Byte-machine for the fort (and not only) in Indian (Part 2)

Let's continue experiments with bytecode. This is a continuation of the article about the byte-machine in assembler, here is the first part .

In general, I planned in the second part to make the fort interpreter, and in the third - the fort compiler for this byte-machine. But the volume, which was obtained for the article, turned out to be very large. To make an interpreter, you need to expand the kernel (a set of byte commands), and implement: variables, string parsing, string input, dictionaries, dictionary lookup ... Well, at least the output of numbers should work. As a result, I decided to break the article about the interpreter into two. Therefore, in this article we will expand the core, we will define the variables, we will deduce the numbers. Further the approximate plan is as follows: the 3rd part is the interpreter, the 4th part is the compiler. And, of course, performance tests. They will be in the 4th or 5th article. These articles will be after the new year.

')

And who has not been afraid of the terrible assembler and byte-code - welcome under the cat! :)

To begin with, we will correct the errors. We assign the file extension .s, as is customary for GAS (thanks to mistergrim ). Then, replace int 0x80 with syscall and use 64-bit registers (thanks to qw1 ). In the beginning, I did not carefully read the call description and corrected only the registers ... and received a Segmentation fault. It turns out that everything changed for syscall, including the call numbers. sys_write for syscall is number 1, and sys_exit is 60. As a result, the bad, type and bye commands have the following form:

b_bad = 0x00 bcmd_bad: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 - stdout mov rsi, offset msg_bad_byte # mov rdx, msg_bad_byte_len # syscall # mov rax, 60 # № 1 - sys_exit mov rbx, 1 # 1 syscall # b_bye = 0x01 bcmd_bye: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 - stdout mov rsi, offset msg_bye # mov rdx, msg_bye_len # syscall # mov rax, 60 # № 60 - sys_exit mov rdi, 0 # 0 syscall # b_type = 0x80 bcmd_type: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 - stdout pop rdx pop rsi push r8 syscall # pop r8 jmp _next And one moment. Quite rightly written in the comments to the last article of berez and fpauk , that if you use the processor address in the bytecode, the bytecode depends on the platform. And in that example, the string address for “Hello, world!” Was specified in bytecode by value (using the command lit64). Of course, this is not necessary. But it was the easiest way to test a byte machine. I will not do this anymore, but I will receive the addresses of variables by other means: in particular, with the var command (more on this later).

Warm up

And now, as a warm-up, we will do all the basic integer arithmetic operations (+, -, *, /, mod, / mod, abs). We need them.

The code is so simple that I quote it in the spoiler without comment.

Arithmetic

b_add = 0x21 bcmd_add: pop rax add [rsp], rax jmp _next b_sub = 0x22 bcmd_sub: pop rax sub [rsp], rax jmp _next b_mul = 0x23 bcmd_mul: pop rax pop rbx imul rbx push rax jmp _next b_div = 0x24 bcmd_div: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rax jmp _next b_mod = 0x25 bcmd_mod: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rdx jmp _next b_divmod = 0x26 bcmd_divmod: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rdx push rax jmp _next b_abs = 0x27 bcmd_abs: mov rax, [rsp] or rax, rax jge _next neg rax mov [rsp], rax jmp _next Traditionally, in a fort, double precision operations are added to ordinary arithmetic and stack operations. Words for such operations usually begin with the symbol “2”: 2DUP, 2SWAP, etc. But we have standard arithmetic already 64 digits, and we will not make 128 just today :)

Next, add the basic stack operations (drop, swap, root, -root, over, pick, roll).

Stack operations

b_drop = 0x31 bcmd_drop: add rsp, 8 jmp _next b_swap = 0x32 bcmd_swap: pop rax pop rbx push rax push rbx jmp _next b_rot = 0x33 bcmd_rot: pop rax pop rbx pop rcx push rbx push rax push rcx jmp _next b_mrot = 0x34 bcmd_mrot: pop rcx pop rbx pop rax push rcx push rax push rbx jmp _next b_over = 0x35 bcmd_over: push [rsp + 8] jmp _next b_pick = 0x36 bcmd_pick: pop rcx push [rsp + 8*rcx] jmp _next b_roll = 0x37 bcmd_roll: pop rcx mov rbx, [rsp + 8*rcx] roll1: mov rax, [rsp + 8*rcx - 8] mov [rsp + 8*rcx], rax dec rcx jnz roll1 push rbx jmp _next And we will also make reading and writing commands in memory (fortov words @ and!). As well as their counterparts for another bit.

