Optimization of relational databases without downtime on the example of the most loaded database in Badoo

Under highload conditions, the complexity of optimizing relational databases increases by an order of magnitude, since buying even more powerful hardware is expensive and it is no longer possible just to turn off the application at night for a long DB alter process and data migration.

Recently we told how we optimized the PHP code of our application . Now came the turn of the article about how we completely changed the internal structure of the most loaded and important database in Badoo, without losing a single query.

A patient

Users DataBase, or UDB is a service from which almost any request to Badoo begins. It solves several tasks: firstly, it is the central repository of basic user data for which authorization takes place (for example, email, user_id or facebook_id). In addition to storing this data, the service provides uniqueness control (so that two users with the same email, facebook_id, etc.) cannot register in the system. And the same service provides information on which of the thousands of shards all the other user data is in.

')

At the end of 2018, UDB stores data for more than 800 million users, who occupy about 1 TB on the disk. All this is served by pairs of MySQL master-slave servers in each of our data centers. In total, they process more than 140,000 requests per second.

The fall of UDB means the inaccessibility of all Badoo, since the code will not be able to find the shard on which user data rests. Therefore, it is subject to enormous demands for reliability and availability.

Because of this specificity, it is very expensive to make changes in the storage structure, so we approached the design of UDB very seriously in 2013. However, over time, the requirements as well as the load profile change. In an effort to adapt the system to new requirements and the level of load, many small and simple changes were made, but, unfortunately, such changes are far from being the most effective. And the day came when, instead of another hack or the purchase of expensive hardware, it was wiser to optimize more globally. Next we look at the main stages of this path.

Non-invasive optimizations

Any changes to the structure of a large and loaded database are quite expensive due to the complexity of the data migration process. Therefore, first of all, one should exhaust all optimization options that do not affect the data structure, but are limited to code and SQL queries. Perhaps this will be enough to remove the problem of excessive workload for a couple of years, which will allow you to do something more important for your business at this time.

The better you understand your system, the easier it will be for you to find approaches for such optimizations. Make sure you collect all the metrics that can help you. We are talking not only about system metrics like CPU usage and RAM usage or specific database metrics, but also about application-level application metrics, which is tied to an optimized database. How many requests per second for different types of operations? What is their response time? What is the size of the input and output data? It is by these metrics that you can judge the success of the performed optimizations. It is unlikely that you need optimization, which will slightly reduce the CPU usage on the database server, but at the same time will increase the response time of your application by a factor of ten.

By starting to collect additional application-level metrics for UDB, we were able to better understand which of the operations performed create 80% of the load and are the first candidates for learning, and which are used little or even no more.

A detailed analysis of the most frequent operation (retrieving users that meet certain criteria) showed that, despite the fact that all available user data are requested from the database, in reality, the application in 95% of cases uses only user_id. Simply highlighting this case into a separate API method that extracts only one column from the table, we were able to get the benefit from using the covering index and remove about 5% of the CPU load from the database server using this.

Analysis of another private operation showed that, despite the fact that it is performed for each HTTP request, in reality, the data that it retrieves is rarely used. We translated this query into a lazy model.

The main goal of metrics in the case of an optimization project is to better understand your database and find the most meaty pieces. It makes no sense to spend a lot of time and effort on optimizing queries that are less than 1% of your load profile. If you do not have metrics that allow you to understand your load profile, collect them. With such optimizations on the code side, we managed to remove about 15% of CPU usage from 80% of the database consumed.

Testing Ideas

If you are going to optimize a loaded database by changing its structure, you should start by testing your ideas on a test bench, since even optimization, which looks very promising in theory, in practice may not give a positive effect (and sometimes may even give a negative). And you hardly want to know about it only after a long migration of data on production.

The closer your booth configuration is to the production configuration, the more reliable you will get results. The important point is to ensure the correct load of the stand. Running random or same requests can lead to unreliable results. The best option is to use real requests from production. For UDB, we logged with production every tenth API read request (including parameters) in the form of a simple JSON log in the file. During the day we collected a log of 65 GB in size from 700 million requests.

