From Space Invaders to Half Life 2: the story of gaming dizdokov

Ideas may appear from everywhere, but at a certain stage at the beginning of development, before the eyes of all its participants, there should already be a clear plan. Throughout the history of video games, game creators have left valuable information about the sources of their inspiration in the texts, which we collectively call "design documents." From visualizations to project planning, from code to creative solutions, all these papers and digital data are themselves art. Let's look at how games have been created for decades, with examples of such rare, but always amazing artifacts.

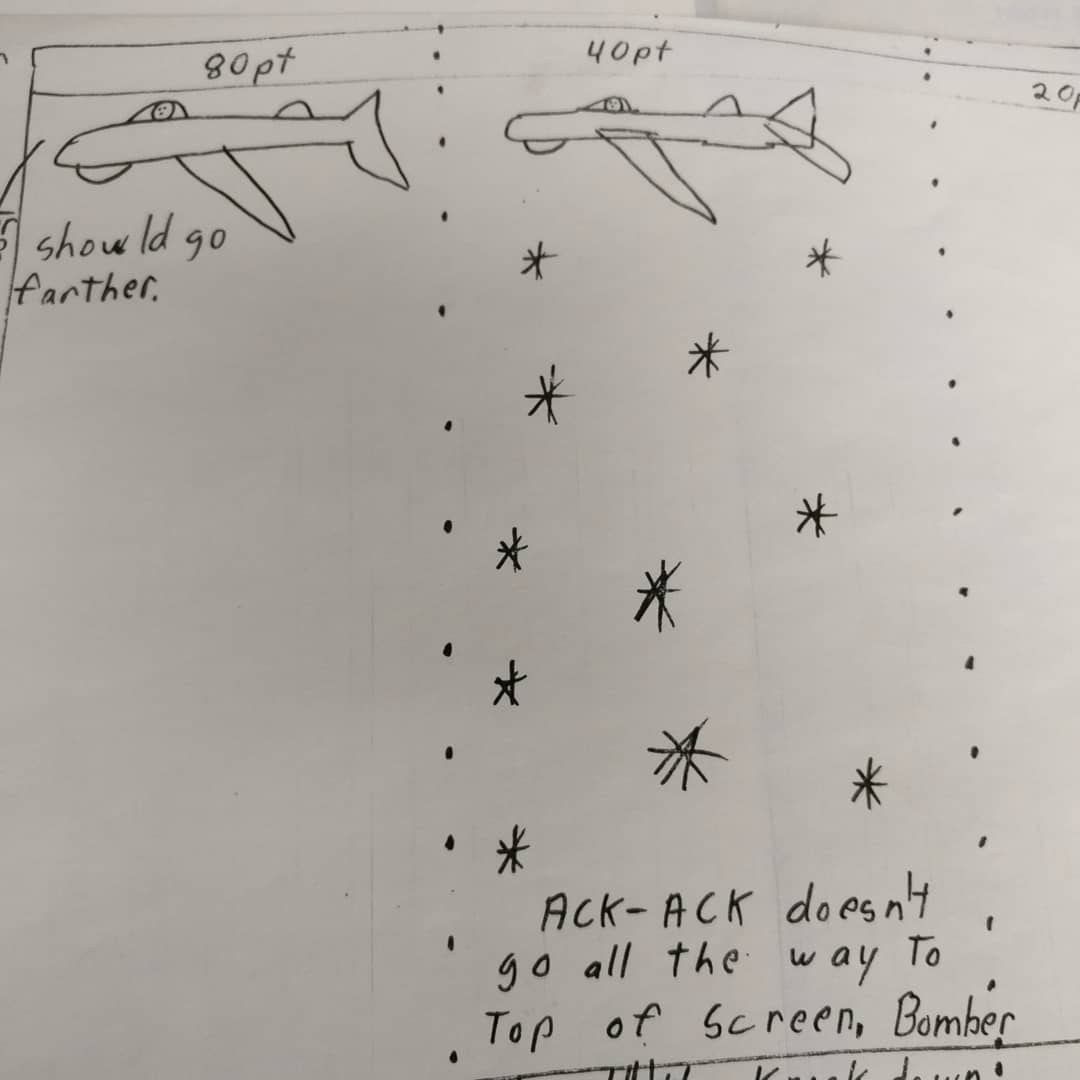

Flying Fortress Concept.

In my own experience, one of the most effective ways to quickly create a game is to draw a visualization of how the screen should look. The drawing will tell everyone involved in the project how the game literally should look like and how the user will interact with it. Although the development of games at the beginning of their history was usually a matter of one or two people, creating a scheme of all the screen elements is still useful. The same applied to Darrell Jay Bledowski with his 1976 Flying Fortress game. Blendowski created an annotated scheme that described both gameplay and control. He divided the screen into points and added important notes, for example: “ACK-ACK does not move across the top of the screen” and “must move on” describing his thought process. This is one of the first surviving design documents, it is complete and reflects the process of solving the problem.

Frog animation sprites (Bill Blewett)

')