Reading and writing to memory

b_get = 0x40 bcmd_get: pop rcx push [rcx] jmp _next b_set = 0x41 bcmd_set: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], rax jmp _next b_get8 = 0x42 bcmd_get8: pop rcx movsx rax, byte ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set8 = 0x43 bcmd_set8: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], al jmp _next b_get16 = 0x44 bcmd_get16: pop rcx movsx rax, word ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set16 = 0x45 bcmd_set16: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], ax jmp _next b_get32 = 0x46 bcmd_get32: pop rcx movsx rax, dword ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set32 = 0x47 bcmd_set32: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], eax jmp _next We may still need comparison commands, and we will do them.

Comparison commands

# 0= b_zeq = 0x50 bcmd_zeq: pop rax or rax, rax jnz rfalse rtrue: push -1 jmp _next rfalse: push 0 jmp _next # 0< b_zlt = 0x51 bcmd_zlt: pop rax or rax, rax jl rtrue push 0 jmp _next # 0> b_zgt = 0x52 bcmd_zgt: pop rax or rax, rax jg rtrue push 0 jmp _next # = b_eq = 0x53 bcmd_eq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jz rtrue push 0 jmp _next # < b_lt = 0x54 bcmd_lt: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jl rtrue push 0 jmp _next # > b_gt = 0x55 bcmd_gt: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jg rtrue push 0 jmp _next # <= b_lteq = 0x56 bcmd_lteq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jle rtrue push 0 jmp _next # >= b_gteq = 0x57 bcmd_gteq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jge rtrue push 0 jmp _next We will not test the operation. The main thing that the assembler would not give when compiling errors. Debugging will be in the process of using them.

Immediately make the word depth (stack depth). To do this, at the start, save the initial values of the data stack and the return stack. These values can still be useful when restarting the system.

init_stack: .quad 0 init_rstack: .quad 0 _start: mov rbp, rsp sub rbp, stack_size lea r8, start mov init_stack, rsp mov init_rstack, rbp jmp _next b_depth = 0x38 bcmd_depth: mov rax, init_stack sub rax, rsp shr rax, 3 push rax jmp _next Output numbers

Well, the warm-up is over, and you have to sweat a little. Let's teach our system to display numbers. To output numbers in the fort, the word "." (point). We do it the way it is done in standard implementations of the fort, using the words <#, hold, #, #s, #>, base. We'll have to realize all these words. A buffer and a pointer to the character being formed are used to form the number; these will be the words holdbuf and holdpoint.

So, we need these words:

- holdbuf - a buffer for forming the representation of a number, the formation takes place from the end

- holdpoint - address to the last displayed character (in holdbuf)

- <# - the beginning of the formation of a number; sets holdpoint to byte, after last byte holdbuf

- hold - decreases holdpoint by 1 and saves the character from the stack to the buffer at the received address

- # - divides the word at the top of the stack into the base of the number system, the remainder of the division translates into a character and saves it to the buffer using hold

- #s - converts the entire word; actually calls the word # in a loop until 0 is left on the stack

- #> - completion of the conversion; pushes the beginning of the formed string and its length onto the stack

We will do all the words on the byte-code, but first we will deal with variables.