We did not test the record, as compared with the number of requests for reading it is quite small and does not affect our workload. However, in your case this may not be the case. If you want to load the test bench with write requests, you will have to collect each request, since skipping write requests can lead to consistency errors on the test bench.

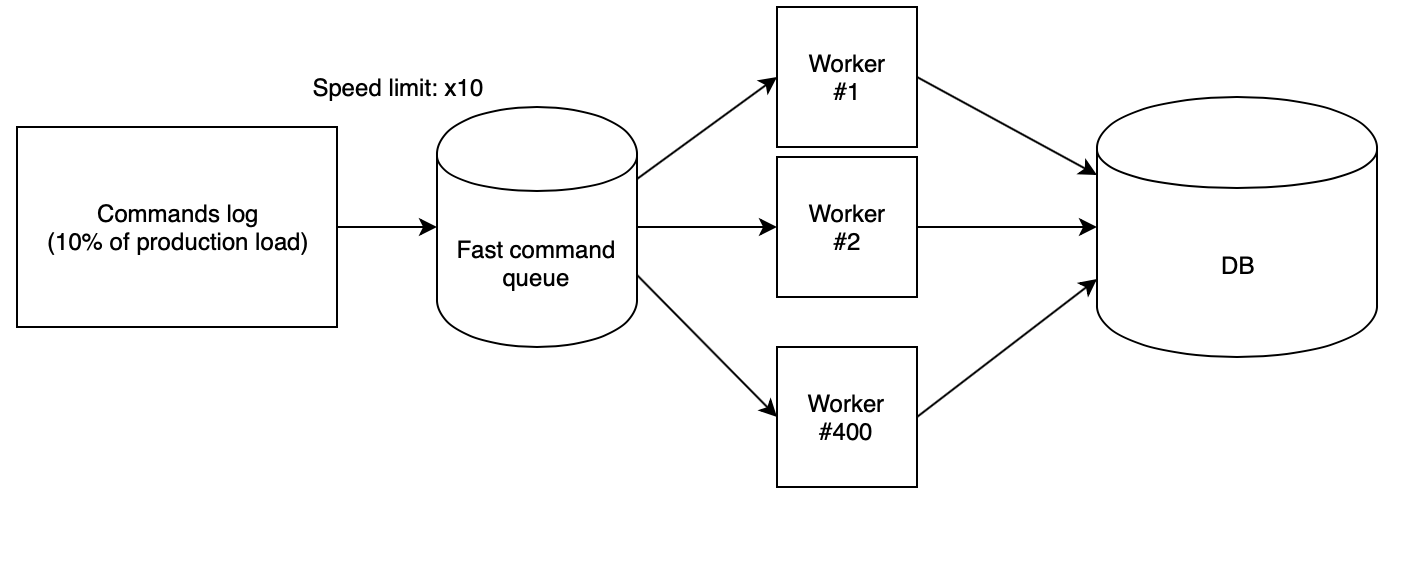

The next step is to correctly play the log on the stand. We used 400 PHP workers running from our script cloud , who read the collected log from the fast queue and consistently execute requests. In this case, the queue is filled with another script with a strictly defined speed. To test ideas, we used x10 speed, which multiplied by the fact that we collected only one out of ten requests from production, gave the same number of RPS as in production.

With such coefficients, it turns out that the day of production with all the pressure drops on the test bench passes in just two and a half hours.

