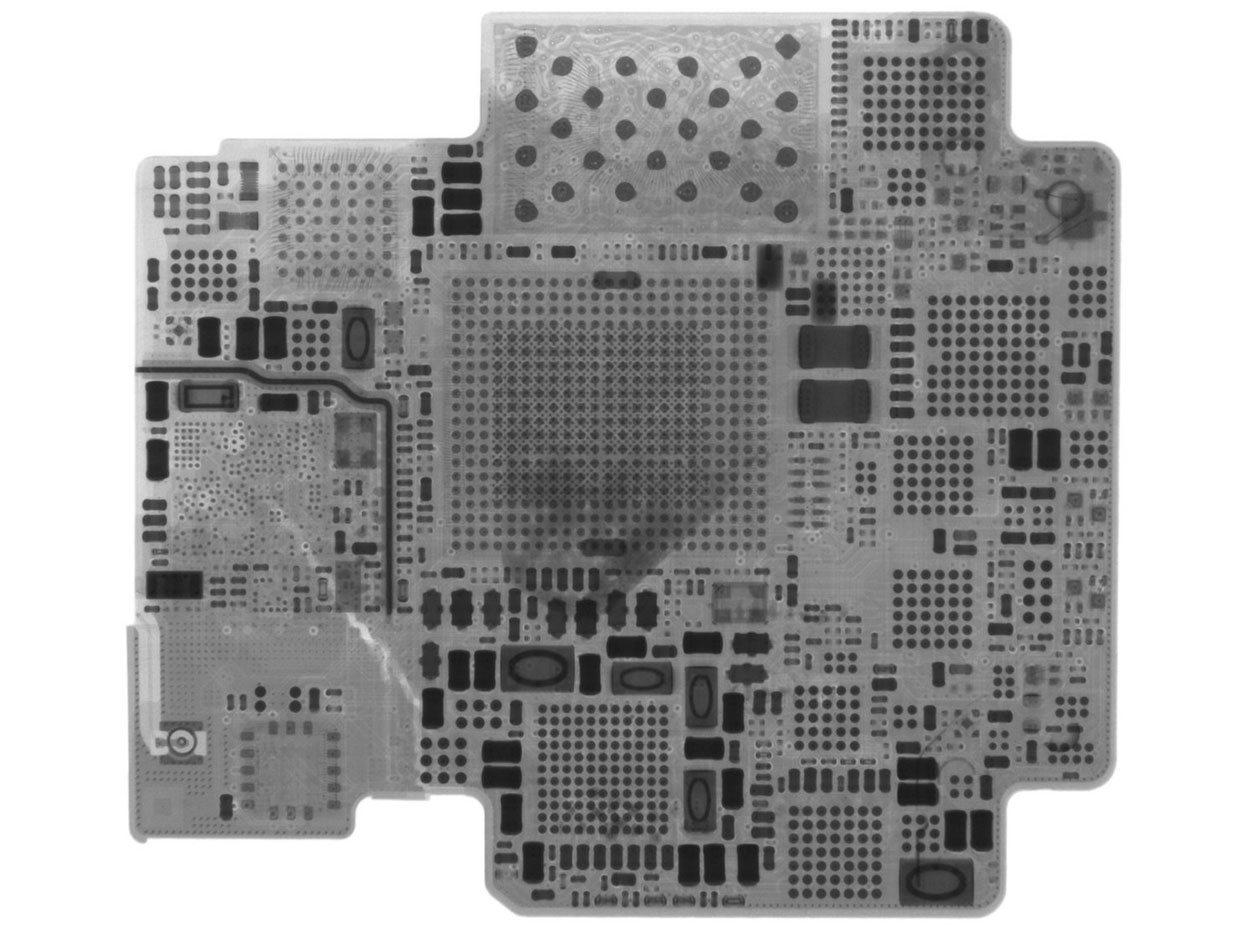

The X-ray shows a lot of tiny points of connection of wires, combining chips within S1.

Apple followed the same path when it finally entered the market in 2015, but slightly changed the scheme - and the key to this can be found in the product name itself. This is not an Apple Smartwatch or even an Apple iWatch, it's just an Apple Watch. Apple would love to enter the smartwatch market, but their main goal was a luxury watch market consisting of people who needed a device that not only showed time, but also conveyed status - and such potential buyers would be happy to fork out such a toy.

Such a strategy was unavailable to most competitors. Most companies had customers, but Apple had admirers who considered buying their products a status step. Apple has successfully become a premium brand in the luxury watch market. When these watches were first introduced, Apple even offered them a version with a solid gold case for $ 10,000 (and after three years, the button, stopped making updates for it).

But brand loyalty has limits. Even for members of the Apple cult. Continued success was to depend on the benefits of Watch. Apple has directed all its extensive engineering capabilities to create a special electronic circuit. The result is a tiny module, which the company calls the “system in package” (SiP), which contains almost all the electronics necessary for the watch. SiP are several integrated circuits and their circuits on a single board. The first Apple Watch SiP, S1, included a 32-bit ARMv7 processor at 520 MHz, DRAM (from Elpida Memory, now part of Micron Technology), NFC technology from NXP Semiconductor and AMS (formerly Austria Microsystems), 8 GB flash memory from SanDisk and Toshiba, wireless charging from Integrated Device Technology, touch technology from Analog Devices, and more.

