License to drive a car, or why applications should be Single-Activity

At AppsConf 2018 , which was held on October 8-9, I gave a presentation on the creation of android applications entirely in one Activity. Although the topic is well-known, there are many prejudices regarding this choice - a crowded room and the number of questions after the presentation is confirmed. In order not to wait for the video, I decided to make an article with a transcript of the speech.

What I will tell you

- Why and why it is necessary to switch to Single-Activity

- A universal approach to solving the problems that you are used to solve on multiple activities

- Examples of standard business tasks

- Narrow places where the code is usually propped up and not done honestly

Why is Single-Activity right?

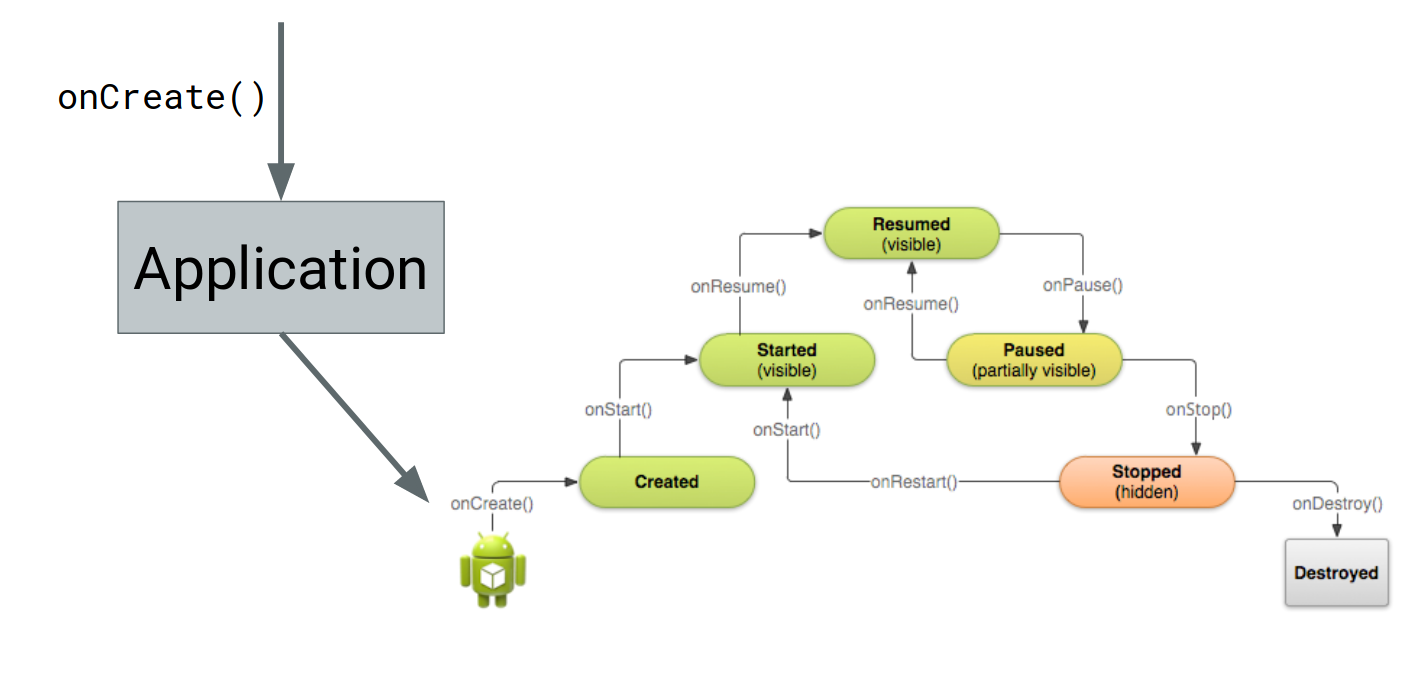

Life cycle

All android developers know the scheme of the "cold" launch of the application. First, onCreate is called on the Application class, then the life cycle of the first Activity comes into effect.

