Rome Club Report 2018, Chapter 3.7: “Climate: good news, but big problems”

I propose to deal with the report of the “world government” themselves, and at the same time help you translate the original source.

As already emphasized in Ch. 1, the world must undergo a quick and thorough transformation of its production and consumption systems in order to be able to stay within the “2 ° target”. Only the Paris Agreement and the measures taken by governments, far from reaching the goal. Instead of maintaining warming below 2 ° degrees, the world is on a path of 3 ° or more degrees. Heating the Earth by 2 ° (Celsius) is not only slightly worse than 1.0-1.3 ° (or so), we have already warmed it; it is much more dangerous. Three degrees is much more dangerous. Four means living on a frightening, chaotic planet, the like of which humans have never experienced.

So, the situation is critical. But let's start with the good news.

')

In paragraph 3.4, the exciting trend of a decentralized energy system was noted, starting with a quote from Amory Lovins: “Imagine fuel without fear. Without climate change ... ". The chapter says that over the past 10-20 years, renewable energy sources are becoming cheaper, and in the meantime, new coal and nuclear installations are losing ground. Figure 3.6 shows a seemingly fatal decline in the Dow Jones US Coal Index. Investors are switching to renewable energy sources.

The associated development provides additional grounds for hope: a widespread and global campaign for alienation, which was mainly driven by climate issues. By March 2017, 701 organizations, representing $ 5.46 trillion, had sold their shares of fossil fuel companies. It was the fastest growing movement to withdraw investment in history.

Accelerating the debate about "stuck assets" is another sign that change is in the air. As Alex Steffen writes in his blog (March 2017), “Fuel that cannot be burned does not cost much. In turn, companies whose main assets are in coal, oil and gas cost much less than their stock prices. The difference between the estimates of fossil fuel companies and their true value is so great that national banks, financial industries, associations and respected investors from all over the world warn that it represents a bubble potentially like the 2007 mortgage crisis. ”

For example, according to Barclays Bank estimates, limiting emissions to 2 ° C will reduce the future revenues of the oil, coal and gas industry by $ 33 trillion over the next 25 years. In January 2017, the Bank of England published a document in which it stated that the carbon bubble rupture was likely to be sharp and "likely to create risks for financial stability."

The price of something is that you can get someone to pay for it. For investors owning coal, oil and gas companies, supporting the view that these companies will be profitable in the future, is now a priority of several trillion dollars. This, by the way, seems to be one of the things that unites Trump and Putin. Both are genuinely interested in keeping the value of fossil assets at the highest possible level.

Another related issue is CO2 emissions from transport. But there is good news here, reports the Carbon Tracker Initiative and the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London. In essence, the presented scenarios suggest a sharp rise in solar electricity (PV, photovoltaic energy) and, in parallel, electric vehicles. If this happens, it is likely that the growth in world oil demand will stop already from 2020 and beyond and will lead to the depletion of fossil fuel reserves as the low carbon transition accelerates. The result may be more or less carbon-free mobility in a few decades. But this, of course, depends on the phase-out of coal as the main fuel for electricity generation.

In Section 3.9, evidence of the enormous potential for energy savings will be considered. It is possible to increase energy efficiency by a factor of five, which will drastically reduce the need for energy supply. However, to establish commercial profitability will require some major changes to the framework conditions, as discussed in section 3.10.

More other good news comes from another region. It was mainly a nine-year-old German boy, Felix Finkbeiner, who in 2007 began thinking about a big tree planting. After learning of the threats of global warming and hearing how Wangari Maathai and the green belt movement planted 30 million trees in Kenya, Felix argued that the children of the world could join in and plant many more trees. In the same year, the “plant for the planet” initiative was established, starting with the commitment to plant one million trees in each country of the world.