The first Apple Watches had not the best working hours from a single charge, some owners complained about their poor performance, but the company quickly fixed it. With the exception of these first shortcomings, Apple Watch has been reliably designed, stylishly made and useful in use, just like any other smart watch. Perhaps even above average.

This utility depends on the placement of watches in the popular, carefully controlled and well-interconnected universe of Apple products and services - and this is another advantage that is difficult to repeat for a competitor. As co-founder of Apple, Steve Wozniak recently said: “I have Apple Pay on my watch, there are boarding passes, movie tickets - everything is so simple!” Woz, an enthusiast of any new technologies, regardless of their origin, recently exclaimed that Apple Watch were his favorite gadget.

Perhaps Apple is just beginning its journey in the world of wearable electronics. Apple Watch has an interesting potential to play a key role in the ecosystem of wearable gadgets, such devices as augmented reality glasses and smart cloth can enter. Apple director Tim Cook said recently that "Wearable electronics was the second largest segment in profit after the iPhone, and this is quite an impressive result for a business that opened just three years ago."

The original Matsushita / Technics SL-1200, presented in 1972, was one of the first direct-drive vinyl record players. She had a red strobe, in a prominent cylindrical body in front of and to the left of the disc. The light was used in conjunction with marks on the disk for fine adjustment of the speed of rotation.

Vinyl record player with direct drive [or in Soviet terminology, electric player / approx. trans.] became the only device to play music, turned into a musical instrument. In this capacity, turntables were the most important element of the birth of hip-hop, the most popular and long-lived of new music genres in the last 50 years. And there was one particular model that was most used in the early days of hip-hop: Technics SL-1200.

It was an unexpected twist on the long history of recorded sound. Of all his inventions, Thomas Edison liked the phonograph the most. His first car, created in 1877, kept a record on cylindrical carriers. In 1892, Emil Berlinger began selling records on disks. The incredible success of the disk format has led to the fact that he fully occupied the player market. Many of the first models spun discs at a constant speed with flywheels and cranks. To unleash the drive, some of the early machines used a drive with an idler pulley : the motor spun the idler pulley, and the latter unscrewed the disc. The next step was the drive belts (moreover, opinions were divided about whether this was a step forward or backward ).

Turntable manufacturers realized that it would be better to get rid of the drive belt, which was not well suited to maintain a constant rotational speed, and also often refused. Some tried to make direct-drive turntables, but this required a very accurate system for controlling the speed of acceleration and rotation of the motor, and for decades such possibilities went beyond the limits of practically accessible to the mass market.

But electronics finally provided these tools. The first direct-drive electronic spinner, the SP10, was developed by Shuichi Obata, an engineer from Technics, a division of Matsushita. She entered the market in 1969 (one of them is in the New York Museum of Modern Art). The SL-1200, also developed by Obata, appeared three years later and several intermediate models.

Direct-drive turntables had high torque, so they could spin almost instantly. They also coped better than others with maintaining a constant speed of rotation, which almost completely eliminated the floating of tone and the trembling of sound — audible distortions that appear due to a change in the speed of rotation. By the early 1970s, DJs on radio and in clubs, as well as recording engineers, began to use direct-drive turntables everywhere.

And it was not only the sound. Direct drive could be manipulated by hand, without fear of breaking it - and this was extremely important for DJs. On a turntable with a power belt, it is quite difficult to start playing a recording from a certain point, because such a drive can spin up to the desired speed unpredictable. If you place the needle on the track too close to the beginning of the music, you will get a distorted playback of the beginning of the recording. If you start too far, get a few seconds of silence. So in the era of power belts, DJs developed a technique called slip cue. They found the beginning of the song on the record, turned it a bit in the opposite direction, and left the needle in this place, holding the record with their hands while the disc of the player unwound. When they had to start a song, they released the record. The precise inclusion of the song by this method was the subject of professional DJ pride, when they were still playing records from the records, because the result a) sounded good, and b) if used incorrectly, the technology led to the wear of the drive mechanism.

Since the direct drive torque is much higher, for them, this technique works better. And still they can be turned back without problems - that is inadmissible to do with a belt drive. For DJs, this meant that they could easily and quickly unscrew the record back to find the right moment.

