JavaScript Guide, Part 3: Variables, Data Types, Expressions, Objects

Today, in the third part of the translation of the JavaScript guide, we will talk about different ways of declaring variables, data types, expressions, and features of working with objects.

→ Part 1: first program, language features, standards

→ Part 2: code style and program structure

→ Part 3: Variables, Data Types, Expressions, Objects

→ Part 4: Functions

→ Part 5: Arrays and Loops

→ Part 6: Exceptions, Semicolon, Pattern Literals

→ Part 7: strict mode, this keyword, events, modules, mathematical calculations

→ Part 8: ES6 feature overview

→ Part 9: Overview of ES7, ES8, and ES9 Capabilities

A variable is an identifier that has been assigned a value. The variable can be accessed in the program, working in this way with the value assigned to it.

')

By itself, a variable in JavaScript does not contain information about the type of values that will be stored in it. This means that by writing a variable, for example, a string, you can later write a number into it. Such an operation will not cause an error in the program. That is why JavaScript is sometimes called "untyped" language.

Before using a variable, it must be declared using the

Prior to the ES2015 standard, using the

If you omit

So, if the so-called strict mode (strict mode) is included, the similar will cause an error. If strict mode is not enabled, an implicit variable declaration will occur and it will be assigned to the global object. In particular, this means that a variable implicitly declared in this way in a certain function will be available after the function completes. Usually, it is expected that variables declared in functions do not “go beyond” their limits. It looks like this:

The console will get

For example, it may look like this:

If, when a variable is declared, it is not initialized, it is not assigned any value to it, it will automatically be assigned the value

Variables declared with the

You can declare several variables in one expression:

The scope of a variable (scope) is the area of the program in which this variable is available (visible).

A variable initialized with the

If in the function, using

It is important to understand that blocks (code areas enclosed in braces) do not create new scopes. A new scope is created when the function is called. The

If a variable is declared in the function code, it is visible to the entire function code. Even if a variable is declared using

The let keyword appeared in ES2015, which, simply, can be called the “block” version of

If the word “let” itself does not seem very clear, one can imagine that the word “let” is used instead. Then the expression

When using the

For example, this code will cause an error:

If, at the initialization of the cycle, the counter

Nowadays, when developing JS programs based on modern standards, it is possible to completely abandon

Values of variables declared using the

In this example, the constant

When they say that an object is written to a variable, they actually mean that an object reference is stored in the variable. This link cannot be changed, and the object to which the link leads can be changed.

The

In the

The

In modern conditions, it is quite possible to use to declare all entities whose values are not planned to change, the keyword

JavaScript is sometimes called "untyped" language, but this does not correspond to the real state of affairs. True, you can write values of different types to variables, but there are data types in JavaScript, after all. In particular, we are talking about primitive and object data types.

In order to determine the data type of a certain value, you can use the

Here is a list of primitive JavaScript data types:

Here, the data type names are given in the form in which the

Let's talk about the most commonly used data types from this list.

Values of type

In the code, numeric literals are represented as integers and fractional numbers in the decimal number system. To write numbers you can use other methods. For example, if at the beginning of a numeric literal there is a prefix

Here are examples of writing integers:

Here are fractional numbers.

Numeric literals (this behavior is also characteristic of some other primitive types), when attempting to refer to them as objects, automatically, for the duration of the operation, are transformed into corresponding objects, which are called “object wrappers”. In this case, we are talking about the object wrapper

Here, for example, looks like an attempt to access the variable

Number Object Wrap Tips

If, for example, you use the

Notice the double brackets after the method name. If you do not put them, the system will not give an error, but, instead of the expected output, the console will be something that does not look like the string representation of the number 5

The global

Values of type

String values can be broken down into multiple parts using the backslash (backslash) character.

A string can contain so-called escape sequences interpreted when a string is output to the console. For example, the sequence

Strings can be concatenated using the

In ES2015, the so-called patterned literals, or patterned strings, appeared. They are strings enclosed in backquotes (

For example, you can substitute certain values in template literals that are the result of evaluating JavaScript expressions.

Using back quotes simplifies multi-line writing of string literals:

In JavaScript, there are a couple of reserved words used when working with logical values — this is

Logical expressions are used in constructions like

It should be noted that where

In particular, the false values are the following:

The remaining values are true.