Movement grew faster than expected. They organized “academies” for children aged 8-14 years, giving them the opportunity to become ambassadors for climate justice. By 2016, 51,000 children from 193 countries received this title. The goal of the movement today is for every citizen of the world to plant 150 trees on average in order to reach 1000 billion trees by 2020. This would help absorb a significant portion of CO2 emissions.

Another impetus for action to combat climate change is the link with agriculture, as described in section 3.5. Soil restoration to high fertility is obviously useful for high yields of agricultural crops. But it also greatly increases the ability of soils to absorb CO2 (see also Section. 3.1.4). This means that the task of feeding the 7.5 billion people in the world should not conflict with the objectives of the climate policy, with the proviso that the number of livestock should be reduced rather than increased due to methane emissions from animal digestion.

The Treaty of Paris is a call to action for all governments in the world. However, the necessary changes must begin in industrialized countries. They have built their standard of living on cheap oil and gas and are obliged to lead the developing world.

Of course, industrialized countries are only part of this puzzle. Whether or not the Paris targets will be achieved will be largely determined by trends in developing countries. However, developing countries are largely dependent on the use of technologies currently available mainly in industrialized countries (with the exception of China and several other developing countries). They should also see good examples of how well-being and well-being can be achieved in a low-carbon economy.

North-South conversations in climate negotiations often revolve around remittances from the North to low-income countries in the South. The Paris Commitment, which has reached $ 100 billion annually since 2020, will also be used to adapt to an ever-changing climate. This amount is still modest compared to global fossil fuel subsidies, which are about five to six times higher. However, the practical problem is that the majority of governments and parliaments of the countries of the North believe that they have almost no opportunity to maneuver in their state budgets. The real wealth of these countries, as a rule, is in private hands.

This fact may lead to the development of a different strategy for the transition to a low-carbon economy. A convincing idea for such a strategy was developed in the 1990s by the late Anil Agarwal and his colleague Sunita Narain from India: the authors proposed to allow everyone on earth to have the same amount of resource consumption or greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere. Poor people can sell part of their benefits to the rich, alleviating their poverty, while maintaining a strong incentive for both rich and poor people to become more resource efficient and reduce their carbon footprint. Unfortunately, the idea of “one person, one equal benefit” did not receive the necessary support.

More than ten years later - and in order to facilitate climate negotiations at the COP (Copenhagen Climate Conference) 15 at the Copenhagen-German Consultative Council on Global Change (“WBGU”), it continued to develop this idea and presented a “budget approach”, schematically illustrated in Fig. 3.9. This approach meant giving all types of countries the same carbon budget per capita. Older industrialized countries will be forced to seek permits in less developed countries.

An interesting feature of this budget approach is that, for the first time in history, a developing country facing a decision to build a fossil fuel power station would not go for it automatically, but would deviate for a moment and then calculate the cost-benefit ratio for the two options. -construction or not construction. High prices for carbon permits will make the option without building temptingly lucrative. And if there are still many options for expanding renewable energy sources (section 3.4) or energy efficiency (section 3.8), the balance will quickly turn into a non-construction option. And this is for purely economic reasons.

Unfortunately, for climate talks the United States, Russia, Saudi Arabia and some others came to the climate summit in Copenhagen with a clear intention to block discussion of the budget approach. However, for the Club of Rome, it looks very attractive and deserves a revival.

Picture. 3.9 “budget approach”: rich countries (pink) have almost exhausted their CO2 emissions budgets. Dotted lines indicate the development of the budget prior to bidding. Developing countries (green) will have an excess of permits and may sell some of them, allowing rich countries to still emit CO2. Middle-income countries (yellow) can also buy permits after their budget can be reduced to zero in 2040 (Source: WBGU - German Advisory Council or Global Change (2009): addressing the climate dilemma: budget approach. Special report. Berlin: WBGU)

The budget approach is a tool for international transactions. At the domestic level, trade permits are much less attractive, as experience gained in the European Union (EU) emissions trading system shows. The price of emission allowances has been and remains too low to change anything. In practical terms, carbon taxes are much simpler and more efficient. The problem is that politically they are generally regarded as “toxic”, especially in the United States. One attractive way to move forward would be to follow Jim Hansen’s proposal, and more recently the proposed new (Republican) Climate Leadership Council (CLC) to introduce a carbon tax, but return the money to taxpayers on an equal and quarterly basis using dividend checks, direct deposits or contributions to their individual retirement accounts. If such measures are taken, then incentives to invest in alternative energy and fossil fuel-free industrial processes will receive an additional powerful impetus.