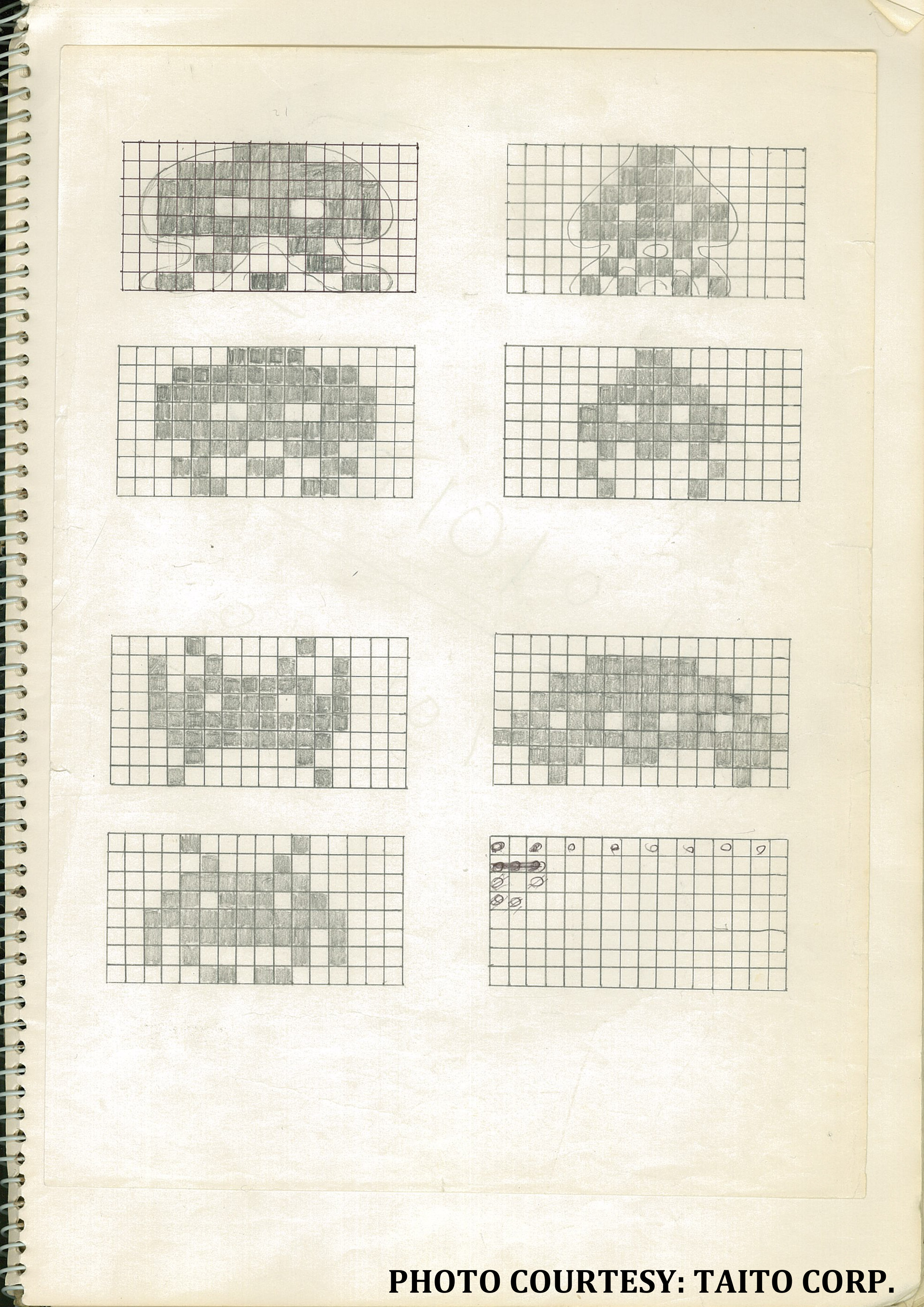

Sprites Space Invaders (Taito Corp)

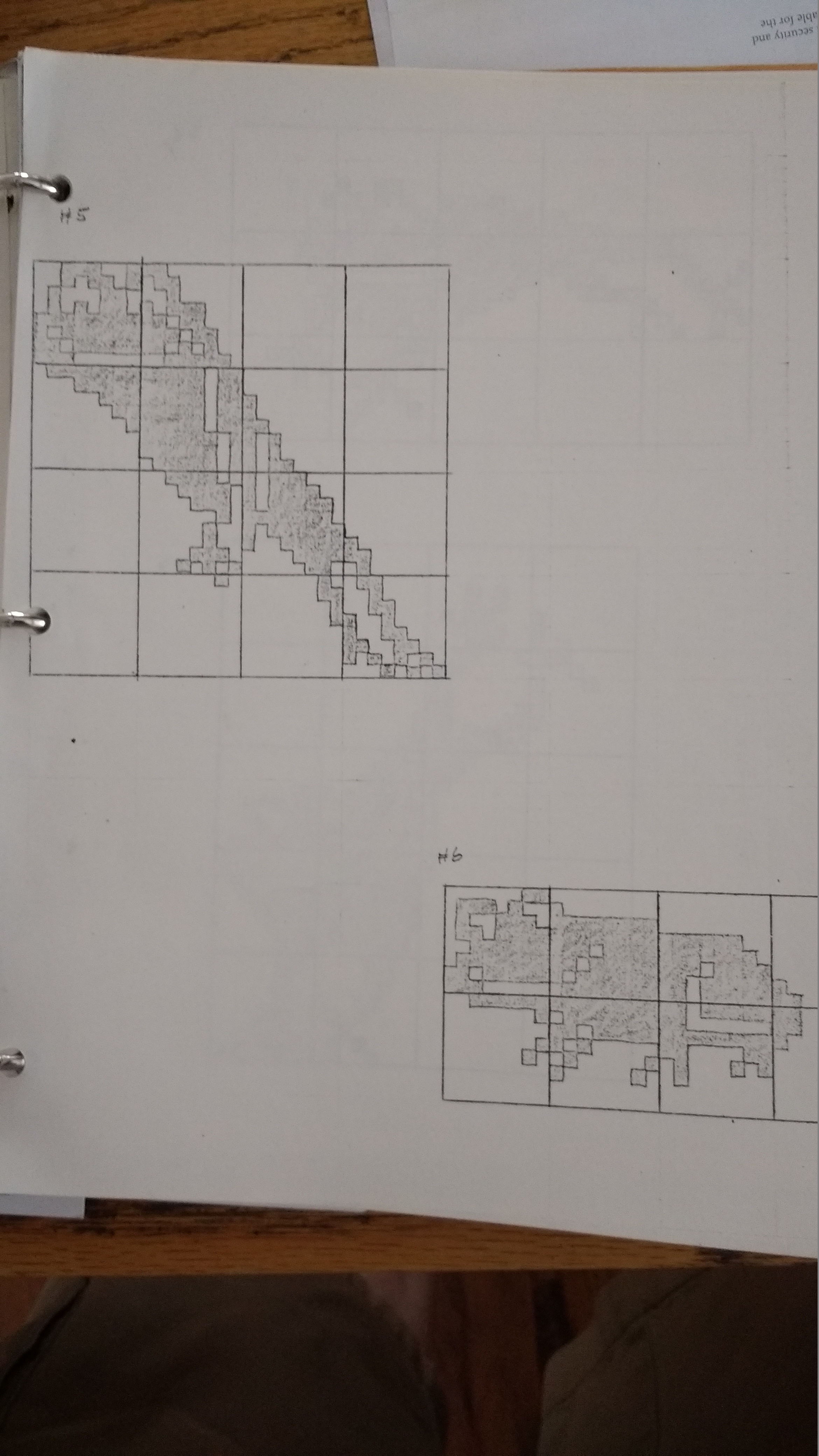

Although it is quite normal to begin with creating an approximate outline of what should be on the screen, it is also necessary to mark the graphics in the form understood by computers. Graph paper has always been a friend of technical gurus, and has played a crucial role in the work. The development on the checkered grid not only helped to understand how everything would look on the screen, but was also incredibly useful for implementing tricks - repeating the same lines or reusing sprites. Often these grids served as the basis for entering hexadecimal information, because not every user had tools for creating sprites. Both Bill Bluet and Tomohiro Nisikado had utility programs, but they still needed a design circuit to turn bits into pixels.

