How Google tried to conquer China - and lost

There was a time when Google wanted to enter the Chinese market, and China needed Google. Now this time has passed.

Google’s first foray into Chinese markets was a short-lived experiment. Google China search system launched in 2006, and four years later it suddenly shut down for mainland China after a major hacking and disputes over censorship of search results. But in August 2018 investigative journalism website The Intercept reported that the company is secretly working on a prototype of a new censored search engine for China under the name of Project Dragonfly.

Google’s first foray into Chinese markets was a short-lived experiment. Google China search system launched in 2006, and four years later it suddenly shut down for mainland China after a major hacking and disputes over censorship of search results. But in August 2018 investigative journalism website The Intercept reported that the company is secretly working on a prototype of a new censored search engine for China under the name of Project Dragonfly.

Against the backdrop of protest by human rights defenders and some Google employees, Vice President Mike Pence called on the company to stop working on Dragonfly. He said that the system "will increase the censorship of the Communist Party and endanger the confidentiality of users." In mid-December, The Intercept reported that Google had suspended the development of Dragonfly after claims of its own privacy department, which had learned about the project from the media.

')

Some observers say that the decision to return to the world's largest market depends from Google: if it will compromise with his principles and expose censored search as China wants? But observers overlook the most important thing: this time the decision will be made by the Chinese government.

Google and China have suffered in a strange waltz for more than ten years, constantly fighting for who leads and who follows. The history of this dance demonstrates the main changes in China’s relationship with Google and the entire Silicon Valley. To understand whether China will allow Google to return to the market, we need to understand how Google and China were in such a situation, what incentives faced by each party - and how artificial intelligence can make them both dance to a new tune.

When the www.google.cn opened in 2006, the company just turned two years old. The iPhone did not yet exist, like Android smartphones, and the Chinese Internet was viewed as a backwater of counterfeit products devoid of innovation. The Chinese version of Google was a highly controversial experiment in online diplomacy. To get to China, a young company that chose the motto “Do not be evil” agreed to censor search results for Chinese users.

Central to this decision took a bet on the fact that even a censored Google product may expand the horizons of Chinese users and push the Chinese Internet to be more open.

At first, Google seemed to succeed in this mission. When Chinese users searched for censored content in google.cn, they saw a notification that some results were deleted. This public recognition of Internet censorship was the first among Chinese search engines, and the authorities did not like it.

“The Chinese government hated it,” said Kaiser Kuo, the former head of Baidu’s international communications department. “They compared this to a guest who comes to dinner and says:“ I will agree to eat the food, but I don’t like it ”.” Google did not ask the government for such notification, but did not receive instructions to remove it. On the side of the company played the world prestige and technical expertise. China could be a promising market, but still depended on Silicon Valley in terms of talent, funding and knowledge. Yes, Google wanted to work in China, but China needed Google.

Google’s censorship notice was a modest victory for democracy. Soon Baidu and other search engines in China followed suit. Over the next four years, Google China fought on several fronts: with the Chinese government due to content restrictions from local rival Baidu search results in quality and with its own leadership in Mountain View for the right to adapt global products to local needs. By the end of 2009, Google controlled more than a third of the Chinese search market - a considerable share, but is significantly lower than 58% for Baidu, according to Analysys International.

The Chinese government has cracked down on political free-thinking in 2013 when there were massive landing of the opposition and have passed legislation against "spreading rumors" on the Internet: two punch that strangled political debate.

However, no censorship or competition forced Google to leave China. There was a powerful hacker attack, known as "Operation Aurora", which affected all of Google intellectual property to the accounts of Chinese human rights activists on Gmail. The attack, which, according to Google, came from China, forced the company to take action. January 12, 2010, Google announced: "We have decided that we will no longer censor our results in google.cn, and so over the next few weeks to discuss with the Chinese government the legal basis on which the search engine can be operated without a filter, if possible ".

