How does it work, and does conversational psychotherapy work at all

Hi, Habr!

Past my articles were devoted mainly to issues of pharmacology, but this is not really my topic, I am still a clinical psychologist (more recently), so today we will talk about conversational therapy in all its manifestations.

')

tl; dr : in a long and tedious article addresses the issue of the effectiveness of psychotherapy ( yes, effective, within its limits of applicability, of course ), and also provides reflections on how this effectiveness is achieved ( through the implementation of morphological and metabolic changes due to brain neuroplasticity ) .

At the end of the bonus for fans of video format (if there are any): record the presentation on the topic of this article: if you are lazy to read, you can see.

According to the definition adopted by the American Psychological Association, psychotherapy

For the purposes of this article, we will not draw a rigid distinction between psychotherapy proper and psychological counseling, which is defined as

In general, as you have already guessed, we will discuss all forms of interaction between the specialist and the client (doctor and patient), when the word effect is used: from classical psychoanalysis to modern behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches. Or, to put it more simply, about " talking with a psychologist / psychotherapist ."

Indeed, we live in the 21st century, more and more sophisticated psychiatric drugs intended for the treatment of a little less than all known mental disorders [3] enter the market every year, and the relevance of psychological / psychotherapeutic influences is questioned by many.

However, there are reasons for using conversational (non-drug) methods.

First , they are in some cases just as effective as drug treatment: in the case of depression [4,5], panic disorder , social phobia [5] and even psychosis [6].

Secondly , in some cases they are more effective than drugs: in the treatment of OCD [5], some types of depression [8].

Thirdly , often the joint use of drugs and psychotherapeutic methods is more effective than only drug treatment [6,7,45].

Fourth , in some cases they have fewer side effects and are more easily tolerated [6].

Fig. 2 Treatment with CPT and pharmacotherapy has led to a significant decrease in the activity of the tonsils in situations of anxiety. Source: [45]

Of course, I would not want the reader to have the wrong impression of psychotherapy as a panacea: in some cases, some methods of conversational influence are not only not useful, but also harmful (for example, "unstructured" types of psychotherapy when working with patients with borderline disorder personality ) [9]. Ultimately, the measure of therapeutic effects determines the doctor in each case .

The attentive reader may note that this section is about psychotherapy, but not about psychological counseling.

Indeed, the latter has been studied much worse - both because of the insufficiently developed research methodology ( how to evaluate the success of counseling during a divorce - not by the number of preserved marriages? ), And because of the much smaller prevalence of the principles of "evidence".

There are a great many types of psychotherapy [10]: cognitive , behavioral , cognitive-behavioral , rational-emotive-behavioral , narrative , psychodynamic , psychedelic , interpersonal , gestalt therapy , logotherapy , desensitization and processing by eye movement , etc.

Fig. 3 From the Freudian associations [first level] to modern methods of therapy based on the principles of evidence.

And each school claims to be effective. And in some areas there is quite imputed evidence base. At the same time, in most cases, explanations of this very efficiency are conducted through constructions adopted within the framework of this approach and are not quoted anywhere outside this framework.

For example, logotherapists believe that they achieve positive results by helping the patient find the meaning of life [11], supporters of the cognitive approach - by working with negative automatic thoughts [12], representatives of the psychodynamic direction - by working with the transference, drives and object relations [13], supporters of the psychedelic approach - due to the work with perinatal matrices and systems of condensed experience [14] and so on.

At the same time, the majority of such explanations lose all persuasiveness as soon as they fall outside the context of the theory that generated them. So, for example, the cognitive postulate that thoughts affect emotions [12] is completely unacceptable within the psychodynamic school, where a completely opposite view is used.

Contrary to the opinion prevailing in the domestic environment, proven clinical effectiveness ( to the extent that it complies with the principles of evidence-based medicine that is generally possible for psychotherapy ), it has not only cognitive-behavioral, but also, for example, psychodynamic therapy [15,16,17]. Those. Different therapies based on completely different sets of axioms show comparable effectiveness.

Modern authors note [10, p. 7190] that all approaches to psychotherapy have a common base that ensures efficiency:

One of the most interesting attempts to isolate and describe quantitatively the universal basis of successful therapy is the study of German authors [18], in which it was found that the predictor of the success of therapy is the difference in emotions that appear on the therapist’s face and those expressed by the client during the narration.

In other words, if during a first session a client with a sad face speaks about his pain (expressing " negative emotion "), and the therapist listens to him, showing interest and satisfaction (" positive emotion "), then the therapy is likely to be successful. If both express emotions of the same direction ("positive" / "negative"), then no.

The authors rather well formalized the testing procedure, having compiled a very limited “vocabulary” of emotions and selecting only those facial expressions that corresponded exactly to it. With regard to determining the success of therapy (also not the easiest task), estimates of the therapist, patient, and objective indicators of symptom reduction were used.

Their conclusions are quite different from the predictions and explanations that psychotherapists themselves give — they talk about anything: about motivational readiness, about the radical of the client’s personality, about the level of organization of that person, about the deep patterns — but not about the emotions that they express with their faces.

Such studies make us somewhat skeptical about the supposed mechanisms for realizing beneficial changes that psychotherapists / psychologists are talking about, and are pushing to find some more convincing ways to explain the existence of these very changes.

Some time ago, there was no way to objectively evaluate the effect of therapy on the brain, so psychotherapists made the most courageous (and often incorrect) assumptions about the presence and nature of such an effect.

Naturally, this situation could not last forever, and as soon as researchers had available methods for imaging the brain ( PET , MRI , fMRI , SPECT ), studies were published that aimed to determine the extent of the impact (or lack thereof) of conversational therapy on the physiological substrate of the brain .

Identifying this influence would solve several important problems - from proving that conversational therapy works at all , to understanding how it works, whether there is a difference between different types of therapy, etc.

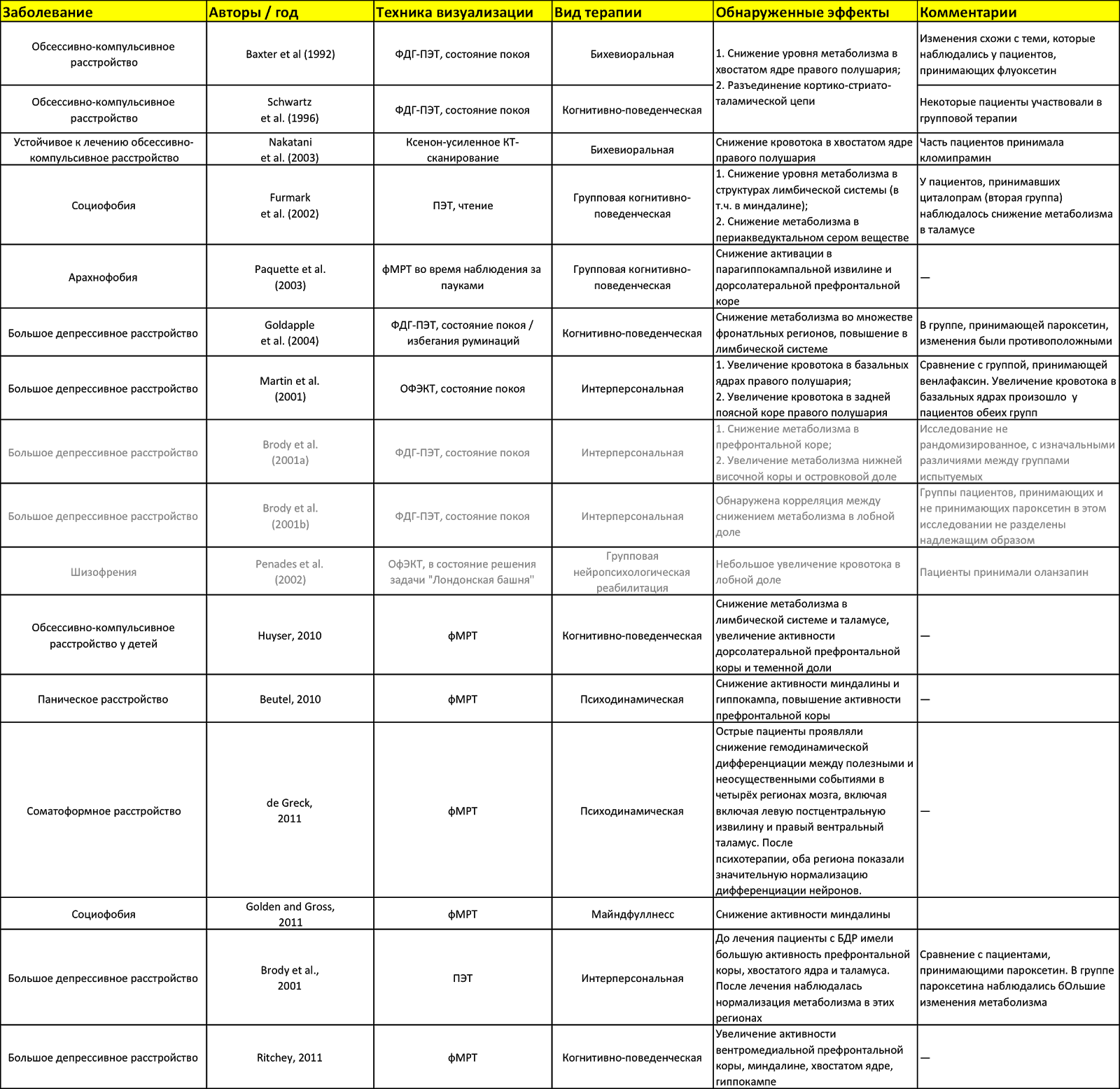

Below is my attempt to systematize the data on the visualization of changes caused in the brain by speaking therapy.

It does not claim to be universal, but when it was created, I tried to include more or less sane studies and recheck the conclusions of the authors.

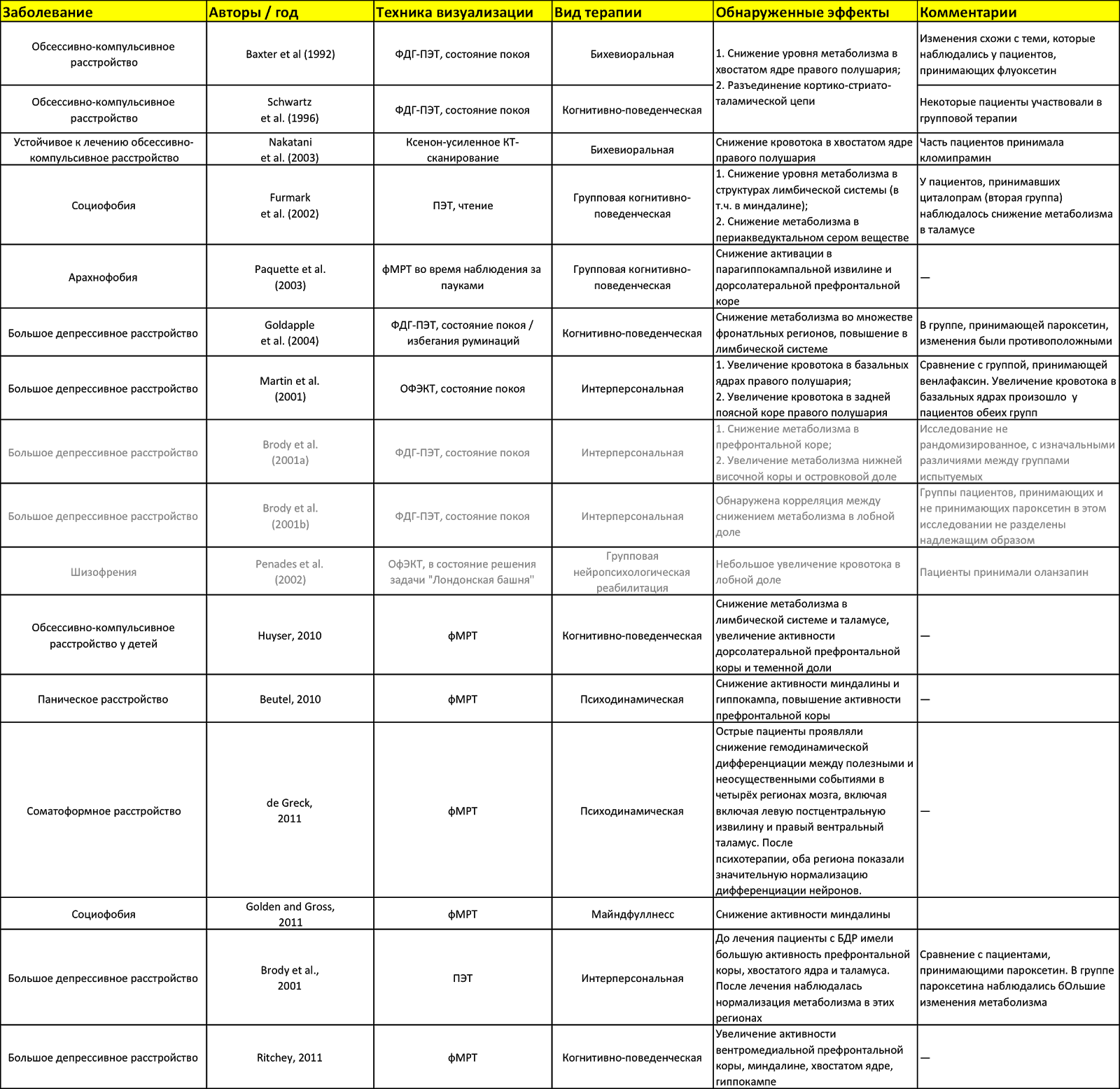

Fig. 4 The effect of speaking therapy on the brain. Sources: [10, 32, 33, 34]. The table is available in Google Docs .

What do we see in this table? The first thing that catches your eye is the fact that the same areas of the brain (for example, the caudate nucleus or the amygdala) are affected by completely different types of therapy.

The second is that in some studies the activity of certain areas increases (for example, the amygdala in the Ritchey study), and in others, with the same therapy, it decreases (the limbic system, including the amygdala, in the study of Goldapple).

The third is that some studies are marked in gray. These are those whose design caused me the greatest doubts. But since there are not so many such studies today, I included them here.

What is the result? Visible some inconsistency data. It is caused by the fact that, firstly, the brain is a complex and controversial thing (I seem to have already spoken about this), and, secondly, by the fact that the research did not have a completely identical methodology.