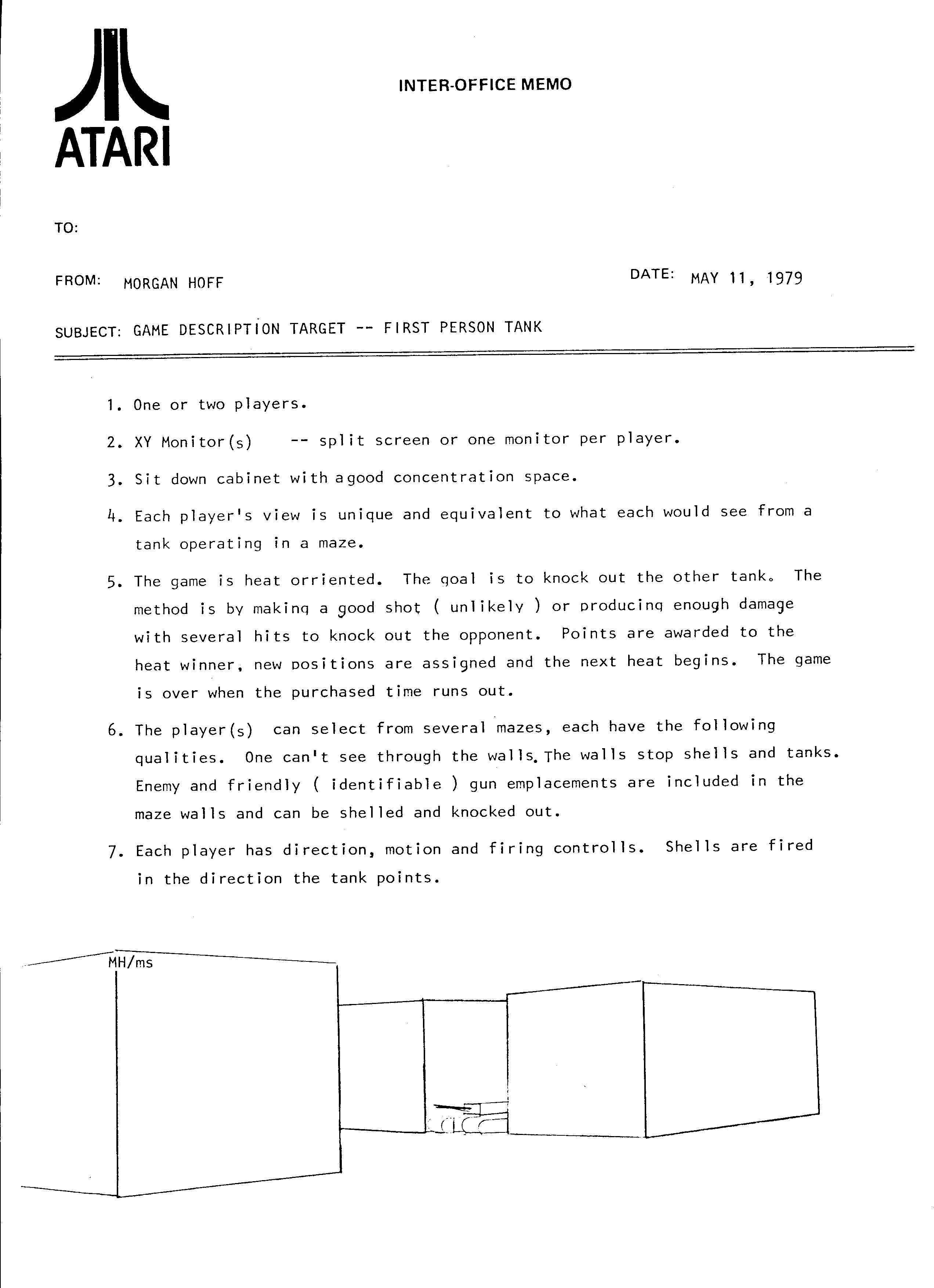

An early description of the game Battlezone ( Atari )

Times have changed, and the games became more difficult. Development companies felt the need to streamline ideas and the game development process in a form that could be referenced. Of course, the leader of such research was Atari, and one of the most unique collections was collected for the Battlezone. It is unique in that the developers demonstrated a partially formalized, partially improvisational approach to the development methodology. There are jokes in the document, for example, “To destroy an enemy tank, you need to get into it exactly (but this is unlikely)”, as well as a rough sketch of the game. From an early outline, one can understand that the idea of Battlezone has already appeared, but the game has not yet taken its real form. This "beta" version of the game was much more like Tank than anything else. Over time, the authors created a formalized visualization , which is much more like a finished game, but with a more optimistic view of the amount of information displayed, which then had to be reduced.

Application document of the game Joust ( Patrick Scott Patterson )

Atari decided to use the “item list” principle to quickly bring in large groups of developers. However, documents could be sent to specific people, and this approach was chosen by John Newcammer when he wrote the application for Joust. Guided by the main aspects that should be taken into account in the production, it was necessary first of all to describe the main goal of the game and explain why it will be interesting. Thus, Newkamer was able to get into the head of the player, and not leave the creation of an interesting design for later. In his terrific handwritten script, he briefly described the game as follows: "Strategic gameplay is a combination of playing riders with a race for survival." The era of elevator pitch began with this document.

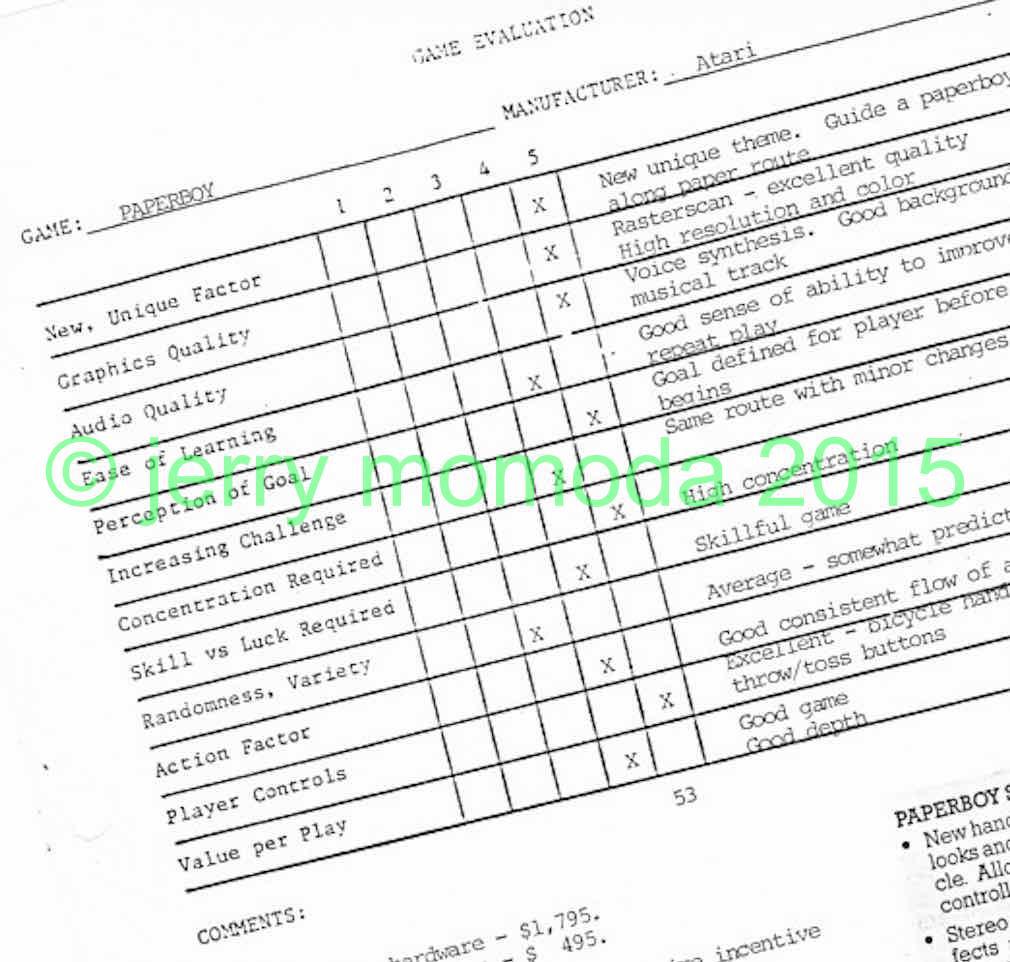

Paperboy game analysis ( Jerry Momoda )

However, the main part of the development is not in planning, but in actions. When the game can already be shown, the authors seek to demonstrate it to as many people as possible in order to get their feedback. Extracting useful information from such reviews is a puzzlingly difficult task, especially considering conflicting points of view. Jerry Momod of Nintendo based on player feedback created a rating system that was not just raw numbers. Such an analysis of the games of competitors, in this case, the paperboy of Atari Games, presented in a clear format, undoubtedly influenced the development process in terms of business and creativity. Mostly positive reviews can be nothing more than a signal of the future hit of the game, as happened in the Paperboy case.