A sudden reversal stunned Chinese officials. Most Chinese Internet users could continue to live easy with a few reminders of government control, but Google's ad attracted general attention to cyber attacks and censorship. The world's largest Internet company and the government of the most densely populated country began a public showdown.

"[Chinese officials] really scared, and it looked like they were ready to run and hide in some cave, - says Kuo. - All the people who previously seemed to give a damn about Internet censorship, are now clearly angry. The entire Internet was buzzing. "

But officials refused to yield. "China welcomes the international Internet business developing services in China in accordance with the law," the Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said in a comment to Reuters. Government control of information has been and remains a central element of the doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party. In the six months before, after the riots in Xinjiang, the government in one fell swoop has blocked Facebook, Twitter and the YouTube, strengthening the so-called Great Chinese firewall. The government made a bet: China and its IT sector do not need a Google search to succeed.

Google soon abandoned google.cn, retreating to a Hong Kong search engine. In response, the Chinese government has decided not to completely block the company's services, leaving Gmail and Google Maps, and for a while even occasionally allowed access from the mainland to the search engine in Hong Kong. Both sides are deadlocked, although the tension persisted.

Google leaders seemed willing to wait out. "I personally believe that you can not build a modern knowledge society with a [censored], - said Google chairman Eric Schmidt in an interview with Foreign Policy in 2012. - Will such a regime fall after a sufficiently long time? I think yes, without a doubt. ”

But instead of suffering under the yoke of censorship, the Chinese Internet sector flourished. Between 2010 and 2015, there was an explosive growth of new products and companies. Xiaomi, a manufacturer of equipment with a current capitalization of $ 40 billion, was founded only in April 2010. A month earlier, Meituan appeared - a clone of Groupon, which turned into a giant of online offline services; he issued shares in September 2018 and now costs about $ 35 billion. Taxi service Didi ousted Uber from China, and now challenges it in international markets, founded in 2012. Chinese engineers and entrepreneurs who returned from Silicon Valley, including many former Googlers, played a decisive role in this revolution by bringing world-class technical and business solutions to the market, isolated from their former US employers. Older companies such as Baidu and Alibaba also grew rapidly during these years.

In 2017, the government launched a new repression against VPN-software, widely used to circumvent censorship.

The Chinese government played a controversial role in this process. It dealt with the political opposition in 2013, imprisoning critics and introducing new laws against “spreading rumors” on the Internet — an elegant two-way move that largely stifled political debate on once-loud social networking sites. However, it also launched a resounding campaign to promote "mass entrepreneurship and mass innovation." State-funded start-up incubators have spread throughout the country, as has state-supported venture capital.

This merging of forces brought results. Services like Meituan flourished. Like Tencent's WeChat super-app, the “Digital Swiss Army Knife,” which combines aspects of WhatsApp, PayPal, and dozens of other apps from the West. Alibaba, the e-commerce giant, entered the New York Stock Exchange in September 2014, selling $ 25 billion worth of shares - still the record IPO in world history.

In the wake of this success, the Chinese government decided to break the difficult truce with Google. In the middle of 2014, a few months before the Alibaba IPO, the government blocked virtually all Google services in China, including many that are deemed necessary for international business, such as Gmail, Google Maps and Google Scholar. “It caught us by surprise because we felt that Google was one of those valuable assets [that they cannot afford to block],” said Charlie Smith, the pseudonymous co-founder of GreatFire, which tracks the Chinese firewall and helps circumvent censorship.

The Chinese government unexpectedly won on all fronts: it blocked the giants of Silicon Valley, censored the political opposition - and at the same time maintained control over the profitable and innovative Internet sector.

When the Chinese Internet flourished and the government did not retreat, Google began looking for options to return to China. With mixed success, she tried to promote less politically sensitive products besides searching.