If in our application there are several Activities (and most of such applications), the following occurs:

App.onCreate() ActivityA.onCreate() ActivityA.onStart() ActivityA.onResume() ActivityA.onPause() ActivityB.onCreate() ActivityB.onStart() ActivityB.onResume() ActivityA.onStop() This is the abstract startup log of ActivityB from ActivityA. Empty line - the moment when the launch of the new screen was called. At first glance, everything is fine. But if we turn to the documentation, it becomes clear: to ensure that the screen is visible to the user, and he can interact with it, it is possible only after calling onResume on each screen:

App.onCreate() ActivityA.onCreate() ActivityA.onStart() ActivityA.onResume() <-------- ActivityA.onPause() ActivityB.onCreate() ActivityB.onStart() ActivityB.onResume() <-------- ActivityA.onStop() The problem is that such a log does not help to understand the life cycle of an application. When the user is still inside, and when he has already moved to another application or has turned ours and so on. And this is necessary when we want to bind business logic to the life cycle of an application, for example, keep the socket connection while the user is in the application, and close it when exiting

In the Single-Activity application, everything is simple - the life of the Activity becomes the life of the application. Everything you need for any logic is easy to link to the state of the application.

Running screens

As a user, I often come across the fact that a call from the phone book (and this is clearly the launch of a separate Activity) does not occur after clicking on a contact. It is not clear what this is connected with, but those to whom I tried to get through unsuccessfully said they took the call and heard the sound of footsteps. Moreover, my smartphone has long been in my pocket.

The problem is that launching an Activity is a completely asynchronous process! There is no guarantee of instant launch, and even worse is that we can not control the process. Totally.

In the Single-Activity application, working with the fragment manager, we can control the process.transaction.commit() - performs screen switching asynchronously, which allows you to open or close multiple screens in a row.transaction.commitNow() - switches the screen synchronously, if you do not need to add it to the stack.

fragmentManager.executePendingTransactions () `allows you to perform all previously started transactions right now.

Screen stack analysis

Imagine that the business logic of your application depends on the current depth of the stack of screens (for example, nesting restrictions). Or at the end of some process you need to return to a certain screen, and if there are several identical ones, to the one closest to the root (the beginning of the chain).

How to get an Activity stack? What parameters need to be specified when starting the screen?

By the way, about the magic of startup parameters Activity:

- you can specify the launch flags in Intent (and also mix them with each other, and change them from different places);

- you can add startup parameters in the manifest, because all Activity should be described there;

- add Intent filters here to handle external launch;

- and finally think about MultiTasks, when the Activity can run in different “tasks”.

Taken together, this creates confusion and problems with debugging support. You can never say with certainty exactly how the screen was launched, and how it affected the stack.

In the Single-Activity application, all screens are switched only through fragment transactions. You can analyze the current screen stack and saved transactions.

In the demo application of the Cicerone library, you can see how the current stack status is displayed in the toolbar.

Note: in the latest version of the library support, access to the fragment array inside the fragment manager was closed, but if you really want, this problem can always be solved.

Activity is only one on the screen.

