The book about the "Paragraph" on Habré. Chapter One: The Watchman

What is it about? " Paragraph " is the first Russian startup to conquer the world. And he could hardly have been born at all if Stepan Pachikov and Garry Kasparov had not organized the first children's computer club in Moscow.

It was the knowledge, connections and reputation acquired at the post of its director that allowed Stepan to Perestroika to launch his own software sales cooperative. So the whole mess with the "Paragraph" and began.

')

Kasparov and Pachikov in the computer club for children - a photo of 1987 ( published on the Republic.ru website )

Kasparov and Pachikov in the computer club for children - a photo of 1987 ( published on the Republic.ru website )Well, this chapter is just about a very nontrivial chain of events, which led Pachikov, in general, an ordinary employee of the Academy of Sciences, to get acquainted with the world champion in chess and the opening of a unique club for those times.

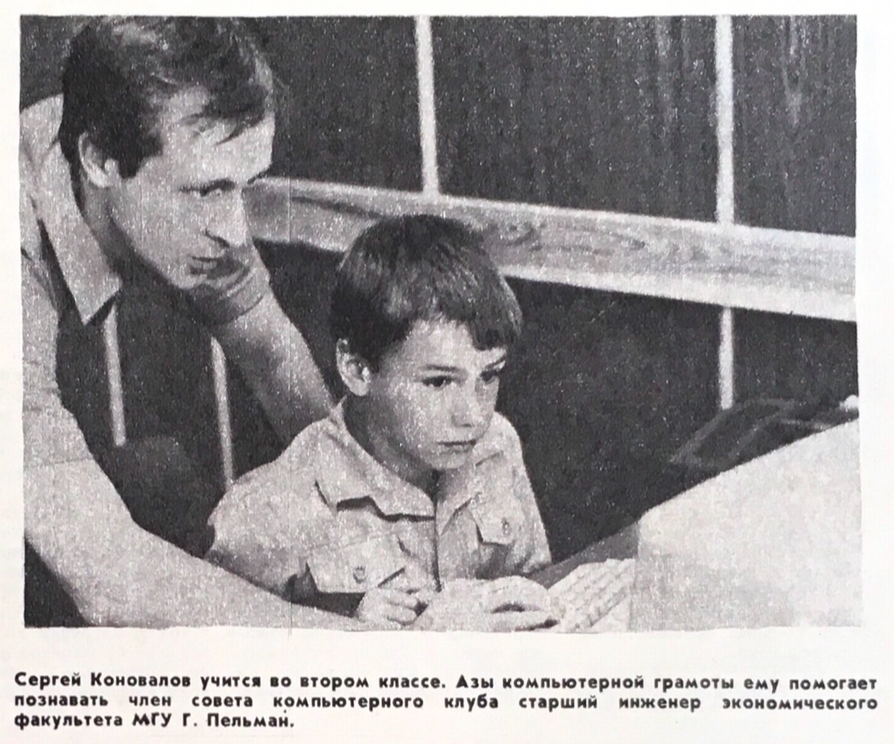

Club photo from an article in the magazine "Radio". 1987

Club photo from an article in the magazine "Radio". 1987An instructive story about how chance and faith in the best can radically change life and in fact predetermine destiny. Well, the reason to ponostalgate about computers Z80 and floppy disks for those who found those times ...

I must say that technically is the second chapter. The first, introductory, tells the personal story of the protagonist, and to the world of technology is not directly related. Therefore, we skip it. This space does not hurt reading.

It is enough to know about the missed chapter that being a student, Pachikov wrote on the wall the slogan “Czech Republic - Czechs” after the Soviet troops entered Czechoslovakia . For which he was first kicked out of the University of Novosibirsk, and then almost knocked out of Tbilisi. And only the occasional intervention of an influential friend allowed him to get a diploma and begin a scientific career.