In 2015, it was rumored that Google was close to returning the Google Play catalog to China, and was awaiting approval from the Chinese government, but the rumors never materialized. This was followed by a partnership with Mobvoi, a Chinese smart watch manufacturer founded by a former Google employee. The joint project was supposed to make voice search on Android Wear available in China. Later, Google invested in Mobvoi, making the first direct investment in China since 2010.

In March 2017, there were reports that authorities will unlock Google Scholar. They did not. Messages that Google will launch a catalog of mobile applications with the Chinese company NetEase, also disappeared. However, Google allowed to re-launch the mobile translator.

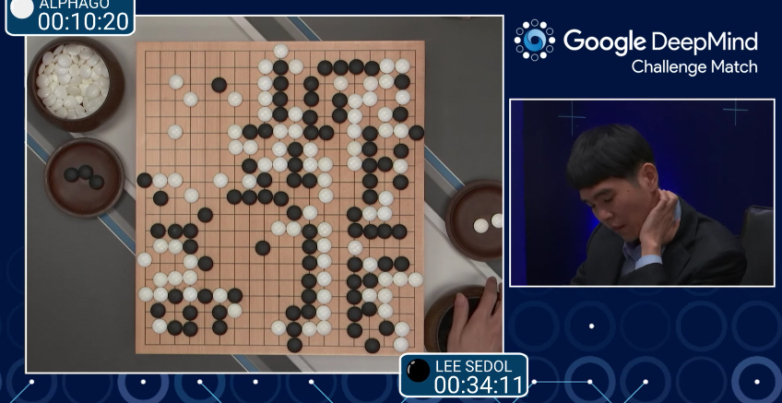

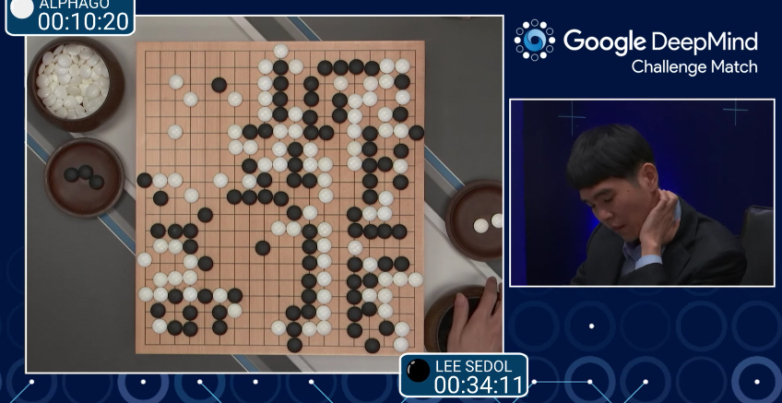

Then an interesting event took place. In May 2017, there was a match between AlphaGo, the program for the game Go from the sister company DeepMind, and Ke Jie, the number one player in the world. The match was allowed in Wuchcheng, a tourist suburb of Shanghai. AlphaGo won all three games. Perhaps the government foresaw such a result. The live broadcast of the match in China was banned, and not only by video: as The Guardian wrote, “viewers were not allowed to cover the match live in any way, including text comments, social networks or push notifications.” DeepMind broadcast the match outside of China.

During the same period, the Chinese censors quietly rolled back some of the democratic achievements of previous years. In 2016, the Chinese search engines removed the notifications about censorship of search results, first introduced by Google. In 2017, the government launched a new VPN suppression mechanism. Meanwhile, the Chinese authorities began to introduce advanced surveillance technologies using artificial intelligence across the country, building what some have called the “21st century police state” in the western region of Xinjiang, where Muslim Uighurs live (this area is compared to the Soviet GULAG). . trans.).

Map of Xinjiang and border areas

Despite the retrograde atmosphere, Google completed 2017 with a major announcement, opening a new AI research center in Beijing. The new center will be supervised by Fei-Fei Lee, the lead researcher for Google Cloud, originally from China: “The science of AI knows no boundaries,” she wrote in the announcement of the launch of the Center. “Like its advantages.” (In September 2018, Professor Lee left Google and returned to Stanford University).

