Jessica Livingston: “How we created the Y Combinator. Emotional component "

“We were to judge applicants not by who they were, but by who they could be.”

In 2005, I had a hand in the base of Y Combinator, the first “accelerator”. Today there are hundreds of them around the world, but in 2005 what we did was so unusual that most people in Silicon Valley considered us insignificant.

Y Combinator started the same way as most other startups: with the assumption that people need our product. In the end, it turned out that they really needed it, and we grew and grew. To date, we have financed 1,867 startups totaling more than $ 100 billion.

')

So, since I fell through a type of startup that many of you are hoping for, I want to tell you my own story.

If you only heard about me through the media, you might get the impression that my contribution to the Y Combinator is that I am Paul Graham's wife. And although I like being his wife, yet I made a slightly more significant contribution.

The translation was made with the support of the company EDISON Software , which invests in promising start-ups , as well as develops various cloud services .I was born in Minneapolis in 1971. Later that year, my mother left home, leaving her father alone with a small child. So he took me back to Boston, where my grandmother lived. I lived with her from Monday to Friday while my father worked, and then spent the weekend with him.

My grandmother was my main role model. She was a very independent person. All who knew her, characterized her with the same phrase: "free-thinking". For example, in the winter, after she put me to bed, she went out and worked until late at night on the giant ice sculptures that she built in the yard.

She did what she wanted, and she didn’t care if she was considered out of this world.

Despite the fact that I grew up without a mother, my childhood was quite happy. My father sacrificed a lot so that I could get a good education, and he constantly supported me.

When I was little, I played football, and in the 9th grade, we participated in an away game against a school called Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. The place seemed incredibly fabulous to me, and I immediately decided that I would go there to school.

Then I did not suspect that this decision would have contradictory consequences. In my old school I was, so to speak, a big fish in a small pond. I was an excellent student and I was easily given sports. But when I moved to Andover in the fall of 1986, it turned out that everyone there was an excellent student and they were easily given sports. I was very upset and, in fact, lowered my hands.

I became a mediocre student and didn’t do anything spectacular or remarkable over the next decade. This time can be called my own Dark Ages.

It is a little awkward to remember them, but I think it will be important to mention this. When journalists and biographers write about the founders of successful projects, they often pay attention to the fact that even in their youth they were promised success. In my case, there were definitely no such predictions. No one would call me the person who “most likely will succeed in life” in life.

But although I didn’t have any “achievements”, in my youth I still had three main features that allowed the Y Combinator project to become a reality.

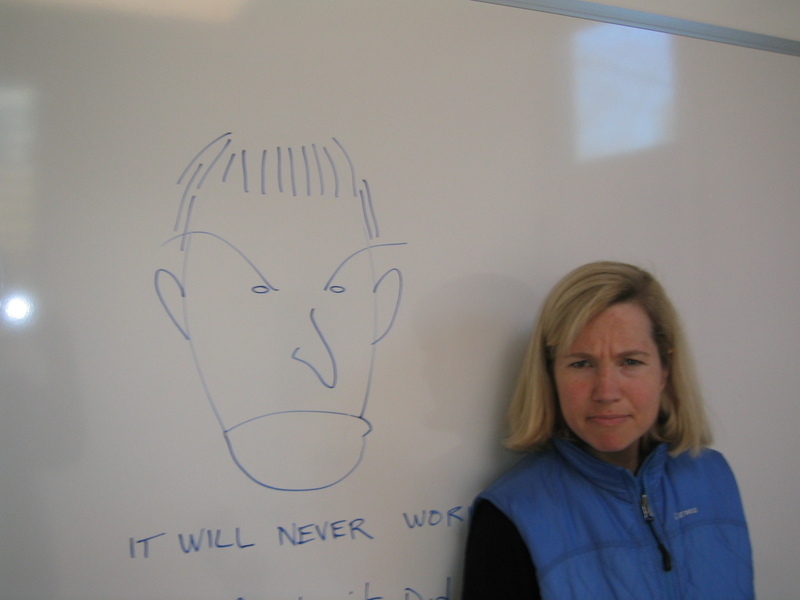

The first was the quality that made my co-founders YC nickname me "Social Radar". I was the child who cannot just pass by. If something seemed strange or unusual, I noticed and researched it. I have always tried to understand things, relying on my gut subtle social signals.

Secondly, I never liked to be subordinate to someone. I hated anyone who told me what to do or not do: parents, teachers, bosses, people with whom I was forced to cooperate, but did not agree with them - in short, everyone.

And the third distinguishing feature in me was that I was always an open, direct, honest person. My grandmother and my father were both like that.

But I will come back to this point later.

The day after I graduated from college, my beloved grandmother died of cancer. It was a very sad and lonely time of my life. And now it was assumed that I should find a job with a diploma in the English language and absolutely no idea what I would like to do.