What is the value of this table, if you can not directly compare different methods of PT? It is possible to make sure that conversational therapy “ does something with the brain there ”, and also that you can try to build some cautious guesses about how this conversational therapy works.

But first, let's try to still highlight some patterns in these changes. To do this, we will not peer into the table for a long time, but use the data from the finished meta-analyzes.

It is assumed that during depression, CPT enhances cortical control from the prefrontal cortex (especially its dorsolateral part), which inhibits (inhibits) impulses of subcortical structures [32, p. 6].

What does this mean: impulses that rise “ from the depths of the unconscious ” (this is just a beautiful metaphor) begin to be better controlled by structures that are more related to rational thinking.

If we recall how KPT works - namely, it tries to replace “ automatic thoughts filled with cognitive distortions with more sober and rationalistic assessments of the situation ”, then we can trace some logic in this whole thing.

Therapy aimed at activating behavior presumably leads to the activation of the striatum and the activation of the reward system, including the regions of the dorsolateral prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex [32, p. 6]

What does this mean: again, the activation of “ more conscious structures ”, as well as structures responsible for behavior (as a set of motor, ie, physical actions).

It is logical: we activated the behavior, activated the structures that are responsible for it. Since this therapy is essentially behaviorism, it is not surprising that the structures responsible are inclusive, incl. for reflexes and analysis of encouragement / punishment.

Overcoming repressed emotions and weakening unconscious guilt, which are important components of psychodynamic therapy , are presumably associated with a decrease in the activity of the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex [32, p. 6].

Everything is quite interesting here, since this very subgenual PPK is involved, including in overcoming feelings of fear (here you can draw far-reaching conclusions that, perhaps, psychodynamics are right, and the repressed guilt is therefore supplanted, because the psyche is “afraid” to accept it, but this will lead us away to speculations).

It should be noted that these assumptions appeared not from scratch, but on the basis of other studies (there are links in [32] on the corresponding pages).

Before discussing the results of research on the effects of conversational therapy on the brain, you need to at least talk a little about how it works, and consider some of its components that are directly related to the subject of the article, in order to understand what the researchers have been doing there.

The main thing that can be said about the brain: it is complex . There are only so many ways to consider it that an unprepared person has a head in a circle - all these columns , departments , cortical maps , functional blocks , Brodmann fields , etc.

Fig. 5 The progress of psychiatry and neuroscience through the eyes of the inhabitant.

We will not try here to examine the structure of the brain from all possible points of view, but only fragmentarily describe those parts of it that are relevant to the subject of this article.

It should be noted that the brain is a distributed system with a high degree of parallelism [21, p. 132], therefore, to say that one or another part of it performs a specific limited function would not be completely wrong. That is why all phrases like (“ amygdala is responsible for fear reactions ” should be perceived as more or less successful analogies / metaphors, nothing more).

However, to some extent its components are specialized, and we will try to consider this specialization in the context we are interested in.