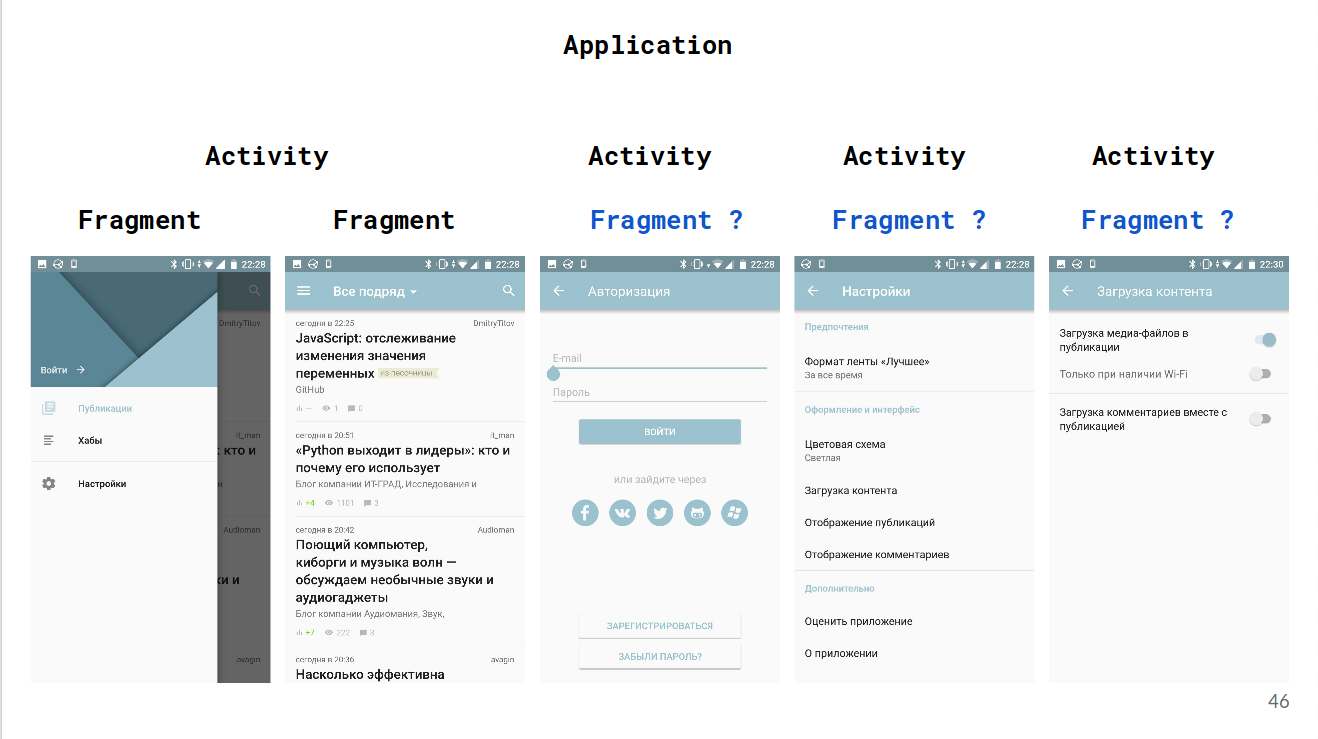

In real applications, we will definitely need to combine the "logical" screens in one Activity, then you cannot write a real application ONLY to the Activity. Duality of approach is always bad, since the same problem can be solved in different ways (somewhere, the layout is right in the Activity, and somewhere, the Activity is just a container).

Don't keep activities

This flag for testing really allows you to find some bugs in the application, but the behavior that it reproduces is NEVER encountered in reality! It does not happen that the application process remains, and at this moment the Activity, even if not active, is dying! An activity can only die with an application process. If the application is displayed to the user, and the system lacks resources, everything around will die (other inactive applications, services, and even a launcher), and your application will live to a victorious end, and if it has to die, then it will be complete.

You can check.

Heritage

Historically, the Activity has a huge amount of superfluous logic, which most likely will not be useful to you. For example, everything you need to work with loaders , actionBar , action menu and so on. This makes the class itself quite massive and ponderous.

Animations

Anyone can make a simple shift animation when switching between activities. Here it is necessary to clarify that we need to make a discount on the asynchronous launch of the Activity, which we talked about earlier.

If you need something more interesting, you can think of such examples of transition animation, which are made on the Activity:

But there is a big problem: it is almost impossible to customize this animation. Designers and the customer is unlikely to please.

With fragments everything is different. We can go straight down to the level of the view hierarchy and make any animation you can imagine! Direct evidence here :

If you look at the source code, you will find that this is done in a conventional layout. Yes, the code is decent there, but animation is always quite difficult, and having this opportunity is always a plus. If you have two Activities switching, then there is no common container in the application where you can make such transitions.

Configuration change on the fly

This point was not in my statement, but it is also very important. If you have a feature with language switching inside the application, then with several Activities it will be quite problematic to implement it, if, among other things, you don’t need to restart the application, but stay in the same place where the user was at the moment of the functionality call.

In the Single-Activity application, it is enough to change the installed locale in the application context and call recreate() on the Activity; the system will do the rest by itself.

At last

Google has a solution for navigation, the documentation of which explicitly states that it is desirable to write a Single-Activity application.

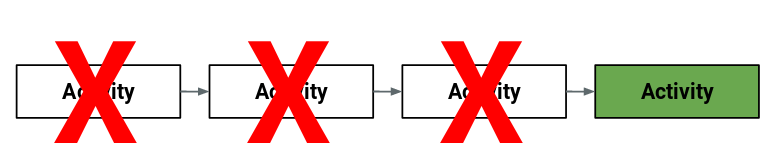

At this point, I hope you have no doubt that the classic approach with several Activities contains a number of drawbacks, which are usually taken as a blind eye, hiding behind the general tendency of Android discontent.

If so, then why is Single-Activity not yet a development standard?

Here I will quote my good friend:

Starting a new serious project, any leader is afraid of failure and avoids risky decisions. It is right. But I will try to provide a comprehensive plan for the transition to Single-Activity.