The research center is a public symbol of Google’s ongoing efforts to establish itself in China. But besides public actions, Google took some covert actions to adapt to Chinese government restrictions. Chinese officials were shown a prototype of the censored search engine Dragonfly with a black list of keywords: it was assumed that it would be launched as part of a joint venture with an unnamed Chinese partner. From the documents obtained by The Intercept , it follows that the search engine still had to inform users about the facts of censorship.

Other aspects of the project were of particular concern. It was reported that the prototype of the application links user search requests with mobile phone numbers, opening the door for total surveillance and, possibly, arrests, if people are looking for prohibited materials.

In his speech to the Dragonfly team, which was later leaked to the media, the head of Google’s search division, Ben Gomez, explained the company's objectives. According to him, China is “perhaps the most interesting market in the world.” Google was not just trying to make money in China, but was also striving for something more: “We need to understand what is happening there for our own inspiration,” he said. “China will teach us what we don’t know.”

In early December, Google CEO Sundar Pichai told a congressional committee that "we now have no plans to launch in China," although he did not rule out such plans for the future. The question is, if Google wants to come back, will China let them go?

To answer this question, try meditating as advisor to President Xi Jinping.

The return of Google search certainly has its advantages. A growing number of knowledge workers in China need access to global news and research, and Baidu is not looking well outside of China. Google can serve as a valuable partner for Chinese companies seeking international involvement, as demonstrated by a patent exchange partnership with Tencent and an investment of $ 550 million in e-commerce giant JD. The return of Google will also help legitimize the Communist Party’s approach to Internet governance: this is a signal that China is an indispensable market - and open - as long as you are “playing by the rules.”

But from the point of view of the Chinese government, these potential advantages are insignificant. Chinese citizens who need access to the global Internet can still get it via VPN (although this is becoming increasingly difficult). Google does not have to do business in China to help Chinese Internet giants conduct business abroad. And the giants of Silicon Valley have already ceased to publicly criticize Chinese Internet censorship, and instead praise the country's dynamism and innovation.

On the other hand, the return of Google carries threatening political risks. In American political circles, there is a growing hostility towards both China and Silicon Valley. Returning to China triggers political pressure on Google. What if this pressure — through antitrust or new legislation — actually forces a company to choose between the American and Chinese markets? The sudden departure of Google in 2010 was a serious loss of face for the Chinese government in the eyes of its citizens. If Chinese leaders give the green light to the Dragonfly project, they risk repeating the situation.

Most likely, an experienced adviser will decide that these risks to Xi Jinping, the Communist Party and his own career outweigh the modest benefits of returning to Google. Now the Chinese government controls the technology sector, which is profitable, innovative, and is mainly managed by domestic companies - this is an excellent position. The return of Google will reduce these leverage. Then it is better to stick to the status quo: lure the prospect of full access to the market and throw random bones to Silicon Valley companies, allowing minor services such as Google Translate.

Google has one trump card. She first appeared in China during the time of desktop computers, and left at the dawn of the mobile Internet, but now she is trying to return to the AI era. The Chinese government has high hopes for AI as a universal tool of economic activity, military power and social management, including monitoring the population. Both Google and its sister company Alphabet DeepMind are world leaders in AI research.

This is probably why Google holds public events such as the AlphaGo match and the game “Guess the picture” in WeChat, as well as taking more serious steps, such as the creation of Beijing’s AI laboratory and the promotion of TensorFlow in the Chinese market — the software library for artificial intelligence Google Brain. Taken together, these efforts represent a kind of lobbying strategy of artificial intelligence, designed to influence the Chinese leadership.

However, these steps are faced with opposition from at least three sides: Beijing; Washington and Mountain View.