JavaScript has a special

The value

This value is automatically returned from functions whose result is not explicitly returned, using the keyword

In order to check the value for

All values that are not primitive have an object type. We are talking about functions, arrays, what we call "objects", and many other entities. All of these data types are based on the

Expressions are fragments of code that can be processed and obtained on the basis of the performed calculations a certain value. There are several categories of expressions in JavaScript.

Expressions fall into this category, the result of which are the numbers.

The result of evaluating such expressions is strings.

Literals, constants, references to identifiers fall into this category.

This also includes some key words and JavaScript constructs.

In logical expressions, logical operators are used, the result of their calculation is logical values.

These expressions allow you to access the properties and methods of objects.

Such expressions are used to call functions or methods of objects.

Above, we have already encountered objects, talking about object literals, calling their methods, accessing their properties. Here we will talk about objects in more detail, in particular, we will consider the mechanism of prototype inheritance and the use of the

JavaScript stands out among modern programming languages in that it supports prototype inheritance. Most object-oriented languages use a class-based inheritance model.

Each JavaScript object has a special property (

Suppose we have an object created using an object literal.

Or we created an object using the

In any of these cases, the prototype of the

If you create an array that is also an object, its prototype will be an

You can check this as follows.

Here we used the

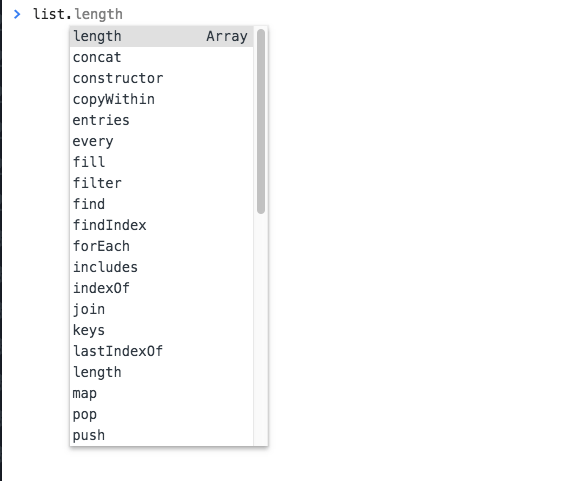

All properties and methods of the prototype are available to the object that has this prototype. Here, for example, how their list for an array looks.

Array hint

The basic prototype for all objects is the

What we saw above is an example of a chain of prototypes.

When trying to access a property or a method of an object, if there is no such property or method of the object itself, they are searched in its prototype, then in the prototype prototype, and so on until the required one is found, or until the prototype chain is not over.

In addition to creating objects using the

You can check if a certain object is in the prototype chain of another object using the

Above, we created new objects using the constructor functions already existing in the language (when they are called, the

-. ,

,

ES6 JavaScript «».

JavaScript . , JS . , , , « » . , , , , , .

.

,

.

. , , , , .

, ( ) , , -, .

(), .

, , , , , . (

JavaScript , (, ) . , , .

,

, , JavaScript. .

Dear readers! JS, , class.

→ Part 1: first program, language features, standards

→ Part 2: code style and program structure

→ Part 3: Variables, Data Types, Expressions, Objects

→ Part 4: Functions

→ Part 5: Arrays and Loops

→ Part 6: Exceptions, Semicolon, Pattern Literals

→ Part 7: strict mode, this keyword, events, modules, mathematical calculations

→ Part 8: ES6 feature overview

→ Part 9: Overview of ES7, ES8, and ES9 Capabilities

Variables

A variable is an identifier that has been assigned a value. The variable can be accessed in the program, working in this way with the value assigned to it.

')

By itself, a variable in JavaScript does not contain information about the type of values that will be stored in it. This means that by writing a variable, for example, a string, you can later write a number into it. Such an operation will not cause an error in the program. That is why JavaScript is sometimes called "untyped" language.