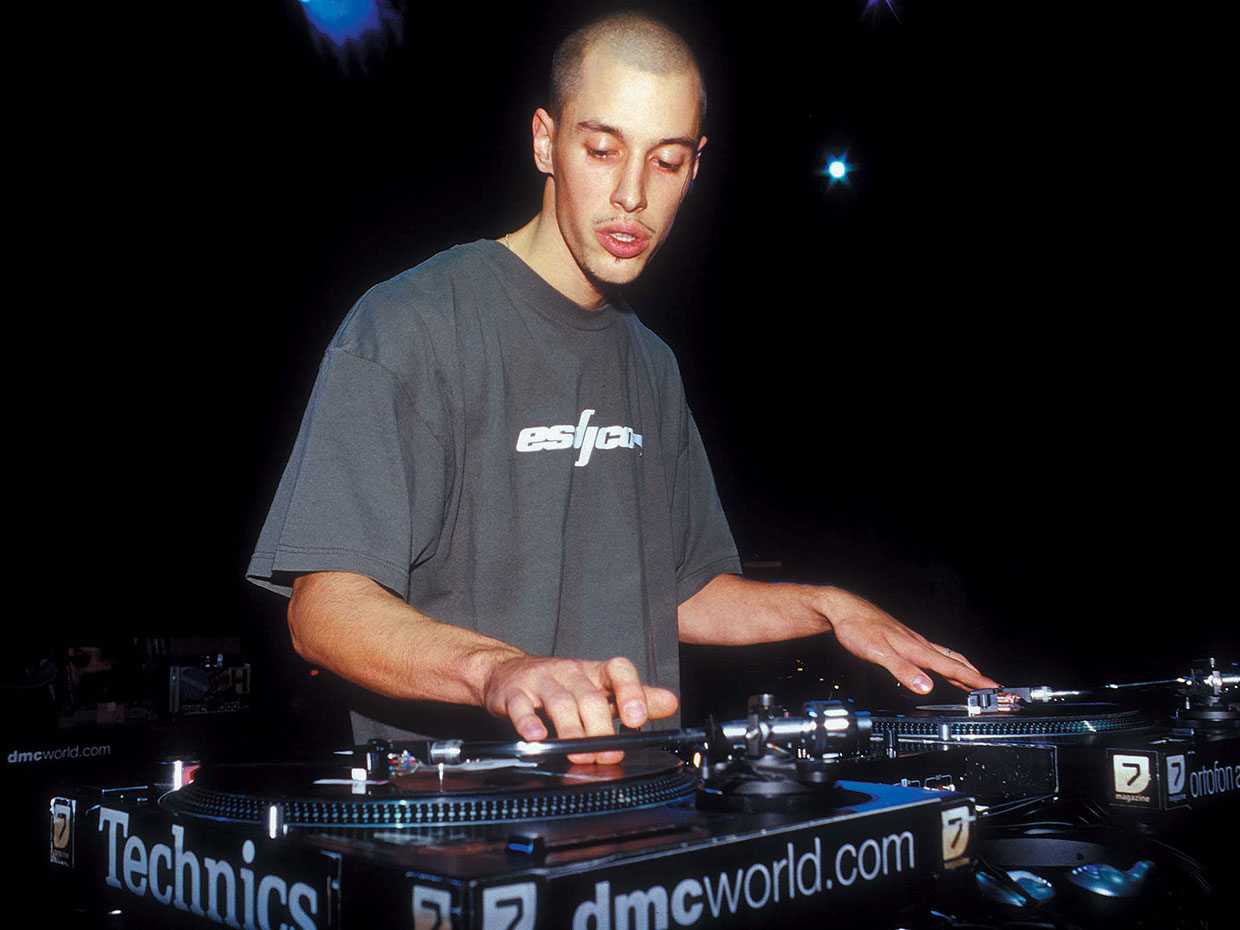

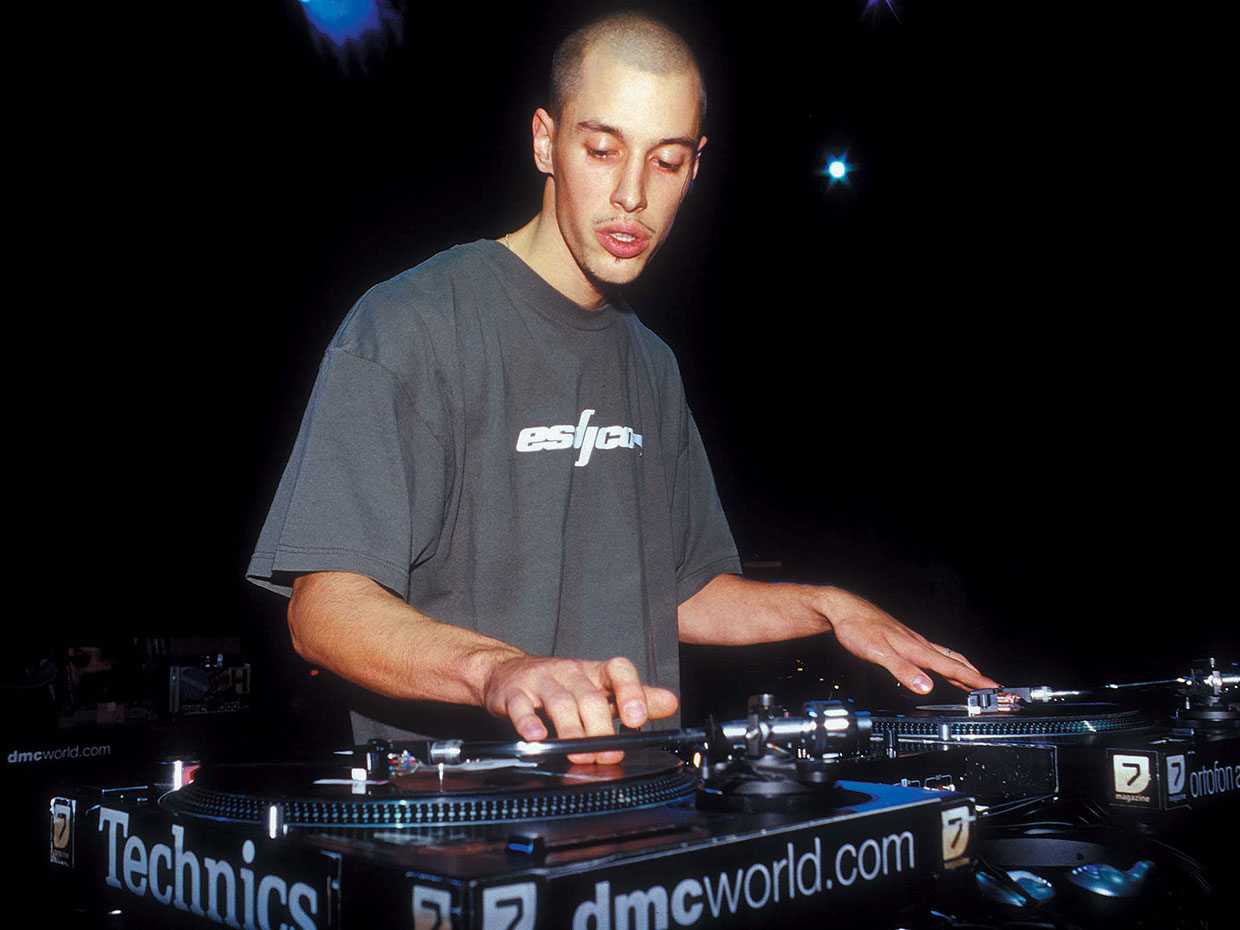

Hey Mister DJ: SL-1200 quickly became the favorite turntable of professional DJs. Pictured is Swedish DJ Jay K at the 2001 DMC World DJ Mixing Championship in London.

Regardless of whether the DJ works on the radio or in the club, he has at least two turntables. Usually they play simultaneously only during the transition between songs. But in the early 1970s, some DJs in the clubs began to experiment - they left sound from both turntables, and while one was playing the song, they turned on the other through the speakers, sometimes so quickly that the distorted sounds from one turntable coincided with the bass of the other. This scratch technique has become a hallmark of early hip hop compositions. Scratch could not be performed on the drive belts, it would have killed them.

SL-1200 . , Technics . , SL-1200 , , .

SL-1200 38 1972 . Technics , CD , , CD. 2010 . – LP. SL-1200 2016-.

Cobra 138XLR in the form in which it was sold, was one of the most successful CB radio stations available in the late 1970s, in the heyday of similar systems. But a whole galaxy of adherents of the 138XLR managed to win thanks to the excellent sound quality and the availability of after-sales modifications.

It is impossible to understand the value of CB radio stations apart from their cultural context in the period of their popularity in the USA. The 1970s were a period full of strange quirks, and CB radio was one of the most striking ones (see also: stones as pets, macrame and stringing – , ). - 1975 «» ( ), , " ", Citizens Band (1977) " " (1978) – . - , , -: 1970- .

The work of the trucker suggests loneliness, and bilateral CB stations provided the opportunity to create a community. Also at that time, truckers' salary depended on the speed of delivery of goods. This prompted drivers to drive beyond the speed limit, which in 1974 the federal government reduced to 89 km / h (55 mph). Truckers began to use radios to warn each other about where Smokey is based - patrolmen on the highway. Other drivers found out about this, and began buying radios for the same purpose.