Variables

And here there will be some Fort magic. The fact is that in a fort a variable is a word. When executing this word, the stack contains the address of the memory cell that stores the value of the variable. At this address you can read or write. For example, to write the value 12345 in variable A, you need to execute the following commands: “12345 A!”. In this example, 12345 is pushed onto the stack, then the variable A puts its address, and the word "!" removes two values from the stack and writes 12345 to variable A. In typical implementations of a fort (with direct-stitched code), the variables are a microprocessor command CALL with the _next address, after which a space is reserved for storing the variable value. When executing such a word, the microprocessor transfers control to _next and pushes the return address (on the RSP) onto the stack. But in the forte the microprocessor stack is arithmetic, and we will not return anywhere. As a result, execution continues, and in the stack is the address of the variable. And all this is one processor team! On an assembler, it would look like this:

call _next # _next, , 12345 .quad 12345 But we have a byte code, and we can not use this mechanism! I did not immediately figure out how to make such a mechanism on bytecode. But, if you think logically, nothing prevents you from implementing something very similar. You just have to take into account that this will not be a processor command, but a bytecode, more precisely, a “subroutine” bytecode. Here is the statement of the problem:

- this is a byte code, when transferring control to which you should immediately return from it

- after return, in the arithmetic stack should remain the address where the value of the variable is stored

We have an exit byte command. We make a word on the bytecode containing a single exit command. Then this command will return from it. It remains to make the same command, which additionally puts on the stack the address of the next byte (register R8). Let's do this as an additional entry point to exit, which would save on the transition:

b_var0 = 0x28 bcmd_var0: push r8 b_exit = 0x17 bcmd_exit: mov r8, [rbp] add rbp, 8 _next: movzx rcx, byte ptr [r8] inc r8 jmp [bcmd + rcx*8] Now the base variable will look like this:

base: .byte b_var0 .quad 10 By the way, why var0 and not just var? The fact is that there will be other commands for defining more advanced words that contain data. I will tell you more in the following articles.

Now we are ready to conclude numbers. Let's start!

Words base, holdbuf, holdpoint

How the variables will be arranged is already decided. Therefore, the words base, holdbuf, holdpoint are such:

base: .byte b_var0 .quad 10 holdbuf_len = 70 holdbuf: .byte b_var0 .space holdbuf_len holdpoint: .byte b_var0 .quad 0 The size of the holdbuf buffer is 70. The maximum number of digits in a number is 64 (this is if you select a binary system). There is still a reserve of several characters to put, for example, a number sign and a space after it. We will check for buffer overflow, but for now let's not put extra characters into the buffer. Then you can make another diagnosis.

hold

Now you can make the word hold. On the fort, its code looks like this:

: hold holdpoint @ 1- dup holdbuf > if drop drop else dup holdpoint ! c! then ; For those who see the fort for the first time, I will analyze the code in detail. For the following words I will not do this.

At the beginning there is a word for defining new words and the name of a new word: ": hold". After that comes the code, which ends with the word ";". Let's sort the code of the word. I will give the command and the state of the stack after the command is executed. Before calling a word on the stack, there is a character code that is placed in the buffer (indicated by <symbol>). Further it turns out so:

holdpoint <> < holdpoint> @ <> < holdpoint> 1- <> < holdpoint 1> dup <> < holdpoint 1> < holdpoint 1> holdbuf <> < holdpoint 1> < holdpoint 1> < holdbuf> > <> < holdpoint 1> <, holdpoint 1 holdbuf> After this is the if command, which is compiled into a conditional transition to a sequence of commands between else and then. A conditional transition removes the comparison result from the stack and performs the transition if there was a lie on the stack. If there was no transition, then there is a branch between if and else, in which there are two drop commands that remove the symbol and address. Otherwise, execution continues. The word "!" saves the new value to the holdpoint (the address and value are removed from the stack). And the word “c!” Writes the character to the buffer, this is the set8 byte-command (the address and the value of the character are removed from the stack).

dup <> < holdpoint 1> < holdpoint 1> holdpoint <> < holdpoint 1> < holdpoint 1> < holdpoint> ! <> < holdpoint 1> c! , , ! :) This is how much action this short sequence of commands does! Yes, the fort is laconic. And now we turn on the manual “compiler” in the head :) And compile it all into bytecode:

hold: .byte b_call8 .byte holdpoint - . - 1 # holdpoint .byte b_get # @ .byte b_wm # 1- .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_call8 .byte holdbuf - . - 1 # holdbuf .byte b_gt # > .byte b_qbranch8 # if .byte 0f - . .byte b_drop # drop .byte b_drop # drop .byte b_branch8 # ( then) .byte 1f - . 0: .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_call8 .byte holdpoint - . - 1 # holdpoint .byte b_set # ! .byte b_set8 # c! 1: .byte b_exit # ; Here I used local labels (0 and 1). These labels can be accessed by special names. For example, label 0 can be accessed by name 0f or 0b. This means a link to the nearest tag 0 (forward or backward). It is quite convenient for tags that are used locally, so as not to come up with different names.