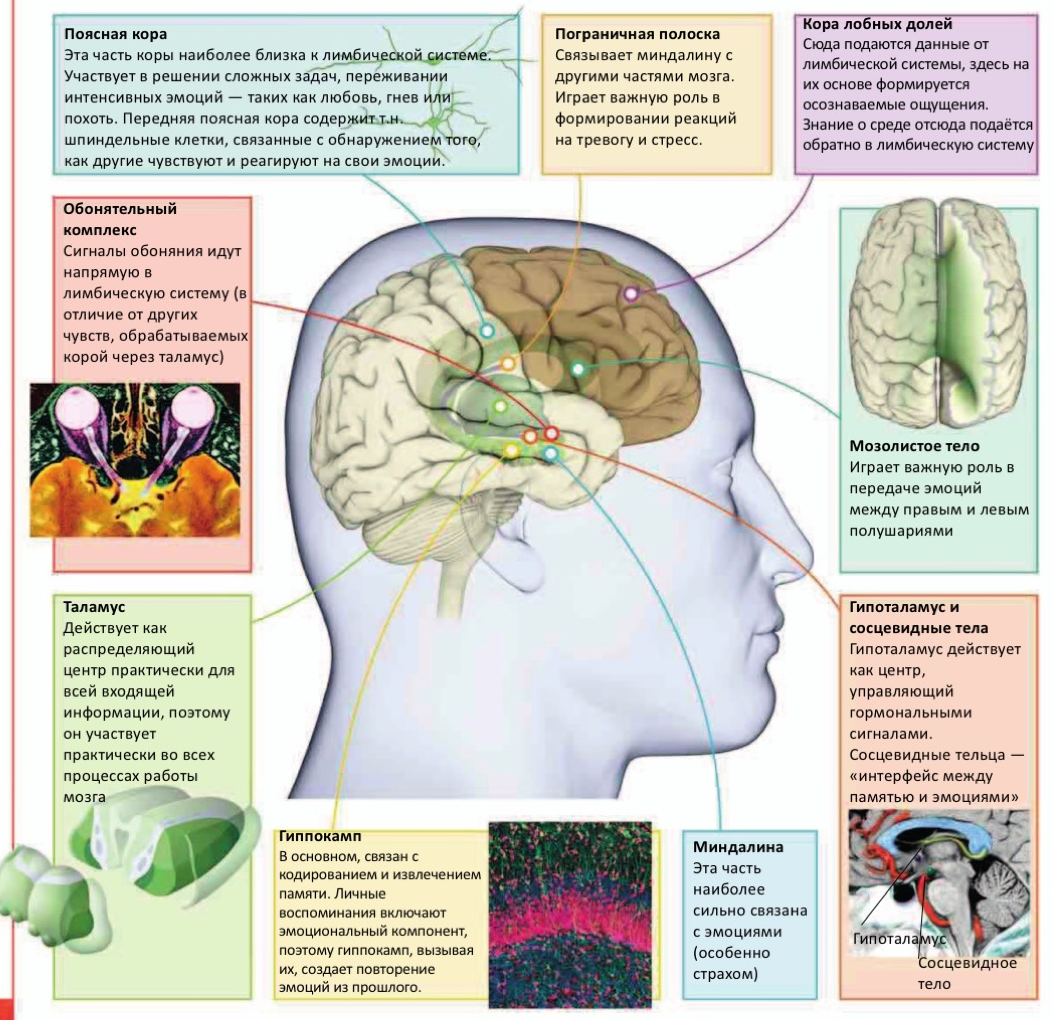

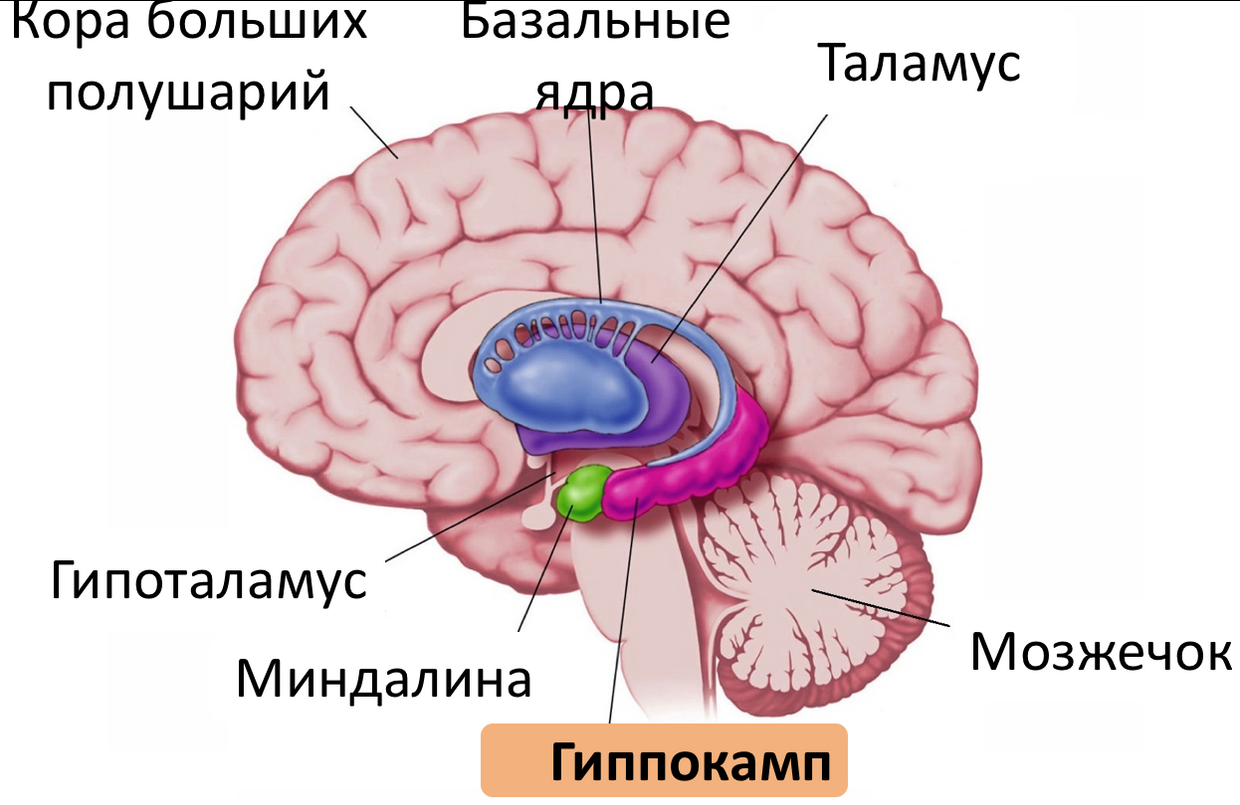

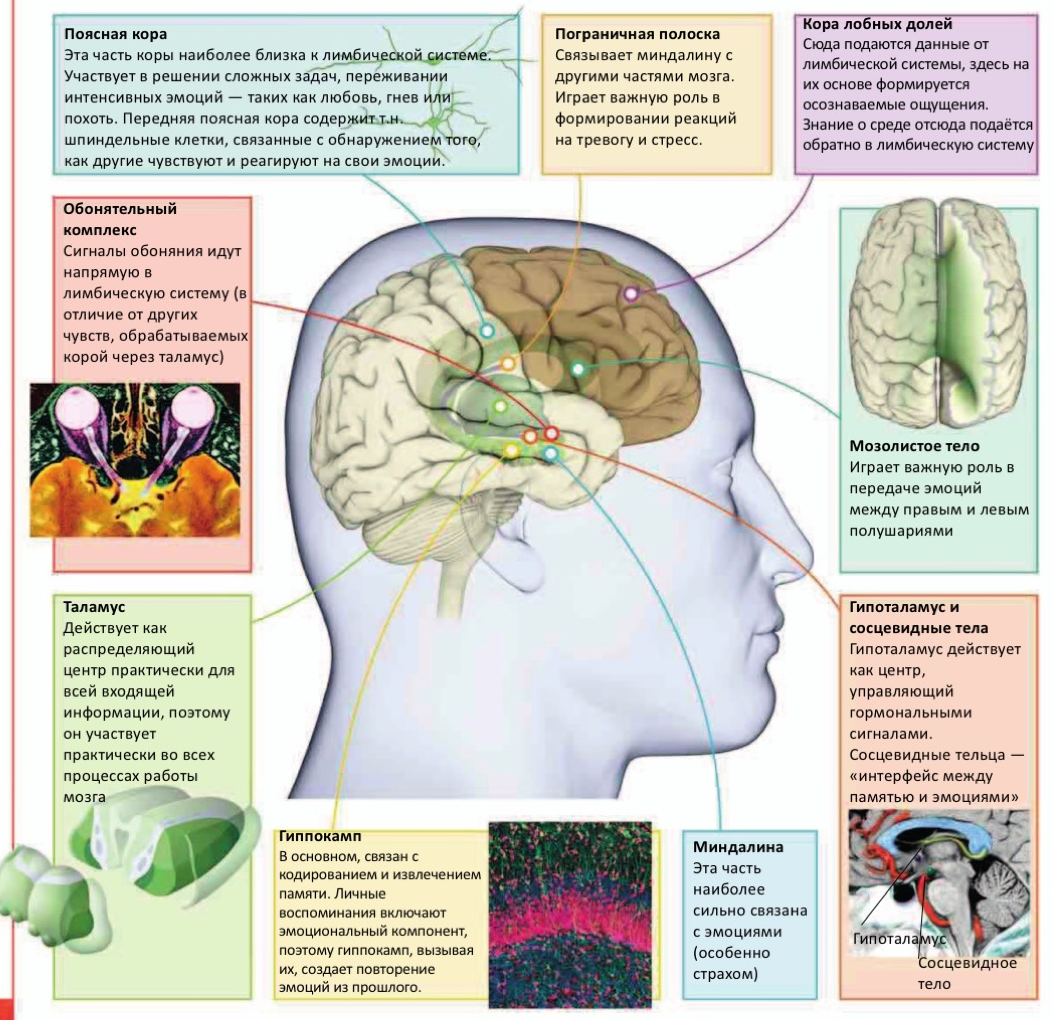

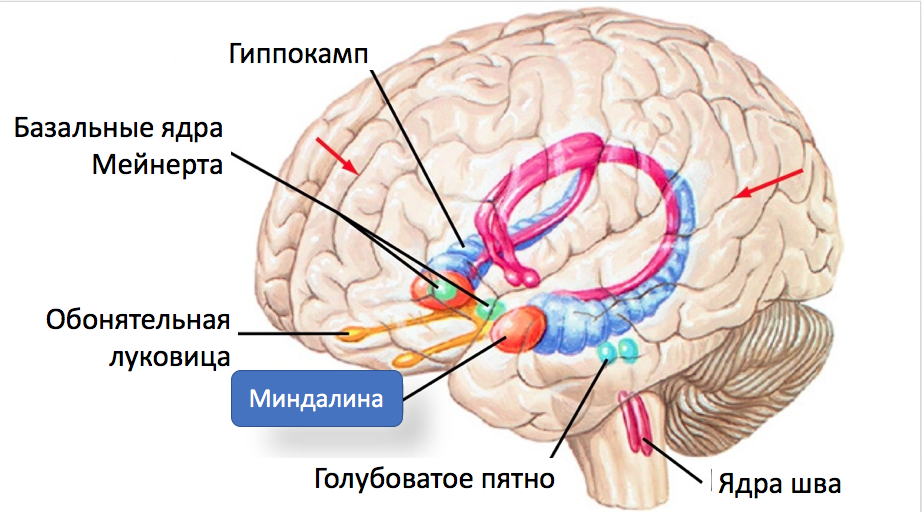

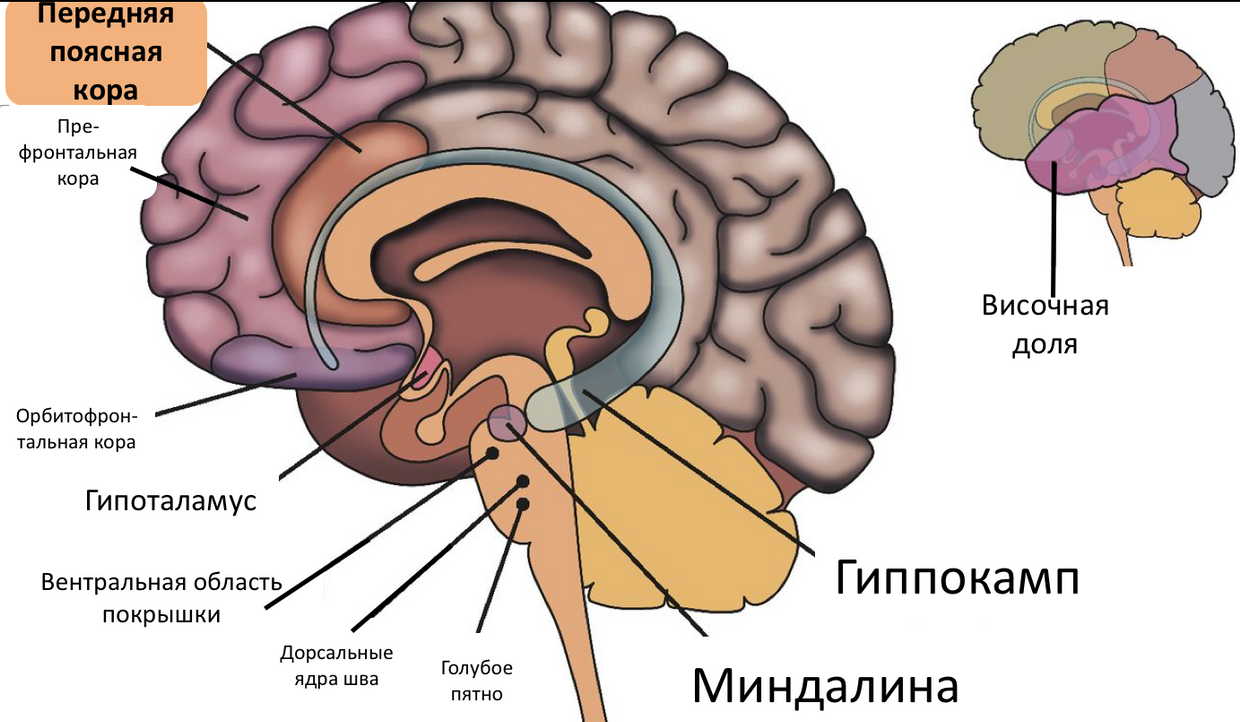

Fig. 6 Some components of the brain relevant to the subject of this article [31, p. 126].

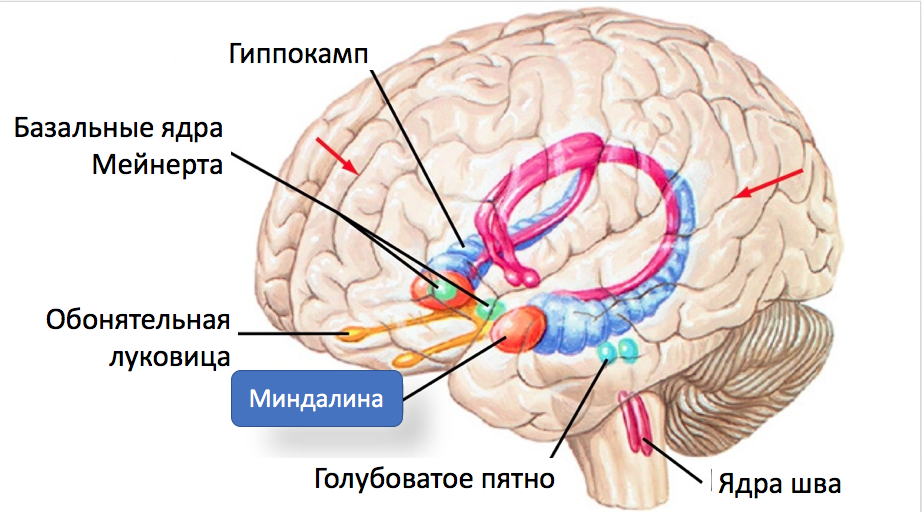

The amygdala, it is also the "almond-shaped body." Located in the temporal lobe (median temporal lobe) [19, p. 232]. Since we have two hemispheres and two temporal lobes, respectively, are also two, the amygdala, as it were, "divides into two pieces." [19, p. 211]. This, by the way, applies not only to the amygdala.

Fig. 7 Tonsil and some of her connections.

Connecting with the prefrontal and temporal cortex , as well as with the spindle-shaped gyrus of the amygdala, plays a significant role in social and emotional cognition [10, p. 240] and is considered the main center for processing emotional information [19, p. 482].

No less important is the fact that the amygdala is connected to the hippocampus [19, p. 216], which is involved in memorizing information (consolidating memory from short-term to long-term), processing and retrieving it from memory [19, p. 78].

Almond is part of the so-called. limbic sistama. It is shown that the structures of the limbic system and the nucleus accumbens participate in the “final reward calculation”, assigning the characteristics of pleasure or displeasure to the affective experience, and the warning / arousal system uses the reticular formation , thalamus, amygdala and cortex to assign personal experience and significance to this experience [ 10, p. 7186].

Studies have shown that the amygdala responds to emotional stimuli [19, p. 297] and mediates the conditioned-reflex reaction of fear [19, p. 538].

The dynamic interactions between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are conceptualized as a system that allows us to automatically respond to biologically significant stimuli, and also to regulate these reactions when the situation requires it [20, p. 113].

The amygdala has two "inputs", through which it receives sensory information. First, data comes from the senses to the thalamus , then they follow one of two independent paths: either directly to the amygdala, or first pass through the prefrontal cortex , and then reach the amygdala through the anterior cingulate cortex [22, p. 19]:

Fig. 8 Two modes of activation of the tonsils.

The first path is “ quick and dirty ” - the amygdala receives information about what kind of tin is created in the outside world, and does not go into details of what exactly this stimulus was: it starts to act, without taking the time to figure out in a situation.

The second way is slower, but involves some analysis of incoming information. The data is processed in the prefrontal cortex , which integrates sensory information from the senses with information about the context of this stimulus received from the hippocampus, compares it with the experience stored in long-term memory, analyzes the previous similar situations and decides how real the danger is. She sends this decision to the amygdala, which, in the case of a positive response, triggers the preparation of the body for the “flight or attack” reaction.

If the cortex " recognized the stimulus as harmless, " the amygdala, on the contrary, inhibits the stress response [22, p. 19].

For example, if an unprepared person noticed a snake in his path, it is highly likely that his amygdala will be activated by the thalamus without the participation of the cortex. At the same time, if this is a gerpentologist who understands that the snake is not dangerous, then, quite possibly, his reaction will follow the second scenario.

It has been shown [10, p. 7184] that the activity of the amygdala is enhanced in depression and post-traumatic disorders . The situation is even worse if an increase in the activity of the amygdala is combined with a decrease in the activity of the prefrontal cortex.

Those. It is beneficial for us to reduce the activity of the amygdala, either directly or indirectly, through increased activity in the prefrontal cortex (see above data on relevant changes as a result of psychotherapy).

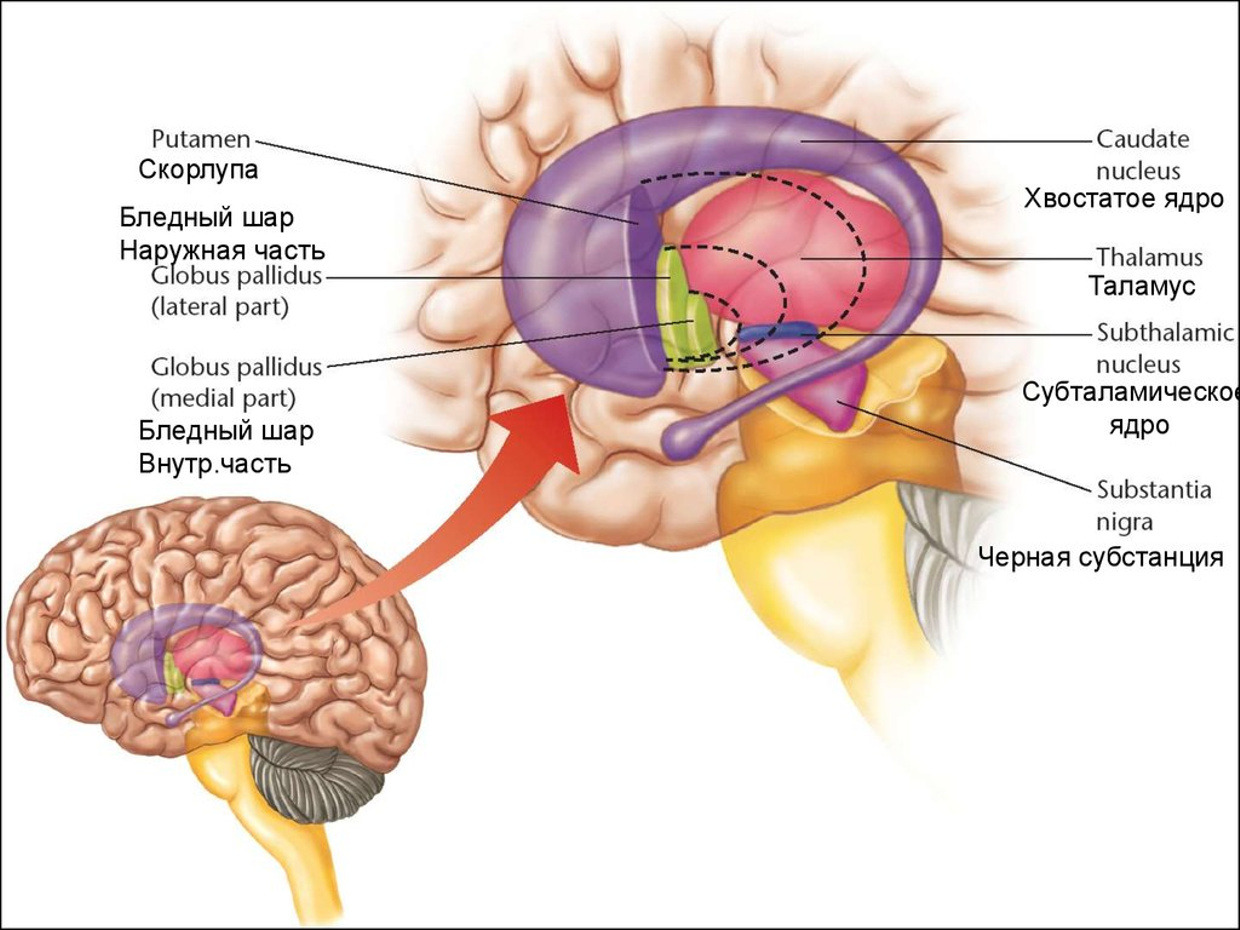

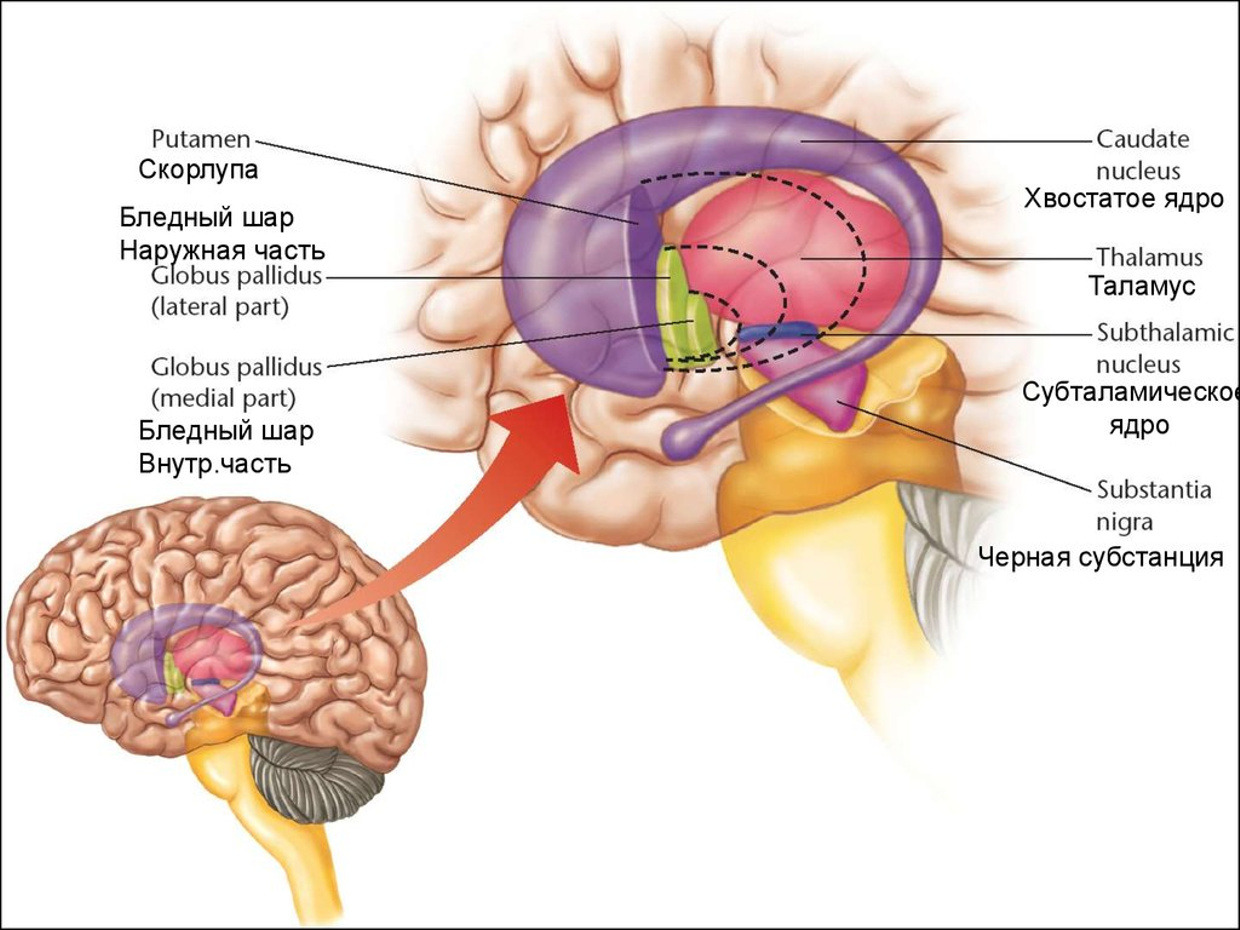

The caudate nucleus (along with the shell-core, which together form the neostriatum ) are part of the basal ganglia , which are connected by afferent (sensory, "incoming") and efferent (motor, "outgoing") connections with the structures of the midbrain - the substantia nigra and subtalamic core .