The truckers also had to modify the existing equipment. It all started with the truck, and then spread to the radio. Among the common modifications were whip antennas and hacks such as increased power and modulation, but those who were able to sort out the inside of the radio, figured out how to add additional channels. Some people just think that more is better, but for truckers, this meant that they could add channels that were inaccessible to all sorts of idlers who thought that shouting "violator, offender" in the voice of Burt Reynolds is a shit. Also, the use of these channels complicated the work of Smokey, who bought their own radios for tracking truckers trying to exceed the speed limit.

Until 1977, adding channels on the ST-radio was expensive, and required very painstaking installation and calibration of crystals. Crystals were the traditional low-cost way to create and maintain frequency in a small radio transmitter. But at about that time, manufacturers began to change crystals in basic CB models for silicon oscillators with phase locked loop.(PLL). The PLL technology used a voltage controlled oscillator to create a base frequency, and the rest of the electronics used to compare this frequency with the one generated by one or more crystals. With a variable frequency divider between a voltage controlled oscillator and a phase detector, the frequency of radio transmission was determined by a divider. The truck drivers soon discovered that the PLL can be programmed, and that it was cheap and easy to program additional frequencies.

Cobra's secret weapon was a Uniden PLL chip. It can be seen on the left, above the green switch housing.

Cobra Uniden, 858SSB. , Uniden, uPD858. , 399 – , , , 40 , .

, 1977 Cobra 138XLR, $150, . , Uniden, . 138XLR , . - . , , .

138XLR -, 1977 - – 13 . , , ( 26,965 27,405 ). , , . , - . Cobra 1978 .