Transition to Single-Activity

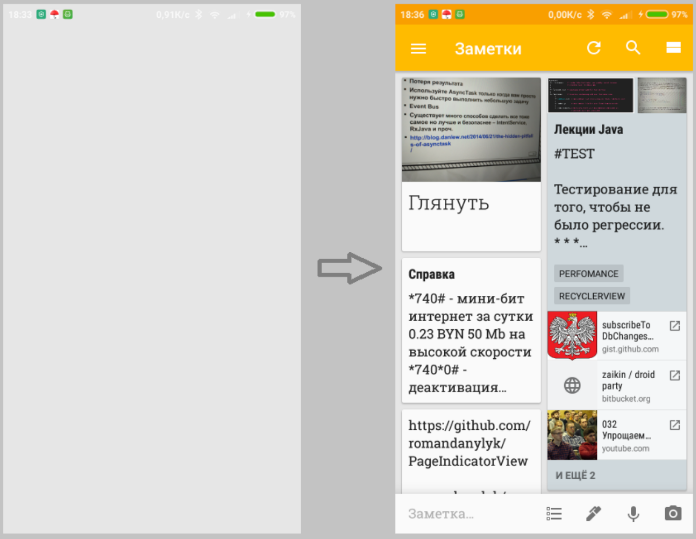

If you study this application, you can determine by its characteristic animations and behavior that it is written in several Activities. I could be wrong, and everything was done even on custom views, but this will not affect our reasoning.

And now attention! Do this like this:

