Wrong, wrong, WRONG! methods of DDoS mitigation

Habr, this is a transcription of a CTO Qrator Labs performance by Tyoma ximaera Gavrichenkov on RIPE77 in Amsterdam. We could not translate its name into Russian with preservation of meaning, and therefore we decided to assist Habra in entering the English-language market and left everything as is

This is a quote from one of my favorite bands. Dave Gahan of Depeche Mode is a living proof that you can say the word “wrong” 65 times in 5 minutes and still remain a rock star. Let's see if I can do it.

Do you know that people simply adore geography?

')

All these, you know, trendy maps and architectural plans.

Perhaps this is the main reason why, while reading the StackExchange security section , I constantly stumble upon the same approach to preventing cyber attacks.

Suppose we, as a company, do not expect the Spanish Inquisition, ugh , Chinese users. Why don't we just restrict access from their IP addresses? We are not Facebook after all, and our services are available only in a limited number of regions. And, actually, Facebook is also unavailable in China, why should we worry?

Outside the world of information technology, this technique is sometimes called redlining . The essence of this phenomenon is as follows.

Suppose you are the director of a taxis or pizzeria. You have accumulated some statistics that in some areas of the city can rob your courier, or there is a high probability that your car will be scratched. Well, you collect all the employees, draw a thick red line on the map of the city and announce that you do not provide services beyond the red border. (Due to the nature of the structure of most American cities, this, by the way, is almost equivalent to a denial of services on an ethnic basis and is considered a big problem.)

We can do the same with IP addresses, right? Any IP address belongs to a country; therefore, there is an official database maintained by the IETF and RIPE, confirming the allocation of each IP address.

Wrong!