GPS Navigator Garmin StreetPilot

Garmin StreetPilot helped destroy the street atlas market, but may have retained several marriages

The way forward: Garmin StreetPilot, which appeared in 1998 at a price of $ 400, was one of the first practical and affordable GPS navigators

If you were born before 1980, then they probably expected you to learn how to work with cards in your teens. If you didn’t know how to get to a place, until you sat behind the wheel, you couldn’t get there.

')

There were exceptions. If you didn’t know how to drive where you wanted, you could stop and ask for directions. Or, if you had a passenger, you could rely on him (or her) as a navigator.

However, due to inconsistencies with these conditions, marriages sometimes collapsed. After the appearance of Garmin, this was no longer the case. As well as Garmin and its competitors almost destroyed the market of road atlases.

The path to such dramatic social change began within the walls of the US Department of Defense. In the early 1970s, the ministry began to create a global positioning system, GPS, but until 1983, it used it exclusively. That year, the government allowed it to be used for consumer purposes - albeit with a worsened resolution. In 1996, the government decided that GPS would be a dual-use technology - from a practical point of view, this meant that commercial companies would finally be able to obtain the same accurate data as the government and the military.

Various manufacturers rushed to make GPS systems for commercial navigation in the late 1980s, but due to poor resolution and high cost, their products weren’t scattered from the shelves. For example, Magellan Navigation introduced the first portable commercial system for GPS navigation, the NAV 1000, in 1989. Some customers were satisfied with these devices, mainly those who spent a lot of time in nature, but few pedestrians thought it necessary to purchase a device the size of a brick at a price of almost $ 3,000, which could tell what street they are on, and also give them their exact coordinates in degrees, minutes and seconds.

The use of navigation in cars promised the best prospects. Since the early 1990s, several automakers began offering GPS navigation systems, but then the high resolution was inaccessible, and the accuracy left much to be desired. And the high cost of GPS technology meant that these devices were available only in luxury models, which were sold a little.

By 1998, the cost of GPS had dropped significantly, and Garmin’s chance to earn was no worse than that of others. It was founded in 1989 under the name ProNav, and had experience creating GPS navigators for the military. Garmin was able to make a portable model at an attractive price (about $ 400), on which it was possible to download accurate street maps.

The company's first consumer product, StreetPilot, measured about 17x8x5.5 cm and weighed about 500 grams, including six AA batteries. It had a black and white LED screen of 240x160 pixels (the following year, Garmin released a model with a color screen).

The model had a 12-channel GPS receiver, and it provided positioning accuracy of no worse than 15 meters, with a maximum accuracy of 1-5 meters with differentiated GPS, when satellite signals complement signals from ground stations.

Included with StreetPilot were maps where highways between the states and within the states of the USA, rivers and lakes of the USA, Canada and Mexico, and the main streets of the main settlements were reflected. Users could buy compact discs with maps of different cities, where streets and useful establishments, such as gas stations and public catering facilities, were presented and download this data to memory cartridges (8 and 16 MB) connected to the device. Users could enter a destination address, and StreetPilot guided them in the shortest possible way. In general, StreetPilot offered the simplest version of the navigator, without information about traffic jams, and without all that can be obtained today in the free application for a smartphone. But at the time, this was a revelation.

The subsequent model, the StreetPilot III of 2002, could boast a color display with a diagonal of 3.85 ", a resolution of 305x160 and voice queries.

Garmin and its followers not only changed the way people travel by car, but also came close to devaluing for most people the ability to understand cards. And in the process, perhaps, saved several marriages.

Sony trinitron

Sony Trinitron not only elevated Sony to the rank of paramount technological innovators, but also made Japan a first-class source of advanced electronics.

The funnel: The original Sony Trinitron KV-1310 was introduced in Japan at a press conference on April 15, 1968.

Trinitron, unveiled by Sony in 1968, was the first significant technological breakthrough in the field of color television since such televisions first appeared on the market in the early 1950s. And, like many innovations, it was the result of the evolution of several failed projects.

The TV showed a color image when phosphor points were excited on the inside of the screen. Among the main elements of the first color TV were, if you count from the back to the front: three electronic emitters, or "guns", set by a triangle; they pointed to a barrier, a shadow mask in which holes were drilled; after that there was a screen with phosphorus.

The screen was littered with millions of tiny phosphorescent points, collected by three. When the electrons hit the dots, they emit light. In each triad there were three points, chemically created in such a way that one of them radiated red, one green, and one blue. In theory, any light visible to the human eye can be created from different combinations of red, green, and blue (red, green, blue - RGB).

Each of the three electron guns aimed only at one phosphor point in each RGB triplet. The color produced by each triplet could be chosen by highlighting the desired combination of dots with the cannons to create the desired color. The electrons from the guns ran around the screen to and fro many times a second, highlighting the necessary points and creating color images on the screen. In order to receive moving images, the screen needed to be turned on, or “painted”, many times per second. This “refresh rate” was usually at least 60 frames per second.

However, there was one problem. It was possible to aim each gun at only one point in each triplet if the guns emitted electrons by a narrow beam. But this did not happen - the “ray” of electrons looked more like splashes.

Manufacturers struggled with this with the help of a shadow mask. Holes in it passed only those electrons from each gun, which were supposed to reach the desired point in each triad. All other electrons were blocked.

