Kotlin under the hood - look decompiled bytecode

Viewing Kotlin decompiled in Java bytecode is almost the best way to understand how it works and how some language constructs affect performance. Many of them have done it a long time ago, so this article will be especially relevant for beginners and those who have mastered Java a long time ago and decided to use Kotlin recently.

I specifically miss the rather battered and well-known moments, since it probably makes no sense to write about the generation of getters / setters for var and similar things for the hundredth time. So, let's begin.

')

How to view decompiled bytecode in Intellij Idea?

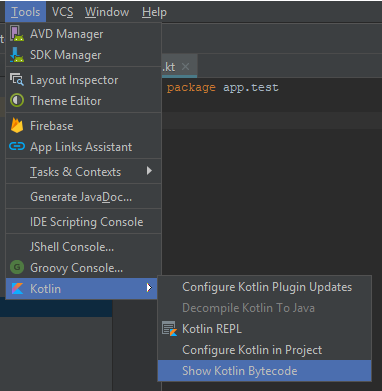

Quite simply - just open the file you need and select Tools -> Kotlin -> Show Kotlin Bytecode from the menu

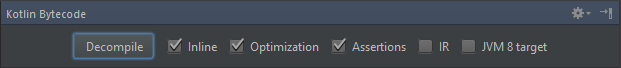

Further in the appeared window simply click Decompile.

The version Kotlin 1.3-RC will be used for viewing.

Now, finally, let's get to the main part.

object

Kotlin

object Test Decompiled java

public final class Test { public static final Test INSTANCE; static { Test var0 = new Test(); INSTANCE = var0; } } I suppose everyone who deals with Kotlin knows that an object creates a singleton. However, it is far from obvious to everyone what kind of singleton is being created and whether it is thread-safe.

From the decompiled code, you can see that the resulting singleton is similar to the eager implementation of the singleton, it is created at the moment when the classloader loads the class. On one side, the static block is executed when loaded with a classloader, which is thread-safe in itself. On the other hand, if there are more than one classroom, then you can not get rid of one instance.

extensions

Kotlin

fun String.getEmpty(): String { return "" } Decompiled java

public final class TestKt { @NotNull public static final String getEmpty(@NotNull String $receiver) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull($receiver, "receiver$0"); return ""; } } Here, in general, everything is clear - extensions are just syntactic sugar and compiled into the usual static method.

If someone got confused by the line with Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull, then everything is transparent there - in all functions with not nullable arguments, Kotlin adds a null test and throws an exception if you slipped a null

public static void checkParameterIsNotNull(Object value, String paramName) { if (value == null) { throwParameterIsNullException(paramName); } } What is characteristic if you write not a function, but an extension property

val String.empty: String get() { return "" } Then as a result we will get exactly the same thing that we got for the method String.getEmpty ()

inline

Kotlin

inline fun something() { println("hello") } class Test { fun test() { something() } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public final void test() { String var1 = "hello"; System.out.println(var1); } } public final class TestKt { public static final void something() { String var1 = "hello"; System.out.println(var1); } } With inline, everything is quite simple - a function marked as inline is simply completely inserted in the place from which it was called. What is interesting is that it itself also compiles static, probably for interoperability with Java.

All inline power is revealed at the moment when lambda is in the arguments:

Kotlin

inline fun something(action: () -> Unit) { action() println("world") } class Test { fun test() { something { println("hello") } } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public final void test() { String var1 = "hello"; System.out.println(var1); var1 = "world"; System.out.println(var1); } } public final class TestKt { public static final void something(@NotNull Function0 action) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(action, "action"); action.invoke(); String var2 = "world"; System.out.println(var2); } } At the bottom, statics is again visible, and at the top, one can see that the lambda in the function argument is also inline, and does not create an additional anonymous class, as is the case with the usual lambda in Kotlin.

Around this knowledge, inline in Kotlin, many end, but there are 2 more interesting points, namely, noinline and crossinline. These are keywords that can be added to a lambda argument in an inline function.

Kotlin

inline fun something(noinline action: () -> Unit) { action() println("world") } class Test { fun test() { something { println("hello") } } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public final void test() { Function0 action$iv = (Function0)null.INSTANCE; action$iv.invoke(); String var2 = "world"; System.out.println(var2); } } public final class TestKt { public static final void something(@NotNull Function0 action) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(action, "action"); action.invoke(); String var2 = "world"; System.out.println(var2); } } With such a record, the IDE begins to indicate that such an inline is useless a little less than completely. And compiles exactly the same as Java - creates Function0. Why decompiled with strange (Function0) null.INSTANCE; - I have no idea, most likely this is a decompiler bug.