Before using a variable, it must be declared using the

var or let keyword. If we are talking about a constant, the keyword const . It is possible to declare a variable and assign it some value without using these keywords, but this is not recommended.Var var keyword

Prior to the ES2015 standard, using the

var keyword was the only way to declare variables. var a = 0 If you omit

var in this construct, then the value will be assigned to an undeclared variable. The result of this operation depends on the mode in which the program runs.So, if the so-called strict mode (strict mode) is included, the similar will cause an error. If strict mode is not enabled, an implicit variable declaration will occur and it will be assigned to the global object. In particular, this means that a variable implicitly declared in this way in a certain function will be available after the function completes. Usually, it is expected that variables declared in functions do not “go beyond” their limits. It looks like this:

function notVar() { bNotVar = 1 // } notVar() console.log(bNotVar) The console will get

1 , usually no one expects such behavior from the program, the expression bNotVar = 1 does not look like an attempt to declare and initialize a variable, but as an attempt to access a variable that is external to the function (this is quite normal). As a result, the implicit declaration of variables confuses those who read the code and can lead to unexpected program behavior. Later we will talk about functions and areas of visibility, but in the meantime try to always, when the meaning of a certain expression is to declare a variable, to use specialized keywords. If in this example the function body is rewritten as var bNotVar = 1 , then an attempt to launch the above code snippet will result in an error message (you can see it in the browser console).For example, it may look like this:

Uncaught ReferenceError: bNotVar is not defined . Its meaning is that the program cannot work with a non-existent variable. It is much better, when you first start the program, to see such an error message than to write incomprehensible code that is able to behave unexpectedly.If, when a variable is declared, it is not initialized, it is not assigned any value to it, it will automatically be assigned the value

undefined . var a //typeof a === 'undefined' Variables declared with the

var keyword can be repeatedly declared again by assigning new values to them (but this can confuse the person who is reading the code). var a = 1 var a = 2 You can declare several variables in one expression:

var a = 1, b = 2 The scope of a variable (scope) is the area of the program in which this variable is available (visible).

A variable initialized with the

var keyword outside of a function is assigned to a global object. It has a global scope and is accessible from anywhere in the program. If a variable is declared using the var keyword inside a function, then it is visible only inside this function, being a local variable for it.If in the function, using

var , a variable is declared, the name of which coincides with the name of a variable from the global scope, it will “overlap” the global variable. That is, when accessing such a variable inside a function, its local variant will be used.It is important to understand that blocks (code areas enclosed in braces) do not create new scopes. A new scope is created when the function is called. The

var keyword has a so-called functional scope, not a block scope.If a variable is declared in the function code, it is visible to the entire function code. Even if a variable is declared using

var at the end of the function code, it can also be accessed at the beginning of the code, since the JavaScript variable lifting mechanism (hoisting) works. This mechanism "raises" the declaration of variables, but not the operation of their initialization. This can be a source of confusion, so make it a rule to declare variables at the beginning of a function.Let Keyword let

The let keyword appeared in ES2015, which, simply, can be called the “block” version of

var . The scope of variables declared using the let keyword is limited to the block, statement, or expression in which it is declared, as well as nested blocks.If the word “let” itself does not seem very clear, one can imagine that the word “let” is used instead. Then the expression

let color = 'red' can be translated into English like this: “let the color be red”, and into Russian like this: “let the color be red”.When using the

let keyword, you can get rid of the ambiguities that accompany the var keyword (for example, you won’t be able to declare the same variable twice using let ). Using let outside of a function, say, when initializing loops, does not create global variables.For example, this code will cause an error:

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) { console.log(i) } console.log(i) If, at the initialization of the cycle, the counter

i will be declared using the var keyword, then i will be available outside the cycle, after it finishes its work.Nowadays, when developing JS programs based on modern standards, it is possible to completely abandon

var and use only the keywords let and const .▍ Keyword const

Values of variables declared using the

var or let keywords can be overwritten. If instead of these keywords const used, then a new value cannot be assigned to a constant declared and initialized with its help. const a = 'test' In this example, the constant

a cannot assign a new value. But it should be noted that if a is not a primitive value, like a number, but an object, using the keyword const does not protect this object from changes.When they say that an object is written to a variable, they actually mean that an object reference is stored in the variable. This link cannot be changed, and the object to which the link leads can be changed.

The

const keyword does not make objects immutable. It simply protects against changes references to them, written in the corresponding constants. Here's what it looks like: const obj = {} console.log(obj.a) obj.a = 1 // console.log(obj.a) //obj = 5 // In the

obj constant, at initialization, a new empty object is written. Attempting to access its a property, a non-existent, does not cause an error. The console gets undefined . After that we add a new property to the object and try to access it again. This time, the value of this property is set to the console - 1 . If you uncomment the last line of the example, an attempt to execute this code will result in an error.The

const keyword is very similar to let , in particular, it has a block scope.In modern conditions, it is quite possible to use to declare all entities whose values are not planned to change, the keyword

const , resorting to let only in special cases. Why? The thing is that it is best to strive to use the simplest available designs as possible in order not to complicate the program and avoid mistakes.Data types

JavaScript is sometimes called "untyped" language, but this does not correspond to the real state of affairs. True, you can write values of different types to variables, but there are data types in JavaScript, after all. In particular, we are talking about primitive and object data types.