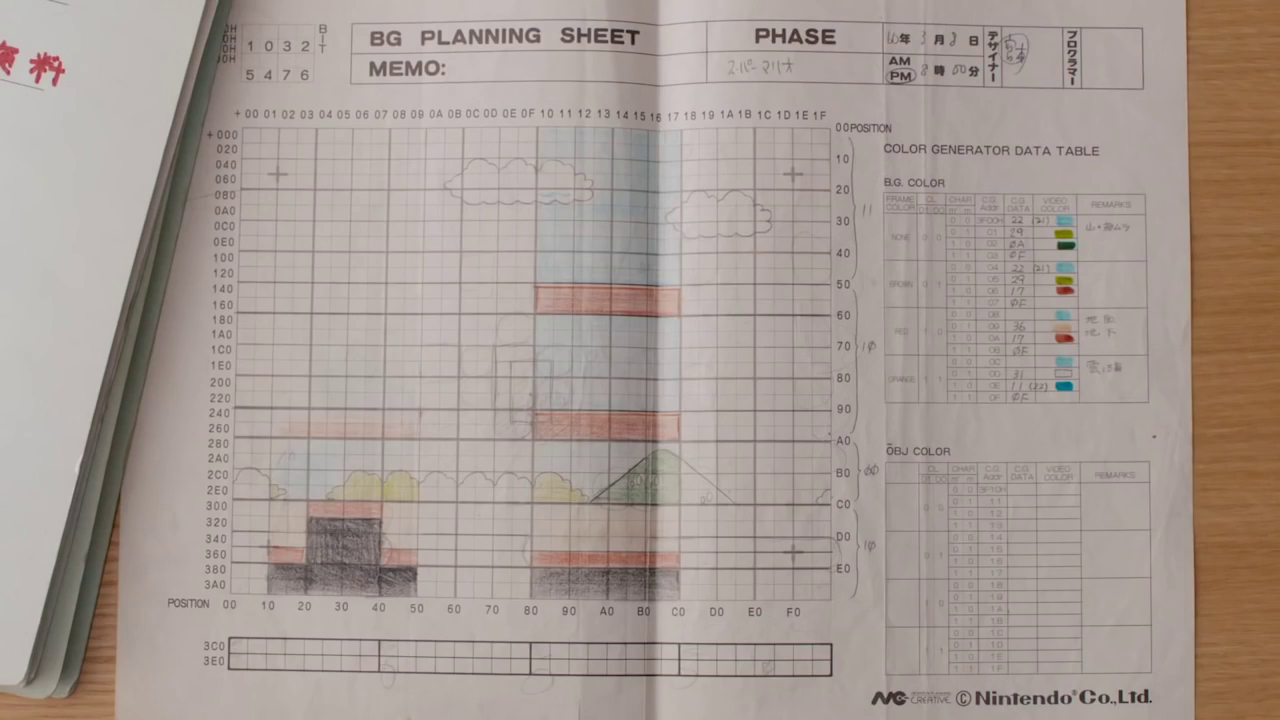

Routing Super Mario Bros. ( Nintendo )

Nintendo strictly formalized its game creation process using flow sheets. These cards were extremely useful, as they corresponded to the specifications of Famicom up to hexadecimal positions on the screen of each 8 × 8 tile. The main reason for the use of such maps was the definition of clever ways to reuse blocks, as well as strictly specified color resources. On the right side of the map, you can see the color palette of each object in the standard Super Mario Bros scene, defined by color and code. Such maps were well-ordered, they had special places for time and date, comments, meanings and other organizational aspects. From a technical point of view, they were very useful, but it seems that most of the creative work was done on a separate paper sheet. The developers even came up with a convenient way to overlay translucent paper on these cards to make changes.

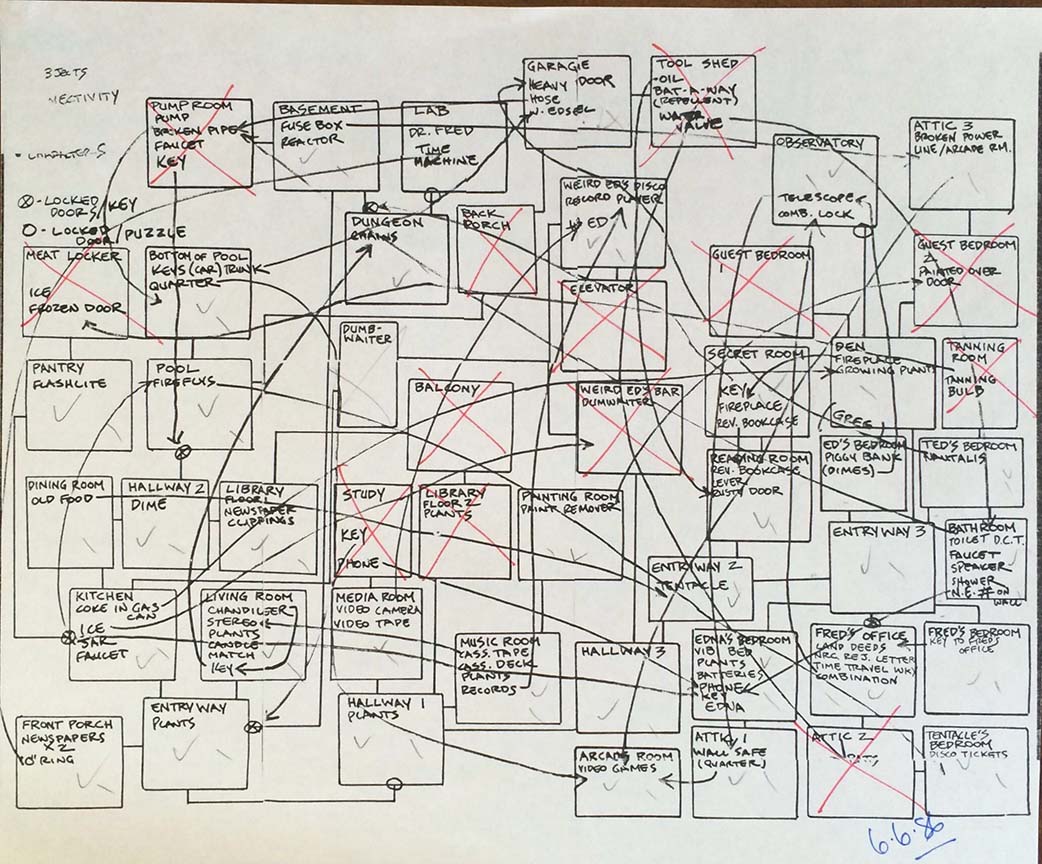

Map of Maniac Mansion ( Ron Gilbert )

Striving to expand the boundaries of creativity can make you look like Ron Gilbert with his Maniac Mansion flowchart. This is an example of the limitations of working on a single sheet of paper, unable to describe all the nuances of a non-linear game, especially when adding new ideas and abandoning them in the development process. Therefore, this attempt to streamline the mansion from the game turned out to be unable to describe anything but the only maniac - Ron Gilbert himself. Such rarely detectable first sketches are nonetheless important in that they demonstrate the usefulness of revising their plans. With all these extra rooms, the game would probably be much more confusing.