Crossinline, in turn, does exactly the same as the usual inline (that is, if you do not write anything at all in front of the lambda), with a few exceptions, you cannot write return in the lambda, which is necessary to block the ability to abruptly terminate the function that calls the inline. In a sense, you can write, but firstly the IDE will swear, and secondly, when compiled we get

'return' is not allowed hereHowever, the crossinline bytecode does not differ from the default inline - the keyword is used only by the compiler.

infix

Kotlin

infix fun Int.plus(value: Int): Int { return this+value } class Test { fun test() { val result = 5 plus 3 } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public final void test() { int result = TestKt.plus(5, 3); } } public final class TestKt { public static final int plus(int $receiver, int value) { return $receiver + value; } } Infix functions are compiled as extensions to regular statics.

tailrec

Kotlin

tailrec fun factorial(step:Int, value: Int = 1):Int { val newValue = step*value return if (step == 1) newValue else factorial(step - 1,newValue) } Decompiled java

public final class TestKt { public static final int factorial(int step, int value) { while(true) { int newValue = step * value; if (step == 1) { return newValue; } int var10000 = step - 1; value = newValue; step = var10000; } } // $FF: synthetic method public static int factorial$default(int var0, int var1, int var2, Object var3) { if ((var2 & 2) != 0) { var1 = 1; } return factorial(var0, var1); } } tailrec is quite an amusing thing. As can be seen from the code, the recursion just gets distilled into a much less readable cycle, but the developer can sleep well, since nothing will fly out from Stackoverflow at the most unpleasant moment. Another thing in real life is to find the use of tailrec rarely.

reified

Kotlin

inline fun <reified T>something(value: Class<T>) { println(value.simpleName) } Decompiled java

public final class TestKt { private static final void something(Class value) { String var2 = value.getSimpleName(); System.out.println(var2); } } In general, about the very concept of reified and why it should be possible to write a whole article. If at a glance, then access to the type itself in Java in compile time is impossible, since before compiling java to know doesn't know what will be there at all. Kotlin is another matter. The keyword reified can only be used in inline functions, which, as already noted, are simply copied and pasted in the right places, so that during the “call” of the function, the compiler is already aware of what type there is and can modify bytecode.

It should be noted that a static function with a private access level is compiled in bytecode, which means that it will not work like this from Java. By the way, because of the reified advertising Kotlin "100% interoperable with Java and Android" turns out at least inaccuracy.

Maybe still 99%?

init

Kotlin

class Test { constructor() constructor(value: String) init { println("hello") } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public Test() { String var1 = "hello"; System.out.println(var1); } public Test(@NotNull String value) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(value, "value"); super(); String var2 = "hello"; System.out.println(var2); } } In general, with init, everything is simple - this is the usual inline function that executes before calling the code of the constructor itself.

data class

Kotlin

data class Test(val argumentValue: String, val argumentValue2: String) { var innerValue: Int = 0 } Decompiled java

public final class Test { private int innerValue; @NotNull private final String argumentValue; @NotNull private final String argumentValue2; public final int getInnerValue() { return this.innerValue; } public final void setInnerValue(int var1) { this.innerValue = var1; } @NotNull public final String getArgumentValue() { return this.argumentValue; } @NotNull public final String getArgumentValue2() { return this.argumentValue2; } public Test(@NotNull String argumentValue, @NotNull String argumentValue2) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(argumentValue, "argumentValue"); Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(argumentValue2, "argumentValue2"); super(); this.argumentValue = argumentValue; this.argumentValue2 = argumentValue2; } @NotNull public final String component1() { return this.argumentValue; } @NotNull public final String component2() { return this.argumentValue2; } @NotNull public final Test copy(@NotNull String argumentValue, @NotNull String argumentValue2) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(argumentValue, "argumentValue"); Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(argumentValue2, "argumentValue2"); return new Test(argumentValue, argumentValue2); } // $FF: synthetic method @NotNull public static Test copy$default(Test var0, String var1, String var2, int var3, Object var4) { if ((var3 & 1) != 0) { var1 = var0.argumentValue; } if ((var3 & 2) != 0) { var2 = var0.argumentValue2; } return var0.copy(var1, var2); } @NotNull public String toString() { return "Test(argumentValue=" + this.argumentValue + ", argumentValue2=" + this.argumentValue2 + ")"; } public int hashCode() { return (this.argumentValue != null ? this.argumentValue.hashCode() : 0) * 31 + (this.argumentValue2 != null ? this.argumentValue2.hashCode() : 0); } public boolean equals(@Nullable Object var1) { if (this != var1) { if (var1 instanceof Test) { Test var2 = (Test)var1; if (Intrinsics.areEqual(this.argumentValue, var2.argumentValue) && Intrinsics.areEqual(this.argumentValue2, var2.argumentValue2)) { return true; } } return false; } else { return true; } } } To be honest, I didn’t want to mention the date classes, which have already been said so much, but nevertheless there are a couple of moments worthy of attention. First, it is worth noting that only those variables that have been passed to the constructor fall into equals / hashCode / copy / toString. When asked why this is so, Andrei Breslav replied that taking the fields that were not transmitted in the constructor was also difficult and urgent. By the way, the date of the class cannot be inherited, though only because the inherited code would not be correct when inheriting . Secondly, it is worth noting the component1 () method to get the field value. As many componentN () methods are generated as there are arguments in the constructor. It looks useless, but actually it is necessary for the destructuring declaration .