Finally, let me remind you that you can always subscribe to the project’s newsletter and immediately receive a letter in all the ready-made chapters in the form of a pdf or epub - so far there are nine of them, counting the one that I sent to subscribers just today. Well, do not forget about the podcast with fragments of the book .

Go!

Watchman

Pachikov became the founder of the computer club, from which the Paragraph would grow up later, only because he once decided to go to work at night as a janitor in a hostel.

This radical career step determined his fate much more than the service in the USSR Academy of Sciences, which for some time remained for him the main place of work.

Watchmen were a unique product of the Soviet system. They carried their service at the entrance to any more or less significant institution. What for? This remained a mystery.

Not to ensure security - the janitors had neither training nor adequate equipment, and in most cases their objects were of no interest to potential intruders. They also proved powerless to prevent theft at their offices.

Vakhtera often kept records of incoming and outgoing, recording the passport data of each guest in hand-lined notebooks with corners twisted from frequent use. But this work was usually carried out carelessly and very rarely had practical meaning.

And certainly the Soviet janitors did not render any services to the visitors of the institutions - the concept of “service” was unfamiliar to the person born in the USSR - they did not provide any service anywhere and never waited. Often on the booths of the Soviet watchmen there was a laconic inscription: “We do not give any certificates”.

The watchmen, however, fulfilled an important function for Soviet society — they created an illusory, but acceptable for all, illusion of order and control.

In other words, the mission of Pachikov in the dormitory duty station position was to sit in the chair assigned to him during the hours assigned to him and accompany the people passing by with a stern look.

Most of the time he neglected his duties and read books. "Working" the night after three, Pachikov received sixty rubles a month - against one hundred and eighty, which he was paid at the Academy.

Looking at Pachikov, many inhabitants of the hostel certainly did not believe that he was a scientist - why would an employee of the main scientific institution of the country work as a simple watchman?

They did not think that he was sitting on a worn chair and was asking himself the question that after thirty overcomes many people: how did this happen? Yet it started so well - and it was so banal.

By that time, ten years had passed since he happily escaped major troubles in Tbilisi and went to Moscow to conquer the capital of the Soviet empire.

Stepan himself did not notice how from a promising young man he turned into a scientist with an ordinary career - and a man who had to look for a side job in order to feed his family.

Behind his back remained both graduate school, and marriage, and the birth of the first child, and the unfinished dissertation on the theory of fuzzy sets, and work at the Moscow State Farm, for which he went, in general, only for the sake of registration in the Moscow region.

Only Moscow opened up career opportunities and provided an acceptable level of comfort, as well as access to culture. But in the Soviet Union there was neither private property nor the housing market as such - it was impossible to buy an apartment with a mortgage, just as it was impossible to officially rent it in some apartment building.

In order to live in the capital, it was necessary either to be born and grow up there, or to go to study at one of the local institutions, which would provide a hostel, and then find a job in an organization that could provide an official Moscow residence permit.

The service on the state farm did not promise any scientific discoveries to Pachikov - the tasks there were mostly administrative. He was assigned to supervise the project to establish electronic document management in the accounting department.

However, the farm closed the issue with registration, providing a new employee housing in the Moscow suburbs.

In addition, Stepan was given a salary of two hundred and seventy rubles, which at first seemed monstrous to him, and was given the opportunity to officially buy his products at the state farm - tomatoes and champignons.

The monthly norm of products put to each employee was very modest. To buy an extra box of mushrooms, the signature of one of the deputy directors was required. But even such an insignificant privilege mattered: products in the USSR were worth more than money.

In the country, the most banal food items remained in short supply - because of the iron curtain and the desire to produce everything on their own, multiplied by unfavorable climatic conditions and an inefficient model of Soviet management.

Even with cash, good products could not be bought in stores - it was necessary to “get”. Change from those who have access to them.

Often this meant: I learned to systematically steal from the institution in which I served or worked — not everyone had the opportunity, like Pachikov, to acquire them legally.