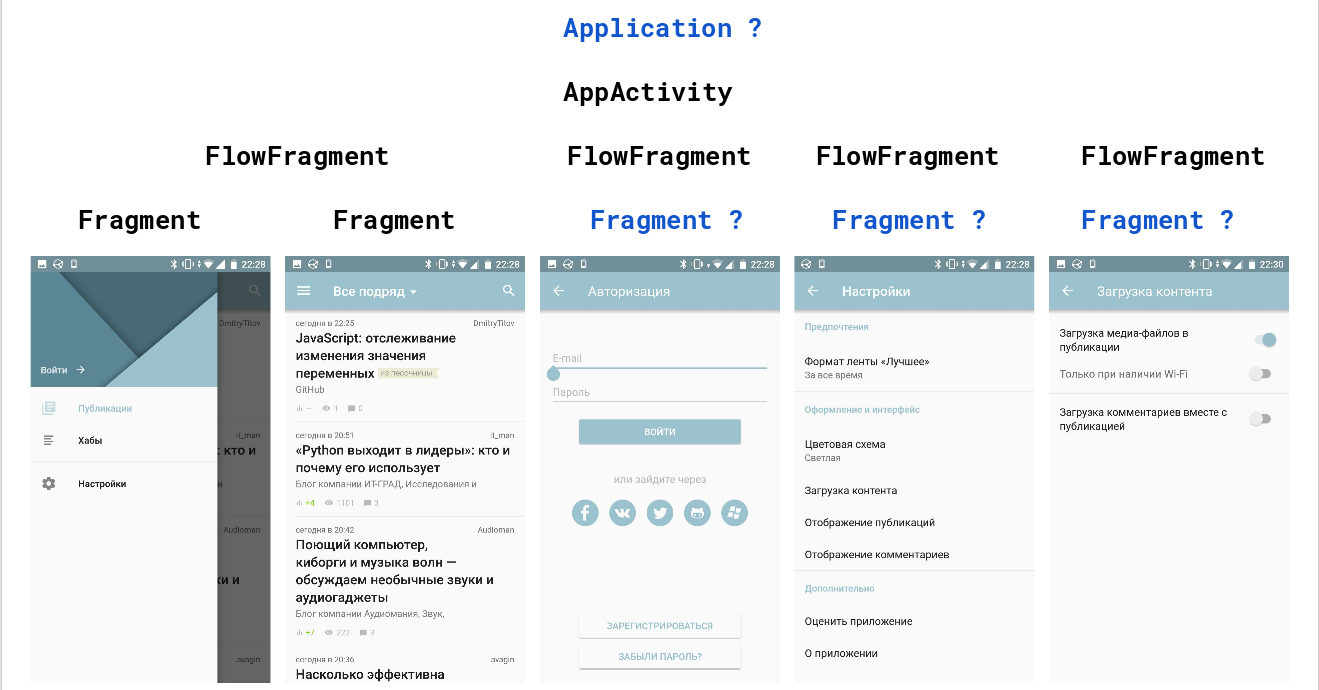

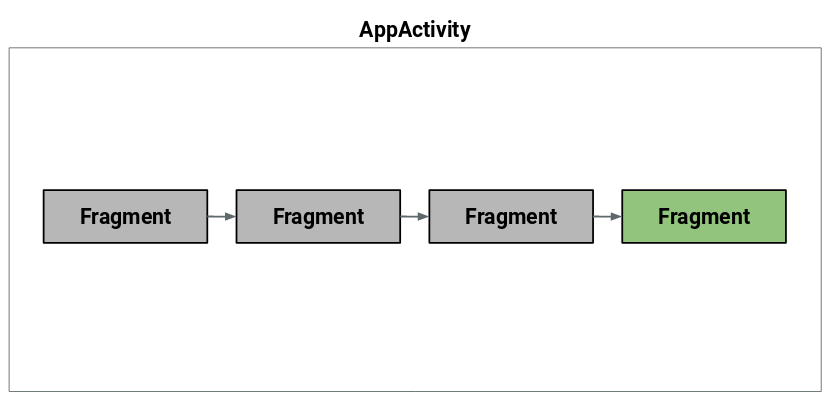

We made only two changes: we added the AppActivity class and replaced all the Activities with FlowFragment. Consider each change in more detail.

What is AppActivity responsible for:

- contains only a container for fragments

- is the initialization point of UI scop objects (earlier it was necessary to do this in Application, which is wrong, because, for example, the services in our application do not exactly need such objects)

- is a lifecycle provider application

- brings all the advantages of a single-activity.

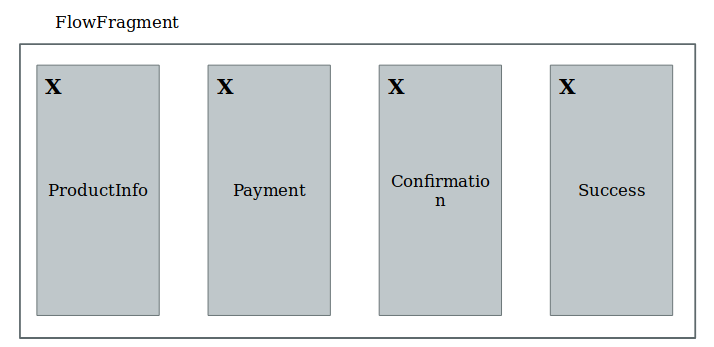

What is FlowFragment :

- does exactly the same as the Activity that was created instead.

