Data consistency in high load systems

Problematics

Virtually any information system requires data storage on an ongoing basis. In most systems with low and medium load, this function is performed by relational DBMS, an indisputable advantage of which is the guarantee of data consistency.

A classic example explaining what data consistency is is the operation of transferring money from one account to another. At the moment when the operation of changing the balance of one account has already been completed, and the other has not yet had time, a failure may occur. Then the funds will be debited from one account, but not received to the other. This state of the data system is called mismatched, and, perhaps, there is no need to explain what consequences this may have. Relational DBMSs provide a transaction mechanism that ensures consistency of data at any time. A transaction is a finite set of operations that transfers one consistent state to another consistent state. In case of an error at any step, the DBMS cancels all previously performed operations and returns the data to the original consistent state. In other words - either all operations will be executed, or none.

As for large-scale systems, it is far from always possible to use a single database in them due to too much load. In such cases, each module of the system (service) is provided with its own separate database. In this case, the question arises as to for such a cluster architecture to ensure consistency of data.

')

Solving the problem of data consistency

One of the solutions is distributed transactions. First, all nodes in the cluster must agree that the operation is possible, then the changes are committed on all nodes. Since the nodes do not have any common storage device, the only way to reach a common opinion is to reach an agreement using some protocol of distributed consensus.

A simple protocol for committing global transactions is a two-phase commit (2PC). The node performing the transaction is considered the coordinator. At the prepare (prepare) phase, the coordinator informs the remaining nodes about the commit transaction and waits for them to confirm that they are ready to commit. If at least one node is not ready, the transaction is aborted. In the commit phase, the coordinator informs all nodes about the decision to commit the transaction. Upon receipt of confirmation from all that everything is ok, the coordinator also fixes the transaction.

Figure 1 - The general scheme of a two-phase commit

This protocol allows you to do a minimum of messages, but is not resistant to failures. For example, if the coordinator fails after the prepare phase, the remaining nodes have no information on whether the transaction should be committed or canceled (they will have to wait for the failure to be fixed). Another serious drawback of 2PC (and other protocols of distributed transactions, for example, 3PC) - with an increase in the number of cluster nodes, the performance of two-phase commits decreases.

Figure 2 - Dependence of the speed of a two-commit commit on the number of servers in a database cluster

In addition, the distributed transaction approach imposes a restriction: all modules of the system must use the same DBMS, which is not always convenient.

Another option is to provide a mechanism that allows you to work with different databases (for services) as with a single database (to solve the problem of data integrity in a distributed database). This requires some kind of transaction analogue for a distributed system ("business transaction").

In normal transactions, as well as in two-phase commits, all transactions are controlled by the transaction mechanism (using locks), and this is done to ensure that any operation can be rolled back (pessimistic approach - we consider any operation as potentially causing a failure). This is the bottleneck of the system. An alternative option is the so-called optimistic approach: we believe that most operations are completed successfully. Additional actions are already performed upon the failure that occurred. Those. we reduce costs for the majority of operations that leads to increase in productivity.

What is Saga (Saga) and how it works

An alternative to transactions for microservice architecture is Saga. Saga (saga) is a set of steps performed by various modules of the system (services); the saga service, which is responsible for the operation (business transaction) as a whole, is also required. Steps are linked through an event graph. After the saga is executed, the system should go from one agreed state to another (in case of successful execution), or return to the previous agreed state (in case of cancellation).

How to implement such a return or rollback of a business transaction? To do this, the sagas use a mechanism for canceling steps (compensating actions). For example, one of the steps was completed successfully (for example, an entry was added to the user database table), but one of the following steps failed and the whole saga should be canceled. Then the same service receives a command - cancel the action. But in the service DBMS, the local transaction is already completed, the user record has been added. Then, to return to the previous state, the service must perform a compensating action (in our example, delete the record). Cancellation of steps allows you to implement atomicity (“all or nothing”) within the framework of the saga - all steps are executed or compensated.

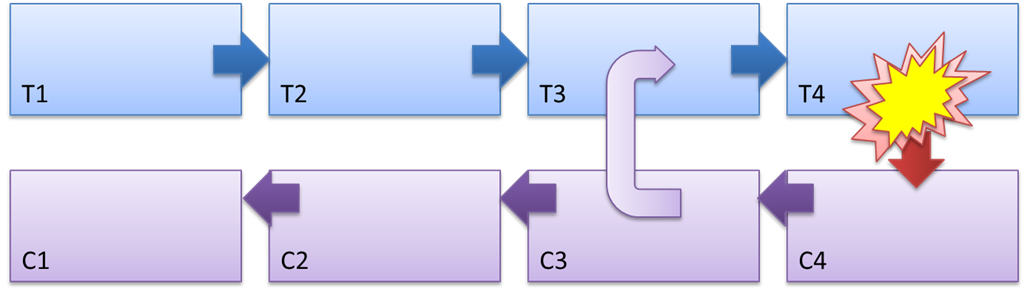

Figure 3 - The mechanism of Saga and the nature of the compensating action

In Figure 3, the saga steps are designated as T1 ... T4, compensating actions: C1 ... C4.

The sagas support the idempotency of the steps (an action whose multiple repetition is equivalent to a single one). The saga approach provides the ability to repeat any step (for example, if you have not received a response on successful completion). Also idempotency allows you to recover from the loss of data on any node (failure and recovery). When executing a step, each service must determine (using the idempotency key) it has already performed this step, or not (if not, perform, otherwise, skip). For compensating actions, it is also possible to add idempotency keys and repetition of operations (ensuring persistence / sustainability).

Summary

Of the four requirements for the ACID transaction system (atomicity, consistency, isolation, stability), the sagas mechanism allows for three - all but isolation. The lack of isolation can lead to anomalies (dirty reads, non-repeatable reads, overwriting changes between different business transactions, etc.). To overcome such situations, it is necessary to use additional mechanisms, for example, the versionality of objects being modified.

The sagas allow to solve the following tasks:

- Provide dependent data changes for business critical data;

- Have the ability to set a strict order of steps;

- Comply with 100% consistency (reconcile data even in case of accidents);

- Provide performance checks at all levels.

Scope and examples of application

Sagas are often used in systems with a large number of requests. For example, popular mail services, social networks. However, the approach can be applied in projects of smaller scale.

Our company has experience in developing an accounting system for a large enterprise, which was designed for several dozen users and all data was stored in one relational DBMS. The problem arose during the implementation of the automatic calculation of the planned work: in some cases, the calculations were very large and required the insertion of millions of records into the DBMS tables, which significantly loaded the DBMS and slowed down the work of the entire system.

A solution was found - to make the logic of calculating the work in a separate service from its separate database management system for storing the work itself and related objects. Data consistency was provided through the saga. If the calculation fails, then the main module of the application received the command to cancel the logical operation of the calculation.

Libraries with Saga support

The application was developed on .Net, and for this technology there are several library service managers with support for sagas. We looked at the NServiceBus, MassTransit, and Rebus libraries. As a result, we stopped at Rebus - this library is easier to learn, while fully implementing the principle of sagas and free to use. NServiceBus and MassTransit are more sophisticated tools with a ton of extra features. As part of our task, they were not required, but it may be advisable to use them in future projects with more complex logic.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/431854/

All Articles