Such a scheme worked, for the most part. The guns had to be perfectly aligned, and they were knocked down often enough so that they had to be periodically repaired by a professional. Moreover, shadow masks blocked a multitude of electrons that would otherwise cause the RGB triads to be phosphoressed brighter. The color screens of the televisions were not as bright as they could be, in part because of the waste of all these charged particles.

It was possible to approach improvement of quality of TVs from the different parties. For example, RCA, the world leader in the manufacture of television sets at the time, began to use rare-earth elements, which were more clearly phosphorescent. General Electric changed the location of the guns, putting them in a row (instead of a triangle) and achieved good results. A tiny band in the United States, Chromatic Television Laboratories , followed a different path. They based their approach on the idea of the famous physicist Ernest Orlando Lawrence of the University of California at Berkeley, trying to use one electronic gun, and replacing the shadow mask with a grid of charged vertical wires. This technology, called the chromatron [Chromatron], also gave a brighter picture due to the lack of a shadow mask, although Chromatic never managed to get its system to work reliably.

Sony intended not to copy other people's ideas (and not to deduct royalties). At a trade fair in 1961, funded by the Institute of Radio Engineers, one of the communities that preceded IEEE, Sony ’s directors saw a working Chromatic television. They almost on the spot agreed on a license. Sony created the TV based technology and brought it to market in 1965.

Sony's chromatrons gave an excellent color picture, but they could not be reliably produced in massive quantities, and their cost was so much more profitable from them that this business threatened to sink Sony, says Susumi Yoshida, an engineer who worked on Chromatron and Trinitron technologies. The company needed to come up with another way to produce color TVs.

Trinity Trinitron: three of the four key figures of the Trinitron project are depicted in the photo to the left; these are Susumi Yoshida, Akio Ogoshi and Senri Miyoka, who are present at the technology presentation in April 1968. One of the founders of Sony, Masaru Ibuka (right) was also an engineer, then became president of the company, and personally supervised the work of the Trinitron team.

Four leading engineers of the Trinitron Susumi Yoshida, Akio Ogoshi and Senri Miyaoka and Masaru Ibuka project. Yoshida claims that the revolutionary idea of trinitron came to him. He liked GE's approach to electronic emitters, where a linear system was used instead of a triangular one, since it was easier to reduce the rays into one point. However, he liked the idea with a single gun (as in the Zromatron), since it was cheaper. Yoshida wondered if it was impossible to place the three cathodes in one line inside one gun?

In short, it turned out that this can be done. Additional adjustments were needed, including the installation of reflective plates above the gun, which helped focus the electron beams, and create a chemical etching process to create an aperture grid that performed the same task as the grid of charged chromatron wires, and in much the same way. But the system worked, it could be mass produced at an affordable price, it was stable, it almost did not need to be professionally set up after the sale. And, more importantly, she gave a beautiful color image.

True colors: The first Trinitron KV-1210U hit the US in 1969, and its recommended price was $ 319.95, which is about $ 2,200 in 2019 prices.

Appearing in 1968, Trinitron immediately became a hit. Improved picture quality justified the high cost. In 1973, he became the first consumer electronics device to receive an Emmy Award. Sony eventually sold 280 million copies of Trinitron, first as a TV, and then as computer monitors.

And if Trinitron were just a huge step in television technology and deafening commercial success, it would have earned him a place in the Hall of Fame. But these were not his only merits. He has made Sony a first-class source of technological innovations. Its sales have helped pay for the successful period of Sony, with which for so many innovations in such a wide range of consumer products and for such a long period of several decades very few people can match. Moreover, the success of Sony was the success of Japan. Before Trinitron, most of the electronics in the country were cheap and unreliable. Trinitron has become one of the products that made Japan the source of world-class advanced electronics.

Apple Watch

The $ 10,000 Apple Watch Gold has become an extremely vivid reflection of the company's ability to request premium prices; it is a pity that the company, after three years, has ceased to issue updates for them

Just in time: May 9, 2015, journalists were given the opportunity to experience the Apple Watch before their official release next month. In the second fiscal quarter of the year, 4.2 million watches will be sold, making them the most popular wearable device.

Apple Watch can not be called the first smart watch. One can argue about whether this is the best smart watch. But this is, without a doubt, the best smart watches for sales - by November 2018, they already sold 33 million. And given their market share, they will continue to be the best-selling gadget of this type. Apple Watch has become one of the finest examples of how a company entered the right market with the right product at the right time. It was a great example of a timely (um) exit.

People have come up with smart watches many years ago. Comic hero Dick Tracy donned such a watch in 1946. In 1984, Seiko Epson introduced a clock synchronized with a PC. In the 90s, Timex, IBM and Samsung attempted to release an electronic watch, but they were let down by the imperfection of technology. In the 2000s, communication with the clock remained unreliable, the application was inconvenient. In 2004, Microsoft introduced the Spot smart watch; they relied on a proprietary wireless network protocol that worked on the FM frequency. It was followed by Motorola, Sony Ericsson, Vyzin Electronics and others.

In the same decade, Fitbit and other companies became pioneers in the market of fitness trackers that track carrier movement, heartbeat, sleep, and other parameters related to sleep. The next logical step seemed to be a combination of a fitness tracker and a smart watch, but fans of fitness trackers rejected the combined devices for several years after that.