Fig. 9 Tail core.

The caudate nucleus functions as a part of the “gate” into the basal ganglia, it is associated with the frontal cortex and therefore is involved in high-order cognitive processes. The increased activity of the cortex excites its cells (and the cells of the shell), which, in turn, remove inhibition from the thalamus [23, p. 514].

For our narration, it is important that the tail core contributes to the launch of the correct patterns of actions and the selection of appropriate subgoals based on the assessment of performance results (ie, participates in planning), because Both processes are fundamental to successful, targeted action [24]. Thus, the caudate nucleus can be called the " feedback processor " [31, p. 58]

The ability to perform directed actions is something that often suffers from mental illness.

The caudate nucleus plays an important role in the processes of learning, speech, and the transmission of information about disturbing events between the thalamus and the orbitofrontal cortex.

The increased volume of the caudate nucleus (in comparison with the norm) correlates with impaired spatial working memory [25].

Dysfunction of the caudate nucleus is associated with such phenomena as Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder [38]. In some cases, it makes sense to reduce its activity (more correctly, to return it under the control of the big hemispheres).

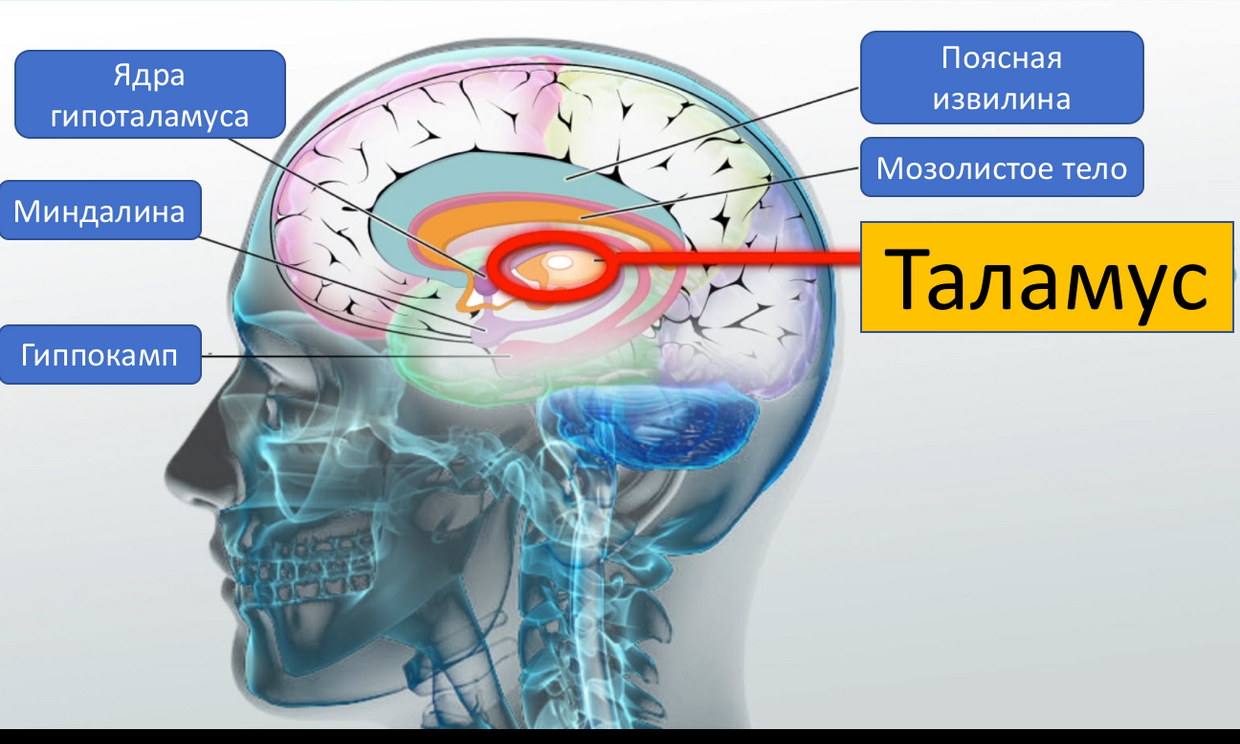

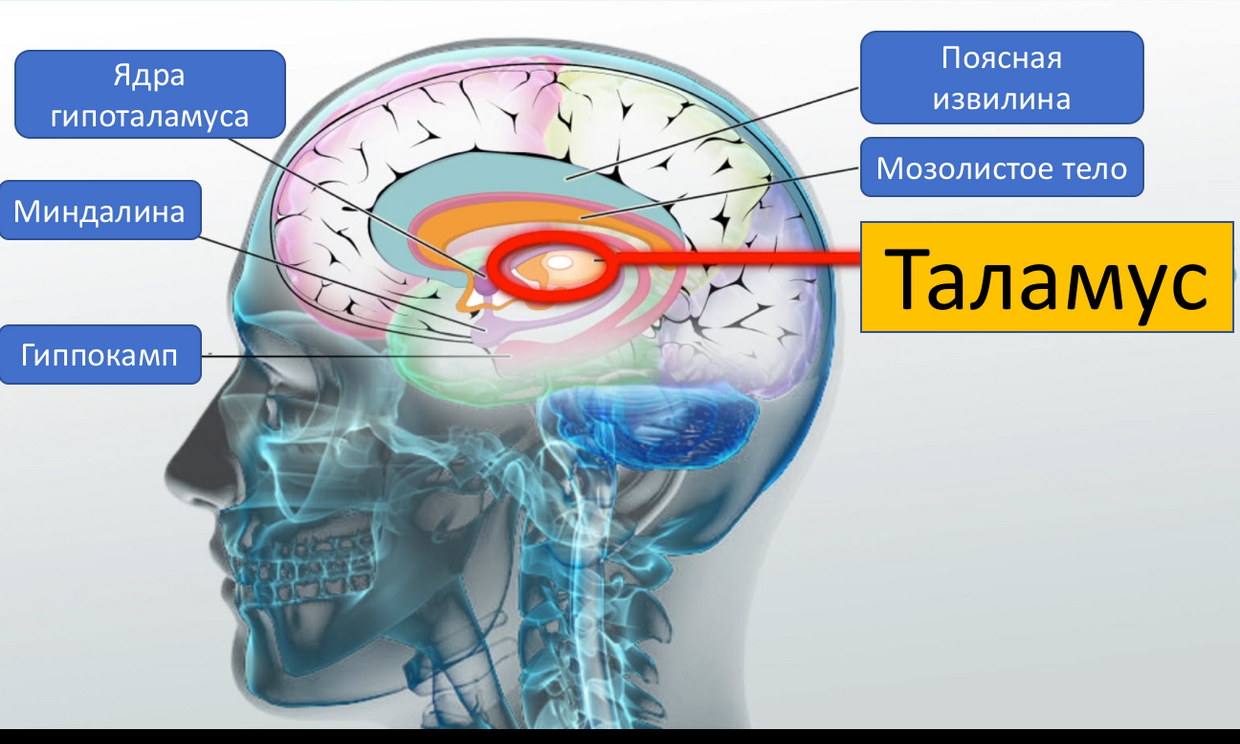

The thalamus (part of the diencephalon) is the most important “neural hub”, where almost all sensory signals (except for the sense of smell) switch to the cortex [19, p. 85].

Fig. 10 Thalamus

The intended function is the reception of information from sensors, its primary processing, input and storage [19, p. 201], transfer to the cortex. In some cases, the thalamus increases the activity of the cortex, in others - it blocks it [19, p. 122]

The fact that olfactory signals bypass the thalamus allows adherents of perfumery and aromatherapy to talk about the importance of their activities with some degree of validity (they say smells can influence the emotional sphere).

Studies on monkeys have shown that the thalamus is associated with compulsive behavior and signs of anxiety [26]. It is believed that the behavior aimed at checking and re-checking, as well as continuous cleaning, is “ sewn ” into the thalamus [27].

Together with the temporal lobes, the thalamus inhibits excessive mood swings that occur in response to complex daily stimuli [10, p. 7185].

The thalamus is a central component for integrating memories of perceptual, somatosensory and cognitive processes [42].

In addition, the thalamus plays an important role in modulating the activity of the amygdala (see above).

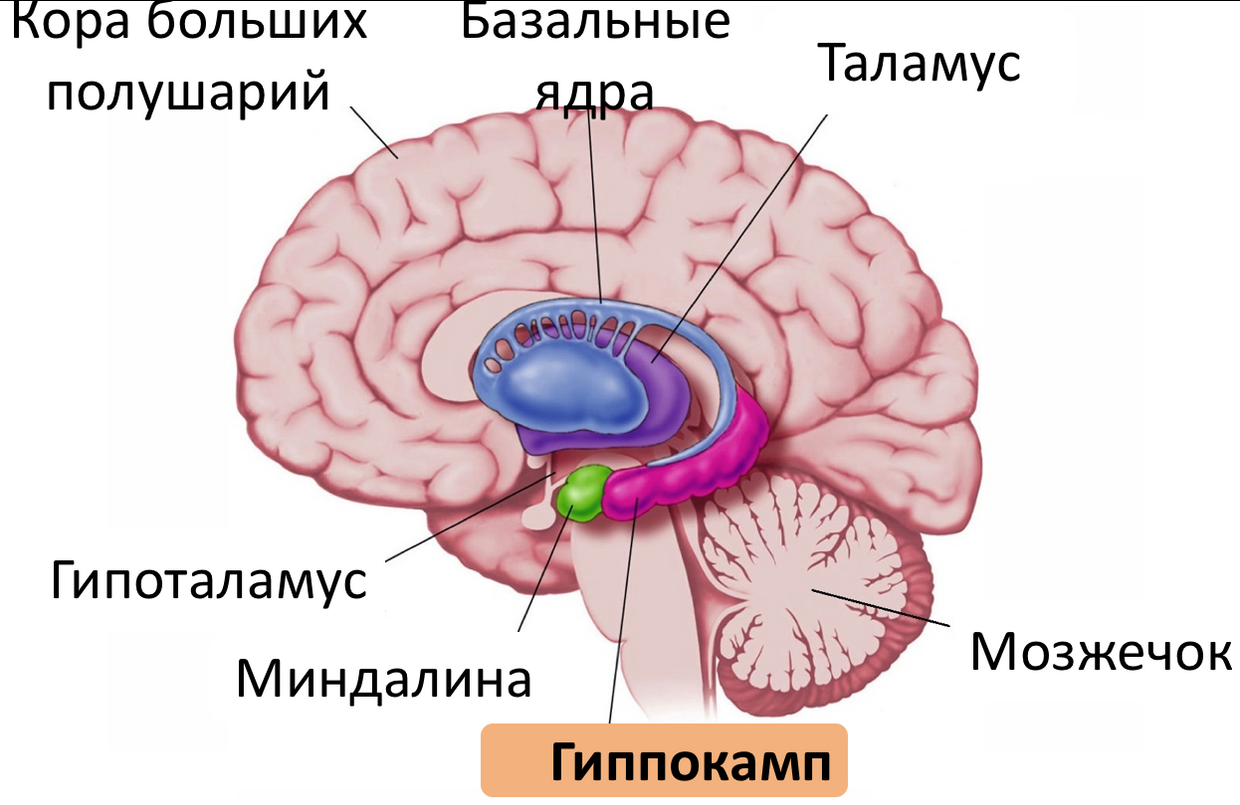

The hippocampus , like the amygdala , is located inside each of the temporal lobes of the brain [19, p. 211].

Fig. 11 Hippocampus.

It plays an important role in the transfer of experimental information to long-term memory, as well as in the extraction of episodic memories, and is related to spatial orientation [19, p. 213].

Studies show that the hippocampus is an important component of the mechanism of consciousness [28]. Hippocampus is one of the few brain structures in which neurogenesis is possible (production of new neurons during life) [19, p. 216]

Together with the amygdala and the limbic cortex, the hippocampus forms the limbic system [19, p. 231]. These structures are closely related to the work of short-term memory (that is, the memory of experience under the control of consciousness) [19, p. 232].

Other studies show that the hippocampus is involved in unconscious memory processes, and that they (conscious and unconscious processes) are interconnected [29] In addition, the hippocampus plays an important role in the processes of spatial imagination, memory formation and access to it [31, p. 65]

The hippocampus (more precisely, its dysfunction) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of such mental diseases as schizophrenia, autism, and depression [10, p. 227].