On the gray market for grocery barter, tomatoes and mushrooms were considered a liquid commodity. They could exchange meat, fish, vegetables, sausage ... For many, access to the deficit was a weighty argument in favor of holding on to work at the state farm.

Pachikov managed to resume his scientific career only after five years. Stepan was appointed as a senior researcher in the advisory group under the president of the Academy of Sciences, which was engaged in economic modeling in the energy sector. There, he could at least apply his knowledge of cybernetics. The transition to the Academy hit the family budget - they paid one and a half times less there.

For some time, the scientist’s family was saved by kimonos for karate in the evenings by order of a familiar trainer, in whose group Stepan was engaged in this fashionable sport.

The government did not encourage such "left" wages - although they were not formally prohibited. Why does a Soviet person need additional income if society provides him with everything he needs - the fairest of all?

Despite the official doctrine, like Pachikov, many people were looking for a way to improve their situation without advertising their commercial activities. According to the estimates of researchers, even in the "stagnant" seventies, ten to twelve percent of the income of Soviet citizens were informal private earnings. For the intelligentsia, tutoring was the most familiar thing.

In addition to cutting and sewing kimono, Stepan was engaged in even more dubious activities from the point of view of the Soviet government - through a familiar translator from the publishing house Progress, he bought literature forbidden in the USSR in the West and distributed it among friends and acquaintances.

Progress produced Soviet propaganda in fifty languages — it was intended for export. Therefore, out of almost a thousand employees of the institution, many were foreigners-translators.

One of them decided to have a hand not only in exports, but also in the import of cultural property.

Christopher English began his underground activities by bringing films with the records of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, and then he switched to something more serious - books forbidden in the USSR by Solzhenitsyn, Shalamov, Brodsky and other hostile or simply unreliable authors ...

They were published in the West - including in Russian. The translator brought them into the country through familiar ambassadorial workers and gave them to his good friend - friends brought him to him, introducing him as a person who can be trusted with such a delicate matter.

This man was Stepan Pachikov. Having received the forbidden books from the translator, he distributed them among his acquaintances - and he was engaged in such activities with enthusiasm, who could not find a way out at official work, either at the state farm or at the Academy.

For several years, hundreds of forbidden books passed through the hands of a scientist. For the literary monuments of human cruelty and meanness most hated by the Soviet regime — the books of Shalamov or Solzhenitsyn — he could easily get several years of camps.

At the same time, Pachikov was also a participant in the completely official society of book lovers, which existed in the USSR at almost every enterprise and were supposed to contribute to the dissemination of ideologically verified Soviet prose.

Among the complete junk there came across more or less decent things. For their sake, Stepan gained everything he was given. His activity did not go unnoticed, and once Pachikov was awarded a diploma "For the active dissemination of social and political literature."

He proudly hung it at home on the wall - right above the place where he kept the stacks of forbidden books.

It was Chris who helped Pachikov get a job as a janitor - let him know that a promising vacancy had opened in the dormitory of his publishing house. Stepan seized the opportunity without hesitation - and happily exchanged sewing kimonos to sit on his pants.

Working as a janitor, you could get money without doing anything. In addition, the hostel, strictly speaking, was not a hostel, but an apartment building, only unusual - mostly foreign employees of Progress lived in it.

And in the Soviet Union, where it was extremely difficult for an overseas citizen to get there, acquaintances with foreigners promised new, albeit uncertain and dangerous, opportunities.

Not believing in the legend of an employee of the Academy of Sciences, some residents of the house believed that Pachikov was actually a KGB officer who was assigned to look after guests.

But should the omnipresent State Security Committee keep translators under the hood - like all other people with passports of foreign countries, potential saboteurs and spies?

Stepan wore his father's officer shirts. Partly out of respect for his memory - his father died shortly after Tbilisi history. Partly because in the Soviet Union it was not so easy to find a good men's shirt.

These officers' shirts only reinforced the suspicions of the inhabitants of the house that their new watchman was not at all the one for whom he pretended to be.