The Chinese leaders have every reason to believe that they already have everything they need. They can use software development tools like TensorFlow and they have a prestigious Google research lab to train Chinese AI researchers, so it’s not necessary to give Google access to the market.

Meanwhile, in Washington, security officials are annoyed that Google is actively courting a geopolitical adversary, refusing to work with the Pentagon on AI projects, because Google employees object to their work being used for military purposes.

The own staff is the key to the third battlefield. Employees have already demonstrated the ability to quickly and efficiently mobilize, as in the case of protests against US defense contracts. At the end of November 2018, more than 600 Googlers signed an open letter demanding that the company abandon the Dragonfly project: “We object to technologies that help the strong oppress the weak.” Despite all the problems, the top leadership of Google has not completely abandoned its plans. Although the development of Dragonfly has stalled, the wealth and dynamism of the Chinese market attract Google. But now no longer Google decides.

“I know that people in Silicon Valley are really smart and really successful because they can solve any problem they encounter,” said Bill Bishop, a digital media entrepreneur with experience in both markets. “But I don’t think they ever encountered a problem like the Chinese Communist Party.”

Google’s first foray into Chinese markets was a short-lived experiment. Google China search system launched in 2006, and four years later it suddenly shut down for mainland China after a major hacking and disputes over censorship of search results. But in August 2018 investigative journalism website The Intercept reported that the company is secretly working on a prototype of a new censored search engine for China under the name of Project Dragonfly.

Google’s first foray into Chinese markets was a short-lived experiment. Google China search system launched in 2006, and four years later it suddenly shut down for mainland China after a major hacking and disputes over censorship of search results. But in August 2018 investigative journalism website The Intercept reported that the company is secretly working on a prototype of a new censored search engine for China under the name of Project Dragonfly.Against the backdrop of protest by human rights defenders and some Google employees, Vice President Mike Pence called on the company to stop working on Dragonfly. He said that the system "will increase the censorship of the Communist Party and endanger the confidentiality of users." In mid-December, The Intercept reported that Google had suspended the development of Dragonfly after claims of its own privacy department, which had learned about the project from the media.

')

Some observers say that the decision to return to the world's largest market depends from Google: if it will compromise with his principles and expose censored search as China wants? But observers overlook the most important thing: this time the decision will be made by the Chinese government.

Google and China have suffered in a strange waltz for more than ten years, constantly fighting for who leads and who follows. The history of this dance demonstrates the main changes in China’s relationship with Google and the entire Silicon Valley. To understand whether China will allow Google to return to the market, we need to understand how Google and China were in such a situation, what incentives faced by each party - and how artificial intelligence can make them both dance to a new tune.

Do the right thing?

When the www.google.cn opened in 2006, the company just turned two years old. The iPhone did not yet exist, like Android smartphones, and the Chinese Internet was viewed as a backwater of counterfeit products devoid of innovation. The Chinese version of Google was a highly controversial experiment in online diplomacy. To get to China, a young company that chose the motto “Do not be evil” agreed to censor search results for Chinese users.

Central to this decision took a bet on the fact that even a censored Google product may expand the horizons of Chinese users and push the Chinese Internet to be more open.

At first, Google seemed to succeed in this mission. When Chinese users searched for censored content in google.cn, they saw a notification that some results were deleted. This public recognition of Internet censorship was the first among Chinese search engines, and the authorities did not like it.

“The Chinese government hated it,” said Kaiser Kuo, the former head of Baidu’s international communications department. “They compared this to a guest who comes to dinner and says:“ I will agree to eat the food, but I don’t like it ”.” Google did not ask the government for such notification, but did not receive instructions to remove it. On the side of the company played the world prestige and technical expertise. China could be a promising market, but still depended on Silicon Valley in terms of talent, funding and knowledge. Yes, Google wanted to work in China, but China needed Google.