Word #

Make the word #. On the fort, its code will look like this:

: # base /mod swap dup 10 < if c″ 0 + else 10 - c″ A + then hold ; The condition here is used to check: is the resulting figure less than ten? If it is less, numbers 0–9 are used; otherwise, characters starting with “A” are used. This will allow you to work with the hexadecimal number system. The c ″ 0 sequence pushes the character 0 code onto the stack. We include the “compiler”:

conv: .byte b_call16 .word base - . - 2 # base .byte b_get # @ .byte b_divmod # /mod .byte b_swap # swap .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_lit8 .byte 10 # 10 .byte b_lt # < .byte b_qnbranch8 # if .byte 0f - . .byte b_lit8 .byte '0' # c″ 0 .byte b_add # + .byte b_branch8 # else .byte 1f - . 0: .byte b_lit8 .byte 'A' # c″ A .byte b_add # + 1: .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 # hold .byte b_exit # ; Word <#

The word <# is quite simple:

: <# holdbuf 70 + holdpoint ! ; Bytecode:

conv_start: .byte b_call16 .word holdbuf - . - 2 .byte b_lit8 .byte holdbuf_len .byte b_add .byte b_call16 .word holdpoint - . - 2 .byte b_set .byte b_exit Word #>

The word #> to complete the conversion looks like this:

: #> holdpoint @ holdbuf 70 + over - ; Bytecode:

conv_end: .byte b_call16 .word holdpoint - . - 2 .byte b_get .byte b_call16 .word holdbuf - . - 2 .byte b_lit8 .byte holdbuf_len .byte b_add .byte b_over .byte b_sub .byte b_exit Word #s

And finally, the word #s:

: #s do # dup 0= until ; Bytecode:

conv_s: .byte b_call8 .byte conv - . - 1 .byte b_dup .byte b_qbranch8 .byte conv_s - . .byte b_exit Who is attentive, will notice here a slight discrepancy between the byte code and the code of the fort :)

All is ready

Now nothing will prevent the word "." From making a number:

: . <# #s drop #> type ; Bytecode:

dot: .byte b_call8 .byte conv_start - . - 1 .byte b_call8 .byte conv_s - . - 1 .byte b_drop .byte b_call8 .byte conv_end - . - 1 .byte b_type .byte b_exit Let's make a test byte code that checks our point:

start: .byte b_lit16 .word 1234 .byte b_call16 .word dot - . - 2 .byte b_bye Of course, it did not work all at once. But, after debugging, the following result was obtained:

$ as forth.asm -o forth.o -g -ahlsm>list.txt $ ld forth.o -o forth $ ./forth 1234bye! The jamb is visible immediately. After the number, the fort should display a space. Add after the call conv_start (<#) command 32 hold.

Still make a conclusion sign. At the beginning, we add dup abs, and at the end we check the sign of the left copy and place a minus if the number is negative (0 <if c ″ - hold then). As a result, the word "." takes the following form:

: . dup abs <# 32 hold #s drop #> 0< if c″ - hold then type ; Bytecode:

dot: .byte b_dup .byte b_abs .byte b_call8 .byte conv_start - . - 1 .byte b_lit8 .byte ' ' .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 .byte b_call8 .byte conv_s - . - 1 .byte b_drop .byte b_zlt .byte b_qnbranch8 .byte 1f - . .byte b_lit8 .byte '-' .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 1: .byte b_call8 .byte conv_end - . - 1 .byte b_type .byte b_exit In the starting sequence of byte commands, we put a negative number and check:

$ as forth.asm -o forth.o -g -ahlsm>list.txt $ ld forth.o -o forth $ ./forth -1234 bye! Output numbers there!