In order to determine the data type of a certain value, you can use the

typeof operator. It returns a string indicating the type of the operand.Primitive data types

Here is a list of primitive JavaScript data types:

numberstring(string)boolean(boolean)null(special valuenull)undefined(special valueundefined)symbol(symbol, used in special cases, appeared in ES6)

Here, the data type names are given in the form in which the

typeof operator returns them.Let's talk about the most commonly used data types from this list.

Type number

Values of type

number in JavaScript are represented as 64-bit double-precision floating-point numbers.In the code, numeric literals are represented as integers and fractional numbers in the decimal number system. To write numbers you can use other methods. For example, if at the beginning of a numeric literal there is a prefix

0x - it is perceived as a number written in hexadecimal notation. Numbers can be written in the exponential representation (in such numbers you can find the letter e ).Here are examples of writing integers:

10 5354576767321 0xCC // Here are fractional numbers.

3.14 .1234 5.2e4 //5.2 * 10^4 Numeric literals (this behavior is also characteristic of some other primitive types), when attempting to refer to them as objects, automatically, for the duration of the operation, are transformed into corresponding objects, which are called “object wrappers”. In this case, we are talking about the object wrapper

Number .Here, for example, looks like an attempt to access the variable

a , in which a numeric literal is written, as an object, in the Google Chrome console.

Number Object Wrap Tips

If, for example, you use the

toString() method of an object of type Number , it will return a string representation of the number. The corresponding command that can be executed in the browser console (and in the usual code) looks like this: a.toString() Notice the double brackets after the method name. If you do not put them, the system will not give an error, but, instead of the expected output, the console will be something that does not look like the string representation of the number 5

The global

Number object can be used as a constructor, creating new numbers with it (although it is almost never used in this form), it can also be used as an independent entity without creating its instances (that is, certain numbers represented from its using). For example, its Number.MAX_VALUE property contains the maximum numeric value that can be represented in JavaScript.Type string

Values of type

string are sequences of characters. Such values are specified as string literals enclosed in single or double quotes. 'A string' "Another string" String values can be broken down into multiple parts using the backslash (backslash) character.

"A \ string" A string can contain so-called escape sequences interpreted when a string is output to the console. For example, the sequence

\n means a newline character. The backslash character can also be used to add quotes to strings enclosed in the same quotes. Escaping the quotation character with \ causes the system not to perceive it as a special character. 'I\'ma developer' Strings can be concatenated using the

+ operator. "A " + "string" Pattern Literals

In ES2015, the so-called patterned literals, or patterned strings, appeared. They are strings enclosed in backquotes (

` ) and have some interesting properties. `a string` For example, you can substitute certain values in template literals that are the result of evaluating JavaScript expressions.

`a string with ${something}` `a string with ${something+somethingElse}` `a string with ${obj.something()}` Using back quotes simplifies multi-line writing of string literals:

`a string with ${something}` Type boolean

In JavaScript, there are a couple of reserved words used when working with logical values — this is

true (true) and false (false). Comparison operations, such as == , === , < , > , return true or false .Logical expressions are used in constructions like

if and while , helping to control the program flow.It should be noted that where

true or false is expected, other values can be used that are automatically regarded by the language as true (truthy) or false (falsy).In particular, the false values are the following:

0 -0 NaN undefined null '' // The remaining values are true.

Type null

JavaScript has a special

null value that indicates the absence of a value. Similar values are used in other languages.Type undefined

The value

undefined written to a variable indicates that the variable is not initialized and has no value for it.This value is automatically returned from functions whose result is not explicitly returned, using the keyword

return . If the function accepts a certain parameter that, when called, is not specified, it is also set to undefined .In order to check the value for

undefined , you can use the following construction. typeof variable === 'undefined' ▍Objects

All values that are not primitive have an object type. We are talking about functions, arrays, what we call "objects", and many other entities. All of these data types are based on the

object type, and they, although in many ways different from each other, have much in common.Expressions

Expressions are fragments of code that can be processed and obtained on the basis of the performed calculations a certain value. There are several categories of expressions in JavaScript.

Arithmetic expressions

Expressions fall into this category, the result of which are the numbers.