However, the actor played his part so well that one day one of the tenants, Finn Aki Paananen, decided to go all in and asked: Will Stepan help him figure out how to get sense from this button box, called the personal computer?

A newly acquired “box” was the Commodore 64 . It was one of the first mass personal computers in history.

His debut version - Commodore PET - appeared in 1977, a few months before Apple II - the very invention that opened the new era in the digital industry, turning the company of two Steves - Jobs and Wozniak - into one of the most successful IT companies of its time. .

Before, only scientists and corporate employees enjoyed access to computers - computers of the seventies were too cumbersome and expensive for private users. They cost several million dollars and were rented out for tens of thousands a day.

Commodore, Apple, and then the British Sinclair Research brought to the market a machine of a completely different category - relatively compact and inexpensive, they were intended for home use.

For several years, people have appreciated the opportunities that personal computers gave. They allowed to type and edit texts, work with tables and even play, controlling the drawn spacecraft (which, however, looked rather conditional, since it was indicated by lines alone - stars shone through its body).

Commodore 64, which was purchased by a translator, was the third most popular model in the line of an American company. Sales of this car were already estimated in millions of pieces.

Despite its mass character, the computer did not look too easy to master. At the start, the inscription “Ready” flashed on the blue screen and on the next line - a white square, in place of which a letter appeared if the user pressed a key.

The first thing that usually occurred to a normal person was to enter the word “Hello” and press “enter”. In response, the car gave out a mysterious inscription: "? Syntax Error".

Pachikov difficulties not frightened. He was able to program on BESM-6 - the Soviet semiconductor computing machine, which was released from the late sixties. And in their laboratory at the Academy of Sciences, he worked with a Wang mini-computer.

Stepan asked to leave him with a “box” and instructions for him - and in a couple of nights he figured out the Commodore 64 so well that he managed not only to teach the owner of the device how to handle it, but also created a keyboard driver that allowed typing in Russian .

For a person working with two languages, this upgrade turned a computer into a full-fledged work tool. When the startled translator asked how to thank him, Pachikov asked him to subscribe to computer magazines.

Power in the USSR jealously watched where citizens get information about the world. Therefore, an ordinary Soviet person had no opportunity to subscribe to the Western press.

Scientists who could not be completely cut off from the rest of the world were allowed to read foreign periodicals in a specialized library. However, this was not very convenient. In addition, magazines appeared there with a delay of several months, sometimes in the form of photocopies from which advertisements and articles were withdrawn that were not necessary or harmful for a Soviet scientist.

Aki wrote all the major computer magazines in his name - and gave them to Stepan. Studying the press, he not only began to improve his English, but also became a dock for personal computers.

Colorful advertising in these magazines carried no less useful information than the publications themselves. Studying it, one could understand the scale of the changes taking place in the world of technology.

Soon, of course, he was scared to get his own computer. But how to do that?

The Iron Curtain separated the USSR from the rest of the world — and complicated relations with Western countries, which, since the end of World War II, tried to prevent the export of technology to the USSR, primarily military.

In 1980, in response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the administration of American President Jimmy Carter imposed a complete ban on the supply of any technology to the Union, including computers.

But here Pachikov was helped by another Progress employee and the inhabitant of the house he guarded - Dutchman Rob Wunderink.

Rob translated into Dutch Soviet periodicals and considered this occupation more destructive to the brain than alcohol abuse.

But such was the price for living in the USSR — and for the opportunity to write articles about Soviet reality for Dutch magazines. Young Wunderinka was little interested in the official news agenda - he wanted to talk about what this amazing country really lived. Pachikov became his guide.

Stepan showed the Dutchman how to buy sausage and tea, entering the store from the back door, because neither sausage nor tea was on the shelves. Stepan drove Ron through Soviet eateries and taught how to drink beer and eat a consignment, the existence of which the Dutchman had never suspected.