Full source

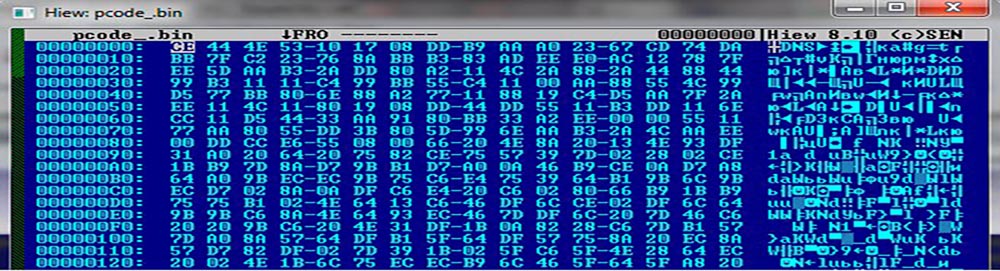

.intel_syntax noprefix stack_size = 1024 .section .data init_stack: .quad 0 init_rstack: .quad 0 msg_bad_byte: .ascii "Bad byte code!\n" msg_bad_byte_len = . - msg_bad_byte # len msg_bye: .ascii "bye!\n" msg_bye_len = . - msg_bye bcmd: .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bye, bcmd_num0, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad # 0x00 .quad bcmd_lit8, bcmd_lit16, bcmd_lit32, bcmd_lit64, bcmd_call8, bcmd_call16, bcmd_call32, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_branch8, bcmd_branch16, bcmd_qbranch8, bcmd_qbranch16, bcmd_qnbranch8, bcmd_qnbranch16,bcmd_bad, bcmd_exit # 0x10 .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_wm, bcmd_add, bcmd_sub, bcmd_mul, bcmd_div, bcmd_mod, bcmd_divmod, bcmd_abs # 0x20 .quad bcmd_var0, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_dup, bcmd_drop, bcmd_swap, bcmd_rot, bcmd_mrot, bcmd_over, bcmd_pick, bcmd_roll # 0x30 .quad bcmd_depth, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_get, bcmd_set, bcmd_get8, bcmd_set8, bcmd_get16, bcmd_set16, bcmd_get32, bcmd_set32 # 0x40 .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_zeq, bcmd_zlt, bcmd_zgt, bcmd_eq, bcmd_lt, bcmd_gt, bcmd_lteq, bcmd_gteq #0x50 .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad # 0x60 .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_type, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad # 0x80 .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad .quad bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad, bcmd_bad start: .byte b_lit16 .word -1234 .byte b_call16 .word dot - . - 2 .byte b_bye base: .byte b_var0 .quad 10 holdbuf_len = 70 holdbuf: .byte b_var0 .space holdbuf_len holdpoint: .byte b_var0 .quad 0 # : hold holdpoint @ 1- dup holdbuf > if drop drop else dup holdpoint ! c! then ; hold: .byte b_call8 .byte holdpoint - . - 1 # holdpoint .byte b_get # @ .byte b_wm # 1- .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_call8 .byte holdbuf - . - 1 # holdbuf .byte b_gt # > .byte b_qbranch8 # if .byte 0f - . .byte b_drop # drop .byte b_drop # drop .byte b_branch8 # ( then) .byte 1f - . 0: .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_call8 .byte holdpoint - . - 1 # holdpoint .byte b_set # ! .byte b_set8 # c! 1: .byte b_exit # ; # : # base /mod swap dup 10 < if c" 0 + else 10 - c" A + then hold ; conv: .byte b_call16 .word base - . - 2 # base .byte b_get # @ .byte b_divmod # /mod .byte b_swap # swap .byte b_dup # dup .byte b_lit8 .byte 10 # 10 .byte b_lt # < .byte b_qnbranch8 # if .byte 0f - . .byte b_lit8 .byte '0' # c" 0 .byte b_add # + .byte b_branch8 # else .byte 1f - . 0: .byte b_lit8 .byte '?' # c" A .byte b_add # + 1: .