destructuring declaration

For example, use the date class from the previous example and add the following code:

Kotlin

class DestructuringDeclaration { fun test() { val (one, two) = Test("hello", "world") } } Decompiled java

public final class DestructuringDeclaration { public final void test() { Test var3 = new Test("hello", "world"); String var1 = var3.component1(); String two = var3.component2(); } } Usually this feature is gathering dust on the shelf, but sometimes it can be useful, for example, when working with the contents of the map.

operator

Kotlin

class Something(var likes: Int = 0) { operator fun inc() = Something(likes+1) } class Test() { fun test() { var something = Something() something++ } } Decompiled java

public final class Something { private int likes; @NotNull public final Something inc() { return new Something(this.likes + 1); } public final int getLikes() { return this.likes; } public final void setLikes(int var1) { this.likes = var1; } public Something(int likes) { this.likes = likes; } // $FF: synthetic method public Something(int var1, int var2, DefaultConstructorMarker var3) { if ((var2 & 1) != 0) { var1 = 0; } this(var1); } public Something() { this(0, 1, (DefaultConstructorMarker)null); } } public final class Test { public final void test() { Something something = new Something(0, 1, (DefaultConstructorMarker)null); something = something.inc(); } } The keyword operator is needed in order to override any language statement for a particular class. Honestly, I have never seen anyone use this, but nevertheless there is such an opportunity, but there is no magic inside. In fact, the compiler simply replaces the operator with the desired function, just like typealias is replaced with a specific type.

And yes, if you are thinking about what will happen if you redefine the identity operator (=== which), then I hurry to upset, this is an operator that cannot be redefined.

inline class

Kotlin

inline class User(internal val name: String) { fun upperCase(): String { return name.toUpperCase() } } class Test { fun test() { val user = User("Some1") println(user.upperCase()) } } Decompiled java

public final class Test { public final void test() { String user = User.constructor-impl("Some1"); String var2 = User.upperCase-impl(user); System.out.println(var2); } } public final class User { @NotNull private final String name; // $FF: synthetic method private User(@NotNull String name) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(name, "name"); super(); this.name = name; } @NotNull public static final String upperCase_impl/* $FF was: upperCase-impl*/(String $this) { if ($this == null) { throw new TypeCastException("null cannot be cast to non-null type java.lang.String"); } else { String var10000 = $this.toUpperCase(); Intrinsics.checkExpressionValueIsNotNull(var10000, "(this as java.lang.String).toUpperCase()"); return var10000; } } @NotNull public static String constructor_impl/* $FF was: constructor-impl*/(@NotNull String name) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(name, "name"); return name; } // $FF: synthetic method @NotNull public static final User box_impl/* $FF was: box-impl*/(@NotNull String v) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(v, "v"); return new User(v); } @NotNull public static String toString_impl/* $FF was: toString-impl*/(String var0) { return "User(name=" + var0 + ")"; } public static int hashCode_impl/* $FF was: hashCode-impl*/(String var0) { return var0 != null ? var0.hashCode() : 0; } public static boolean equals_impl/* $FF was: equals-impl*/(String var0, @Nullable Object var1) { if (var1 instanceof User) { String var2 = ((User)var1).unbox-impl(); if (Intrinsics.areEqual(var0, var2)) { return true; } } return false; } public static final boolean equals_impl0/* $FF was: equals-impl0*/(@NotNull String p1, @NotNull String p2) { Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(p1, "p1"); Intrinsics.checkParameterIsNotNull(p2, "p2"); throw null; } // $FF: synthetic method @NotNull public final String unbox_impl/* $FF was: unbox-impl*/() { return this.name; } public String toString() { return toString-impl(this.name); } public int hashCode() { return hashCode-impl(this.name); } public boolean equals(Object var1) { return equals-impl(this.name, var1); } } Of the limitations - you can use only one argument in the constructor, however, it is understandable, given that the inline class is generally a wrapper over any one variable. An inline class may contain methods, but they represent the usual static. It is also obvious that all necessary methods have been added to support interop with Java.

Total

Do not forget that, firstly, the code is not always decompiled correctly, and secondly, not any code can be decompiled. However, the ability to watch the decompiled Kotlin code is in itself very interesting and can clarify a lot.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/425077/

All Articles