Expedition to the mysterious fairy circles in the Namib Desert

Where the movie “Mad Max: Fury Road” was filmed, the scientist is trying to understand a natural phenomenon that has not been satisfactorily explained for several decades.

One evening, this spring, German naturalist Norbert Jürgens fought off an expedition in the Namib desert. He moved away from the camp, which was not far from the Leopard stone, a huge pile of slabs of slate, lying on top of each other, like tiles, and went along a huge plain bounded by red hills. There was still 20 minutes left before sunset, and he was going to use them.

The following events may seem to be a production from a documentary about nature, but trust me - that was how it was.

')

Jurgens, who went walking alone, fell to his knees. He plunged his tanned hands into the sand to the elbows. And while he was rummaging in the sand, an insight came upon him - as he told me later.

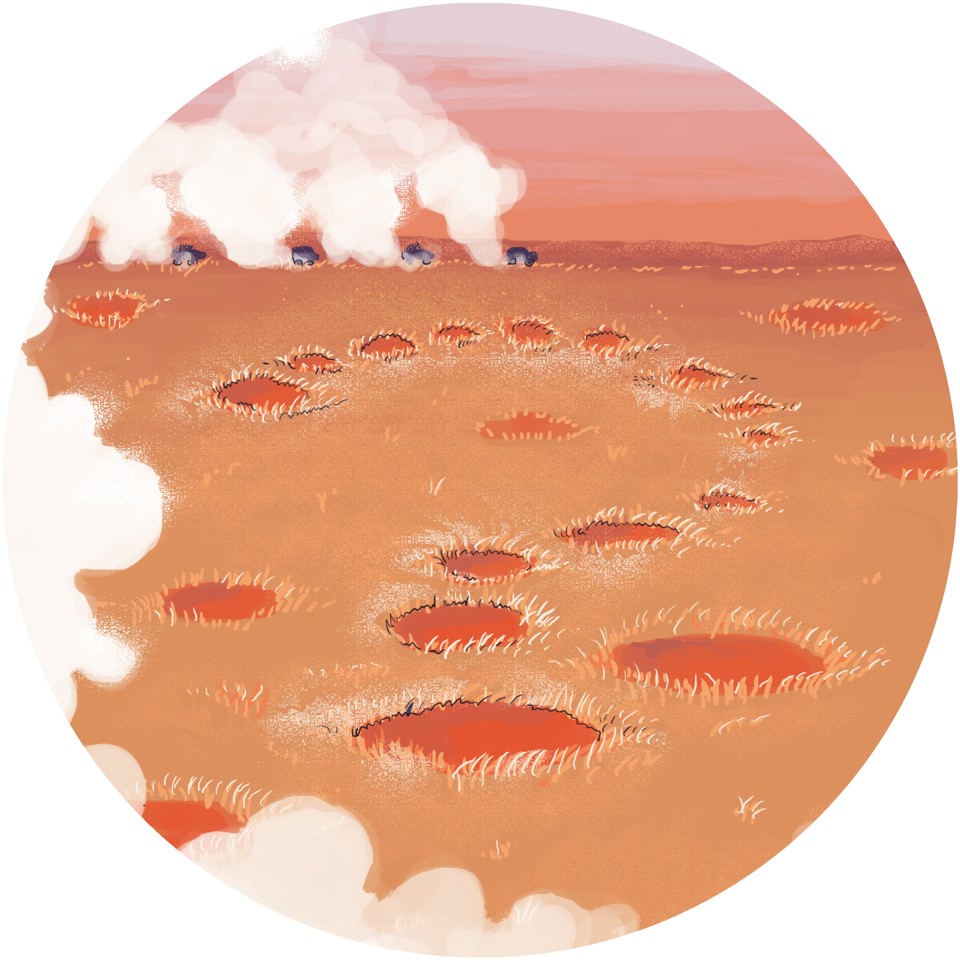

At that moment I was watching what was happening from the top of the Leopard stone, which allowed us to see from the height both Yurgens and the excavations of his expedition. Across the plain, as if stamped in its dry, barbed grass, there were circles of empty earth, each one the size of a small pool. Jurgens, a professor from the University of Hamburg, was digging - at the same time thinking - in one of these areas.

These spots are mysterious fairy circles [ not to be confused with witch circles formed by mushrooms / approx. trans. ] in Namibia, and they have attracted visitors to the desert for decades, including our caravan. In recent years, Yurgens and other researchers have fiercely argued about how and why these circles appear, disagreeing about the data and theories both personally and on the pages of the most respected journals in the world.

But this is not just academic controversy about tourist wonders. Fairy circles are a check of the emerging scientific field of analysis of biological patterns, and they can contain an encrypted message about the future of desert ecosystems - as well as people trying to survive in them.

* * *

Fairy circles are found in the drained, sandy soils of the Atlantic side of southern Africa, along a narrow strip from north to south, stretching more than fifteen hundred kilometers from the Richtersfeld mountains to the south of Angola.

The smallest circles of fairies reach one and a half meters in diameter, and the farther you go to the north, the more they become. The largest circles located in Angola can grow up to 40 meters. Such a circle can last at least 75 years - and, possibly, several centuries. Among the multitude of their strange properties is the frightening magnetism of a small force: if you drag a magnet along the inside of a circle, it will collect much more soil than outside.

Since the 1970s, scientists have made the most incredible assumptions about the origin of the fairy circles. Bare spots can be caused by chemicals secreted by Euphorbia damarana - Dummar milk grass, a toxic growth. Or it may be the places where the voracious termites of Hodotermes mossambicus eat. Perhaps these are the fossil nests of termites; it is possible that the vegetation inside them died due to natural radiation, or the leakage of hydrocarbons. And, of course, there is always a UFO version.