Launched from kickstart: the crowdfunding phenomenon Pebble Smart Watch became an important pioneer in this whole story, but did not survive after the appearance of such a monster as Apple Watch

In 2012, Pebble Technology Corp. introduced the first successful smart watch, Pebble. They were followed by Omate TrueSmart in 2013, followed by LG, Razer, Samsung, Sony and some others. Some of the devices were combined, and for some reason people started to get used to them.

The difficulty facing each manufacturer of smart watches was that they tried to sell watches to a generation that had lost the habit of wearing them because they were used to checking with the watches on the phone.

Most manufacturers went the obvious way - made a watch that served as a supplement to the phones. It was possible to look at the clock to check the latest messages, mail or alarm clocks, without pulling the phone out of your pocket or purse.

At the core of Apple: everything important in the Apple Watch was contained on the S1 module. The wrong shape in its center is the processor heatsink.

The X-ray shows a lot of tiny points of connection of wires, combining chips within S1.

Apple followed the same path when it finally entered the market in 2015, but slightly changed the scheme - and the key to this can be found in the product name itself. This is not an Apple Smartwatch or even an Apple iWatch, it's just an Apple Watch. Apple would love to enter the smartwatch market, but their main goal was a luxury watch market consisting of people who needed a device that not only showed time, but also conveyed status - and such potential buyers would be happy to fork out such a toy.

Such a strategy was unavailable to most competitors. Most companies had customers, but Apple had admirers who considered buying their products a status step. Apple has successfully become a premium brand in the luxury watch market. When these watches were first introduced, Apple even offered them a version with a solid gold case for $ 10,000 (and after three years, the button, stopped making updates for it).

But brand loyalty has limits. Even for members of the Apple cult. Continued success was to depend on the benefits of Watch. Apple has directed all its extensive engineering capabilities to create a special electronic circuit. The result is a tiny module, which the company calls the “system in package” (SiP), which contains almost all the electronics necessary for the watch. SiP are several integrated circuits and their circuits on a single board. The first Apple Watch SiP, S1, included a 32-bit ARMv7 processor at 520 MHz, DRAM (from Elpida Memory, now part of Micron Technology), NFC technology from NXP Semiconductor and AMS (formerly Austria Microsystems), 8 GB flash memory from SanDisk and Toshiba, wireless charging from Integrated Device Technology, touch technology from Analog Devices, and more.

The first Apple Watches had not the best working hours from a single charge, some owners complained about their poor performance, but the company quickly fixed it. With the exception of these first shortcomings, Apple Watch has been reliably designed, stylishly made and useful in use, just like any other smart watch. Perhaps even above average.

This utility depends on the placement of watches in the popular, carefully controlled and well-interconnected universe of Apple products and services - and this is another advantage that is difficult to repeat for a competitor. As co-founder of Apple, Steve Wozniak recently said: “I have Apple Pay on my watch, there are boarding passes, movie tickets - everything is so simple!” Woz, an enthusiast of any new technologies, regardless of their origin, recently exclaimed that Apple Watch were his favorite gadget.

Perhaps Apple is just beginning its journey in the world of wearable electronics. Apple Watch has an interesting potential to play a key role in the ecosystem of wearable gadgets, such devices as augmented reality glasses and smart cloth can enter. Apple director Tim Cook said recently that "Wearable electronics was the second largest segment in profit after the iPhone, and this is quite an impressive result for a business that opened just three years ago."

The Matsushita / Technics SL-1200

Technics SL-1200, one of the first direct-drive turntables, distinguished itself by becoming a device for listening to music, which was also used for musical performance.

The original Matsushita / Technics SL-1200, presented in 1972, was one of the first direct-drive vinyl record players. She had a red strobe, in a prominent cylindrical body in front of and to the left of the disc. The light was used in conjunction with marks on the disk for fine adjustment of the speed of rotation.

Vinyl record player with direct drive [or in Soviet terminology, electric player / approx. trans.] became the only device to play music, turned into a musical instrument. In this capacity, turntables were the most important element of the birth of hip-hop, the most popular and long-lived of new music genres in the last 50 years. And there was one particular model that was most used in the early days of hip-hop: Technics SL-1200.

It was an unexpected twist on the long history of recorded sound. Of all his inventions, Thomas Edison liked the phonograph the most. His first car, created in 1877, kept a record on cylindrical carriers. In 1892, Emil Berlinger began selling records on disks. The incredible success of the disk format has led to the fact that he fully occupied the player market. Many of the first models spun discs at a constant speed with flywheels and cranks. To unleash the drive, some of the early machines used a drive with an idler pulley : the motor spun the idler pulley, and the latter unscrewed the disc. The next step was the drive belts (moreover, opinions were divided about whether this was a step forward or backward ).

Turntable manufacturers realized that it would be better to get rid of the drive belt, which was not well suited to maintain a constant rotational speed, and also often refused. Some tried to make direct-drive turntables, but this required a very accurate system for controlling the speed of acceleration and rotation of the motor, and for decades such possibilities went beyond the limits of practically accessible to the mass market.