New navigation

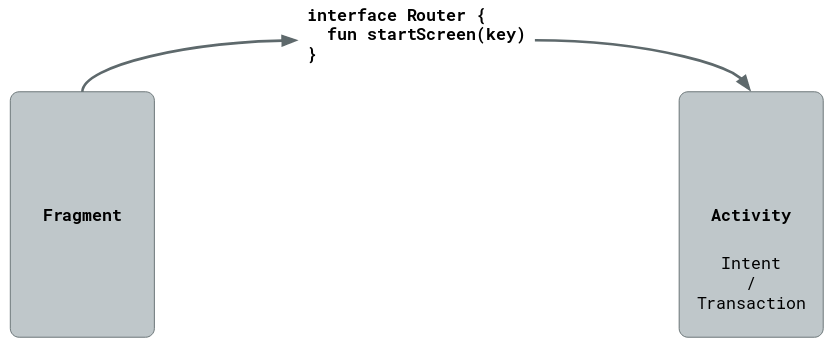

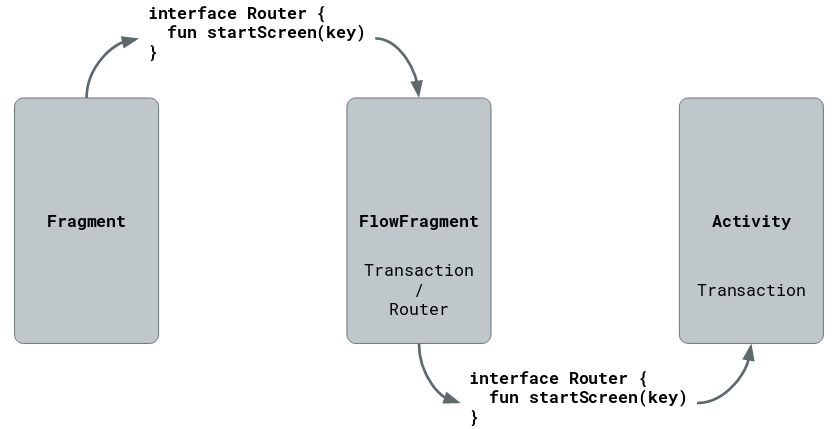

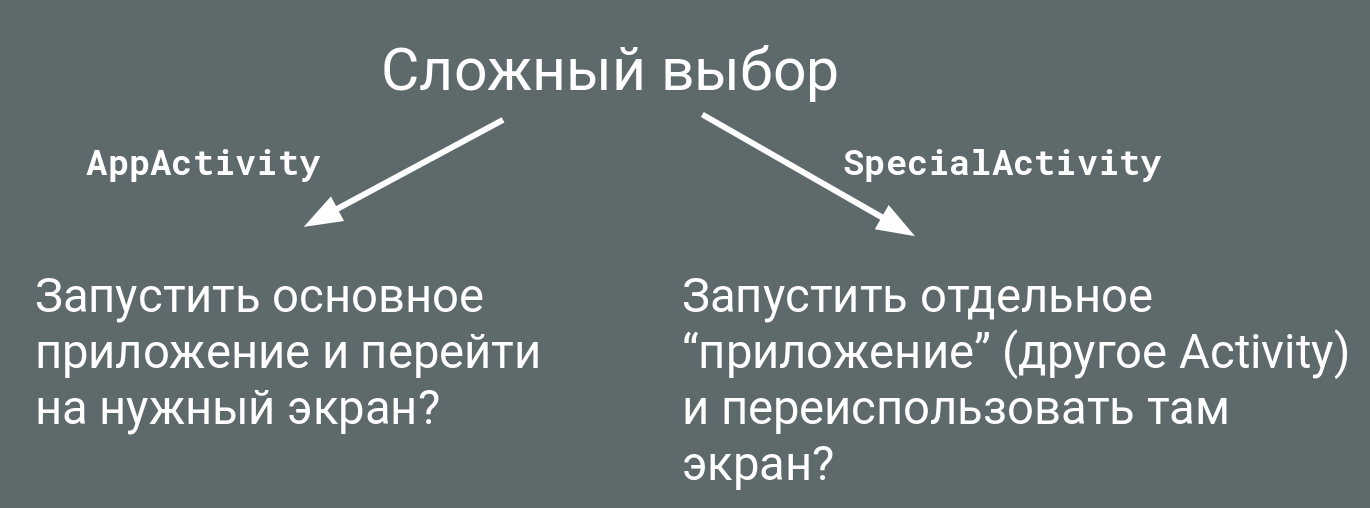

The main difference from the old approach is navigation.

Previously, the developer had a choice: to launch a new Activity or a fragment transaction in the current one. The choice has not disappeared, but the methods have changed - now you have to decide whether to start the fragments transaction in AppActivity or inside the current FlowFragment.

Similarly, with the processing of the Back button. Previously, the Activity passed the event to the current fragment, and if it did not process it, it made the decision itself. Now AppActivity sends the event to the current FlowFragment, and that, in turn, sends it to the current fragment.

Transfer the result between screens

For inexperienced developers, the issue of data transfer between screens is the main problem of the new approach, because before it was possible to use the startActivityForResult () functionality!

Not the first year various architectural approaches to writing applications are discussed. The main task here is the separation of the UI from the data layer and the business logic. From this point of view, startActivityForResult () breaks the canon, since the data between the screens of one application is transmitted on the side of the UI layer entities. I emphasize that it is exactly one application, since we have a common data layer, common models in the global scopa, and so on. We do not use these opportunities and drive ourselves into the framework of one Bundle (serialization, size, and more).

My advice : do not use startActivityForResult () inside the application! Use it only for its intended purpose - to launch external applications and get results from them.

How then to launch the screen with a choice for other screen? There are three options:

- TargetFragment

- Eventbus

- reactive model

TargetFragment is an out-of-box option, but the same data transfer is on the UI layer side. Bad option.

EventBus - if you can agree in a team and - most importantly - monitor the arrangements, then on the global data bus you can implement data transfer between screens. But since this is a dangerous move, the conclusion is a bad option.

Reactive model - this approach implies the presence of callbacks and nothing more. How you implement them is decided by the team of each project. But it is this approach that is optimal, as it provides control over what is happening and does not allow using the code for other purposes. Our choice!

Total

I love new approaches when they are simple and have clear benefits. I hope that in this case it is. The benefits are described in the first part, and the difficulty of judging you. It is enough to replace all the Activity with FlowFragment, keeping all logic unchanged. Slightly change the navigation code and think about working with transferring data between screens, if this has not already been done.

To show the simplicity of the approach, I myself translated the open application to a Single-Activity, and it took only a few hours (of course it is worth considering that this is no older than Legacy, and everything is more or less good with architecture).

What happened?

Let's see how now to solve standard problems in a new approach.