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 # hold .byte b_exit # ; # : <# holdbuf 70 + holdpoint ! ; conv_start: .byte b_call16 .word holdbuf - . - 2 .byte b_lit8 .byte holdbuf_len .byte b_add .byte b_call16 .word holdpoint - . - 2 .byte b_set .byte b_exit # : #s do # dup 0=until ; conv_s: .byte b_call8 .byte conv - . - 1 .byte b_dup .byte b_qbranch8 .byte conv_s - . .byte b_exit # : #> holdpoint @ holdbuf 70 + over - ; conv_end: .byte b_call16 .word holdpoint - . - 2 .byte b_get .byte b_call16 .word holdbuf - . - 2 .byte b_lit8 .byte holdbuf_len .byte b_add .byte b_over .byte b_sub .byte b_exit dot: .byte b_dup .byte b_abs .byte b_call8 .byte conv_start - . - 1 .byte b_lit8 .byte ' ' .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 .byte b_call8 .byte conv_s - . - 1 .byte b_drop .byte b_zlt .byte b_qnbranch8 .byte 1f - . .byte b_lit8 .byte '-' .byte b_call16 .word hold - . - 2 1: .byte b_call8 .byte conv_end - . - 1 .byte b_type .byte b_exit .section .text .global _start # _start: mov rbp, rsp sub rbp, stack_size lea r8, start mov init_stack, rsp mov init_rstack, rbp jmp _next b_var0 = 0x28 bcmd_var0: push r8 b_exit = 0x17 bcmd_exit: mov r8, [rbp] add rbp, 8 _next: movzx rcx, byte ptr [r8] inc r8 jmp [bcmd + rcx*8] b_num0 = 0x02 bcmd_num0: push 0 jmp _next b_lit8 = 0x08 bcmd_lit8: movsx rax, byte ptr [r8] inc r8 push rax jmp _next b_lit16 = 0x09 bcmd_lit16: movsx rax, word ptr [r8] add r8, 2 push rax jmp _next b_call8 = 0x0C bcmd_call8: movsx rax, byte ptr [r8] sub rbp, 8 inc r8 mov [rbp], r8 add r8, rax jmp _next b_call16 = 0x0D bcmd_call16: movsx rax, word ptr [r8] sub rbp, 8 add r8, 2 mov [rbp], r8 add r8, rax jmp _next b_call32 = 0x0E bcmd_call32: movsx rax, dword ptr [r8] sub rbp, 8 add r8, 4 mov [rbp], r8 add r8, rax jmp _next b_lit32 = 0x0A bcmd_lit32: movsx rax, dword ptr [r8] add r8, 4 push rax jmp _next b_lit64 = 0x0B bcmd_lit64: mov rax, [r8] add r8, 8 push rax jmp _next b_dup = 0x30 bcmd_dup: push [rsp] jmp _next b_wm = 0x20 bcmd_wm: decq [rsp] jmp _next b_add = 0x21 bcmd_add: pop rax add [rsp], rax jmp _next b_sub = 0x22 bcmd_sub: pop rax sub [rsp], rax jmp _next b_mul = 0x23 bcmd_mul: pop rax pop rbx imul rbx push rax jmp _next b_div = 0x24 bcmd_div: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rax jmp _next b_mod = 0x25 bcmd_mod: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rdx jmp _next b_divmod = 0x26 bcmd_divmod: pop rbx pop rax cqo idiv rbx push rdx push rax jmp _next b_abs = 0x27 bcmd_abs: mov rax, [rsp] or rax, rax jge _next neg rax mov [rsp], rax jmp _next b_drop = 0x31 bcmd_drop: add rsp, 8 jmp _next b_swap = 0x32 bcmd_swap: pop rax pop rbx push rax push rbx jmp _next b_rot = 0x33 bcmd_rot: pop rax pop rbx pop rcx push rbx push rax push rcx jmp _next b_mrot = 0x34 bcmd_mrot: pop rcx pop rbx pop rax push rcx push rax push rbx jmp _next b_over = 0x35 bcmd_over: push [rsp + 8] jmp _next b_pick = 0x36 bcmd_pick: pop rcx push [rsp + 8*rcx] jmp _next b_roll = 0x37 bcmd_roll: pop rcx mov rbx, [rsp + 8*rcx] roll1: mov rax, [rsp + 8*rcx - 8] mov [rsp + 8*rcx], rax dec rcx jnz roll1 push rbx jmp _next b_depth = 0x38 bcmd_depth: mov rax, init_stack sub rax, rsp shr rax, 3 push