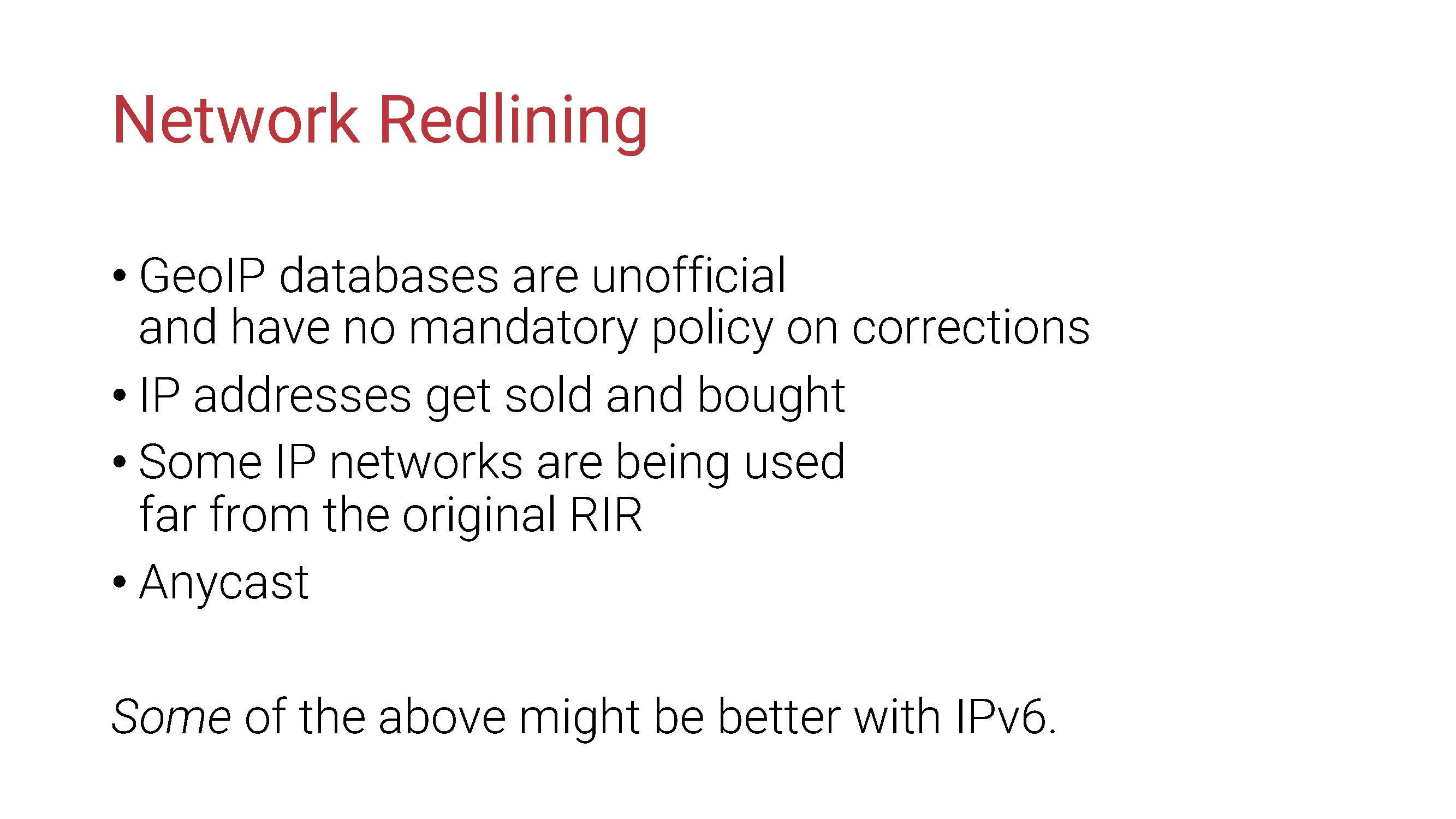

If we confine ourselves only to technical aspects, then, for the time being, the first that comes to mind is the fact that the geo-databases are commercial products of commercial companies, each of which collects data in its own, often not completely clear, ways. Such products can be used for statistical or other research, but providing a wide audience for a production-service based on such a product is an absolute idiocy for countless reasons.

The concept of "belonging" to an IP address does not exist at all. The IP address is not a phone number, the regional registrar does not transfer them to the property, which is explicitly written in its policies. If there is an entity in the world that owns IP addresses, it is IANA , not a country or a company.

As a side note, the process of protecting (your) copyright has just become more complicated at times.

Of course, some of this (although not all) can get better with the advent of IPv6. However, we are now talking about DDoS attacks; The era of real IPv6 DDoS has not yet come, and while we gain experience, completely different situations can arise. In general, it is still too early to think about it.

But, going back to DDoS: what if we know for sure that the remote side is doing something clearly malicious?