1 / 2 i++ i -= 2 i * 2 String expressions

The result of evaluating such expressions is strings.

'A ' + 'string' 'A ' += 'string' Primary expressions

Literals, constants, references to identifiers fall into this category.

2 0.02 'something' true false this // , undefined i // i This also includes some key words and JavaScript constructs.

function class function* // yield // / yield* // async function* // await // /pattern/i // () // Array and Object Initialization Expressions

[] // {} // [1,2,3] {a: 1, b: 2} {a: {b: 1}} Boolean expressions

In logical expressions, logical operators are used, the result of their calculation is logical values.

a && b a || b !a Property Access Expressions

These expressions allow you to access the properties and methods of objects.

object.property // ( ) object[property] object['property'] Object creation expressions

new object() new a(1) new MyRectangle('name', 2, {a: 4}) Function Declaration Expressions

function() {} function(a, b) { return a * b } (a, b) => a * b a => a * 2 () => { return 2 } Call expressions

Such expressions are used to call functions or methods of objects.

ax(2) window.resize() Work with objects

Above, we have already encountered objects, talking about object literals, calling their methods, accessing their properties. Here we will talk about objects in more detail, in particular, we will consider the mechanism of prototype inheritance and the use of the

class keyword.Prototype inheritance

JavaScript stands out among modern programming languages in that it supports prototype inheritance. Most object-oriented languages use a class-based inheritance model.

Each JavaScript object has a special property (

__proto__ ), which points to another object that is its prototype. The object inherits the properties and methods of the prototype.Suppose we have an object created using an object literal.

const car = {} Or we created an object using the

Object constructor. const car = new Object() In any of these cases, the prototype of the

car object is the Object.prototype .If you create an array that is also an object, its prototype will be an

Array.prototype object. const list = [] // const list = new Array() You can check this as follows.

car.__proto__ == Object.prototype //true car.__proto__ == new Object().__proto__ //true list.__proto__ == Object.prototype //false list.__proto__ == Array.prototype //true list.__proto__ == new Array().__proto__ //true Here we used the

__proto__ property, it does not have to be available to the developer, but you can usually access it. It should be noted that a more reliable way to get a prototype of an object is to use the getPrototypeOf() method of the global Object . Object.getPrototypeOf(new Object()) All properties and methods of the prototype are available to the object that has this prototype. Here, for example, how their list for an array looks.

Array hint

The basic prototype for all objects is the

Object.prototype . Array.prototype.__proto__ == Object.prototype Object.prototype no prototype.What we saw above is an example of a chain of prototypes.

When trying to access a property or a method of an object, if there is no such property or method of the object itself, they are searched in its prototype, then in the prototype prototype, and so on until the required one is found, or until the prototype chain is not over.

In addition to creating objects using the

new operator and applying object literals or array literals, you can create an instance of an object using the Object.create() method. The first argument passed to this method is the object that will become the prototype of the object created with it. const car = Object.create(Object.prototype) You can check if a certain object is in the prototype chain of another object using the

isPrototypeOf() method. const list = [] Array.prototype.isPrototypeOf(list) Constructor functions

Above, we created new objects using the constructor functions already existing in the language (when they are called, the

new keyword is used). . . function Person(name) { this.name = name } Person.prototype.hello = function() { console.log(this.name) } let person = new Person('Flavio') person.hello() console.log(Person.prototype.isPrototypeOf(person)) -. ,

this . name , . . - , name , .,

name , . , , , hello() . , Person hello() ( ).▍

ES6 JavaScript «».

JavaScript . , JS . , , , « » . , , , , , .

.

class Person { constructor(name) { this.name = name } hello() { return 'Hello, I am ' + this.name + '.' } } ,

new ClassIdentifier() .constructor , ..

hello() — , , . Person . const flavio = new Person('Flavio') flavio.hello() ,

. , , , , .

, ( ) , , -, .

class Programmer extends Person { hello() { return super.hello() + ' I am a programmer.' } } const flavio = new Programmer('Flavio') flavio.hello() hello() Hello, I am Flavio. I am a programmer .(), .

super ., , , , , . (

static ) , .JavaScript , (, ) . , , .

,

get set . — , , . -, — . class Person { constructor(name) { this.userName = name } set name(value) { this.userName = value } get name() { return this.userName } } Results

, , JavaScript. .

Dear readers! JS, , class.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/429838/

All Articles