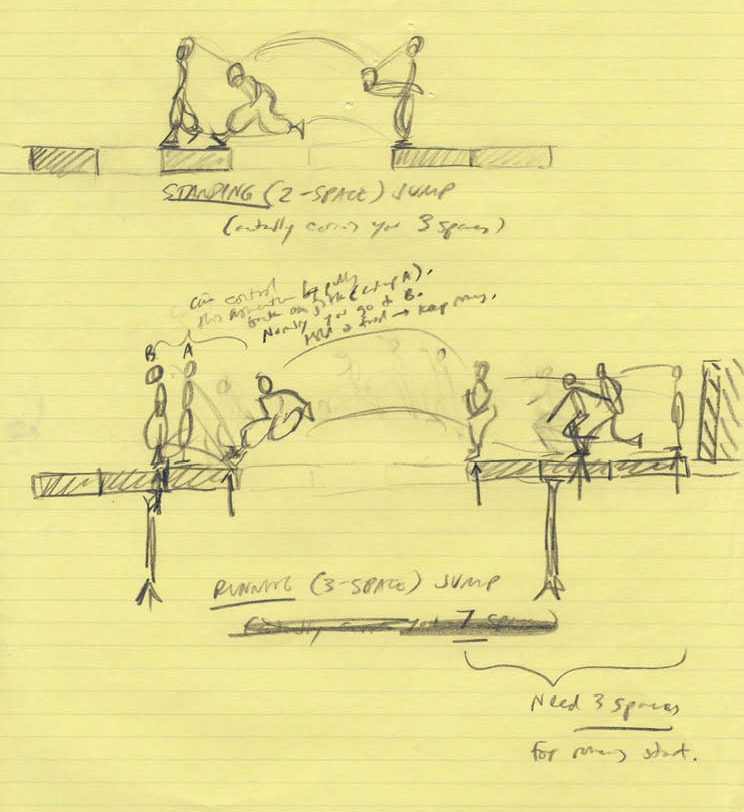

Design mechanic Prince of Persia ( Jordan Mechner )

With the approach of the 90s, a much greater understanding began to emerge that the design of games can be explained through language. Instead of describing the movement on an emotional level, Jordan Mekner was calculating the in-game distances necessary for the Prince of Persia to jump over a cliff. Thanks to this, all the tasks facing the player could be transferred to the code, and impossible jumps could be removed during testing. Pedantic Mekner wrote two whole books in which the development process is documented: from cutscene circuits to memory addresses and puzzles like “the prince from the mirror”. I highly recommend reading.

Application document for Street Fighter II ( Capcom )

By the time Street Fighter 2 was created, large development teams were already supposed to write large applications, which described the game’s detailed vision in an understandable form for everyone. They not only explained the prerequisites, the development process, the plot, but also gave a detailed description of the work of the game. It was necessary to present in an accessible format the frames of the animation, the arcs along which the characters move in a jump, the control and the characteristics of the characters. The game documentation itself turned into art, became a formal part of the production process. On the one hand, this meant that the management now understood how the games work, on the other - the developers realized what success they expected from them.

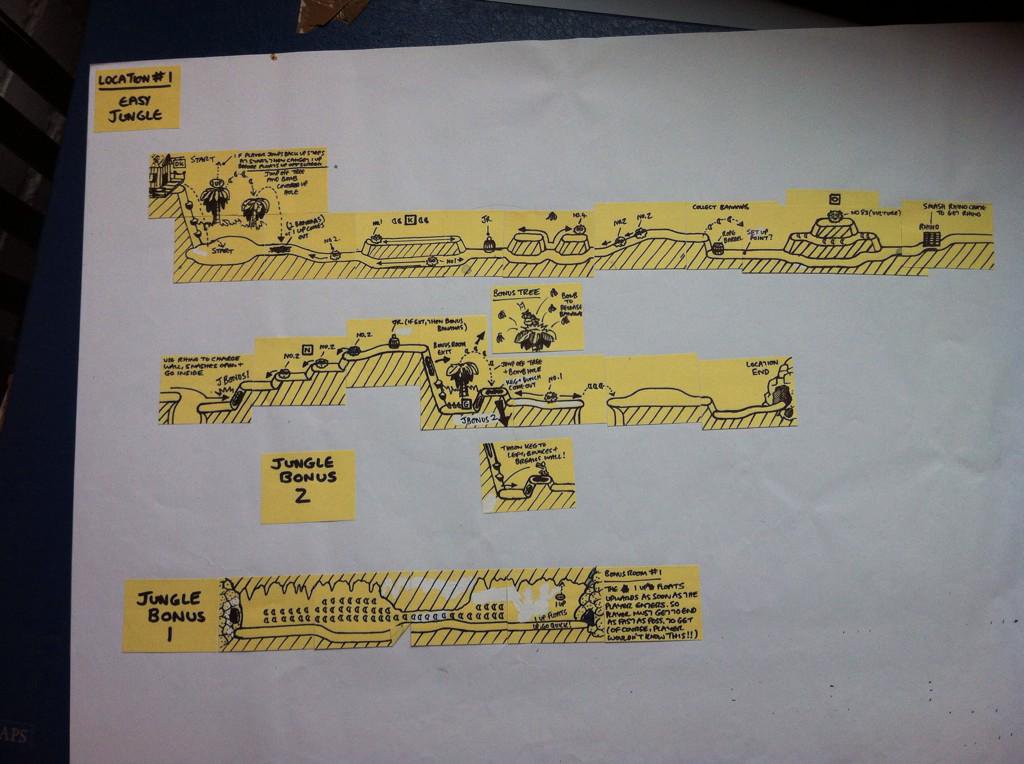

Easy Jungle level design from Donkey Kong Country ( Gregg Mayles )

Since we are still looking at the era of 2D games, I can't help but talk about the amazing technique of Donkey Kong Country designer Greg Meils. In order to achieve the feeling of a game with scrolling that would not fit on a sheet of paper, he created a series of drawings on note papers with a game plan. In the photo we can see a very accurate description of the first level with branches to the bonus rooms, providing non-linearity. Personally, I think this method is ingenious. Miles miraculously managed to keep these boards with records for so many years. His technique is clear, it can be tested, it is ideal for such an active game like DKC, which seems to be quite large, despite the small levels.

