Information security of the Internet of things: who is the thing and who is the owner?

A source

It's no secret that in the field of the Internet of Things (Internet of Things, IoT), perhaps the least order in terms of information security (IB). Today we are witnessing a developing technology, a constantly changing landscape of the industry, forecasts, sometimes leading away from reality, dozens of organizations trying to declare themselves legislators in a particular area, even for an hour. The urgency of the problem is emphasized by epic incidents. Industroyer, BrickerBot, Mirai - and this is only the tip of the iceberg, and what is the next day preparing for us? If you continue to go with the flow, then the owners of the Internet of things will be botnets and other "malware." And things with ill-conceived functional will prevail over those who try to become their master.

In November 2018, ENISA (The European Union Agency for Networks and Information Security) released a document entitled “ Cybersecurity Practices for the Industrial Internet of Things”, which analyzed about a hundred documents with best practices in this area. What is "under the hood" of this attempt to grasp the immense? The article provides an overview of the content.

Industrial Internet of Things (Industrial Internet of Things, IIoT), which includes, among other things, objects of critical information infrastructure (CII), stands somewhat apart from the classic IoT. Operators IIoT systems are accustomed to implement fairly mature technical solutions with a horizon of operation in decades. Thus, the introduction of upgrades and innovations using IIoT solutions is hampered by the dynamism of the market with the absence of a generally accepted system of standards and generally accepted licensing schemes.

')

Another question: what to do with the sea of information accumulated in the field of information security IoT for the last 3-4 years? What should be taken as a basis, and what is secondary? And if in different documents there is conflicting information, what is more important? One of the answers may be the study of analytical reports, which summarize and harmonize the accumulated experience, taking into account the maximum number of available sources.

So ENISA offers a summary of experience based on the use of best practices. To demonstrate that this approach is not the only one, consider another possibility, namely, the creation of a collection of various standards.

The Draft NISTIR 8200 document can be found on the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) website. International Cybersecurity Standardization for Internet of Things (IoT) . The version is dated February 2018, and while it still has the status of a draft. It analyzes existing standards, distributed in the following 11 areas: Cryptographic Techniques, Cyber Incident Management, Hardware Assurance, Identity and Access Management, Information Security Management Systems (ISMS), IT System Security Evaluation, Network Security, Security Automation and Continuous Monitoring (SACM) ), Software Assurance, Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM), System Security Engineering.

The list of standards takes more than one hundred pages! It means that there are hundreds of titles there, they are tens of thousands of pages, the study of which can take years, moreover, many documents are paid. This identified multiple gaps in the standardization of the industry, which, obviously, will be filled.

I think the reader has already understood what approach the author’s common sense and sympathies are on. Therefore, let us return to the best practices of ENISA. They are based on an analysis of about a hundred documents already released. However, we do not need to read all these documents, since ENISA experts have already collected all the most important things in their report.

The figure below shows the structure of the document, and we will now take a closer look at it.

Figure 1: The structure of the document on the subject of Smart Manufacturing

The first part is introductory.

The second part first introduces the basic terminology (2.1), and then the security calls (2.2), which include:

- Vulnerable components

- deficiencies in process management (Management of processes);

- increasing number of communication links (Increased connectivity);

- interaction of operational and information technologies (IT / OT convergence);

- inheritance of problems of industrial control systems (Legacy industrial control systems);

- Insecure protocols;

- human factors;

- excessive functionality (Unused functionalities);

- the need to consider aspects of functional safety (Safety aspects);

- implementation of updates related to Security;

- Realization of the life cycle of information security (Secure product lifecycle).

In section 2.3, with reference to ISA, the reference architecture is given, which, nevertheless, somewhat contradicts the generally accepted architecture of the ISA (Purdu), since the RTU and PLC are assigned to the 2nd, and not to the 1st level (as it is practiced in ISA).