rax jmp _next b_get = 0x40 bcmd_get: pop rcx push [rcx] jmp _next b_set = 0x41 bcmd_set: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], rax jmp _next b_get8 = 0x42 bcmd_get8: pop rcx movsx rax, byte ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set8 = 0x43 bcmd_set8: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], al jmp _next b_get16 = 0x44 bcmd_get16: pop rcx movsx rax, word ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set16 = 0x45 bcmd_set16: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], ax jmp _next b_get32 = 0x46 bcmd_get32: pop rcx movsx rax, dword ptr [rcx] push rax jmp _next b_set32 = 0x47 bcmd_set32: pop rcx pop rax mov [rcx], eax jmp _next # 0= b_zeq = 0x50 bcmd_zeq: pop rax or rax, rax jnz rfalse rtrue: push -1 jmp _next rfalse: push 0 jmp _next # 0< b_zlt = 0x51 bcmd_zlt: pop rax or rax, rax jl rtrue push 0 jmp _next # 0> b_zgt = 0x52 bcmd_zgt: pop rax or rax, rax jg rtrue push 0 jmp _next # = b_eq = 0x53 bcmd_eq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jz rtrue push 0 jmp _next # < b_lt = 0x54 bcmd_lt: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jl rtrue push 0 jmp _next # > b_gt = 0x55 bcmd_gt: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jg rtrue push 0 jmp _next # <= b_lteq = 0x56 bcmd_lteq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jle rtrue push 0 jmp _next # >= b_gteq = 0x57 bcmd_gteq: pop rbx pop rax cmp rax, rbx jge rtrue push 0 jmp _next b_branch8 = 0x10 bcmd_branch8: movsx rax, byte ptr [r8] add r8, rax jmp _next b_branch16 = 0x11 bcmd_branch16: movsx rax, word ptr [r8] add r8, rax jmp _next b_qbranch8 = 0x12 bcmd_qbranch8: pop rax or rax, rax jnz bcmd_branch8 inc r8 jmp _next b_qbranch16 = 0x13 bcmd_qbranch16: pop rax or rax, rax jnz bcmd_branch16 add r8, 2 jmp _next b_qnbranch8 = 0x14 bcmd_qnbranch8: pop rax or rax, rax jz bcmd_branch8 inc r8 jmp _next b_qnbranch16 = 0x15 bcmd_qnbranch16:pop rax or rax, rax jz bcmd_branch16 add r8, 2 jmp _next b_bad = 0x00 bcmd_bad: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 — stdout mov rsi, offset msg_bad_byte # mov rdx, msg_bad_byte_len # syscall # mov rax, 60 # № 1 - sys_exit mov rbx, 1 # 1 syscall # b_bye = 0x01 bcmd_bye: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 — stdout mov rsi, offset msg_bye # mov rdx, msg_bye_len # syscall # mov rax, 60 # № 60 - sys_exit mov rdi, 0 # 0 syscall # b_type = 0x80 bcmd_type: mov rax, 1 # № 1 - sys_write mov rdi, 1 # № 1 - stdout pop rdx pop rsi push r8 syscall # pop r8 jmp _next Total

Now we have a pretty decent core of byte commands: all basic arithmetic, stack operations, comparison operations, work with memory, variables. Also, there is already an output of numbers, fully implemented in bytecode. Everything is ready, what would the interpreter do, which we will do in the next article!

Happy New Year, everyone!

Criticism is welcome! :)

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/433836/

All Articles