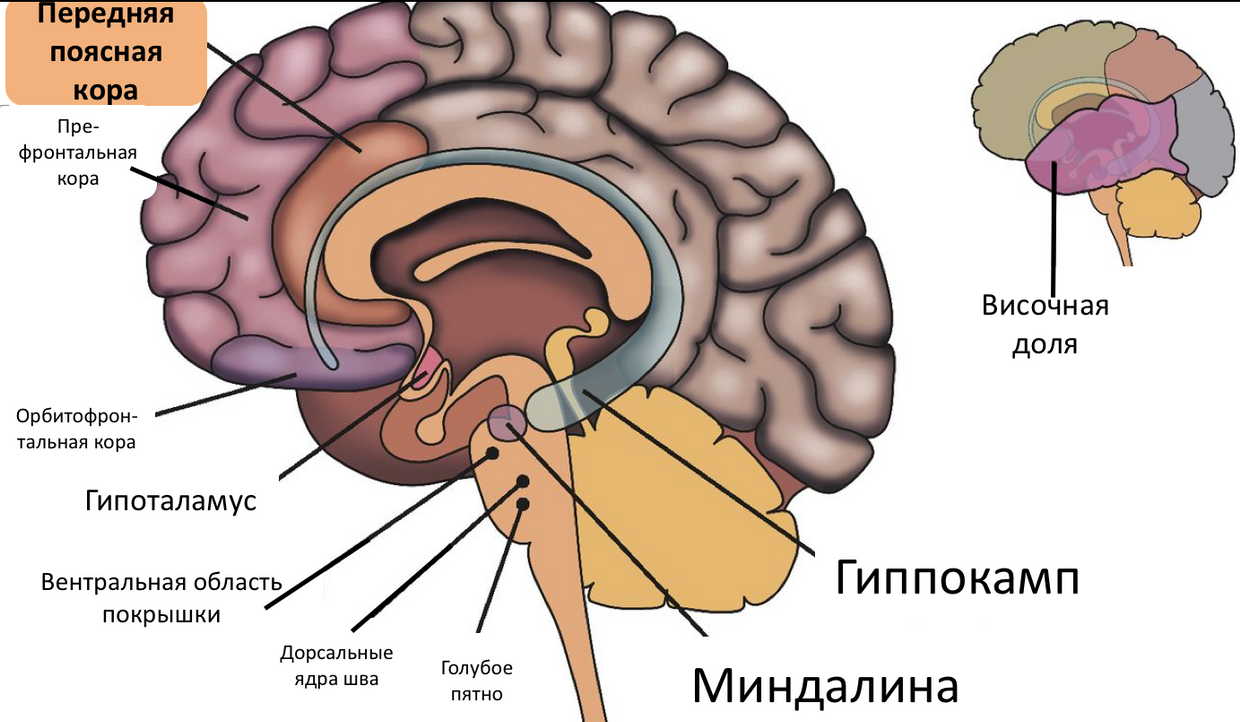

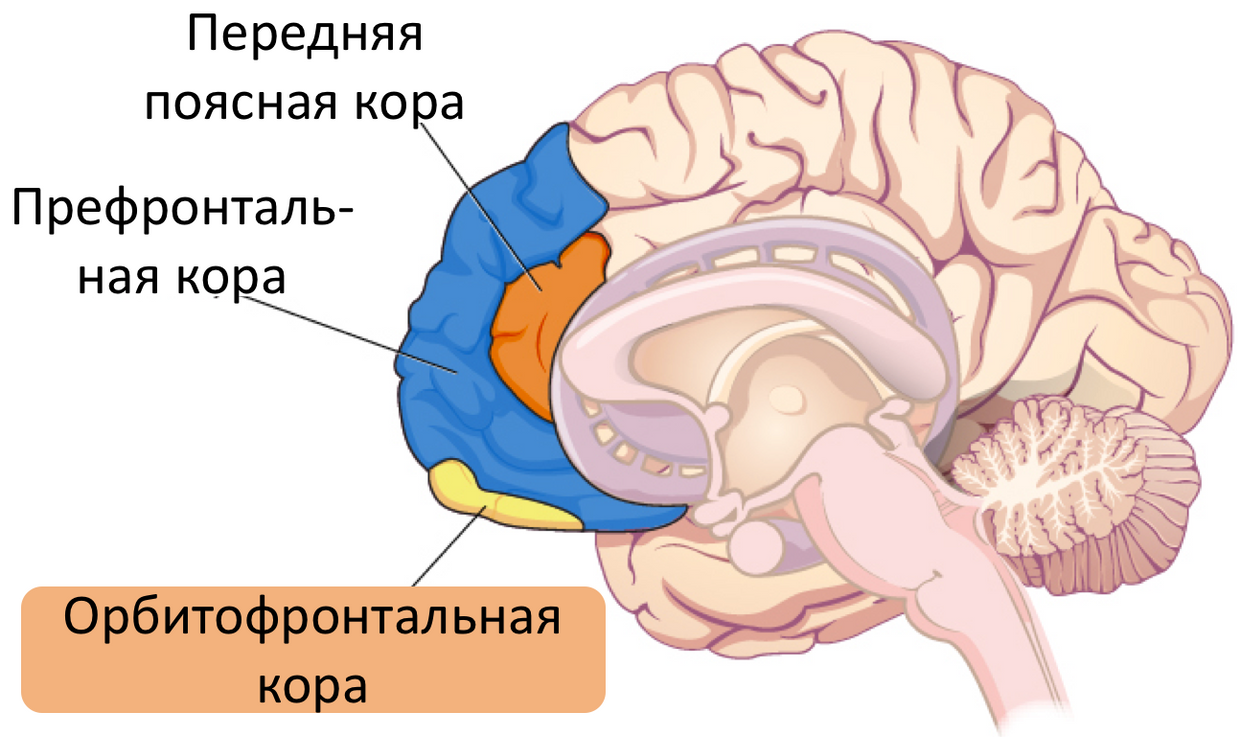

Fig. 12 Anterior cingulate cortex.

The anterior cingulate cortex performs various functions, of which the most interesting for us are [10, p. 7183]: the conscious regulation of emotions through the re-examination of negative emotions, the suppression of excessive arousal and the suppression of the amygdala.

Those. when we understand that we are “ pounding ” in our fears, and we can consciously abandon them, we must say thanks to our anterior cingulate cortex.

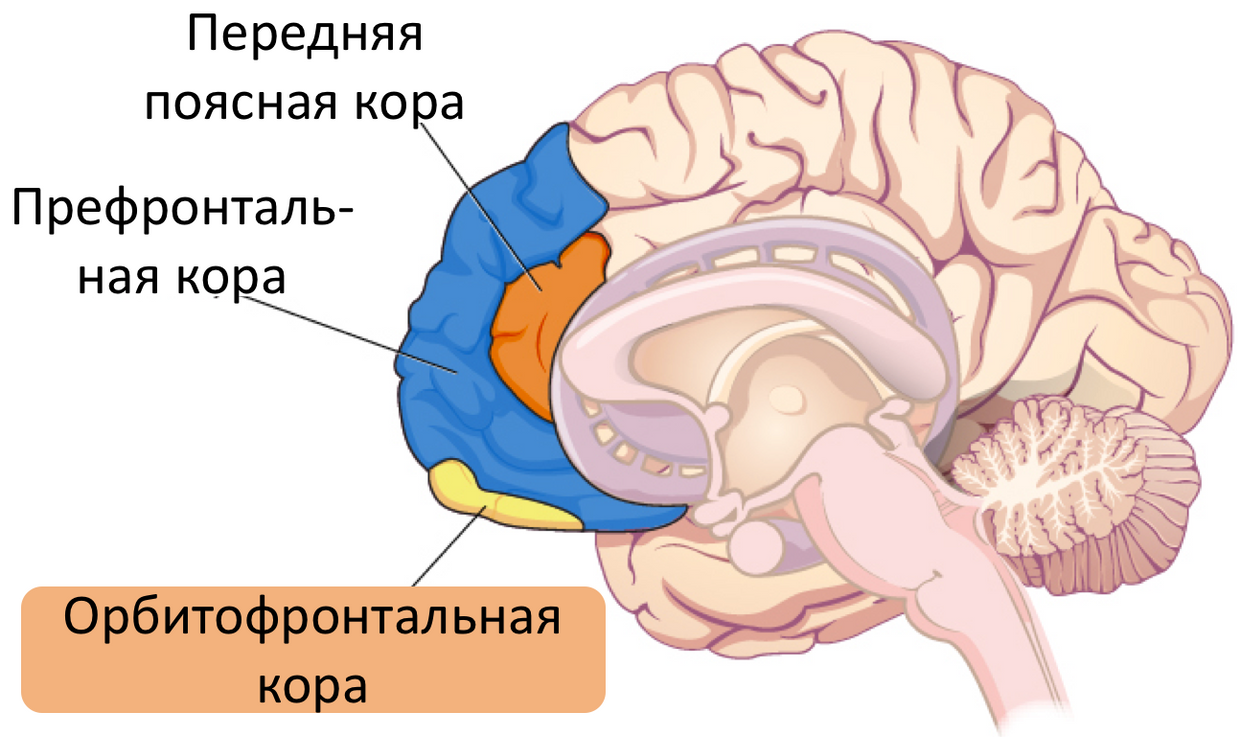

Fig. 13 Prefrontal cortex.

The prefrontal areas of the cortex perform an important control function in the brain. These structures are necessary for arbitrary control. In addition, they participate in emotions and restrain involuntary impulsive reactions [19, p. 93]. Prefrontal cortex involved in the decision-making process related to moral issues [31, p. 7],

Human conscious feelings arise when the signals of the limbic system reach areas of the prefrontal cortex that support consciousness [31, p. 39].

The prefrontal cortex is the substrate for the main functions of the ego [10, p. 7184], together with the amygdala, it controls an essential part of a person’s emotional life and provides adaptability. Disruption of this ligament can cause very acute emotional pain and cloud human prudence.

(.. , “ ” — ) , — . [10, . 7184].

, [10, . 7184] , , , , , « » ( , ).

, , .. , ( ) . .. .

«» , , [31, . 109]

( , , — ) , [10, . 7184]: , , , .

.[32, . 6] , [20, . 115]

, .

Fig. 14 . .

( , ) ( , , ), [10, . 7186]

, , , , , , , [10, . 7186].

[39]. [40] , , : (, ) , , .

- , - , “ ”, .

[35], , , , .

, ( ) . ( ), .

, , [10, . 7185]

[32, . 6]

, , , , [10, . 182].

, [50].

, , , , , , , [10, . 239].

: -- [30].

Insel [36], , : , ( ) : () , .

, , .

Unlike the above nosological units, the early non-maladaptive schemes themselves are not a mental illness: there is no such diagnosis.

However, it makes sense to include them in this article, since they are very widespread in healthy people and significantly hinder them.

What is the early maladaptive scheme (hereinafter - simply “ scheme ”)? A scheme is such a psychic construction that includes memories, thoughts, emotions, and body sensations. And they do not just enter, but in a cunning manner are interconnected and interdependent [48, p. 41].

- ( , , ) ( " , ").

/ .

, , , . , - .

, . .

[48, . 41] . .

: , . , . — , , …

(, - ), . , , , , , ..

, — .

, , , , , .

-[32] ( ), - .

- , , , . .

. Those. “, " - , “”.

. “ ”, “ ” ..

.

— , , . , , ( ).

, , [32, . 18].

- , . , , — ( ).

, , .

[32, . 19]. — “ ” ( , , ), .

-[37] , , , , , , ( ) .

, , , .

[41], , . , , — - .

-[42] ( , , -, ) .

, , , . , .

, / , [44]. .

Well, research quite convincingly shows us that the brain changes under the influence of verbal therapy. But how exactly does he do it?

The answer lies in its property as neuroplasticity. More precisely, not so: there is no direct evidence that psychotherapy increases brain neuroplasticity, but the common place is the idea that this very neuroplasticity is somehow involved in the process of psychotherapy [49].

When applied to the nervous system, neuroplasticity is the ability of nerve elements and regulatory molecules to adaptive reorganization under the influence of endogenous and exogenous influences [46, 79].

Neuroplasticity is observed at different levels [47] - at the level of the brain as a whole, at the level of its individual components, at the level of neurons, and even at the subcellular level.

The fundamental component of neuroplasticity is the plasticity of synaptic connections (ie, connections between neurons), which constantly disappear and reappear, and the balance of these opposite processes depends primarily on the activity of neurons [47].

The dependence of synaptic plasticity on activity is one of the central points of the concept of neuroplasticity, as well as theories of learning and memory, based on changes in the structure and function of synapses caused by experience.

Long-term plasticity is realized as a result of changes in the expression of genes triggered by signaling cascades, which, in turn, are modulated by various signaling molecules with changes in neural activity.

A detailed examination of the molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity is clearly beyond the scope of this article, so we will focus on the fact that the ability of the brain to change under the influence of external influences is proven. And it allows you to implement all those changes, which were discussed above.

Here we will talk about some additional hypotheses about exactly how therapy can affect the brain:

1. Psychotherapy may affect neurotransmitter levels , particularly serotonin . A review [49] showed that patients suffering from bipolar affective disorder and depression and who had lower serotonin levels (compared to the control group) in the prefrontal cortex and thalamus before the start of treatment showed an increase in serotonin levels in these areas after a year’s course of psychodynamic therapy. True, the study on the basis of which this conclusion was made is far from an ideal design (small sample, lack of successful reproduction).

2. Perhaps therapy affects the thyroid axis . The same review [49] refers to a study that showed that depressed patients who responded successfully to CPT achieved a decrease in T4 (thyroid hormone) levels, while patients who did not respond to therapy had it boost

3. Perhaps psychotherapy stimulates processes related to the neuroplasticity of the brain . As mentioned above, there is no clear evidence that psychotherapy leads to an increase in brain neuroplasticity, but there is evidence from animals, according to which training leads to it.

It is believed [49] that in psychotherapy, learning occurs through research , which leads to an increase in the synaptic potentials of the neurons of the perforator path connecting the entorhinal cortex with the dentate gyrus of the hippocampal formation.

The same increase was demonstrated in animal models: rats that had undergone spatial orientation training had a greater density of dendritic spines compared with the two control groups.

Since the length of the dendrites, as well as the structure of their branching, remained unchanged, conclusions were made about the formation of new synapses.

Of course, directly transferring data from animal models to humans, and even taking into account different activities (direct learning in one case and psychotherapy in another) is not entirely correct, but some authors [49] consider it possible to use these data as an argument in the benefit of the hypothesis that psychotherapy changes the brain at the physical level.

Conversational therapy can lead to significant changes in the brain. Naturally, not only is she - various mental exercises, meditation, and life experience in general, also use neuroplasticity to form the corresponding connectome.

However, studies show that during conversational therapy these changes reach a higher level than in its absence.

The question of whether it is possible to use neuroplasticity for self-therapy, I still leave unanswered: the article and so it turned out too long.

And here is the promised video version for those who preferto listen to all garbage in the background on accelerated playback to watch, not read:

Sorry for the quality of the broadcast, it's terrible, I know.