Figure 2. IIoT Reference Architecture

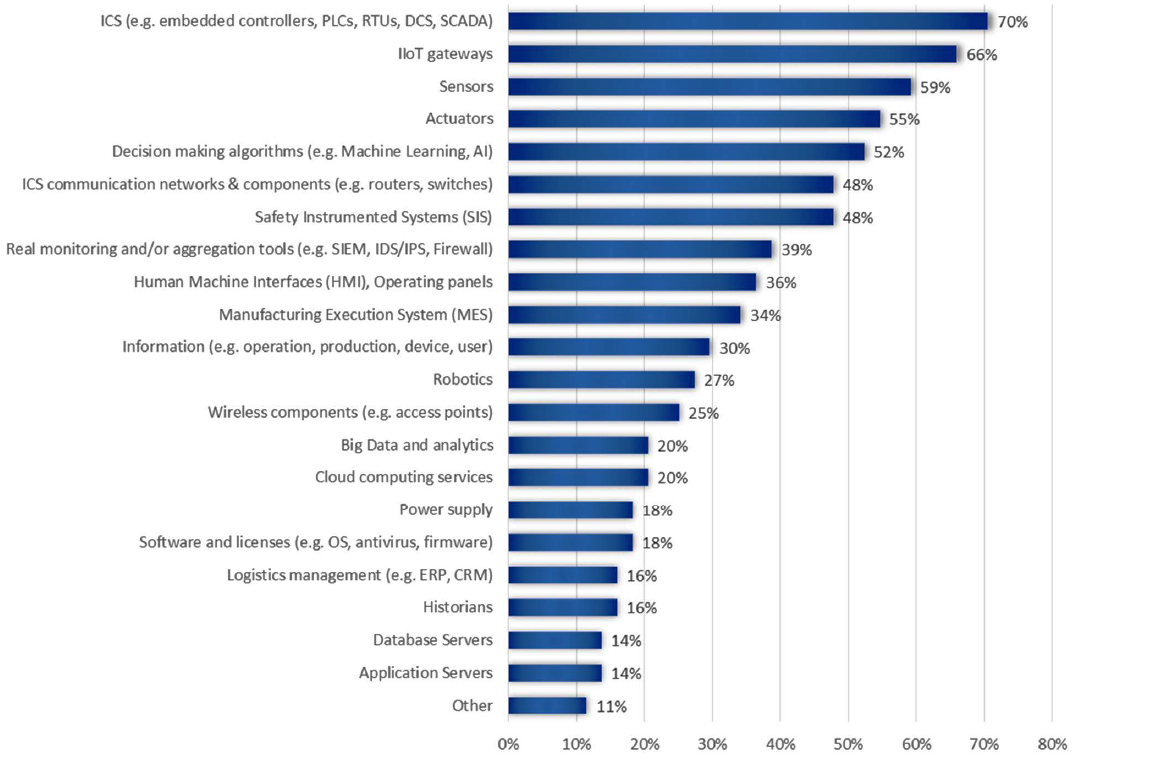

The reference architecture is an input for the formation of a taxonomy of assets, which is done in section 2.4. Based on expert data, the criticality of assets in terms of their impact on information security is evaluated. We are not talking about representativeness (the report says that experts from 42 different organizations participated), and you can take this statistics as “some opinion”. Percentages in the chart indicate the percentage of experts who rated an asset as the most critical.