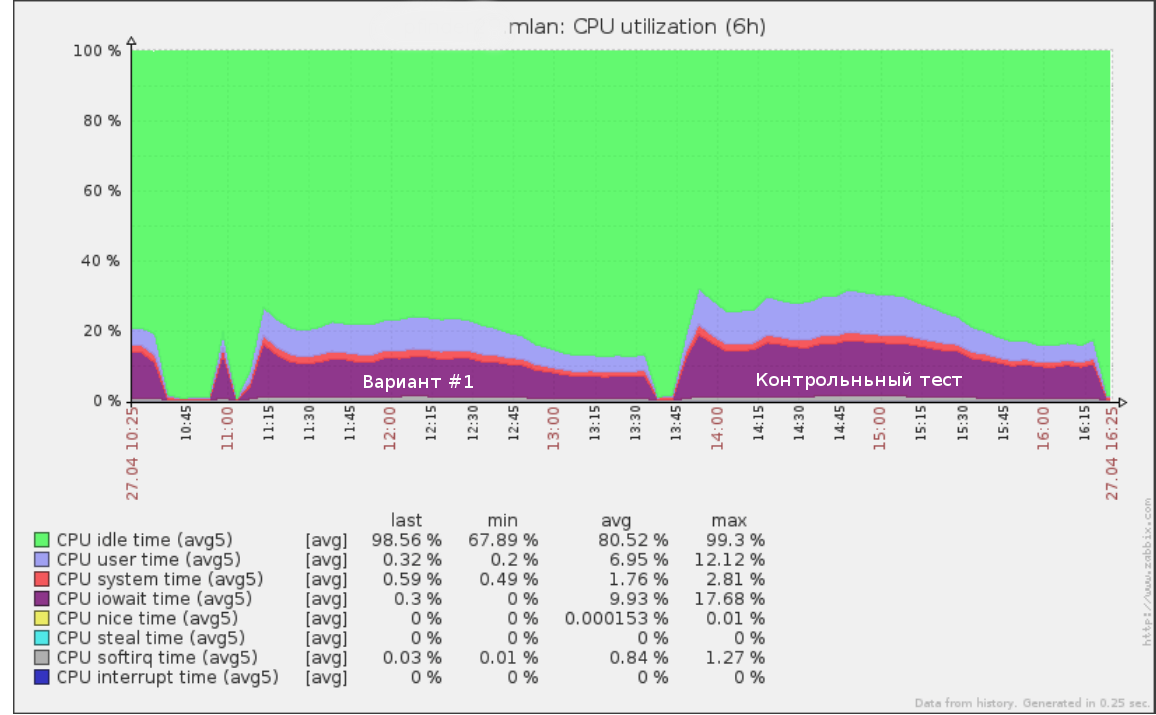

So, for example, the first test that we launched at a speed of x5 looked like (50% of the load from production) on the request log in half a day:

The same tool can be used to conduct a test for failure: increasing the speed (and therefore the RPS) until the base on the stand starts to degrade. This will give you a clear understanding of how much more your database can handle.

After testing the new data scheme, it is also important to conduct a test test on the original database structure. If its results and current performance in production differ greatly, first of all you need to understand the reasons. The test server may not be configured correctly and load testing data cannot be trusted.

It is also worth making sure that the new code works correctly. There is not much point in testing the performance of queries that do not perform the necessary work. You will benefit from integration tests that check whether the old and the new API return the same values for the same API calls.

After getting the results on all the ideas, all that remains is to select the options with the best ratio between price and quality and implement a new scheme in production.

Schema change

First of all, I’ll note that changing the data scheme without stopping the operation of the service is always quite difficult, expensive and risky. Therefore, if you have the opportunity to stop your application at the time of the structure change - just do it. In the case of UDB, we unfortunately could not afford this.

The second factor affecting the complexity of changing the scheme is the planned scale of changes. If all the proposed changes to the tables do not go beyond just an altera (for example, adding a pair of new indexes or columns), then they can be rotated with typical processes like pt-online-schema-change and gh-ost for MySQL or an alter slave with their subsequent replacement .

In our case, an excellent result was shown by vertical sharding of one giant table for about a dozen smaller with other columns and indices and data in another format. Such a transformation with standard tools is no longer implemented. So what to do?

We applied the following algorithm:

- We achieve a state when at the same time there are old and new schemes with actual data. The recording goes to both, and there is a guarantee of the consistency of the data in both versions. This item will be discussed in detail below.

- Gradually switch all reading to the new scheme, controlling the load.

- Turn off the record in the old scheme and delete it.