Past my articles were devoted mainly to issues of pharmacology, but this is not really my topic, I am still a clinical psychologist (more recently), so today we will talk about conversational therapy in all its manifestations.

')

tl; dr : in a long and tedious article addresses the issue of the effectiveness of psychotherapy ( yes, effective, within its limits of applicability, of course ), and also provides reflections on how this effectiveness is achieved ( through the implementation of morphological and metabolic changes due to brain neuroplasticity ) .

At the end of the bonus for fans of video format (if there are any): record the presentation on the topic of this article: if you are lazy to read, you can see.

What is psychotherapy

According to the definition adopted by the American Psychological Association, psychotherapy

“This is a deliberate and informed use of clinical [psychological] methods and interpersonal relations, aimed at achieving changes in behavior, thinking, emotional response, and other personal characteristics in a direction that participants consider desirable” [1].

For the purposes of this article, we will not draw a rigid distinction between psychotherapy proper and psychological counseling, which is defined as

“Professional assistance to a person or a group of people in finding ways to resolve or solving a certain difficult or problematic situation of a psychological nature” [2, p. 3]Despite the fact that in the national tradition to emphasize the differences between them is considered good form, some authors recognize the similarity of these practices and group them into the category of " psychological, more precisely, clinical and psychological interventions " [2, p. 3]

In general, as you have already guessed, we will discuss all forms of interaction between the specialist and the client (doctor and patient), when the word effect is used: from classical psychoanalysis to modern behavioral and cognitive-behavioral approaches. Or, to put it more simply, about " talking with a psychologist / psychotherapist ."

Why do you need it when there are pills

Indeed, we live in the 21st century, more and more sophisticated psychiatric drugs intended for the treatment of a little less than all known mental disorders [3] enter the market every year, and the relevance of psychological / psychotherapeutic influences is questioned by many.

However, there are reasons for using conversational (non-drug) methods.

First , they are in some cases just as effective as drug treatment: in the case of depression [4,5], panic disorder , social phobia [5] and even psychosis [6].

Secondly , in some cases they are more effective than drugs: in the treatment of OCD [5], some types of depression [8].

Thirdly , often the joint use of drugs and psychotherapeutic methods is more effective than only drug treatment [6,7,45].

Fourth , in some cases they have fewer side effects and are more easily tolerated [6].

Fig. 2 Treatment with CPT and pharmacotherapy has led to a significant decrease in the activity of the tonsils in situations of anxiety. Source: [45]

Of course, I would not want the reader to have the wrong impression of psychotherapy as a panacea: in some cases, some methods of conversational influence are not only not useful, but also harmful (for example, "unstructured" types of psychotherapy when working with patients with borderline disorder personality ) [9]. Ultimately, the measure of therapeutic effects determines the doctor in each case .

The attentive reader may note that this section is about psychotherapy, but not about psychological counseling.

Indeed, the latter has been studied much worse - both because of the insufficiently developed research methodology ( how to evaluate the success of counseling during a divorce - not by the number of preserved marriages? ), And because of the much smaller prevalence of the principles of "evidence".

What kind of psychotherapy is effective?

There are a great many types of psychotherapy [10]: cognitive , behavioral , cognitive-behavioral , rational-emotive-behavioral , narrative , psychodynamic , psychedelic , interpersonal , gestalt therapy , logotherapy , desensitization and processing by eye movement , etc.

Fig. 3 From the Freudian associations [first level] to modern methods of therapy based on the principles of evidence.

And each school claims to be effective. And in some areas there is quite imputed evidence base. At the same time, in most cases, explanations of this very efficiency are conducted through constructions adopted within the framework of this approach and are not quoted anywhere outside this framework.

For example, logotherapists believe that they achieve positive results by helping the patient find the meaning of life [11], supporters of the cognitive approach - by working with negative automatic thoughts [12], representatives of the psychodynamic direction - by working with the transference, drives and object relations [13], supporters of the psychedelic approach - due to the work with perinatal matrices and systems of condensed experience [14] and so on.

At the same time, the majority of such explanations lose all persuasiveness as soon as they fall outside the context of the theory that generated them. So, for example, the cognitive postulate that thoughts affect emotions [12] is completely unacceptable within the psychodynamic school, where a completely opposite view is used.

Contrary to the opinion prevailing in the domestic environment, proven clinical effectiveness ( to the extent that it complies with the principles of evidence-based medicine that is generally possible for psychotherapy ), it has not only cognitive-behavioral, but also, for example, psychodynamic therapy [15,16,17]. Those. Different therapies based on completely different sets of axioms show comparable effectiveness.

Modern authors note [10, p. 7190] that all approaches to psychotherapy have a common base that ensures efficiency:

“The relationship between therapist and client, in which different roles have a different set of expectations and responsibilities; impartial and unconditional acceptance of the client by the therapist; a union whose goal is to work on common goals. ”However, these categories are too “ hypothetical ” and “ psychological ” (and therefore poorly formalized ) to be satisfied with them as an explanation of the effectiveness of “therapeutic conversations”.

One of the most interesting attempts to isolate and describe quantitatively the universal basis of successful therapy is the study of German authors [18], in which it was found that the predictor of the success of therapy is the difference in emotions that appear on the therapist’s face and those expressed by the client during the narration.

In other words, if during a first session a client with a sad face speaks about his pain (expressing " negative emotion "), and the therapist listens to him, showing interest and satisfaction (" positive emotion "), then the therapy is likely to be successful. If both express emotions of the same direction ("positive" / "negative"), then no.

The authors rather well formalized the testing procedure, having compiled a very limited “vocabulary” of emotions and selecting only those facial expressions that corresponded exactly to it. With regard to determining the success of therapy (also not the easiest task), estimates of the therapist, patient, and objective indicators of symptom reduction were used.

Their conclusions are quite different from the predictions and explanations that psychotherapists themselves give — they talk about anything: about motivational readiness, about the radical of the client’s personality, about the level of organization of that person, about the deep patterns — but not about the emotions that they express with their faces.

Such studies make us somewhat skeptical about the supposed mechanisms for realizing beneficial changes that psychotherapists / psychologists are talking about, and are pushing to find some more convincing ways to explain the existence of these very changes.

Therapy and brain changes

Some time ago, there was no way to objectively evaluate the effect of therapy on the brain, so psychotherapists made the most courageous (and often incorrect) assumptions about the presence and nature of such an effect.

Naturally, this situation could not last forever, and as soon as researchers had available methods for imaging the brain ( PET , MRI , fMRI , SPECT ), studies were published that aimed to determine the extent of the impact (or lack thereof) of conversational therapy on the physiological substrate of the brain .

Identifying this influence would solve several important problems - from proving that conversational therapy works at all , to understanding how it works, whether there is a difference between different types of therapy, etc.

Below is my attempt to systematize the data on the visualization of changes caused in the brain by speaking therapy.

It does not claim to be universal, but when it was created, I tried to include more or less sane studies and recheck the conclusions of the authors.

Fig. 4 The effect of speaking therapy on the brain. Sources: [10, 32, 33, 34]. The table is available in Google Docs .

What do we see in this table? The first thing that catches your eye is the fact that the same areas of the brain (for example, the caudate nucleus or the amygdala) are affected by completely different types of therapy.

The second is that in some studies the activity of certain areas increases (for example, the amygdala in the Ritchey study), and in others, with the same therapy, it decreases (the limbic system, including the amygdala, in the study of Goldapple).

The third is that some studies are marked in gray. These are those whose design caused me the greatest doubts. But since there are not so many such studies today, I included them here.

What is the result? Visible some inconsistency data. It is caused by the fact that, firstly, the brain is a complex and controversial thing (I seem to have already spoken about this), and, secondly, by the fact that the research did not have a completely identical methodology.

What is the value of this table, if you can not directly compare different methods of PT? It is possible to make sure that conversational therapy “ does something with the brain there ”, and also that you can try to build some cautious guesses about how this conversational therapy works.

But first, let's try to still highlight some patterns in these changes. To do this, we will not peer into the table for a long time, but use the data from the finished meta-analyzes.

Assumptions regarding the effect of conversational therapy

It is assumed that during depression, CPT enhances cortical control from the prefrontal cortex (especially its dorsolateral part), which inhibits (inhibits) impulses of subcortical structures [32, p. 6].

What does this mean: impulses that rise “ from the depths of the unconscious ” (this is just a beautiful metaphor) begin to be better controlled by structures that are more related to rational thinking.

If we recall how KPT works - namely, it tries to replace “ automatic thoughts filled with cognitive distortions with more sober and rationalistic assessments of the situation ”, then we can trace some logic in this whole thing.

Therapy aimed at activating behavior presumably leads to the activation of the striatum and the activation of the reward system, including the regions of the dorsolateral prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex [32, p. 6]

What does this mean: again, the activation of “ more conscious structures ”, as well as structures responsible for behavior (as a set of motor, ie, physical actions).

It is logical: we activated the behavior, activated the structures that are responsible for it. Since this therapy is essentially behaviorism, it is not surprising that the structures responsible are inclusive, incl. for reflexes and analysis of encouragement / punishment.

Overcoming repressed emotions and weakening unconscious guilt, which are important components of psychodynamic therapy , are presumably associated with a decrease in the activity of the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex [32, p. 6].

Everything is quite interesting here, since this very subgenual PPK is involved, including in overcoming feelings of fear (here you can draw far-reaching conclusions that, perhaps, psychodynamics are right, and the repressed guilt is therefore supplanted, because the psyche is “afraid” to accept it, but this will lead us away to speculations).

It should be noted that these assumptions appeared not from scratch, but on the basis of other studies (there are links in [32] on the corresponding pages).

Little about the brain

Before discussing the results of research on the effects of conversational therapy on the brain, you need to at least talk a little about how it works, and consider some of its components that are directly related to the subject of the article, in order to understand what the researchers have been doing there.

The main thing that can be said about the brain: it is complex . There are only so many ways to consider it that an unprepared person has a head in a circle - all these columns , departments , cortical maps , functional blocks , Brodmann fields , etc.

Fig. 5 The progress of psychiatry and neuroscience through the eyes of the inhabitant.

We will not try here to examine the structure of the brain from all possible points of view, but only fragmentarily describe those parts of it that are relevant to the subject of this article.

It should be noted that the brain is a distributed system with a high degree of parallelism [21, p. 132], therefore, to say that one or another part of it performs a specific limited function would not be completely wrong. That is why all phrases like (“ amygdala is responsible for fear reactions ” should be perceived as more or less successful analogies / metaphors, nothing more).

However, to some extent its components are specialized, and we will try to consider this specialization in the context we are interested in.

Fig. 6 Some components of the brain relevant to the subject of this article [31, p. 126].

Amygdala

The amygdala, it is also the "almond-shaped body." Located in the temporal lobe (median temporal lobe) [19, p. 232]. Since we have two hemispheres and two temporal lobes, respectively, are also two, the amygdala, as it were, "divides into two pieces." [19, p. 211]. This, by the way, applies not only to the amygdala.

Fig. 7 Tonsil and some of her connections.

Connecting with the prefrontal and temporal cortex , as well as with the spindle-shaped gyrus of the amygdala, plays a significant role in social and emotional cognition [10, p. 240] and is considered the main center for processing emotional information [19, p. 482].

No less important is the fact that the amygdala is connected to the hippocampus [19, p. 216], which is involved in memorizing information (consolidating memory from short-term to long-term), processing and retrieving it from memory [19, p. 78].

Almond is part of the so-called. limbic sistama. It is shown that the structures of the limbic system and the nucleus accumbens participate in the “final reward calculation”, assigning the characteristics of pleasure or displeasure to the affective experience, and the warning / arousal system uses the reticular formation , thalamus, amygdala and cortex to assign personal experience and significance to this experience [ 10, p. 7186].

Studies have shown that the amygdala responds to emotional stimuli [19, p. 297] and mediates the conditioned-reflex reaction of fear [19, p. 538].

The dynamic interactions between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) are conceptualized as a system that allows us to automatically respond to biologically significant stimuli, and also to regulate these reactions when the situation requires it [20, p. 113].

The amygdala has two "inputs", through which it receives sensory information. First, data comes from the senses to the thalamus , then they follow one of two independent paths: either directly to the amygdala, or first pass through the prefrontal cortex , and then reach the amygdala through the anterior cingulate cortex [22, p. 19]:

Fig. 8 Two modes of activation of the tonsils.

The first path is “ quick and dirty ” - the amygdala receives information about what kind of tin is created in the outside world, and does not go into details of what exactly this stimulus was: it starts to act, without taking the time to figure out in a situation.

The second way is slower, but involves some analysis of incoming information. The data is processed in the prefrontal cortex , which integrates sensory information from the senses with information about the context of this stimulus received from the hippocampus, compares it with the experience stored in long-term memory, analyzes the previous similar situations and decides how real the danger is. She sends this decision to the amygdala, which, in the case of a positive response, triggers the preparation of the body for the “flight or attack” reaction.

If the cortex " recognized the stimulus as harmless, " the amygdala, on the contrary, inhibits the stress response [22, p. 19].

For example, if an unprepared person noticed a snake in his path, it is highly likely that his amygdala will be activated by the thalamus without the participation of the cortex. At the same time, if this is a gerpentologist who understands that the snake is not dangerous, then, quite possibly, his reaction will follow the second scenario.

It has been shown [10, p. 7184] that the activity of the amygdala is enhanced in depression and post-traumatic disorders . The situation is even worse if an increase in the activity of the amygdala is combined with a decrease in the activity of the prefrontal cortex.

Those. It is beneficial for us to reduce the activity of the amygdala, either directly or indirectly, through increased activity in the prefrontal cortex (see above data on relevant changes as a result of psychotherapy).

Tail core

The caudate nucleus (along with the shell-core, which together form the neostriatum ) are part of the basal ganglia , which are connected by afferent (sensory, "incoming") and efferent (motor, "outgoing") connections with the structures of the midbrain - the substantia nigra and subtalamic core .

Fig. 9 Tail core.

The caudate nucleus functions as a part of the “gate” into the basal ganglia, it is associated with the frontal cortex and therefore is involved in high-order cognitive processes. The increased activity of the cortex excites its cells (and the cells of the shell), which, in turn, remove inhibition from the thalamus [23, p. 514].