I found a job at Fidelity Investments in their customer service group, answering calls from 3:30 to midnight every day. In fact, it all came down to talking to retail investors about why their Magellan account closed that day. Nightmare. I did not like this work, but I liked the fact that I generally have it. I worked hard, got paid for it, and my homework did not hang over my head. That was great. After Fidelity, I worked in the investor relations department in New York, then in Food & Wine magazine and in a car consulting firm. I even worked briefly as a wedding planner.

In 2003, I worked in the marketing department at an investment bank in Boston, and then I first met Paul Graham at a party at his house.

We started dating, and I felt that I finally met Mr. Togo myself.

Despite the fact that we had a completely different past, we were remarkably similar. If I thought it impossible that I would ever want to obey someone, then Paul approached the possibility of this being the closest.

He returned to Cambridge after he sold his startup Viaweb Yahoo, and at that time wrote essays, worked on programming languages, published a book and treated his exhausting fear of flying, learning to fly a hang glider.

Paul solves problems like no one else. In addition, he is a genius in terms of expanding ideas and radically improving things. One of his defining features as if telling people: "You know what you have to do ..."

Paul and his circle of friends introduced me to this new world of startups. It seemed far more exciting than the late stage of the information technology companies that I sold at the investment bank. I read the Startup book by Jerry Kaplan about his company called GO, which deals with pen-based interfaces, and I immediately sold myself with giblets. It was like a light shining from heaven.

I wanted to hear more stories about the early days of startups, so I started working on a book containing interviews with the founders of startups. The book was called “Founders at Work” and was published in 2007.

The more I was interested in startups, the less I was interested in my work. The Bubble burst a few years ago and the investment bank sharply reduced its expenses. It was boring and unpleasant to work there.

So I applied for a marketing job at a venture capital firm, where I felt I could be a step closer to the more exciting world of startups. While I was doing what I interviewed and worked at a venture capital firm, Paul every evening at dinner explained to me that “I know what I have to do,” telling me how I can change the venture business, if I just do it. We spent hours talking about how difficult it was to find funding for start-ups in the early stages, and most importantly, how much the number of people who would be able to launch a start-up if it would be easier.

As the venture capital firm began to work more and more with me, Paul's ideas seemed more convincing to me, until one night Paul said, "Let's just do it ourselves." The next day, we convinced co-founders Paul from Viaweb, Robert and Trevor to join us part-time.

The initial plan was for them to select and advise start-ups, and I did the rest.

Instead of giving large sums to a small number of well-known startups, as traditional venture capital firms did, we gave small sums to a large number of startups in the early stages, and then gave them a lot of help.

Our initial target audience was programmers who, we believed, could cope with the technical aspects of a startup, but knew nothing about everything else, like Paul, Robert and Trevor once.

In addition, we believed in young project founders, unlike most investors at the time. It was at a time when Google Venture Capitalists insisted that the founders of a startup hire an external executive director as a condition of their A-round series.

None of us had the experience of a private venture investor providing financial and expert support to companies in the early stages of development, and this is where the idea of financing start-ups by parties came from. We decided to finance several startups in the summer in order to figure out how to be investors. In March 2005, we launched the Y Combinator website, inviting people to submit an application for what we called the “Summer Program for Startup Founders”.

That summer, we financed 8 startups and almost immediately felt the full potential of complex investment. It was much more convenient for startups. Now there were colleagues with them who were ready to help in this previously lonely process. However, for us it was also a much more efficient way to help start-ups, because we could do everything for them at once. Every Tuesday, Paul prepared dinner for all founders, and at each dinner we invited some speaker who taught them the art of a startup.

Paul spoke with all startups about what they were doing, and I helped them all register as tax subjects who pay dividends to owners of corporate rights out of net profit, while not being the tax agent of their owners, who pay taxes on their own income. In those days it was a difficult task, because in order to become a similar subject, you had to pay a lawyer $ 15,000, and then he did it for you.

The first summer we gave startups $ 6 thousand per founder, which was based on the scholarships that MIT gave out to students for the summer. At the end of the summer, we held the first Demonstration Day for an audience of about 15 investors. Reddit was in this first group, as well as the founders of Twitch, although they were working on another idea, and a geolocation startup Sam Altman.

Although we tried to finance a batch of startups, just to learn to be investors, after a couple of weeks we realized that we were moving towards something promising.

Therefore, we decided to make all our investments in batches. We also decided that we would finance the next batch of startups in Silicon Valley. We knew that many would copy us, and did not want anyone else to be "Y Combinator of Silicon Valley". We wanted to be called so ourselves.

Despite the fact that we have grown and expanded significantly in many ways, the main YC program is remarkably similar to the one that existed 13 years ago.

The question that I constantly heard from people over the years was: “What is your role in YC?” I used to be really annoyed because no one ever asked this question to Paul, Robert or Trevor. But now I think this is an interesting question.

What was the role of the sole non-technical founder of Y Combinator?

In the beginning there were tons of errands, as in any startup that just needed to be completed, and there was no one else to do them. Paul and I shared the responsibilities perfectly, which, in my opinion, is very important when you start a startup with your partner or spouse.