One of the problems with all taxes and carbon trading systems is that they either severely harm carbon issuers (it is extremely difficult politically), or are so tamed that they do not really help decarbonate the economy. One proposal, trying to combine advantages (politically acceptable and yet with a powerful effect), is discussed in sect. 3.12.3: a gradual increase in price in proportion to the documented increase in efficiency, so that annual expenditures on carbon or energy services remain on average stable.

Obviously, the practical steps taken so far by governments and private actors are far from sufficient to achieve the Paris goals. In response, an increasing number of commentators, including climate scientists, are advocating for massive mobilization, like war, to win in the fight against climate change. Hugh Rocoff, a professor of economics at Rutgers University, draws parallels between combating climate change and World War II. According to Rocoff, the scale of our financial difficulties in combating climate change is similar to those faced by our parents and grandparents during World War II. How they accomplished this - and what Rocoff suggests we do to win global warming - is to achieve huge government spending on infrastructure and technology.

The implication is that the time of "incrementalism" is over. Now we need to transform through technological innovation, substitution, and large-scale investment. Here governments have a key role to play.

As the Rome Club, we would prefer to avoid the term “military mobilization,” so let's use the term “post-war economy” instead. The United States, as well as the countries defeated in World War II, Japan and Germany, experienced a massive economic recovery after the war by building (or rebuilding) infrastructure and developing new technologies.

Politically working to change the framework conditions that promote radical changes, such as the transition to a “post-war economy” and / or adopting a budget approach, it is still necessary to use sectoral options, some of which are seizing, such as renewable energy, efficiency subsidies, reasonable mobility, agricultural reform, slowing deforestation, etc. It is necessary to change the political framework in order to stimulate the necessary technological changes. In addition, it is necessary to significantly increase support for research, innovation and demonstration projects from the public sector. In addition, government procurement — in many countries that account for a fifth of GDP — must be actively used to encourage low-carbon solutions. Crucial to supporting low-carbon infrastructure investments and more efficient use of materials. In addition, it will be necessary to oblige the financial industry to report the carbon risks of their lending.