Figure 3. The results of expert assessment of the criticality of assets IIoT

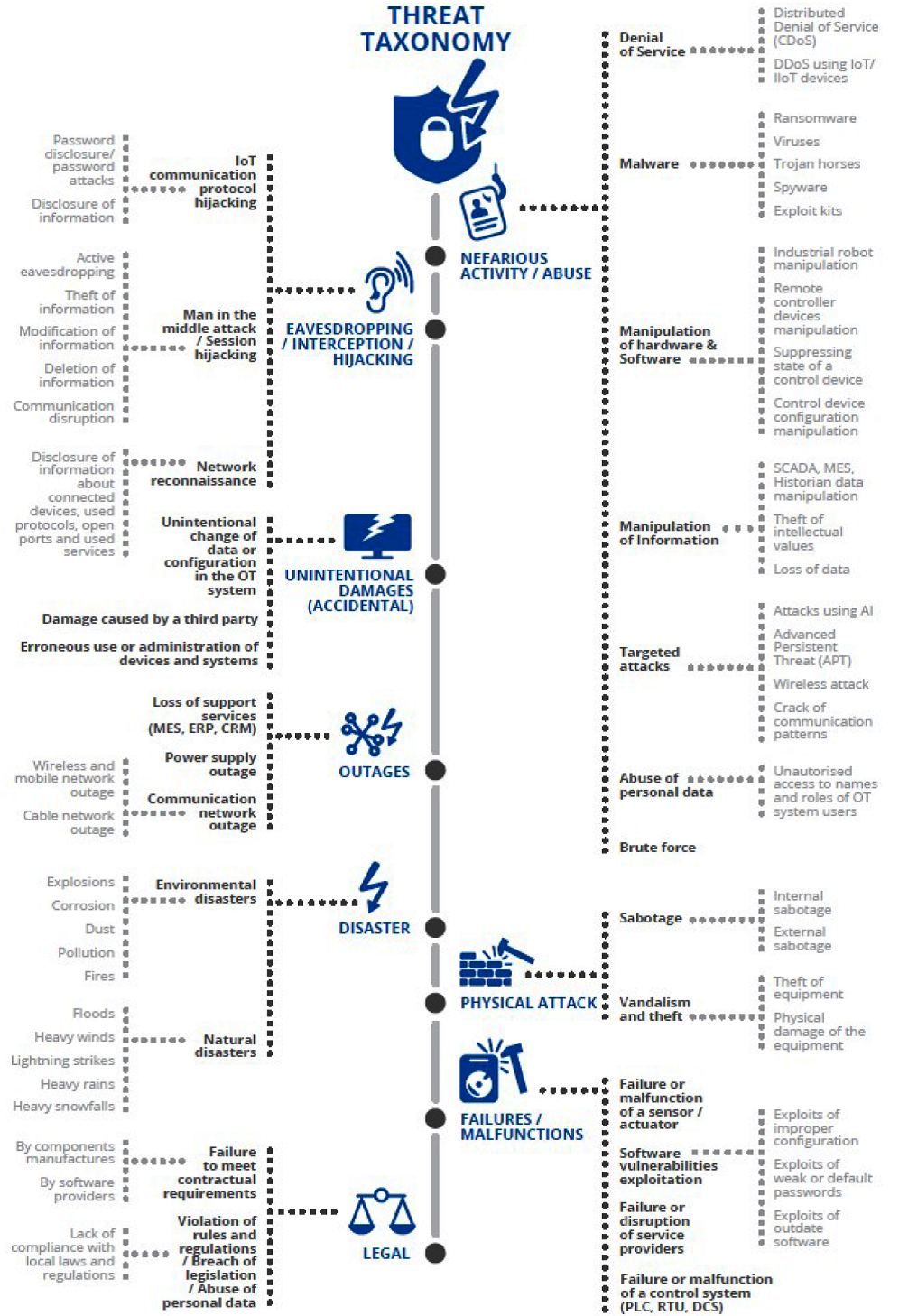

Section 3.1 describes the classification and description of potential threats as applied to the IIoT area. In addition, asset classes that may be affected are associated with each threat. The main classes of threats are highlighted:

- Nefarious activity / Abuse (unfair activities and abuses) - various kinds of manipulations with data and devices;

- Eavesdropping / Interception / Hijacking (listening / intercepting / hacking) - collecting information and hacking the system;

- Unintentional damages (accidental) - unintended configuration, administration, and application errors;

- Outages (outages) - interruptions in work associated with the loss of power supply, communications or services;

- Disaster (catastrophes) - destructive external impacts of natural and man-made character;

- Physical attack (physical attacks) - theft, vandalism and sabotage (disabling), performed directly on the equipment;

- Failures / Malfunctions (failures and malfunctions) - can occur due to accidental hardware failures, due to provider service failures, and also due to problems in software development, leading to the introduction of vulnerabilities;

- Legal (legal issues) - deviations from the requirements of laws and contracts.

Figure 3. Threat Taxonomy

Section 3.2 discusses typical examples of attacks on the components of IIoT systems.

The most important section in the document is the 4th, which discusses the best practices aimed at protecting the IIoT components. Practices include three categories: policies, organizational practices, and technical practices.

Figure 4. The structure of the best practices of providing information security IIoT

The fundamental difference between policies and organizational practices is not explained, and the procedural level is present in both cases. For example, Risk and Threat Management fell into politics, and Vulnerability Management into organizational practices. The only difference that can be caught is that the policies are applied, first of all, for developers, and organizational practices - for operating organizations.

The composition of policies (4.2) describes 4 categories and 24 practices. The organizational section (4.3) describes 27 practices, divided into 6 categories, and the technical (4.4) - 59 practices, divided into 10 categories.

In Appendix A, it is noted that this document ENISA continues the research declared in 2017 in the document "Baseline Security Recommendations for IoT in the context of Critical Information Infrastructure" . Of course, IoT is a broader concept than IIoT, and, from this point of view, it would be possible to take last year’s document as the basis of this review, however, you always want to deal with newer material.

Appendix B - this is the main semantic part of the document. The list of practices from Section 4 is presented in the form of tables, where a link is made to groups of threats and references are given to documents supporting the use of a particular practice, alas, unfortunately, without specifying a specific page or paragraph. For example, here are a few items related to the security of cloud services.

Figure 5. A fragment of the description of the best practices of providing information security IIoT

Appendix C provides a list of cited documents (there are about 100 of them), which were developed and formed the basis of the best practices developed.

Appendix D lists the most significant incidents related to information security breaches in industrial applications.

findings

“Good Practices for Internet Security of Things” , developed in November 2018, is by far one of the most detailed documents in the field of information security of the Internet of Things. There is no detailed technical information on the implementation of 110 described practices, however, there is a body of accumulated knowledge obtained from the analysis of hundreds of documents from leading expert organizations in the field of IoT.

The document focuses on IIoT, takes into account the industrial architecture and associated with it, assets, threats and scenarios of possible attacks. More common for IoT is the ENISA predecessor document Baseline Security Recommendations for IoT in the context of Critical Information Infrastructures , released in 2017.

The “predatory things of the century” and the inconspicuous tendency for us to gain the power of things over people are being held back at the moment only by a scattered resistance to measures to ensure information security. On how effective the IS measures will be, in many ways, our future depends.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/430822/

All Articles