But electronics finally provided these tools. The first direct-drive electronic spinner, the SP10, was developed by Shuichi Obata, an engineer from Technics, a division of Matsushita. She entered the market in 1969 (one of them is in the New York Museum of Modern Art). The SL-1200, also developed by Obata, appeared three years later and several intermediate models.

Direct-drive turntables had high torque, so they could spin almost instantly. They also coped better than others with maintaining a constant speed of rotation, which almost completely eliminated the floating of tone and the trembling of sound — audible distortions that appear due to a change in the speed of rotation. By the early 1970s, DJs on radio and in clubs, as well as recording engineers, began to use direct-drive turntables everywhere.

And it was not only the sound. Direct drive could be manipulated by hand, without fear of breaking it - and this was extremely important for DJs. On a turntable with a power belt, it is quite difficult to start playing a recording from a certain point, because such a drive can spin up to the desired speed unpredictable. If you place the needle on the track too close to the beginning of the music, you will get a distorted playback of the beginning of the recording. If you start too far, get a few seconds of silence. So in the era of power belts, DJs developed a technique called slip cue. They found the beginning of the song on the record, turned it a bit in the opposite direction, and left the needle in this place, holding the record with their hands while the disc of the player unwound. When they had to start a song, they released the record. The precise inclusion of the song by this method was the subject of professional DJ pride, when they were still playing records from the records, because the result a) sounded good, and b) if used incorrectly, the technology led to the wear of the drive mechanism.

Since the direct drive torque is much higher, for them, this technique works better. And still they can be turned back without problems - that is inadmissible to do with a belt drive. For DJs, this meant that they could easily and quickly unscrew the record back to find the right moment.

Hey Mister DJ: SL-1200 quickly became the favorite turntable of professional DJs. Pictured is Swedish DJ Jay K at the 2001 DMC World DJ Mixing Championship in London.

Regardless of whether the DJ works on the radio or in the club, he has at least two turntables. Usually they play simultaneously only during the transition between songs. But in the early 1970s, some DJs in the clubs began to experiment - they left sound from both turntables, and while one was playing the song, they turned on the other through the speakers, sometimes so quickly that the distorted sounds from one turntable coincided with the bass of the other. This scratch technique has become a hallmark of early hip hop compositions. Scratch could not be performed on the drive belts, it would have killed them.

SL-1200 . , Technics . , SL-1200 , , .

SL-1200 38 1972 . Technics , CD , , CD. 2010 . – LP. SL-1200 2016-.

Cobra 138XLR CB-

The Cobra 138XLR was the most legendary CBC radio station during the brief but beautiful golden age of civilian radio stations.

Cobra 138XLR in the form in which it was sold, was one of the most successful CB radio stations available in the late 1970s, in the heyday of similar systems. But a whole galaxy of adherents of the 138XLR managed to win thanks to the excellent sound quality and the availability of after-sales modifications.

It is impossible to understand the value of CB radio stations apart from their cultural context in the period of their popularity in the USA. The 1970s were a period full of strange quirks, and CB radio was one of the most striking ones (see also: stones as pets, macrame and stringing – , ). - 1975 «» ( ), , " ", Citizens Band (1977) " " (1978) – . - , , -: 1970- .

The work of the trucker suggests loneliness, and bilateral CB stations provided the opportunity to create a community. Also at that time, truckers' salary depended on the speed of delivery of goods. This prompted drivers to drive beyond the speed limit, which in 1974 the federal government reduced to 89 km / h (55 mph). Truckers began to use radios to warn each other about where Smokey is based - patrolmen on the highway. Other drivers found out about this, and began buying radios for the same purpose.

The truckers also had to modify the existing equipment. It all started with the truck, and then spread to the radio. Among the common modifications were whip antennas and hacks such as increased power and modulation, but those who were able to sort out the inside of the radio, figured out how to add additional channels. Some people just think that more is better, but for truckers, this meant that they could add channels that were inaccessible to all sorts of idlers who thought that shouting "violator, offender" in the voice of Burt Reynolds is a shit. Also, the use of these channels complicated the work of Smokey, who bought their own radios for tracking truckers trying to exceed the speed limit.

Until 1977, adding channels on the ST-radio was expensive, and required very painstaking installation and calibration of crystals. Crystals were the traditional low-cost way to create and maintain frequency in a small radio transmitter. But at about that time, manufacturers began to change crystals in basic CB models for silicon oscillators with phase locked loop.(PLL). The PLL technology used a voltage controlled oscillator to create a base frequency, and the rest of the electronics used to compare this frequency with the one generated by one or more crystals. With a variable frequency divider between a voltage controlled oscillator and a phase detector, the frequency of radio transmission was determined by a divider. The truck drivers soon discovered that the PLL can be programmed, and that it was cheap and easy to program additional frequencies.

Cobra's secret weapon was a Uniden PLL chip. It can be seen on the left, above the green switch housing.

Cobra Uniden, 858SSB. , Uniden, uPD858. , 399 – , , , 40 , .

, 1977 Cobra 138XLR, $150, . , Uniden, . 138XLR , . - . , , .

138XLR -, 1977 - – 13 . , , ( 26,965 27,405 ). , , . , - . Cobra 1978 .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/435296/

All Articles