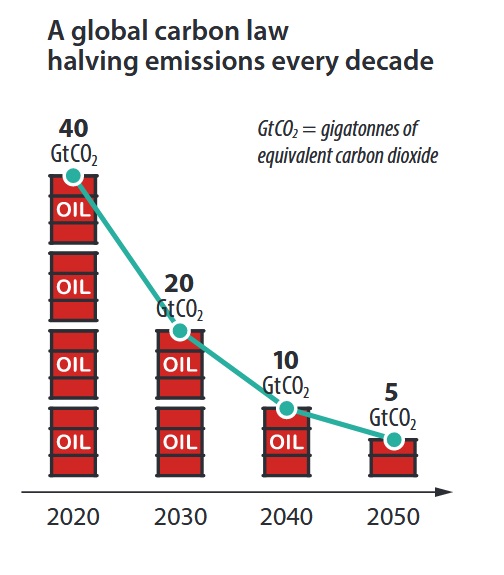

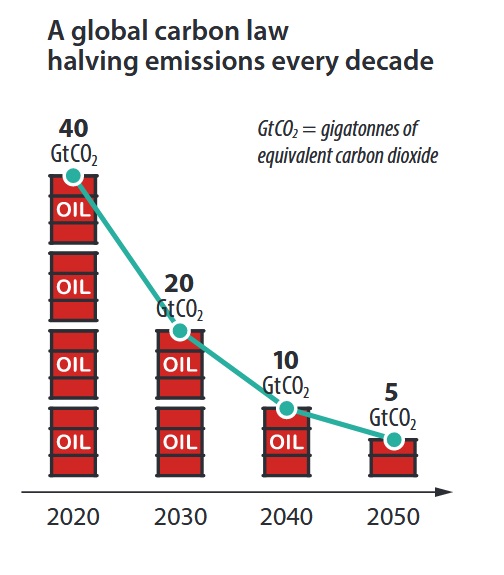

Picture. 3.10 Roadmap Mass Emission Reductions, believed to be done by Johan Rockström et al.

Innovation should pay much more attention to public goods, in this case low-carbon solutions. In our opinion, greed and the quickest return on investment dominate in innovation today. Governments should significantly increase funding for research and innovation in low-carbon solutions. But under the conditions outlined in section. 3.10 in the event of a steady and predictable increase in carbon emissions or more generally energy prices — preferably using a carbon tax — both governments and private investors will almost automatically change their priorities precisely in the desired direction.

Some of the world's most famous and respected climate experts — among them, Johan Rokstrom and John Shellhuber — challenged conventional wisdom in the article. The authors declare that, “although the objectives of the Paris Agreement are consistent with science and can in principle be technically and economically achieved, alarming discrepancies between scientifically based goals and national commitments persist.” They fear that long-term goals will be surpassed by short-term policies. Thus, they put forward a roadmap in the form of a “carbon law” - apparently inspired by Moore's law — which would imply a halving of carbon emissions every decade before 2050. Following this path, greenhouse gas emissions will be close to zero in 2050, which is a prerequisite for achieving a target of 2 ° with a high probability (Figure 3.10).

The roadmap affects all sectors and involves much more rapid action than has been discussed so far. Fossil fuel subsidies should be removed no later than 2020. Coal for energy output no later than 2030. You must introduce a carbon tax of at least $ 50 per ton. Internal combustion engines should no longer be sold after 2030. 2030 - -. . CO2 BECSS / (DACCS).

. . 2050 . , Krausmann . , « » (. . 3.8 3.9).

, , . . , . . . 100 : , , – . , «» , . , , — , . , .

12% 17% . , . , , « ». , - - , , .

. , , , , , . . . . . , .

. « » , , , «». . . . .

«» . - . . . , , , . - .

To be continued...

For the translation, thanks to Jonas Stankevichus. If you are interested, I invite you to join the “flashmob” to translate a 220-page report. Write in a personal or email magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

Foreword

Chapter 1.1.1 “Different types of crises and a feeling of helplessness”

Chapter 1.1.2: "Financing"

Chapter 1.1.3: “An Empty World Against Full Peace”

Chapter 3.1: “Regenerative Economy”

Chapter 3.3: The Blue Economy

Chapter 3.4: “Decentralized Energy”

Chapter 3.5: "Some Success Stories in Agriculture"

Chapter 3.6: “Regenerative Urbanism: Ecopolis”

Chapter 3.7: “Climate: good news, but big problems”

Chapter 3.8: “The economy of a closed cycle requires a different logic”

Chapter 3.9: “Fivefold Resource Performance”

Chapter 3.10: “Tax on Bits”

Chapter 3.11: “Financial Sector Reforms”

Chapter 3.12: “Reforms of the Economic System”

Chapter 3.13: “Philanthropy, Investment, Crowdsourse and Blockchain”

Chapter 3.14: "Not a single GDP ..."