BottomNavigationBar and NavigationDrawer

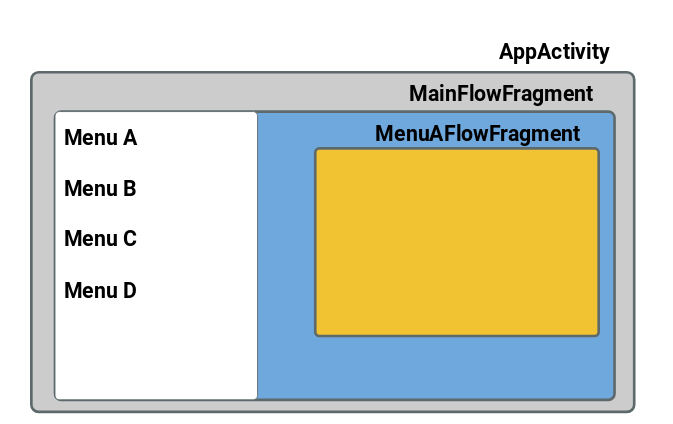

Using the simple rule that we replace all Activity with FlowFragment, the side menu will now be in a certain fragment and switch nested fragments in it:

Similar to BottomNavigationBar.

Much more interesting is that some FlowFragment we can invest in others, because these are still ordinary fragments!

This option can be found in GitFox .

It is the ability to simply combine some fragments inside others without any problems to make a dynamic UI for different devices: tablets + smartphones.

Di scopes

If you have a flow of purchase of goods from several screens, and on each screen you need to show the name of the product, you probably already carried it into a separate Activity, which stores the product and provides it with screens.

It will be the same with FlowFragment - it will contain a DI-scop with models for all nested screens. This approach eliminates the difficult time management of the life of a scop, tying it to the lifetime of the FlowFragment.

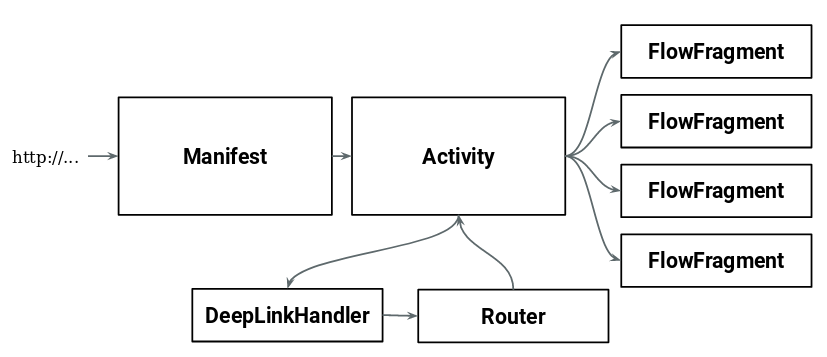

Deep-links

If you used filters in the manifest to launch via a deep-link specific screen, you might have problems starting the Activity, which I wrote about in the first part. In the new approach, all deep-link fall into AppActivity.onNewIntent. Further, according to the data obtained, a transition occurs to the required screen (or a chain of screens. I suggest looking at this functionality in Chicheron ).

Death process

If the application is written on several Activities, you should know that when the application dies, then when the process is restored, the user will be on the last Activity, and all previous ones will be restored only when they are returned to them.

If this is not taken into account in advance, problems may arise. For example, if the scop needed for the last Activity was opened at the previous one, no one will recreate it. What to do? Bring it to the Application class? Make a few points of opening scop?

Everything is easier with fragments, as they are inside an Activity or another FlowFragment, and any container will be restored BEFORE re-creating the fragment.

Other practical problems can be discussed in the comments, because otherwise there is a chance that the article will be too voluminous.

And now the most interesting part.

Narrow places (remember and think).

Here are collected important things that you should think about in any project, but everyone is so accustomed to “podkostilivat” in projects for several Activities, which is worth recalling and telling how to solve them correctly in a new approach. And first on the list

Screen rotation

That most terrible fairy tale for fans to whine that Android recreates Activity when turning the screen. The most popular solution method is fixing the portrait orientation. Moreover, this proposal is no longer developers, but managers, frightened by phrases like " supporting a turn is very difficult and costs several times more ."

We will not argue about the correctness of such a decision. Another thing is important: the fixation of the rotation does not exempt from the treatment of death Since the same processes occur when many other events occur: split-mode, when several applications are displayed on the screen, connecting an external monitor, changing the application configuration on the fly, and so on.

Moreover, the screen rotation allows you to check the correct “rubberiness” of the layout, so in our St. Petersburg team we do not disable the rotation on all debug builds, even if it isn’t in the release version. Not to mention the typical bugs that will still be found during the check.