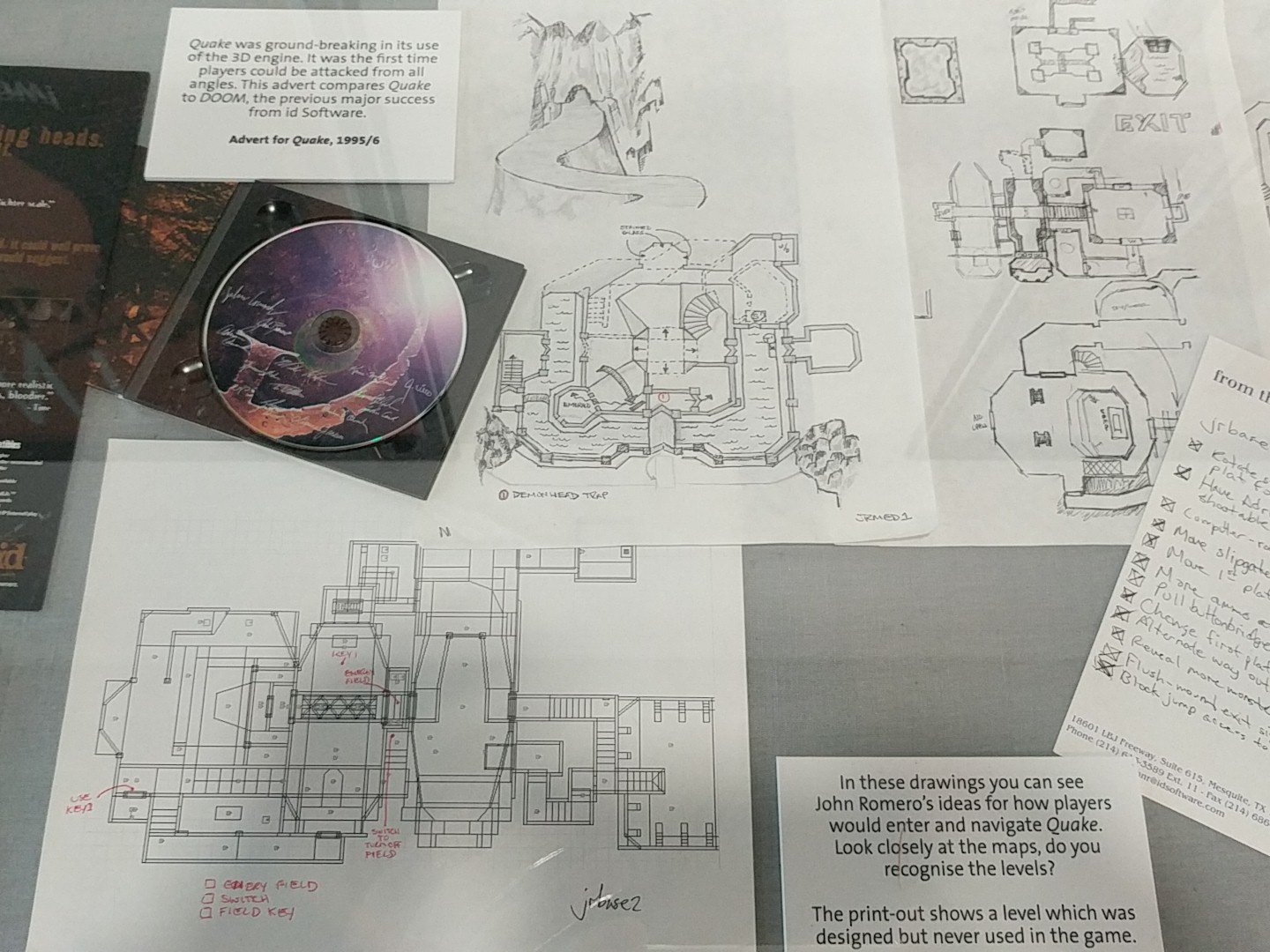

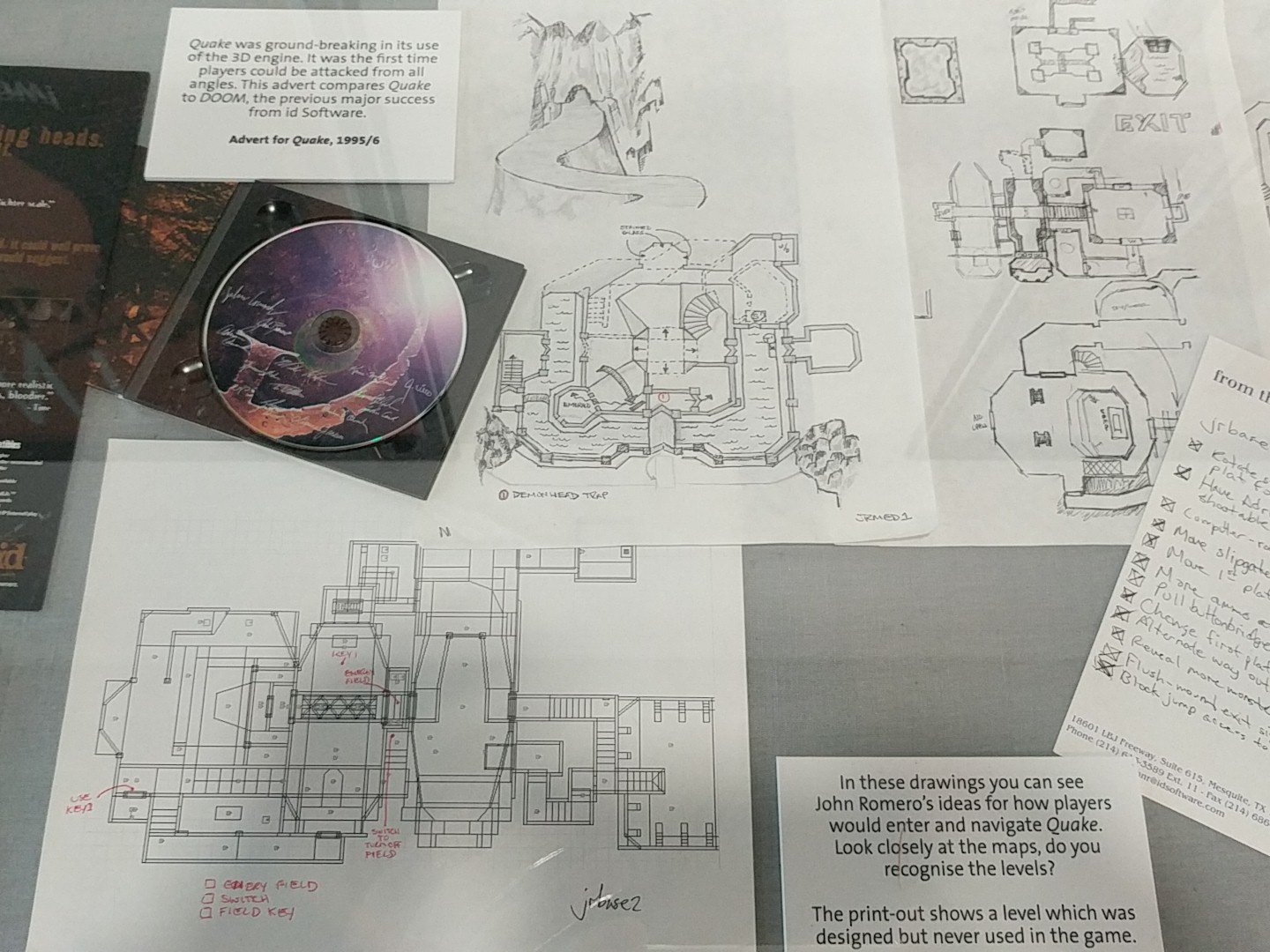

Maps for Quake ( John Romero )

However, in the case of 3D games, planning on paper without rethinking the methodology becomes more difficult. The iD Software guys were more like architects describing Quake landscapes in traditional top-down drawing schemes. They set the height through the texture, using dotted lines and arrows, denoting passages under the visible parts. This left a lot of space for creativity, it was possible to change the corners and add walls in the editor, but such drawings gave an understanding of what level they wanted to create. Using Quake’s tools, you could quickly build something and test it right away to test the strength of the idea.