Chapter 3.15: “Collective Leadership”

Chapter 3.16: “Global Government”

Chapter 3.17: “Actions at the National Level: China and Bhutan”

Chapter 3.18: “Literacy for the Future”

As already emphasized in Ch. 1, the world must undergo a quick and thorough transformation of its production and consumption systems in order to be able to stay within the “2 ° target”. Only the Paris Agreement and the measures taken by governments, far from reaching the goal. Instead of maintaining warming below 2 ° degrees, the world is on a path of 3 ° or more degrees. Heating the Earth by 2 ° (Celsius) is not only slightly worse than 1.0-1.3 ° (or so), we have already warmed it; it is much more dangerous. Three degrees is much more dangerous. Four means living on a frightening, chaotic planet, the like of which humans have never experienced.

So, the situation is critical. But let's start with the good news.

')

3.7.1 Good News

In paragraph 3.4, the exciting trend of a decentralized energy system was noted, starting with a quote from Amory Lovins: “Imagine fuel without fear. Without climate change ... ". The chapter says that over the past 10-20 years, renewable energy sources are becoming cheaper, and in the meantime, new coal and nuclear installations are losing ground. Figure 3.6 shows a seemingly fatal decline in the Dow Jones US Coal Index. Investors are switching to renewable energy sources.

The associated development provides additional grounds for hope: a widespread and global campaign for alienation, which was mainly driven by climate issues. By March 2017, 701 organizations, representing $ 5.46 trillion, had sold their shares of fossil fuel companies. It was the fastest growing movement to withdraw investment in history.

Accelerating the debate about "stuck assets" is another sign that change is in the air. As Alex Steffen writes in his blog (March 2017), “Fuel that cannot be burned does not cost much. In turn, companies whose main assets are in coal, oil and gas cost much less than their stock prices. The difference between the estimates of fossil fuel companies and their true value is so great that national banks, financial industries, associations and respected investors from all over the world warn that it represents a bubble potentially like the 2007 mortgage crisis. ”

For example, according to Barclays Bank estimates, limiting emissions to 2 ° C will reduce the future revenues of the oil, coal and gas industry by $ 33 trillion over the next 25 years. In January 2017, the Bank of England published a document in which it stated that the carbon bubble rupture was likely to be sharp and "likely to create risks for financial stability."

The price of something is that you can get someone to pay for it. For investors owning coal, oil and gas companies, supporting the view that these companies will be profitable in the future, is now a priority of several trillion dollars. This, by the way, seems to be one of the things that unites Trump and Putin. Both are genuinely interested in keeping the value of fossil assets at the highest possible level.

Another related issue is CO2 emissions from transport. But there is good news here, reports the Carbon Tracker Initiative and the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London. In essence, the presented scenarios suggest a sharp rise in solar electricity (PV, photovoltaic energy) and, in parallel, electric vehicles. If this happens, it is likely that the growth in world oil demand will stop already from 2020 and beyond and will lead to the depletion of fossil fuel reserves as the low carbon transition accelerates. The result may be more or less carbon-free mobility in a few decades. But this, of course, depends on the phase-out of coal as the main fuel for electricity generation.

In Section 3.9, evidence of the enormous potential for energy savings will be considered. It is possible to increase energy efficiency by a factor of five, which will drastically reduce the need for energy supply. However, to establish commercial profitability will require some major changes to the framework conditions, as discussed in section 3.10.

More other good news comes from another region. It was mainly a nine-year-old German boy, Felix Finkbeiner, who in 2007 began thinking about a big tree planting. After learning of the threats of global warming and hearing how Wangari Maathai and the green belt movement planted 30 million trees in Kenya, Felix argued that the children of the world could join in and plant many more trees. In the same year, the “plant for the planet” initiative was established, starting with the commitment to plant one million trees in each country of the world.

Movement grew faster than expected. They organized “academies” for children aged 8-14 years, giving them the opportunity to become ambassadors for climate justice. By 2016, 51,000 children from 193 countries received this title. The goal of the movement today is for every citizen of the world to plant 150 trees on average in order to reach 1000 billion trees by 2020. This would help absorb a significant portion of CO2 emissions.