Many solutions have already been written to handle the rotation, starting with Moxy and ending with various MVVM implementations. Make it no more difficult than anything else.

Consider another interesting case.

Imagine a product catalog application. We do it in Single-Activity. Everywhere the portrait mode is fixed, but the customer wants a feature when, when viewing a photo gallery, a user can watch them in landscape orientation. How to support this?

Someone will offer the first crutch :

<activity android:name=".AppActivity" android:configChanges="orientation" /> override fun onConfigurationChanged(newConfig: Configuration?) { if (newConfig?.orientation == Configuration.ORIENTATION_LANDSCAPE) { //ignore } else { super.onConfigurationChanged(newConfig) } } Thus, we can not call super.onConfigurationChanged(newConfig) , but process it ourselves and rotate only the necessary views on the screen.

But with API 23, the project will crash with SuperNotCalledException , so a bad choice .

In the statements above, an error was made:

I was reasonably corrected in the comments that it is enough to add android: configChanges = "orientation | screenSize", and then you can call super when the turn is over and the Activity will not be recreated. It is useful to use when on the screen a webview or a map that is long initialized, and this one wants to avoid.

This will help solve the described case with the gallery, but the main message of this section is: do not ignore the re-creation of the Activity , this can happen in many other cases.

Someone may suggest another solution:

<activity android:name=".AppActivity" android:screenOrientation="portrait" /> <activity android:name=".RotateActivity" /> But in this way we move away from the Single-Activity approach for solving a simple task and deprive ourselves of all the benefits of the approach. This is a crutch, and a crutch is always a bad choice .

Here is the right decision:

<activity android:name=".AppActivity" android:configChanges="orientation" /> override fun onResume() { super.onResume() activity?.requestedOrientation = ActivityInfo.SCREEN_ORIENTATION_SENSOR } override fun onPause() { super.onPause() activity?.requestedOrientation = ActivityInfo.SCREEN_ORIENTATION_PORTRAIT } That is, when a fragment is opened, the application starts to “spin”, and when it returns, it is fixed again. According to my observations, this is how the AirBnB application works . If you open the view of housing photos, cornering is activated, but in landscape orientation you can pull the photo down to exit the gallery. Below it, the previous screen in landscape orientation will be visible, which you usually will not find, since immediately after leaving the gallery the screen will turn into a portrait and fix.

This is where the timely preparation for screen rotation will help.

Transparent status bar

Only Activity can work with the system bar, and now it’s only one for us, so you should always specify

<item name="android:windowTranslucentStatus">true</item> But on some screens there is no need to "crawl" under it, and you need to display all the content below. The flag comes to the rescue

android:fitsSystemWindows="true" which indicates the layout that you should not draw under the system bar. But if you specify it in the layout of the fragment, and then you try to display the fragment through the transaction in the fragment manager, then you will be disappointed ... it will not work!

The answer is quickly googled

I highly recommend that you read, there is a really comprehensive answer and many useful links.

A quick and working ( but not the most correct ) solution is to wrap the layout in CoordinatorLayout

<android.support.design.widget.CoordinatorLayout xmlns:android="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res/android" xmlns:app="http://schemas.android.com/apk/res-auto" android:layout_width="match_parent" android:layout_height="match_parent" android:fitsSystemWindows="true"> </android.support.design.widget.CoordinatorLayout> A better solution helps to handle and keyboard.

Change the layout when the keyboard appears

When the keyboard leaves, the layout should be changed so that the important elements of the UI do not remain out of reach. And if earlier we could specify different modes of reaction to the keyboard for different Activities, now we need to do this in Single-Activity. Therefore it is necessary to use

android:windowSoftInputMode="adjustResize" If you use the approach from the previous section for processing the transparent status bar, you will find an annoying error: if the fragment successfully “crawled” under the status bar, then when the keyboard appears, it will shrink from the top and bottom, since both the status bar and the keyboard inside the system work through SystemWindows .

Note the title

What to do? Learn the documentation! Chris Banes WindowInsets .

WindowInsets

- ( 51dp)

- ( !)

- .

WindowInsets!

Splash screen

- , Splash screen — , , , , Activity . .

, Single-Activity, Splash screen. , deep-link Splash screen .

, , , .

, . Single-Activity. - , , .

...

Intent, , ...

What's next? :

- , «». «», . , !

- , …

, . ? — «» «» .

What to do? , .

Activity!

, : , — .

— , ( Activity), .

Activity — . Activity, . .

Conclusion

() , Activity, Android-. , .

: Google . — , , Activity .

, , , ! Thank!

')

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/426617/

All Articles