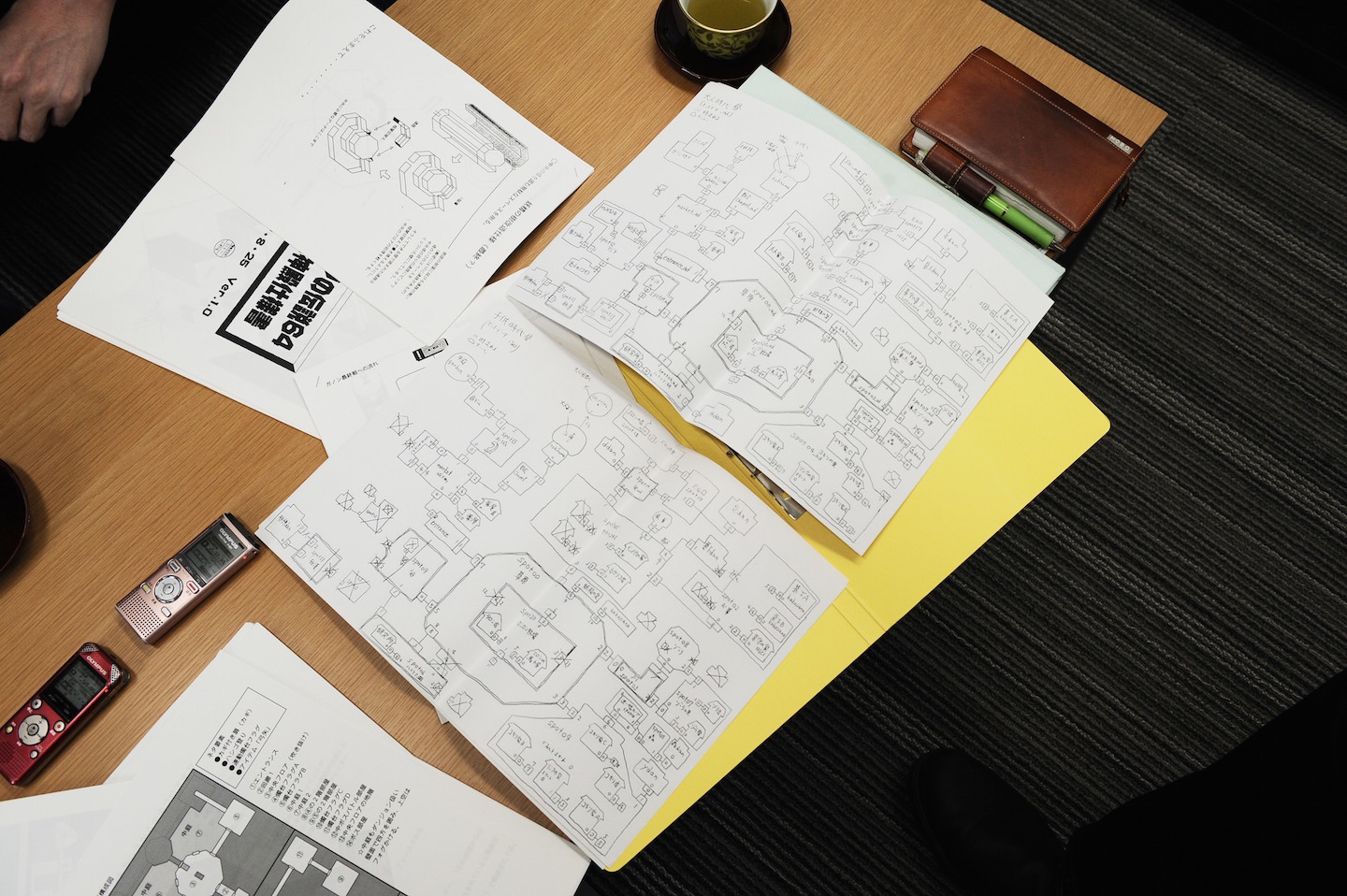

Map of the Water Temple of Ocarina of Time ( Denfaminicogamer )

The level for Quake is one thing, but how can you describe the Water Temple of Ocarina of Time? I'm not sure that Eiji Aonum himself knew this, but his two cards were an attempt to cope with this task. Aonuma marked each room of Water Temple with a number starting with Spot 00. He marked each door with two numbers indicating the number of steps required to enter this area, corresponding to another number in the room. From the document it is quite obvious that he modeled Water Temple as a very strict set of puzzles solved in a certain order, not quite understanding how bored a player would be if he did not think of a solution right away. Also in this document are the first computer visualizations that allow developers to understand what is actually happening in puzzles.