Another impetus for action to combat climate change is the link with agriculture, as described in section 3.5. Soil restoration to high fertility is obviously useful for high yields of agricultural crops. But it also greatly increases the ability of soils to absorb CO2 (see also Section. 3.1.4). This means that the task of feeding the 7.5 billion people in the world should not conflict with the objectives of the climate policy, with the proviso that the number of livestock should be reduced rather than increased due to methane emissions from animal digestion.

3.7.2 Solving the problem of historical debt and the carbon budget approach

The Treaty of Paris is a call to action for all governments in the world. However, the necessary changes must begin in industrialized countries. They have built their standard of living on cheap oil and gas and are obliged to lead the developing world.

Of course, industrialized countries are only part of this puzzle. Whether or not the Paris targets will be achieved will be largely determined by trends in developing countries. However, developing countries are largely dependent on the use of technologies currently available mainly in industrialized countries (with the exception of China and several other developing countries). They should also see good examples of how well-being and well-being can be achieved in a low-carbon economy.

North-South conversations in climate negotiations often revolve around remittances from the North to low-income countries in the South. The Paris Commitment, which has reached $ 100 billion annually since 2020, will also be used to adapt to an ever-changing climate. This amount is still modest compared to global fossil fuel subsidies, which are about five to six times higher. However, the practical problem is that the majority of governments and parliaments of the countries of the North believe that they have almost no opportunity to maneuver in their state budgets. The real wealth of these countries, as a rule, is in private hands.

This fact may lead to the development of a different strategy for the transition to a low-carbon economy. A convincing idea for such a strategy was developed in the 1990s by the late Anil Agarwal and his colleague Sunita Narain from India: the authors proposed to allow everyone on earth to have the same amount of resource consumption or greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere. Poor people can sell part of their benefits to the rich, alleviating their poverty, while maintaining a strong incentive for both rich and poor people to become more resource efficient and reduce their carbon footprint. Unfortunately, the idea of “one person, one equal benefit” did not receive the necessary support.

More than ten years later - and in order to facilitate climate negotiations at the COP (Copenhagen Climate Conference) 15 at the Copenhagen-German Consultative Council on Global Change (“WBGU”), it continued to develop this idea and presented a “budget approach”, schematically illustrated in Fig. 3.9. This approach meant giving all types of countries the same carbon budget per capita. Older industrialized countries will be forced to seek permits in less developed countries.

An interesting feature of this budget approach is that, for the first time in history, a developing country facing a decision to build a fossil fuel power station would not go for it automatically, but would deviate for a moment and then calculate the cost-benefit ratio for the two options. -construction or not construction. High prices for carbon permits will make the option without building temptingly lucrative. And if there are still many options for expanding renewable energy sources (section 3.4) or energy efficiency (section 3.8), the balance will quickly turn into a non-construction option. And this is for purely economic reasons.

Unfortunately, for climate talks the United States, Russia, Saudi Arabia and some others came to the climate summit in Copenhagen with a clear intention to block discussion of the budget approach. However, for the Club of Rome, it looks very attractive and deserves a revival.

Picture. 3.9 “budget approach”: rich countries (pink) have almost exhausted their CO2 emissions budgets. Dotted lines indicate the development of the budget prior to bidding. Developing countries (green) will have an excess of permits and may sell some of them, allowing rich countries to still emit CO2. Middle-income countries (yellow) can also buy permits after their budget can be reduced to zero in 2040 (Source: WBGU - German Advisory Council or Global Change (2009): addressing the climate dilemma: budget approach. Special report. Berlin: WBGU)

3.7.3 Carbon Price

The budget approach is a tool for international transactions. At the domestic level, trade permits are much less attractive, as experience gained in the European Union (EU) emissions trading system shows. The price of emission allowances has been and remains too low to change anything. In practical terms, carbon taxes are much simpler and more efficient. The problem is that politically they are generally regarded as “toxic”, especially in the United States. One attractive way to move forward would be to follow Jim Hansen’s proposal, and more recently the proposed new (Republican) Climate Leadership Council (CLC) to introduce a carbon tax, but return the money to taxpayers on an equal and quarterly basis using dividend checks, direct deposits or contributions to their individual retirement accounts. If such measures are taken, then incentives to invest in alternative energy and fossil fuel-free industrial processes will receive an additional powerful impetus.