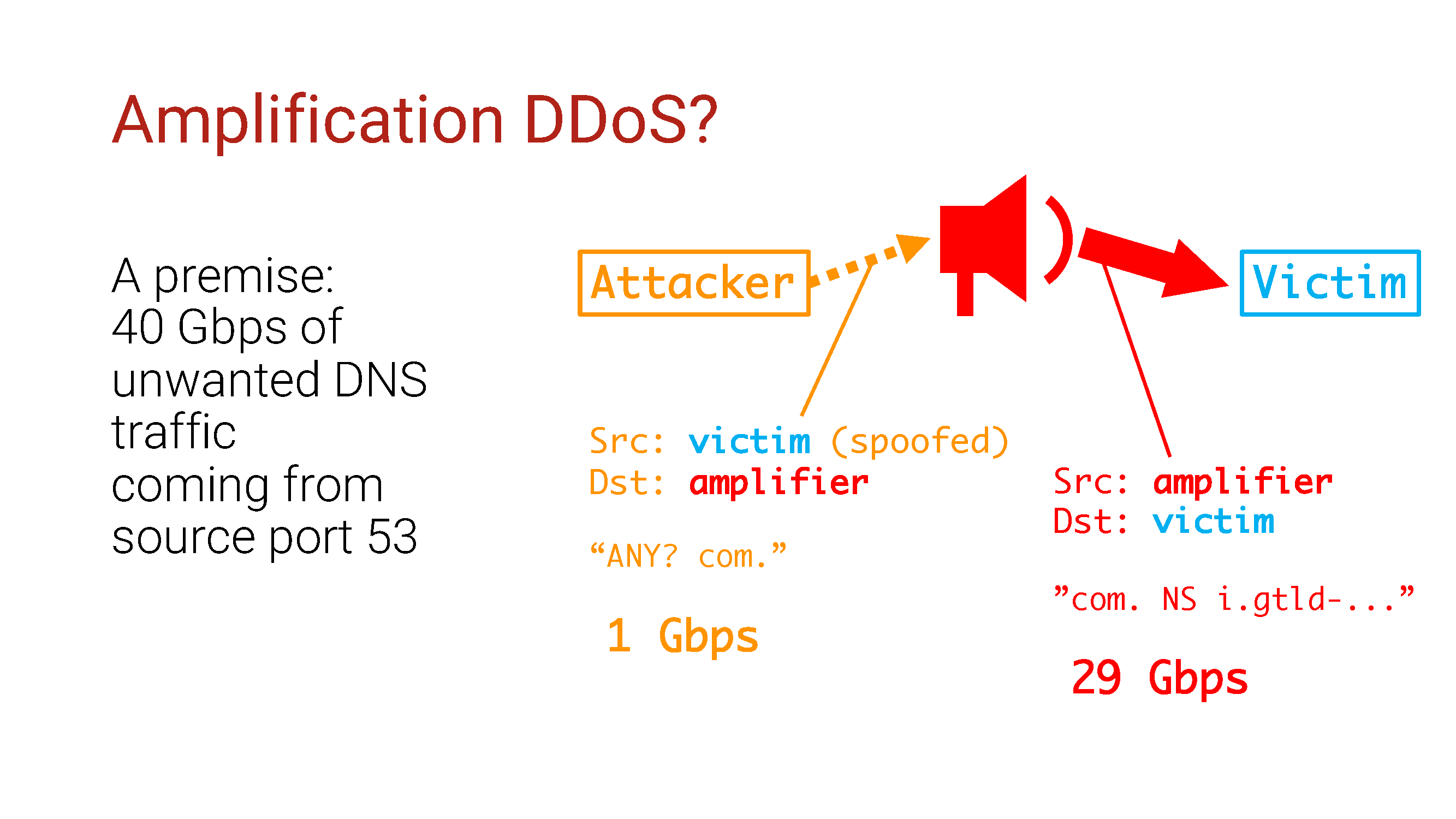

Our setup: 40G traffic, most likely DNS traffic, since it comes from port 53.

As we know, this behavior is typical of attacks such as DNS amplification DDoS. Amplification attacks use a vulnerable server in order to, you know ... increase traffic, and the source IP address in them will be that same vulnerable server.

What if we use any technology we have in order to restrict access to these vulnerable servers? Let all these DNS reflectors be finally patched to stop being a threat, right?

No not like this!

This is a true story. The events described occurred in the state of Minnesota in 1987 . At the request of the survivors, all names have been changed. Out of respect for the dead, the rest of the events were displayed exactly as they occurred.

The company received DNS traffic in the face with gigabytes and decided to deal with them using black lists of IP addresses.

After two hours, the attackers somehow noticed this and immediately changed the attack pattern. Their ability to conduct amplification attacks had previously been based on their ability to generate packets with fake source IP addresses, so they continued to do this, but in a slightly different way.

They began to flood the victim directly with UDP traffic from the source port 53 and fake IP addresses from the entire IPv4 address pool. The NetFlow script used by the company decided that the amplification attack was continuing and began to ban sources.

Since you can sort out the entire IPv4 address space in a matter of hours, you guessed it, it took quite a bit of time for the network equipment to run out of memory and turn it off completely.

To exacerbate the situation, the attackers began by sorting out the prefixes of the end users of the most popular and major broadband providers in this country, so the site was unavailable to visitors long before complete denial of service.

A lesson follows from this: do not produce blacklists automatically if you have not verified the IP address of the source of the attack. Especially when dealing with amplification / reflection attacks. They may not seem to be what they really are.

After that, the question remains.

What if we confirm at least the fact that there is indeed a malicious amplifier on the remote resource? Let's scan the Internet and collect IP addresses with all potential amplifiers. Then, if we see any of them in the source field of the packet, we simply block them — they are still amplifiers, right?

Guess what? Not this way!

There are a number of reasons, each of which states that you should never do this. There are millions of potential amplifiers all over the Internet, and it will be extremely easy to fool you by forcing once again to block an excessive number of IP addresses. IPv6 Internet in general is not easy to scan.

But what is really funny here is that in such a situation, the potential of not only false positives, but also false negatives increases. Whereby?

Redlining in other networks!

People hate network scanners. They block them, as their glamorous IDS equipment marks scanners as a direct threat. They block scanners in a million different ways, and an attacker may have access to amplifiers that you can't do anything about. No one will ask in advance how soft and fluffy your scanner is. IDS has no such concept as a “good external scanner” at all.

Here are the key findings:

- Do not attempt to use blacklists without being sure that the remote side is not fake;

- Do not use blacklists where you cannot do this or where there is a better solution;

- Finally, stop breaking the Internet in ways that it is not designed for!

And remember: a difficult decision is usually better than a simple one, because simple solutions, as a rule, have complex consequences.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/427889/

All Articles