For our narration, it is important that the tail core contributes to the launch of the correct patterns of actions and the selection of appropriate subgoals based on the assessment of performance results (ie, participates in planning), because Both processes are fundamental to successful, targeted action [24]. Thus, the caudate nucleus can be called the " feedback processor " [31, p. 58]

The ability to perform directed actions is something that often suffers from mental illness.

The caudate nucleus plays an important role in the processes of learning, speech, and the transmission of information about disturbing events between the thalamus and the orbitofrontal cortex.

The increased volume of the caudate nucleus (in comparison with the norm) correlates with impaired spatial working memory [25].

Dysfunction of the caudate nucleus is associated with such phenomena as Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder [38]. In some cases, it makes sense to reduce its activity (more correctly, to return it under the control of the big hemispheres).

Thalamus

The thalamus (part of the diencephalon) is the most important “neural hub”, where almost all sensory signals (except for the sense of smell) switch to the cortex [19, p. 85].

Fig. 10 Thalamus

The intended function is the reception of information from sensors, its primary processing, input and storage [19, p. 201], transfer to the cortex. In some cases, the thalamus increases the activity of the cortex, in others - it blocks it [19, p. 122]

The fact that olfactory signals bypass the thalamus allows adherents of perfumery and aromatherapy to talk about the importance of their activities with some degree of validity (they say smells can influence the emotional sphere).

Studies on monkeys have shown that the thalamus is associated with compulsive behavior and signs of anxiety [26]. It is believed that the behavior aimed at checking and re-checking, as well as continuous cleaning, is “ sewn ” into the thalamus [27].

Together with the temporal lobes, the thalamus inhibits excessive mood swings that occur in response to complex daily stimuli [10, p. 7185].

The thalamus is a central component for integrating memories of perceptual, somatosensory and cognitive processes [42].

In addition, the thalamus plays an important role in modulating the activity of the amygdala (see above).

Hippocampus

The hippocampus , like the amygdala , is located inside each of the temporal lobes of the brain [19, p. 211].

Fig. 11 Hippocampus.

It plays an important role in the transfer of experimental information to long-term memory, as well as in the extraction of episodic memories, and is related to spatial orientation [19, p. 213].

Studies show that the hippocampus is an important component of the mechanism of consciousness [28]. Hippocampus is one of the few brain structures in which neurogenesis is possible (production of new neurons during life) [19, p. 216]

Together with the amygdala and the limbic cortex, the hippocampus forms the limbic system [19, p. 231]. These structures are closely related to the work of short-term memory (that is, the memory of experience under the control of consciousness) [19, p. 232].

Other studies show that the hippocampus is involved in unconscious memory processes, and that they (conscious and unconscious processes) are interconnected [29] In addition, the hippocampus plays an important role in the processes of spatial imagination, memory formation and access to it [31, p. 65]

The hippocampus (more precisely, its dysfunction) plays an important role in the pathogenesis of such mental diseases as schizophrenia, autism, and depression [10, p. 227].

Anterior cingulate cortex

Fig. 12 Anterior cingulate cortex.

The anterior cingulate cortex performs various functions, of which the most interesting for us are [10, p. 7183]: the conscious regulation of emotions through the re-examination of negative emotions, the suppression of excessive arousal and the suppression of the amygdala.

Those. when we understand that we are “ pounding ” in our fears, and we can consciously abandon them, we must say thanks to our anterior cingulate cortex.

Prefrontal cortex

Fig. 13 Prefrontal cortex.

The prefrontal areas of the cortex perform an important control function in the brain. These structures are necessary for arbitrary control. In addition, they participate in emotions and restrain involuntary impulsive reactions [19, p. 93]. Prefrontal cortex involved in the decision-making process related to moral issues [31, p. 7],

Human conscious feelings arise when the signals of the limbic system reach areas of the prefrontal cortex that support consciousness [31, p. 39].

The prefrontal cortex is the substrate for the main functions of the ego [10, p. 7184], together with the amygdala, it controls an essential part of a person’s emotional life and provides adaptability. Disruption of this ligament can cause very acute emotional pain and cloud human prudence.

(.. , “ ” — ) , — . [10, . 7184].

, [10, . 7184] , , , , , « » ( , ).

, , .. , ( ) . .. .

«» , , [31, . 109]

( , , — ) , [10, . 7184]: , , , .

.[32, . 6] , [20, . 115]

, .

Fig. 14 . .

( , ) ( , , ), [10, . 7186]

, , , , , , , [10, . 7186].

[39]. [40] , , : (, ) , , .

- , - , “ ”, .

[35], , , , .

, ( ) . ( ), .

Depression

, , [10, . 7185]

[32, . 6]

, , , , [10, . 182].

, [50].

, , , , , , , [10, . 239].

-

: -- [30].

Insel [36], , : , ( ) : () , .

, , .

Unlike the above nosological units, the early non-maladaptive schemes themselves are not a mental illness: there is no such diagnosis.

However, it makes sense to include them in this article, since they are very widespread in healthy people and significantly hinder them.

What is the early maladaptive scheme (hereinafter - simply “ scheme ”)? A scheme is such a psychic construction that includes memories, thoughts, emotions, and body sensations. And they do not just enter, but in a cunning manner are interconnected and interdependent [48, p. 41].

- ( , , ) ( " , ").

/ .

, , , . , - .

, . .

[48, . 41] . .

: , . , . — , , …

(, - ), . , , , , , ..

, — .

, , , , , .

-[32] ( ), - .

- , , , . .

. Those. “, " - , “”.

. “ ”, “ ” ..

.

— , , . , , ( ).

, , [32, . 18].

- , . , , — ( ).

, , .

[32, . 19]. — “ ” ( , , ), .

-[37] , , , , , , ( ) .

, , , .

[41], , . , , — - .

-[42] ( , , -, ) .

, , , . , .

, / , [44]. .

Well, research quite convincingly shows us that the brain changes under the influence of verbal therapy. But how exactly does he do it?

The answer lies in its property as neuroplasticity. More precisely, not so: there is no direct evidence that psychotherapy increases brain neuroplasticity, but the common place is the idea that this very neuroplasticity is somehow involved in the process of psychotherapy [49].

When applied to the nervous system, neuroplasticity is the ability of nerve elements and regulatory molecules to adaptive reorganization under the influence of endogenous and exogenous influences [46, 79].

Neuroplasticity is observed at different levels [47] - at the level of the brain as a whole, at the level of its individual components, at the level of neurons, and even at the subcellular level.

The fundamental component of neuroplasticity is the plasticity of synaptic connections (ie, connections between neurons), which constantly disappear and reappear, and the balance of these opposite processes depends primarily on the activity of neurons [47].

The dependence of synaptic plasticity on activity is one of the central points of the concept of neuroplasticity, as well as theories of learning and memory, based on changes in the structure and function of synapses caused by experience.

Long-term plasticity is realized as a result of changes in the expression of genes triggered by signaling cascades, which, in turn, are modulated by various signaling molecules with changes in neural activity.

A detailed examination of the molecular mechanisms of neuroplasticity is clearly beyond the scope of this article, so we will focus on the fact that the ability of the brain to change under the influence of external influences is proven. And it allows you to implement all those changes, which were discussed above.

Other factors affecting psychotherapy

Here we will talk about some additional hypotheses about exactly how therapy can affect the brain:

1. Psychotherapy may affect neurotransmitter levels , particularly serotonin . A review [49] showed that patients suffering from bipolar affective disorder and depression and who had lower serotonin levels (compared to the control group) in the prefrontal cortex and thalamus before the start of treatment showed an increase in serotonin levels in these areas after a year’s course of psychodynamic therapy. True, the study on the basis of which this conclusion was made is far from an ideal design (small sample, lack of successful reproduction).

2. Perhaps therapy affects the thyroid axis . The same review [49] refers to a study that showed that depressed patients who responded successfully to CPT achieved a decrease in T4 (thyroid hormone) levels, while patients who did not respond to therapy had it boost

3. Perhaps psychotherapy stimulates processes related to the neuroplasticity of the brain . As mentioned above, there is no clear evidence that psychotherapy leads to an increase in brain neuroplasticity, but there is evidence from animals, according to which training leads to it.

It is believed [49] that in psychotherapy, learning occurs through research , which leads to an increase in the synaptic potentials of the neurons of the perforator path connecting the entorhinal cortex with the dentate gyrus of the hippocampal formation.

The same increase was demonstrated in animal models: rats that had undergone spatial orientation training had a greater density of dendritic spines compared with the two control groups.

Since the length of the dendrites, as well as the structure of their branching, remained unchanged, conclusions were made about the formation of new synapses.

Of course, directly transferring data from animal models to humans, and even taking into account different activities (direct learning in one case and psychotherapy in another) is not entirely correct, but some authors [49] consider it possible to use these data as an argument in the benefit of the hypothesis that psychotherapy changes the brain at the physical level.

Practical conclusions

Conversational therapy can lead to significant changes in the brain. Naturally, not only is she - various mental exercises, meditation, and life experience in general, also use neuroplasticity to form the corresponding connectome.

However, studies show that during conversational therapy these changes reach a higher level than in its absence.

The question of whether it is possible to use neuroplasticity for self-therapy, I still leave unanswered: the article and so it turned out too long.

Video version

And here is the promised video version for those who prefer

Sorry for the quality of the broadcast, it's terrible, I know.

Literature

References

1. Recognition of psychotherapy effectiveness: The APA resolution. Campbell, Linda F., Norcross, John C., Vasquez, Melba JT, Kaslow, Nadine J. Psychotherapy, Vol 50 (1), Mar 2013, 98-101. DOI: 10.1037 / a0031817

2. Isurina Galina Lvovna. Psychotherapy and psychological counseling as a type of clinical and psychological intervention // Medical psychology in Russia. 2017. №3.

3. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: the Prescriber's Guide. Stahl, Stephen M. MD, PhD / Softcover / Cambridge University Press / Pub Date 06/17 / 2017 / Edition 06 ISBN: 1316618137 - Subject Class: Pharmacology ISBN-13: 9781316618134

4. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive Therapy vs Moderate to Severe Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62 (4): 409–416. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.62.4.409

5. Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, SL, Andersson, G., Beekman, AT and Reynolds, CF (2013), Theme-analysis of the psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 12: 137-148. doi: 10.1002 / wps.20038

6. Anthony P Morrison, Heather Law, Lucy Carter, Rachel Sellers, Richard Emsley, Melissa Pyle, Paul French, David Shiers, Alison R Yung, Elizabeth K Murphy, Natasha Holden, Ann Steele, Samantha E Bowe, Jasper Palmier-Claus, Victoria Brooks, Rory Byrne, Linda Davies, Peter M Haddad. Antipsychotic drugs versus cognitive behavioral therapy versus a combination of both: a randomized controlled pilot and feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry. VOLUME 5, ISSUE 5, P411-423, MAY 01, 2018. DOI: https: //doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366 (18) 30096-8

7. Sagar V. Parikh, Zindel V. Segal, Sophie Grigoriadis, Arun V. Ravindran, Sidney H. Kennedy, Raymond W. Lam, Scott B. Patten. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Ii. Psychotherapy alone or in combination with antidepressant medication, Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 117, Supplement 1, 2009, Pages S15-S25, ISSN 0165-0327, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.0.042.

8. Siddique J, Chung JY, Brown CH, Miranda J. Minority Women Minority Women With Depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012; 80 (6): 995-1006. doi: 10.1037 / a0030452.

9. John G. Gunderson, MD With Paul S. Links, MD, FRCPC Borderline Personality Disorder. A Clinical Guide, Second Edition, 2008 - 366 pages. ISBN 978-1-58562-335-8

10. Sadock, Benjamin J., Virginia A. Sadock, and Pedro Ruiz. Kaplan & Sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2017. Print.

11. Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006. Print.

12. Beck, Aaron T. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press, 1979. Print.

13. McWilliams, Nancy. Psychoanalytic diagnosis: understanding of the structure in the clinical process. New York: Guilford Press, 2011. Print.

14. Grof, Stanislav, Albert Hofmann, and Andrew Weil. LSD psychotherapy. Ben Lomond, Calif: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, 2008. Print.

15. Falk Leichsenring (2005) Are psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies effective? A review of empirical data, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 86: 3, 841-868, DOI: 10.1516 / RFEE-LKPN-B7TF-KPDU

16. Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65 (2), 98-109. dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018378

17. Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2011). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in complex mental disorders: Update of a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199 (1), 15-22. doi: 10.1192 / bjp.bp.110.082776

18. Thomas Anstadt, Joerg Merten, Burkhard Ullrich & Rainer Krause (1997) Affective Dyadic Behavior, Core Conflictual Relationship Themes, and Psychtherapy Research, 7: 4, 397-417, DOI: 10.1080 / 10503309712331332103

19. Brain, cognition, mind: an introduction to cognitive neuroscience [Electronic resource]: in 2 hours. Part 1 / ed. B. Baarsa, N. Gage; per. from English by ed. prof. V. V. Shulgovsky. - El. ed. - Electron. text given. (1 pdf file: 552 p.). - M .: BINOM. Laboratory of knowledge, 2014. - (The best foreign textbook). - ISBN 978-5-9963-2352-4

20. Brozek, Bartosz, et al. The Emotional Brain Revisited. Place of publication not identified: International Specialized Book Services, 2014. Print.

21. Tryon, Warren W. Cognitive neuroscience and psychotherapy: network principles for a unified theory. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, 2014. Print.

22. Wheat, David & Hassan, Junaid. (2018). Psychiatric Illness: Psychiatric Illness: Psychiatric Illness: A Physiological and Psychological Conceptualization of Panic Disorder (PD).

23. Nicholls John, Martin Robert, Wallas Bruce, Fuchs Paul. From the neuron to the brain. / Per. from English P.M. Balabana, A.V. Galkina, R.A. Giniatullina, R.N. Hazipova, L.S. The surgeon. - M .: Editorial URSS, 2003. - 672 p. color on ISBN: 5-354-00162-5

24. Jessica A. Grahn, John A. Parkinson, Adrian M. Owen, Progress in Neurobiology, Volume 86, Issue 3, 2008, Pages 141-155, ISSN 0301-0082, https: / /doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.09.004.