One of the problems with all taxes and carbon trading systems is that they either severely harm carbon issuers (it is extremely difficult politically), or are so tamed that they do not really help decarbonate the economy. One proposal, trying to combine advantages (politically acceptable and yet with a powerful effect), is discussed in sect. 3.12.3: a gradual increase in price in proportion to the documented increase in efficiency, so that annual expenditures on carbon or energy services remain on average stable.

3.7.4 Combating global warming with a “post-war economy”

Obviously, the practical steps taken so far by governments and private actors are far from sufficient to achieve the Paris goals. In response, an increasing number of commentators, including climate scientists, are advocating for massive mobilization, like war, to win in the fight against climate change. Hugh Rocoff, a professor of economics at Rutgers University, draws parallels between combating climate change and World War II. According to Rocoff, the scale of our financial difficulties in combating climate change is similar to those faced by our parents and grandparents during World War II. How they accomplished this - and what Rocoff suggests we do to win global warming - is to achieve huge government spending on infrastructure and technology.

The implication is that the time of "incrementalism" is over. Now we need to transform through technological innovation, substitution, and large-scale investment. Here governments have a key role to play.

As the Rome Club, we would prefer to avoid the term “military mobilization,” so let's use the term “post-war economy” instead. The United States, as well as the countries defeated in World War II, Japan and Germany, experienced a massive economic recovery after the war by building (or rebuilding) infrastructure and developing new technologies.

Politically working to change the framework conditions that promote radical changes, such as the transition to a “post-war economy” and / or adopting a budget approach, it is still necessary to use sectoral options, some of which are seizing, such as renewable energy, efficiency subsidies, reasonable mobility, agricultural reform, slowing deforestation, etc. It is necessary to change the political framework in order to stimulate the necessary technological changes. In addition, it is necessary to significantly increase support for research, innovation and demonstration projects from the public sector. In addition, government procurement — in many countries that account for a fifth of GDP — must be actively used to encourage low-carbon solutions. Crucial to supporting low-carbon infrastructure investments and more efficient use of materials. In addition, it will be necessary to oblige the financial industry to report the carbon risks of their lending.

Picture. 3.10 Roadmap Mass Emission Reductions, believed to be done by Johan Rockström et al.

Innovation should pay much more attention to public goods, in this case low-carbon solutions. In our opinion, greed and the quickest return on investment dominate in innovation today. Governments should significantly increase funding for research and innovation in low-carbon solutions. But under the conditions outlined in section. 3.10 in the event of a steady and predictable increase in carbon emissions or more generally energy prices — preferably using a carbon tax — both governments and private investors will almost automatically change their priorities precisely in the desired direction.

Some of the world's most famous and respected climate experts — among them, Johan Rokstrom and John Shellhuber — challenged conventional wisdom in the article. The authors declare that, “although the objectives of the Paris Agreement are consistent with science and can in principle be technically and economically achieved, alarming discrepancies between scientifically based goals and national commitments persist.” They fear that long-term goals will be surpassed by short-term policies. Thus, they put forward a roadmap in the form of a “carbon law” - apparently inspired by Moore's law — which would imply a halving of carbon emissions every decade before 2050. Following this path, greenhouse gas emissions will be close to zero in 2050, which is a prerequisite for achieving a target of 2 ° with a high probability (Figure 3.10).

The roadmap affects all sectors and involves much more rapid action than has been discussed so far. Fossil fuel subsidies should be removed no later than 2020. Coal for energy output no later than 2030. You must introduce a carbon tax of at least $ 50 per ton. Internal combustion engines should no longer be sold after 2030. 2030 - -. . CO2 BECSS / (DACCS).