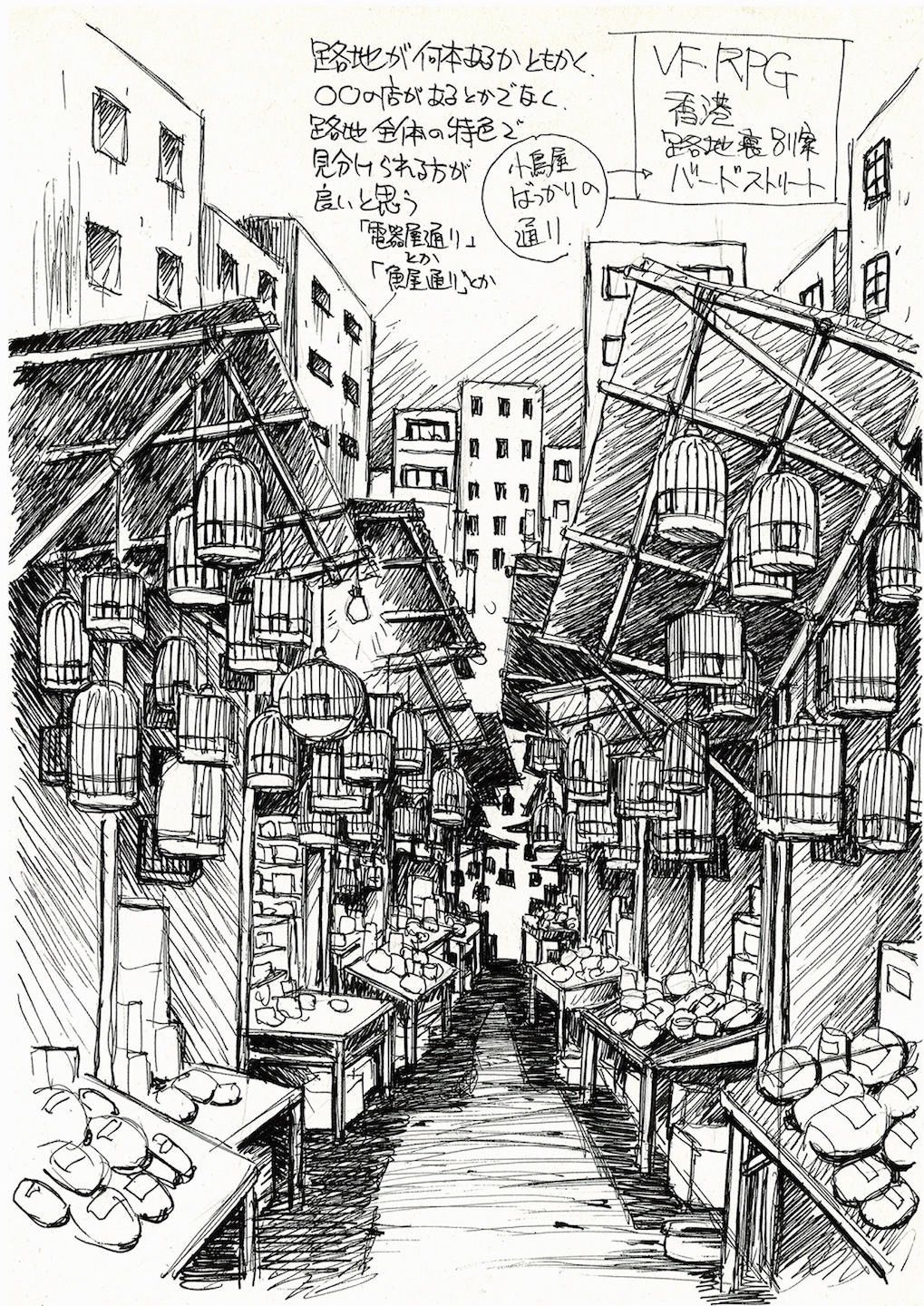

Shenmue Concept Art ( Denfaminicogamer )

Sometimes it is more than enough to simply set the mood of the scene. This drawing for Shenmue says almost nothing about the game (at least, for me, unable to read the text), except for the description of the entourage. Obviously, the game had to become very detailed, adorned with a multitude of empty objects that would nevertheless have to be modeled and textured. A clear sense of Japan — market stalls and paper lanterns — immediately bring about memories of Shenmue. And, of course, the important text above is the VF RPG (Virtua Fighter Role-playing Game). That is how it was perceived by the developers.

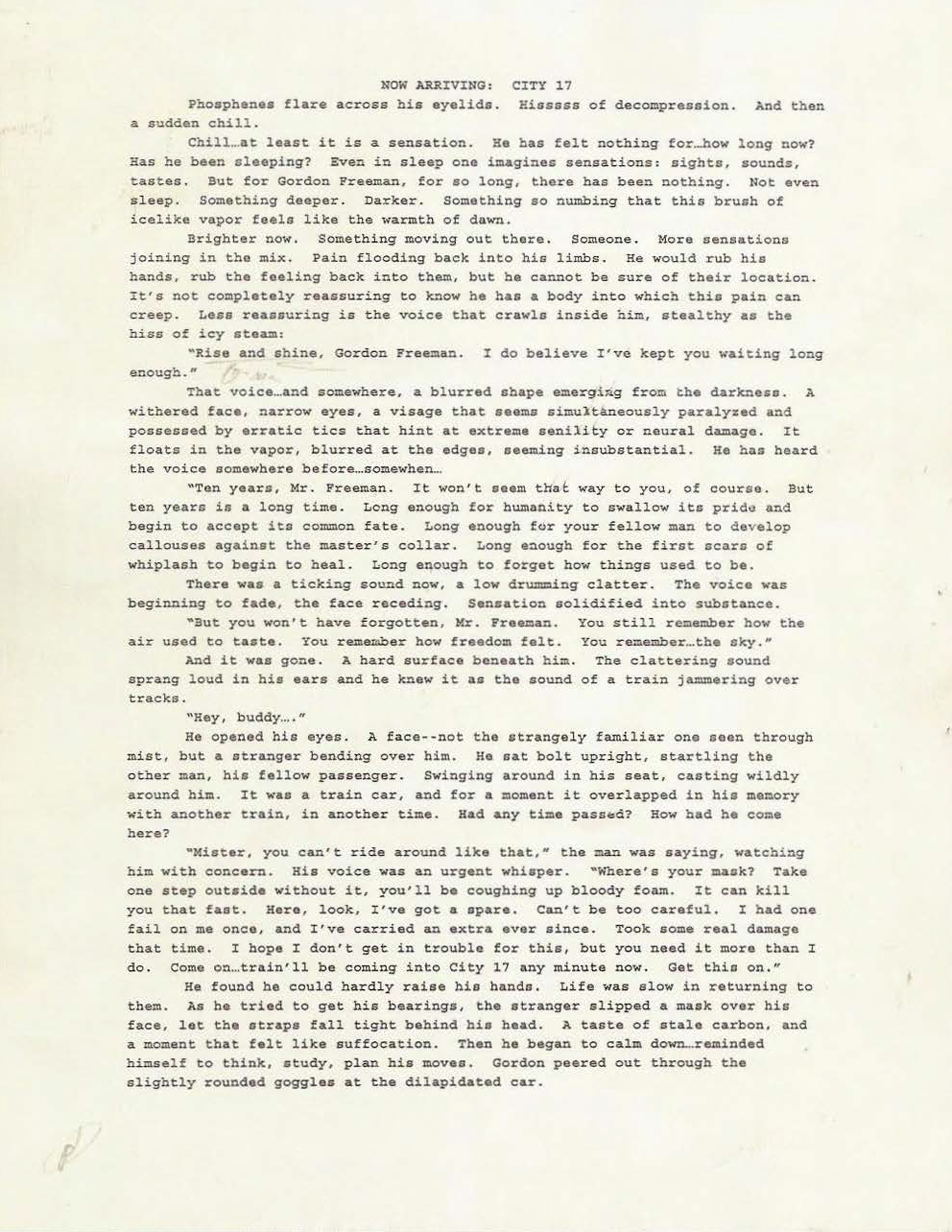

Fragment of the plot of Half-Life 2 ( Valve Software )

As a final topic, let's look at the often forgotten role in the development of the script writer. In most games the screenwriter is secondary, he writes on the basis of the developed entourage, but in Half-Life 2, this role was the exact opposite. Mark Laydlow wrote this piece in 2000 to inspire a lost development team. This passage most definitely would not have gotten into the game; it was needed just for a brief transfer of ideas, without relying on a document that would soon be thrown away.

I hope all these exhibits - from the most technically detailed to the most abstract - allowed you to get a valuable look at the process of creating games. All studios implement it in their own way, and they must continue to invest efforts to reflect their priorities and personality in the game. You should always strive for more.

Original author: Ethan Johnson

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/425453/

All Articles