25. Katrina L. Hannan, Stephen J. Wood, Alison R. Yung, Dennis Velakoulis, Lisa J. Phillips, Bridget Soulsby, Gregor Berger, Patrick D. McGorry, Christos Pantelis, psychosis: A cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study, Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Volume 182, Issue 3, 2010, Pages 223-230, ISSN 0925-4927, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.02. 006.

26. Rotge JY, Aouizerate B, Amestoy V, et al. The associative and limbic thalamus in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: an experimental study in the monkey. Translational Psychiatry. 2012; 2 (9): e161-. doi: 10.1038 / tp.2012.88.

27. ocd.stanford.edu/about/understanding.html

28. Behrendt, Ralf-Peter. “Hippocampus and consciousness” Reviews in the Neurosciences, 24.3 (2013): 239-266. doi: 10.1515 / revneuro-2012-0088

29. Article Source: Hippocampus of Placement of Interaction between Unconscious and Conscious Memories

Züst MA, Colella P, Reber TP, Vuilleumier P, Hauf M, et al. (2015) Hippocampus Place of Interaction between Unconscious and Conscious Memories. PLOS ONE 10 (3): e0122459.https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122459

30. Jeste, Dilip V., and Joseph H. Friedman. Psychiatry for neurologists. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2006. Print.

31. Carter, Rita, et al. The human brain book. New York, New York: DK Publishing, 2014. Print.

32. Sankar, A., Melin, A., Lorenzetti, V., Horton, P., Costafreda, SG, & Fu, CHY (2018). A systematic review and correlation of the theological correction. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 279, 31–39. doi: 10.1016 / j.pscychresns.2018.07.002

33. Brody, AL, Saxena, S., Stoessel, P., Gillies, LA, Fairbanks, LA, Alborzian, S., ... Baxter, LR (2001). Paroxetine or Interpersonal Therapy Regional Brain Metabolic Changes in Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58 (7), 631. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.58.7.631

34. Martin, SD, Martin, E., Rai, SS, Richardson, MA, & Royall, R. (2001). Brain Blood Flowing Changes In Depressed Patients With Interpersonal Psychotherapy Or Venlafaxine Hydrochloride. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58 (7), 641. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.58.7.641

35. Kang DH, Kim JJ, Choi JS, et al. Volumetric investigation of the frontal-subcortical circuitry in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004; 16: 342-349.

36. Insel, TR (1992). Toward a Neuroanatomy of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49 (9), 739. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.1992.0182009006

37. Santos, VA, Carvalho, DD, Van Ameringen, M., Nardi, AE, & Freire, RC (2018). Neuroimaging findings of the outcome of the outcome of psychotherapy in anxiety disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016 / j.pnpbp.2018.04.001

38. Bloch, MH, Leckman, JF, Zhu, H., & Peterson, BS (2005). Caudate volumes in childhood predict symptom severity in adults with Tourette syndrome. Neurology, 65 (8), 1253-12558. doi: 10.1212 / 01.wnl.0000180957.98702.6

39. Antoine Bechara, Hanna Damasio and Antonio R. Damasio. Emotion, Decision Making and the Orbitofrontal Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2000; 10 (3): 295-307.

40. Damasio, A. (1991). Somatic Markers and the Guidance of Behavior. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 217-299.

41. Rubart A, Hohagen F, Zurowski B. [Psychotherapy of the Neurobiological Process - Evidence from Neuroimaging]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2018 Jun; 68 (6) 258-271. doi: 10.1055 / a-0598-4972. PMID: 29864789.

42. Landin-Romero, Ramón & Moreno-Alcazar, Ana & Pagani, Marco & L. Amann, Benedikt. (2018). How Does Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy Work? A Systematic Review on Suggested Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Psychology. 9. 10.3389 / fpsyg.2018.01395.

43. Beutel, ME, Stark, R., Pan, H., Silbersweig, D., & Dietrich, S. (2010). Pre-post short-term psychodynamic inpatient psychotherapy: An fMRI study of panic disorder patients. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 184 (2), 96–104. doi: 10.1016 / j.pscychresns.2010.06.005

44. Buchheim, A., Viviani, R., Kessler, H., Kächele, H., Cierpka, M., Roth, G., ... Taubner, S. (2012). Changes in Prefrontal-Limbic Function in Major Depression after 15 Months of Long-Term Psychotherapy. PLoS ONE, 7 (3), e33745. doi: 10.1371 / journal.pone.0033745

45. Etkin, A., Pittenger, C., Polan, HJ, & Kandel, ER (2005). Toward a Neurobiology of Psychotherapy: Basic Science and Clinical Applications. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 17 (2), 145–158. doi: 10.1176 / jnp.17.2.145

46. Oleg Gomazkov. Neurogenesis as an adaptive function of the brain. INSTITUTE OF BIOMEDICAL CHEMISTRY NAMED AFTER VN OREKHOVICH. M .: 2014.

47. N.V. Gulyaeva. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF NEUROPLASTICITY: THE EXPANDING UNIVERSE. BIOCHEMISTRY, 2017, volume 82, no. 3, s. 365 - 371

48. Young, Jeffrey E., Janet S. Klosko, and Marjorie E. Weishaar. Schema therapy: a practitioner's guide. New York: Guilford Press, 2003. Print.

49. Liggan, Deborah Y., and Jerald Kay. “Some Neurobiological Aspects of Psychotherapy: A Review.” The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 8.2 (1999): 103–114. Print.

50. Arnone, D., McIntosh, AM, Ebmeier, KP, Munafò, MR, & Anderson, IM (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging studies in unipolar depression: systematic review and meta-regression analyzes. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 22 (1), 1–16. doi: 10.1016 / j.euroneuro.2011.05.003

2. Isurina Galina Lvovna. Psychotherapy and psychological counseling as a type of clinical and psychological intervention // Medical psychology in Russia. 2017. №3.

3. Stahl's Essential Psychopharmacology: the Prescriber's Guide. Stahl, Stephen M. MD, PhD / Softcover / Cambridge University Press / Pub Date 06/17 / 2017 / Edition 06 ISBN: 1316618137 - Subject Class: Pharmacology ISBN-13: 9781316618134

4. DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, et al. Cognitive Therapy vs Moderate to Severe Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005; 62 (4): 409–416. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.62.4.409

5. Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, SL, Andersson, G., Beekman, AT and Reynolds, CF (2013), Theme-analysis of the psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy direct comparisons. World Psychiatry 12: 137-148. doi: 10.1002 / wps.20038

6. Anthony P Morrison, Heather Law, Lucy Carter, Rachel Sellers, Richard Emsley, Melissa Pyle, Paul French, David Shiers, Alison R Yung, Elizabeth K Murphy, Natasha Holden, Ann Steele, Samantha E Bowe, Jasper Palmier-Claus, Victoria Brooks, Rory Byrne, Linda Davies, Peter M Haddad. Antipsychotic drugs versus cognitive behavioral therapy versus a combination of both: a randomized controlled pilot and feasibility study. The Lancet Psychiatry. VOLUME 5, ISSUE 5, P411-423, MAY 01, 2018. DOI: https: //doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366 (18) 30096-8

7. Sagar V. Parikh, Zindel V. Segal, Sophie Grigoriadis, Arun V. Ravindran, Sidney H. Kennedy, Raymond W. Lam, Scott B. Patten. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Ii. Psychotherapy alone or in combination with antidepressant medication, Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 117, Supplement 1, 2009, Pages S15-S25, ISSN 0165-0327, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.0.042.

8. Siddique J, Chung JY, Brown CH, Miranda J. Minority Women Minority Women With Depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2012; 80 (6): 995-1006. doi: 10.1037 / a0030452.

9. John G. Gunderson, MD With Paul S. Links, MD, FRCPC Borderline Personality Disorder. A Clinical Guide, Second Edition, 2008 - 366 pages. ISBN 978-1-58562-335-8

10. Sadock, Benjamin J., Virginia A. Sadock, and Pedro Ruiz. Kaplan & Sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, 2017. Print.

11. Frankl, Viktor E. Man’s search for meaning. Boston: Beacon Press, 2006. Print.

12. Beck, Aaron T. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press, 1979. Print.

13. McWilliams, Nancy. Psychoanalytic diagnosis: understanding of the structure in the clinical process. New York: Guilford Press, 2011. Print.

14. Grof, Stanislav, Albert Hofmann, and Andrew Weil. LSD psychotherapy. Ben Lomond, Calif: Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, 2008. Print.

15. Falk Leichsenring (2005) Are psychodynamic and psychoanalytic therapies effective? A review of empirical data, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 86: 3, 841-868, DOI: 10.1516 / RFEE-LKPN-B7TF-KPDU

16. Shedler, J. (2010). The efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 65 (2), 98-109. dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018378

17. Leichsenring, F., & Rabung, S. (2011). Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy in complex mental disorders: Update of a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199 (1), 15-22. doi: 10.1192 / bjp.bp.110.082776

18. Thomas Anstadt, Joerg Merten, Burkhard Ullrich & Rainer Krause (1997) Affective Dyadic Behavior, Core Conflictual Relationship Themes, and Psychtherapy Research, 7: 4, 397-417, DOI: 10.1080 / 10503309712331332103

19. Brain, cognition, mind: an introduction to cognitive neuroscience [Electronic resource]: in 2 hours. Part 1 / ed. B. Baarsa, N. Gage; per. from English by ed. prof. V. V. Shulgovsky. - El. ed. - Electron. text given. (1 pdf file: 552 p.). - M .: BINOM. Laboratory of knowledge, 2014. - (The best foreign textbook). - ISBN 978-5-9963-2352-4

20. Brozek, Bartosz, et al. The Emotional Brain Revisited. Place of publication not identified: International Specialized Book Services, 2014. Print.

21. Tryon, Warren W. Cognitive neuroscience and psychotherapy: network principles for a unified theory. Amsterdam: Elsevier Academic Press, 2014. Print.

22. Wheat, David & Hassan, Junaid. (2018). Psychiatric Illness: Psychiatric Illness: Psychiatric Illness: A Physiological and Psychological Conceptualization of Panic Disorder (PD).

23. Nicholls John, Martin Robert, Wallas Bruce, Fuchs Paul. From the neuron to the brain. / Per. from English P.M. Balabana, A.V. Galkina, R.A. Giniatullina, R.N. Hazipova, L.S. The surgeon. - M .: Editorial URSS, 2003. - 672 p. color on ISBN: 5-354-00162-5

24. Jessica A. Grahn, John A. Parkinson, Adrian M. Owen, Progress in Neurobiology, Volume 86, Issue 3, 2008, Pages 141-155, ISSN 0301-0082, https: / /doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.09.004.

25. Katrina L. Hannan, Stephen J. Wood, Alison R. Yung, Dennis Velakoulis, Lisa J. Phillips, Bridget Soulsby, Gregor Berger, Patrick D. McGorry, Christos Pantelis, psychosis: A cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study, Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, Volume 182, Issue 3, 2010, Pages 223-230, ISSN 0925-4927, https: //doi.org/10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.02. 006.

26. Rotge JY, Aouizerate B, Amestoy V, et al. The associative and limbic thalamus in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder: an experimental study in the monkey. Translational Psychiatry. 2012; 2 (9): e161-. doi: 10.1038 / tp.2012.88.

27. ocd.stanford.edu/about/understanding.html

28. Behrendt, Ralf-Peter. “Hippocampus and consciousness” Reviews in the Neurosciences, 24.3 (2013): 239-266. doi: 10.1515 / revneuro-2012-0088

29. Article Source: Hippocampus of Placement of Interaction between Unconscious and Conscious Memories

Züst MA, Colella P, Reber TP, Vuilleumier P, Hauf M, et al. (2015) Hippocampus Place of Interaction between Unconscious and Conscious Memories. PLOS ONE 10 (3): e0122459.https: //doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122459

30. Jeste, Dilip V., and Joseph H. Friedman. Psychiatry for neurologists. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, 2006. Print.

31. Carter, Rita, et al. The human brain book. New York, New York: DK Publishing, 2014. Print.

32. Sankar, A., Melin, A., Lorenzetti, V., Horton, P., Costafreda, SG, & Fu, CHY (2018). A systematic review and correlation of the theological correction. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 279, 31–39. doi: 10.1016 / j.pscychresns.2018.07.002

33. Brody, AL, Saxena, S., Stoessel, P., Gillies, LA, Fairbanks, LA, Alborzian, S., ... Baxter, LR (2001). Paroxetine or Interpersonal Therapy Regional Brain Metabolic Changes in Patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58 (7), 631. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.58.7.631

34. Martin, SD, Martin, E., Rai, SS, Richardson, MA, & Royall, R. (2001). Brain Blood Flowing Changes In Depressed Patients With Interpersonal Psychotherapy Or Venlafaxine Hydrochloride. Archives of General Psychiatry, 58 (7), 641. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.58.7.641

35. Kang DH, Kim JJ, Choi JS, et al. Volumetric investigation of the frontal-subcortical circuitry in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004; 16: 342-349.

36. Insel, TR (1992). Toward a Neuroanatomy of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 49 (9), 739. doi: 10.1001 / archpsyc.1992.0182009006

37. Santos, VA, Carvalho, DD, Van Ameringen, M., Nardi, AE, & Freire, RC (2018). Neuroimaging findings of the outcome of the outcome of psychotherapy in anxiety disorders. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. doi: 10.1016 / j.pnpbp.2018.04.001

38. Bloch, MH, Leckman, JF, Zhu, H., & Peterson, BS (2005). Caudate volumes in childhood predict symptom severity in adults with Tourette syndrome. Neurology, 65 (8), 1253-12558. doi: 10.1212 / 01.wnl.0000180957.98702.6

39. Antoine Bechara, Hanna Damasio and Antonio R. Damasio. Emotion, Decision Making and the Orbitofrontal Cortex. Cereb Cortex 2000; 10 (3): 295-307.

40. Damasio, A. (1991). Somatic Markers and the Guidance of Behavior. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 217-299.

41. Rubart A, Hohagen F, Zurowski B. [Psychotherapy of the Neurobiological Process - Evidence from Neuroimaging]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2018 Jun; 68 (6) 258-271. doi: 10.1055 / a-0598-4972. PMID: 29864789.

42. Landin-Romero, Ramón & Moreno-Alcazar, Ana & Pagani, Marco & L. Amann, Benedikt. (2018). How Does Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy Work? A Systematic Review on Suggested Mechanisms of Action. Frontiers in Psychology. 9. 10.3389 / fpsyg.2018.01395.