Google’s censorship notice was a modest victory for democracy. Soon Baidu and other search engines in China followed suit. Over the next four years, Google China fought on several fronts: with the Chinese government due to content restrictions from local rival Baidu search results in quality and with its own leadership in Mountain View for the right to adapt global products to local needs. By the end of 2009, Google controlled more than a third of the Chinese search market - a considerable share, but is significantly lower than 58% for Baidu, according to Analysys International.

The Chinese government has cracked down on political free-thinking in 2013 when there were massive landing of the opposition and have passed legislation against "spreading rumors" on the Internet: two punch that strangled political debate.

However, no censorship or competition forced Google to leave China. There was a powerful hacker attack, known as "Operation Aurora", which affected all of Google intellectual property to the accounts of Chinese human rights activists on Gmail. The attack, which, according to Google, came from China, forced the company to take action. January 12, 2010, Google announced: "We have decided that we will no longer censor our results in google.cn, and so over the next few weeks to discuss with the Chinese government the legal basis on which the search engine can be operated without a filter, if possible ".

A sudden reversal stunned Chinese officials. Most Chinese Internet users could continue to live easy with a few reminders of government control, but Google's ad attracted general attention to cyber attacks and censorship. The world's largest Internet company and the government of the most densely populated country began a public showdown.

"[Chinese officials] really scared, and it looked like they were ready to run and hide in some cave, - says Kuo. - All the people who previously seemed to give a damn about Internet censorship, are now clearly angry. The entire Internet was buzzing. "

But officials refused to yield. "China welcomes the international Internet business developing services in China in accordance with the law," the Foreign Ministry spokeswoman said in a comment to Reuters. Government control of information has been and remains a central element of the doctrine of the Chinese Communist Party. In the six months before, after the riots in Xinjiang, the government in one fell swoop has blocked Facebook, Twitter and the YouTube, strengthening the so-called Great Chinese firewall. The government made a bet: China and its IT sector do not need a Google search to succeed.

Google soon abandoned google.cn, retreating to a Hong Kong search engine. In response, the Chinese government has decided not to completely block the company's services, leaving Gmail and Google Maps, and for a while even occasionally allowed access from the mainland to the search engine in Hong Kong. Both sides are deadlocked, although the tension persisted.

Google leaders seemed willing to wait out. "I personally believe that you can not build a modern knowledge society with a [censored], - said Google chairman Eric Schmidt in an interview with Foreign Policy in 2012. - Will such a regime fall after a sufficiently long time? I think yes, without a doubt. ”

Changing roles

But instead of suffering under the yoke of censorship, the Chinese Internet sector flourished. Between 2010 and 2015, there was an explosive growth of new products and companies. Xiaomi, a manufacturer of equipment with a current capitalization of $ 40 billion, was founded only in April 2010. A month earlier, Meituan appeared - a clone of Groupon, which turned into a giant of online offline services; he issued shares in September 2018 and now costs about $ 35 billion. Taxi service Didi ousted Uber from China, and now challenges it in international markets, founded in 2012. Chinese engineers and entrepreneurs who returned from Silicon Valley, including many former Googlers, played a decisive role in this revolution by bringing world-class technical and business solutions to the market, isolated from their former US employers. Older companies such as Baidu and Alibaba also grew rapidly during these years.

In 2017, the government launched a new repression against VPN-software, widely used to circumvent censorship.

The Chinese government played a controversial role in this process. It dealt with the political opposition in 2013, imprisoning critics and introducing new laws against “spreading rumors” on the Internet — an elegant two-way move that largely stifled political debate on once-loud social networking sites. However, it also launched a resounding campaign to promote "mass entrepreneurship and mass innovation." State-funded start-up incubators have spread throughout the country, as has state-supported venture capital.

This merging of forces brought results. Services like Meituan flourished. Like Tencent's WeChat super-app, the “Digital Swiss Army Knife,” which combines aspects of WhatsApp, PayPal, and dozens of other apps from the West. Alibaba, the e-commerce giant, entered the New York Stock Exchange in September 2014, selling $ 25 billion worth of shares - still the record IPO in world history.