He made our website and application form, and I prepared other materials for this first summer: I worked with lawyers to create the Y Combinator organization and all kinds of sample legal documents for our standard investments, as well as anything that founders might need to organize your company and distribute shares correctly (quite a large number of cases, as you know, if you have ever done this!).

I also had to quickly learn how to explain to our wards how to fill out all the documents so that they would not have to pay for the services of a lawyer. I had to build a small office building in Cambridge, owned by Paul, so that we could have a weekly dinner party for 25 people. I dealt with our bank account and contacted the people with whom we need to talk at the next dinner each week.

I bought products from which Paul cooked something for dinner. I even brought the air conditioners to the founders, which I bought at Home Depot. I was the only one of us who was organized enough to put all this into practice qualitatively.

When it came to investing, I had something that my colleagues did not have: I was a social radar. I could not judge the technical capabilities of our applicants or even the majority of ideas. My co-founders were experts in these things. I looked at the quality of applicants that my colleagues did not see. Did they seem serious? Were they determined? Did they think flexibly? And most importantly, what was the relationship between the co-founders of the project? While my partners were discussing ideas with their authors, I usually silently watched them. After that, colleagues turned to me and asked: “Should we finance them?”

From the very beginning, I strictly observed that we only finance serious people. At that time, I never imagined that the people we had funded would become a community of thousands of YC graduates, but I always tried to create a community without idiots. If I understood that one of the applicants was a vain idiot, we refused to finance them. I am sure that since then we have still financed several such individuals, but in the early years I was quite strict in this matter. And I’m sure that this is the foundation of our alumni community.

So far, all this may sound a little different from what is expected from a successful investor. But when you get to the extreme in something, everything becomes diametrically opposite. Y Combinator was a new extreme in the venture business, so what made someone a good investor was something else then. Venture financing relied on growth figures and market size estimates, but that was unimportant at the stage at which we invested. What venture financing really needed were good technical experts who would see the potential of the idea, and someone like me, to understand the nature of the startupers and the relationship between them. And in order to be able to do this, we need abilities that previously no one considered important for an investor.

It was also doubly difficult, because some of the applicants were very young. We were to judge applicants not by who they were, but by who they could be. Imagine Mark Zuckerberg returning to his dorm room in 2004 with a website that allows college students to see what other students are doing at their school. It doesn't look so super impressive for traditional investors.

Another secret weapon of mine that was strangely useful for the Y Combinator project was that I was a very experienced event organizer.

Events are an important part of what YC does. When you finance startups in lots, everything becomes an event. The interview is an event, every dinner is an event, Demonstration Day is an event. As the alumni community grew, we started holding events for them, and, starting from the very first year, we held major events, such as Startup School. I have been holding events for years working in marketing, so I could organize them with one hand.

Probably the most distinguishing feature of YC from a typical investment firm is that it felt like a family. And I was his mother; I was soft and sensitive when investors were most often violent and aggressive (and I would add “ruthless” for some of them). I cared about how the applicants felt, whether they were overloaded with things, whether they were eating right. I gave them advice on relationships that were tense due to the pressure of a startup. I could listen to them for a long time and helped them with the differences and partings of the co-founders.

Starting a startup emotionally drains the founders, especially at the beginning. Sometimes they just needed someone to listen to them. Fortunately, my college career taught me to be a good listener when people talk about their relationship problems with other people.

And I always tried to be the same honest, direct and open person when I gave advice. In fact, we were all like that. Paul is the most honest person I know, so his advice is so valuable. He does not bury this quality in euphemisms or not (worse yet) refuses the truth in order not to hurt people's feelings. And no matter how straightforward his advice was then, start-ups always thanked him for being frank.

Another trait we shared with Paul was that we didn't do it for the money. We were interested in startups, we wanted to help as many people as possible get them started. This was the basis of everything we did at YC. This was what allowed us to create something so strange.

Since YC did not have any LPs (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limited_partnership) (limited partnership) in its early stages, we were not even limited to any indefinite liability of trust in front of anyone. This allowed us to take more risks in which start-ups we would choose to finance, and also allowed us to treat unsuccessful startups favorably.

This often led us to conflict with other investors who had other priorities. Initially, we had the opportunity to finance the team of the husband and wife who had a child. They worked a lot on a startup, but he clearly did not succeed. One of their investors tried to persuade one large company in the Valley to acquire them, but she eventually refused.

Paul spoke with the founders and found out that they just wanted to ensure job security so they could take a break from the constant stress of the startup. . . , , . , - (, ), , . , , .

. «». , Y Combinator .

Y Combinator , . . , YC. , , , . , . , , , , , . , , . ? ? . YC , .

. , . , , , . , , , . - .

, , , . ? , , , .

, , . , YC, . , , . , . , , .

? 9 :

- . , , , .

- , , . , , .

- , — , - . , . ( !)

- , , . , - YC. , , .

- , , . . 2005 .

- . - , .

- , . , . YC - , .

- , . , , . , . , , .

- . , — , , , .

— . , . . , : . , , . , , , , , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/435252/

All Articles