The main advantages of this approach are:

- security: there is the possibility of an instantaneous rollback right up to the last stage (we simply switch the reading back to the old circuit, if something went wrong);

- full load control during data migration;

- no heavy alter of the big table of the old scheme is required.

However, there are also disadvantages:

- the need to keep both versions of the diagrams on disk during the migration process (this can be a problem if you have little space and the table to be migrated is very large);

- a lot of time code to support the migration process, which will be sawn upon completion;

- it is possible to wash out the cache by reading from two schemes in parallel; there was a fear that the old and new versions would compete for RAM, which could lead to degradation of the service (in reality, this really created an additional burden, however, since the migration was carried out off-peak, it did not create problems for us).

The main difficulty in this algorithm is the first item. We will consider it in detail.

Sync changes

Migration of static data is not particularly difficult. However, what to do if you can’t just stop the whole record during the database migration?

There are several options to achieve synchronization of the new scheme: migration with log rolling and idempotent migration.

Migration snapshot data and then playing the log of the following changes

Each data update transaction is logged by a special table via triggers or at the application level, or the replication binlog is used as a log. After you have such a log, you can open a transaction and migrate data snapshot, while remembering the position in the log. Next, it remains to start using the collected log on the new scheme. Similarly, the popular MySQL backup tool Percona XtraBackup works, for example.

After the new scheme caught up to the current record, the most crucial stage begins: you still need to pause the recording in the old scheme for a short period of time and, making sure that the entire available log is applied to the new scheme, which means that the data between the schemes is consistent, application level to enable recording immediately in both sources.

The main disadvantages of this approach are that you will need to somehow store the log of operations, which in itself can create a load, in a complex switching process, and also in the probability of breaking the record if for some reason the schemes turn out to be inconsistent.

Idempotent record

The main idea of this approach is to start writing to the new scheme in parallel with writing to the old one before complete synchronization of changes, and then complete the migration of the remaining data. Similarly, new columns are usually filled in large tables.

Synchronous recording can be implemented both on DB triggers and in source code. I advise you to do this in the code, since in any case you will eventually have to write code that will write data to the new scheme, and implementing the migration on the code side will provide you with more control.

The important point to consider is that until the completion of the migration, the new scheme will be in inconsistent state. Because of this, a scenario is possible when updating a new table leads to a violation of the database database (foreign keys or a unique index), while from the point of view of the current scheme, the transaction is completely correct and must be completed.

This situation can lead to a rollback of good transactions due to the migration process. The simplest way to get around this problem is to add the IGNORE modifier to all requests to write data to a new scheme or intercept the rollback of such a transaction and run the version without writing to the new scheme.

The synchronization algorithm using idempotent writing in our case looks like this:

- We include writing to the new scheme in parallel with writing to the old one in compatibility mode (IGNORE).

- Run the script, which gradually bypasses the new scheme and fix inconsistent data. After that, the data in both tables should be synchronized, but this is inaccurate due to possible conflicts in clause 1.

- We launch the data consistency checker - we open a transaction and consistently read lines from the new and old schema comparing their correspondence.

- If there are conflicts, we finish and return to paragraph 3.

- After the checker showed that the data in both schemes are synchronized, then there should be no further discrepancies between the schemes, unless, of course, we missed some nuance. Therefore, we are waiting for some time (for example, a week) and launching a control check. If it shows that everything is good, then the task is completed successfully and you can translate the reading.

results

As a result of changing the data format, we were able to reduce the size of the main table from 544 GB to 226 GB, thereby reducing the load on the disk and increasing the amount of useful data that fit in the RAM.

Totally from the beginning of the project, using all the described approaches, we managed to reduce the CPU usage of the database server from 80% to 35% at peak traffic. The results of the subsequent load test showed that at the current rate of growth of the load, we can remain on the existing gland for at least three more years.

Splitting one huge table into somewhat simplified the process of conducting future alters in the database, and also significantly accelerated some of the scripts that collected data for BI.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/433730/

All Articles