In the wake of this success, the Chinese government decided to break the difficult truce with Google. In the middle of 2014, a few months before the Alibaba IPO, the government blocked virtually all Google services in China, including many that are deemed necessary for international business, such as Gmail, Google Maps and Google Scholar. “It caught us by surprise because we felt that Google was one of those valuable assets [that they cannot afford to block],” said Charlie Smith, the pseudonymous co-founder of GreatFire, which tracks the Chinese firewall and helps circumvent censorship.

The Chinese government unexpectedly won on all fronts: it blocked the giants of Silicon Valley, censored the political opposition - and at the same time maintained control over the profitable and innovative Internet sector.

Trojan horse AlphaGo

When the Chinese Internet flourished and the government did not retreat, Google began looking for options to return to China. With mixed success, she tried to promote less politically sensitive products besides searching.

In 2015, it was rumored that Google was close to returning the Google Play catalog to China, and was awaiting approval from the Chinese government, but the rumors never materialized. This was followed by a partnership with Mobvoi, a Chinese smart watch manufacturer founded by a former Google employee. The joint project was supposed to make voice search on Android Wear available in China. Later, Google invested in Mobvoi, making the first direct investment in China since 2010.

In March 2017, there were reports that authorities will unlock Google Scholar. They did not. Messages that Google will launch a catalog of mobile applications with the Chinese company NetEase, also disappeared. However, Google allowed to re-launch the mobile translator.

Then an interesting event took place. In May 2017, there was a match between AlphaGo, the program for the game Go from the sister company DeepMind, and Ke Jie, the number one player in the world. The match was allowed in Wuchcheng, a tourist suburb of Shanghai. AlphaGo won all three games. Perhaps the government foresaw such a result. The live broadcast of the match in China was banned, and not only by video: as The Guardian wrote, “viewers were not allowed to cover the match live in any way, including text comments, social networks or push notifications.” DeepMind broadcast the match outside of China.

During the same period, the Chinese censors quietly rolled back some of the democratic achievements of previous years. In 2016, the Chinese search engines removed the notifications about censorship of search results, first introduced by Google. In 2017, the government launched a new VPN suppression mechanism. Meanwhile, the Chinese authorities began to introduce advanced surveillance technologies using artificial intelligence across the country, building what some have called the “21st century police state” in the western region of Xinjiang, where Muslim Uighurs live (this area is compared to the Soviet GULAG). . trans.).

Map of Xinjiang and border areas

Despite the retrograde atmosphere, Google completed 2017 with a major announcement, opening a new AI research center in Beijing. The new center will be supervised by Fei-Fei Lee, the lead researcher for Google Cloud, originally from China: “The science of AI knows no boundaries,” she wrote in the announcement of the launch of the Center. “Like its advantages.” (In September 2018, Professor Lee left Google and returned to Stanford University).

The research center is a public symbol of Google’s ongoing efforts to establish itself in China. But besides public actions, Google took some covert actions to adapt to Chinese government restrictions. Chinese officials were shown a prototype of the censored search engine Dragonfly with a black list of keywords: it was assumed that it would be launched as part of a joint venture with an unnamed Chinese partner. From the documents obtained by The Intercept , it follows that the search engine still had to inform users about the facts of censorship.

Other aspects of the project were of particular concern. It was reported that the prototype of the application links user search requests with mobile phone numbers, opening the door for total surveillance and, possibly, arrests, if people are looking for prohibited materials.

In his speech to the Dragonfly team, which was later leaked to the media, the head of Google’s search division, Ben Gomez, explained the company's objectives. According to him, China is “perhaps the most interesting market in the world.” Google was not just trying to make money in China, but was also striving for something more: “We need to understand what is happening there for our own inspiration,” he said. “China will teach us what we don’t know.”