Rob's reports did not inspire delight in the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From the point of view of officials, he had no right to write anything at all about his life in Moscow, since no one gave him journalistic accreditation.

Helping the Dutchman, his guide went to some non-zero risk. And when Vunderink decided to buy a computer in Holland, Stepan gained impudence and asked for a counter service - bring the car to him too.

They purchased the most advanced computers of the time - Amstrada on the Z80 processor. Pachikov was particularly proud of the block he chose, which was responsible for loading data - a floppy disk drive.

Floppy disks allowed to load programs into the RAM of the machine in seconds. Less sophisticated computers at the time used to download audio tape - the process of launching the program took a few minutes and did not always end safely.

Thus, thanks to the work of the janitor in the house for foreigners and the acquaintances obtained there, Stepan got something more scarce in the Soviet Union than sausage and champignons: his own computer.

Pachikov was stunned by the opportunities that personal computers provided. For a resident of the Soviet Union, freedom in handling information carried a special meaning.

First, to make a copy of a book prohibited by censorship, it was necessary to manually, page by page, to reprint it on a typewriter. Now you could just give the computer the command "copy" - and that's it.

Stepan believed that home computers would put an end to total censorship. And after the fall of censorship, the totalitarian system, which he still hated with all his heart, will inevitably fall.

Knowledge about the development of the computer industry - now not only theoretical, but also practical - overwhelmed Pachikov. I wanted to share them.

With the help of Rob, Stepan acquired an Epson 80 needle printer and began to publish a digest in which he reviewed the latest computer innovations and retold key news from foreign magazines. He himself composed and typed texts, himself typed, he himself typed.

Stepan handed out a digest of acquaintances - often they were the very same people that previously received prohibited literature from his hands. Demand for its computer periodical grew by the day.

Along with demand, the glory of the “publisher” also grew - he soon became known in Moscow scientific circles as a computer specialist and enthusiast of the digital revolution.

Building economic forecasts, Pachikov remained only one of the ordinary scientists in the service of the Academy of Sciences. Inspired by the "personalkami", he turned into a unique expert - in the new field, which gained momentum every year.

Sometimes it seems that many people who have succeeded in life to succeed and soar exponentially have simply found themselves in the right place at the right time. As the Chinese say: a big wave raises all the boats.

Getting to the right place at the right time, however, is not so easy. To be on the wave, it takes both the boat and the oars, and, most importantly, the belief that there, beyond the horizon, a new earth - and a new, better life.

After all, this belief forces a person to leave familiar shores.

It was necessary to have a fair imagination in order to sit in a typical Soviet apartment and look at the blue screen of the low-power Amstrad, to believe in the future full triumph of units and zeros over the world of typewriters and folders.

Pachikov from a lack of imagination never suffered.

In Soviet Moscow in the mid-eighties it was difficult to find a scientist who was more fervently ready to convince everyone that computers would soon turn people's lives and become as common as a home TV or telephone.

Sooner or later, it all had to turn into something more. So it turned out.

The enthusiastic scientist was invited to speak at the computer seminar of the physicist Yevgeny Velikhov . This acquaintance opened up completely new opportunities for Pachikov - by that time Velikhov had been the vice-president of the Academy of Sciences for more than ten years.

Stepan spoke with dignity and became a regular participant in the seminar. In addition, he was included in the working group, which, under the leadership of the vice-president of the Academy, was engaged in developing the concept of computerization of Soviet schools.

Things did not get any further from the group, but Stepan gave a good account of himself. And when Velikhov had the idea of organizing the first computer club in the USSR, he immediately thought of Pachikov. Academician invited him to take the initiative and discuss the idea of the club with chess player Garry Kasparov.

The young Soviet grandmaster, Kasparov, was then only twenty-three years old - he had just won not one, not two, but fifty Atari computers and did not fully understand what to do with them.

To be continued...

If you like it, subscribe to the newsletter to get all the finished chapters in one file.

I would be happy reviews and constructive criticism.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/421283/

All Articles