. . 2050 . , Krausmann . , « » (. . 3.8 3.9).

, , . . , . . . 100 : , , – . , «» , . , , — , . , .

12% 17% . , . , , « ». , - - , , .

. , , , , , . . . . . , .

. « » , , , «». . . . .

«» . - . . . , , , . - .

To be continued...

For the translation, thanks to Jonas Stankevichus. If you are interested, I invite you to join the “flashmob” to translate a 220-page report. Write in a personal or email magisterludi2016@yandex.ru

More translations of the report of the Club of Rome 2018

Foreword

Chapter 1.1.1 “Different types of crises and a feeling of helplessness”

Chapter 1.1.2: "Financing"

Chapter 1.1.3: “An Empty World Against Full Peace”

Chapter 3.1: “Regenerative Economy”

Chapter 3.3: The Blue Economy

Chapter 3.4: “Decentralized Energy”

Chapter 3.5: "Some Success Stories in Agriculture"

Chapter 3.6: “Regenerative Urbanism: Ecopolis”

Chapter 3.7: “Climate: good news, but big problems”

Chapter 3.8: “The economy of a closed cycle requires a different logic”

Chapter 3.9: “Fivefold Resource Performance”

Chapter 3.10: “Tax on Bits”

Chapter 3.11: “Financial Sector Reforms”

Chapter 3.12: “Reforms of the Economic System”

Chapter 3.13: “Philanthropy, Investment, Crowdsourse and Blockchain”

Chapter 3.14: "Not a single GDP ..."

Chapter 3.15: “Collective Leadership”

Chapter 3.16: “Global Government”

Chapter 3.17: “Actions at the National Level: China and Bhutan”

Chapter 3.18: “Literacy for the Future”

"Analytics"

- "Come on!" - the anniversary report of the Club of Rome

- The anniversary report of the Club of Rome - embalming capitalism

- Club of Rome, jubilee report. Verdict: “The Old World is doomed. New World is inevitable! ”

- Hour: Report of the Club of Rome. Orgies of self-criticism

About #philtech

#philtech (technology + philanthropy) is an open, publicly described technology that aligns the standard of living of as many people as possible by creating transparent platforms for interaction and access to data and knowledge. And satisfying the principles of filteha:

1. Opened and replicable, not competitive proprietary.

2. Built on the principles of self-organization and horizontal interaction.

3. Sustainable and prospective-oriented, and not pursuing local benefits.

4. Built on [open] data, not traditions and beliefs.

5. Non-violent and non-manipulative.

6. Inclusive, and not working for one group of people at the expense of others.

Philtech's social technology startups accelerator is a program of intensive development of early-stage projects aimed at leveling access to information, resources and opportunities. The second stream: March – June 2018.

Chat in Telegram

A community of people developing filtech projects or simply interested in the topic of technologies for the social sector.

#philtech news

Telegram channel with news about projects in the #philtech ideology and links to useful materials.

Subscribe to the weekly newsletter

#philtech (technology + philanthropy) is an open, publicly described technology that aligns the standard of living of as many people as possible by creating transparent platforms for interaction and access to data and knowledge. And satisfying the principles of filteha:

1. Opened and replicable, not competitive proprietary.

2. Built on the principles of self-organization and horizontal interaction.

3. Sustainable and prospective-oriented, and not pursuing local benefits.

4. Built on [open] data, not traditions and beliefs.

5. Non-violent and non-manipulative.

6. Inclusive, and not working for one group of people at the expense of others.

Philtech's social technology startups accelerator is a program of intensive development of early-stage projects aimed at leveling access to information, resources and opportunities. The second stream: March – June 2018.

Chat in Telegram

A community of people developing filtech projects or simply interested in the topic of technologies for the social sector.

#philtech news

Telegram channel with news about projects in the #philtech ideology and links to useful materials.

Subscribe to the weekly newsletter

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/421395/

All Articles