In early December, Google CEO Sundar Pichai told a congressional committee that "we now have no plans to launch in China," although he did not rule out such plans for the future. The question is, if Google wants to come back, will China let them go?

Chinese calculation

To answer this question, try meditating as advisor to President Xi Jinping.

The return of Google search certainly has its advantages. A growing number of knowledge workers in China need access to global news and research, and Baidu is not looking well outside of China. Google can serve as a valuable partner for Chinese companies seeking international involvement, as demonstrated by a patent exchange partnership with Tencent and an investment of $ 550 million in e-commerce giant JD. The return of Google will also help legitimize the Communist Party’s approach to Internet governance: this is a signal that China is an indispensable market - and open - as long as you are “playing by the rules.”

But from the point of view of the Chinese government, these potential advantages are insignificant. Chinese citizens who need access to the global Internet can still get it via VPN (although this is becoming increasingly difficult). Google does not have to do business in China to help Chinese Internet giants conduct business abroad. And the giants of Silicon Valley have already ceased to publicly criticize Chinese Internet censorship, and instead praise the country's dynamism and innovation.

On the other hand, the return of Google carries threatening political risks. In American political circles, there is a growing hostility towards both China and Silicon Valley. Returning to China triggers political pressure on Google. What if this pressure — through antitrust or new legislation — actually forces a company to choose between the American and Chinese markets? The sudden departure of Google in 2010 was a serious loss of face for the Chinese government in the eyes of its citizens. If Chinese leaders give the green light to the Dragonfly project, they risk repeating the situation.

Most likely, an experienced adviser will decide that these risks to Xi Jinping, the Communist Party and his own career outweigh the modest benefits of returning to Google. Now the Chinese government controls the technology sector, which is profitable, innovative, and is mainly managed by domestic companies - this is an excellent position. The return of Google will reduce these leverage. Then it is better to stick to the status quo: lure the prospect of full access to the market and throw random bones to Silicon Valley companies, allowing minor services such as Google Translate.

Google play

Google has one trump card. She first appeared in China during the time of desktop computers, and left at the dawn of the mobile Internet, but now she is trying to return to the AI era. The Chinese government has high hopes for AI as a universal tool of economic activity, military power and social management, including monitoring the population. Both Google and its sister company Alphabet DeepMind are world leaders in AI research.

This is probably why Google holds public events such as the AlphaGo match and the game “Guess the picture” in WeChat, as well as taking more serious steps, such as the creation of Beijing’s AI laboratory and the promotion of TensorFlow in the Chinese market — the software library for artificial intelligence Google Brain. Taken together, these efforts represent a kind of lobbying strategy of artificial intelligence, designed to influence the Chinese leadership.

However, these steps are faced with opposition from at least three sides: Beijing; Washington and Mountain View.

The Chinese leaders have every reason to believe that they already have everything they need. They can use software development tools like TensorFlow and they have a prestigious Google research lab to train Chinese AI researchers, so it’s not necessary to give Google access to the market.

Meanwhile, in Washington, security officials are annoyed that Google is actively courting a geopolitical adversary, refusing to work with the Pentagon on AI projects, because Google employees object to their work being used for military purposes.

The own staff is the key to the third battlefield. Employees have already demonstrated the ability to quickly and efficiently mobilize, as in the case of protests against US defense contracts. At the end of November 2018, more than 600 Googlers signed an open letter demanding that the company abandon the Dragonfly project: “We object to technologies that help the strong oppress the weak.” Despite all the problems, the top leadership of Google has not completely abandoned its plans. Although the development of Dragonfly has stalled, the wealth and dynamism of the Chinese market attract Google. But now no longer Google decides.

“I know that people in Silicon Valley are really smart and really successful because they can solve any problem they encounter,” said Bill Bishop, a digital media entrepreneur with experience in both markets. “But I don’t think they ever encountered a problem like the Chinese Communist Party.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/434602/

All Articles