The fairies first met their circles in 1980 when, as a graduate student, he traveled to South Africa to the Richtersfeld nature reserve to study plants that had adapted to life in the desert, “living stones” of Lithops . But this mystery captured him only a couple of decades later.

In 2000, he began working as a scientific coordinator for BIOTA, an expanding network of research stations measuring environmental measurements in southern Africa. This project led to the emergence of SASSCAL , the South African Climate Change Service Center and Adaptive Land Management, a huge EU-funded project supporting the work of a scientist along with the University of Hamburg.

Yurgens began to observe fairy circles from year to year, looking for information among the data streams from observation stations studying the environment. His curiosity intensified. In the mid-2000s, he took samples from the locations of fairy circles in order to form his own idea of this problem. Yurgens dug round and round, measuring soil moisture and other quantities, and made a table where he listed all the plants and animals he had encountered nearby. “When I gathered them all together,” he said, “only one column turned out to be completely full.”

Jurgens spent the last five years categorically claiming that the real culprit for the appearance of circles is not the termites of the Hodotermes species, but of a completely different kind - tiny, barely distinguishable inhabitants of the Psammotermes allocerus sands. This conclusion made it a center of debate, which continues to this day.

This year I joined him on one of his regular expeditions to the wilderness. He is still collecting data and testing his theory, and as I watched him that evening, digging in the sand until the sun hid behind the hills, he might have lifted the veil a little more of this mystery.

* * *

You need to understand that termites are a very serious matter. If we collected all sentient beings from the global tropics and placed them on scales, then the termites would pull on 10% of the total weight. Only in Africa alone, there are more than 1,000 species of termites, including the genus Macrotermes , which build a cathedral-type termitary mound , sometimes exceeding the elephant's height.

Their visible biological trail is of interest not only to scientists. Various African aboriginal groups use termites for their own purposes, according to a recent ethnobiological study . Termites are rich in protein and are often eaten; in some parts of Rwanda, living termites are used for stapling wounds; in Benin, mold from thermite nests is sometimes mixed with honey to make a memory tonic; on Cote d'Ivoire, the Agni people bury their loved ones in abandoned mounds.

But the Psammotermes allocerus species was little described and studied, and when I first met Jurgens, I did not know at all what to expect.

On our expedition there were 13 people. In addition to Jurgens and I, it consisted of three Jurgens laboratory workers, an assistant from Namibia named Vilho Mutouleni nicknamed Snakes, and a crowd of students graduating from Hamburg University.

We gathered at the end of February in the capital of Namibia Windhoek , a city that had not yet fully recovered from the heritage of the colonial government of Germany, and later from apartheid in South Africa.

Having bought provisions, we in a caravan of off-road vehicles hit the road, raising clouds of dust. The farther we moved west from central Namibia towards the Atlantic, the drier the land became.

When I was not busy shifting the manual gearbox of my pickup, I noticed some things. Transfers through the dried up rivers. Twisted nests of birds. Huge red termitaries Macrotermes, sticking out like thumbs hitch.

That night we camped next to the sandy, dry riverbed of the Aba-Huab River. The next day, Yurgens led our caravan along the riverbed, past the irritable desert elephants, into the attractive area for its breadth, the distant hills of which asked them to climb them.

You saw the Namib Desert [ interestingly, in the language of the local people, “Namib” means “a place where there is nothing” - that is, in essence, a desert / approx. trans. ] if you watched the movie “Mad Max: Road of Fury”, where she played the role of an apocalyptic future. But Namib looked exactly the same as today, the last 55 million years, and maybe more, and all these countless years of its plants and animals evolved, faced with impossible conditions.

We drove forward. And suddenly, they appeared. Jurgens, who was at the head of the caravan, stopped, and everyone else followed suit. He went to the foot of the hill, I ran to catch up with him, and a gaggle of students followed me. “Your first fairy circle,” Yurgens told me when we all gathered. We ourselves became a circle near the tall grass growing on the edge of the bare spot, and Yurgens watched the site as an astronomer, taking apart a spiral galaxy. He pointed to the most obvious sign of the presence of his sandy termites: a wad of grass wrapped in sand tubes. Termites build tubes around the stems they eat, as he explained, crumbling the part of the tube between the fingers.

Then he gave us a tour of his version of the anatomy of the circle of fairies, a theory he first published in the journal Science in 2013. In the center is a bare plot. He is surrounded by what he calls the perennial belt, or the narrow ring of the highest and healthiest grass nearby. Then comes the halo, a wider ring of still healthy grass. Between the circles are rings of a more rarefied grass, which he calls the matrix. Yurgens looked approvingly at the sketch that I did in my journal.

In his work, it is argued that the modest termites of the species Psammotermes arrange circles of fairies to influence their surroundings, just like beavers build dams. From his point of view, each circle works as a reservoir - a hydrological accumulation account.

The idea is as follows. When it finally rains on the sands of Namib, the sun and the roots of the plants immediately suck the water out of the ground. But inside the bare spots, sandy termites gnawed all the roots of the plants, blocking their growth. The lack of plants allows rainwater to penetrate deeper into the soil, to the deeper layers, where it remains in the pores between the granules. According to the measurements of Jurgens, the soil at 60 cm below the surface of the circle of fairies is more humid than the soil outside, at about 5% by volume of liquid. He suggests that in these places, termites can satisfy thirst all year round, using special parts of the mouth to suck water from the sand.

Such a strategy can help termites store food. Allowing the grass in the perennial belt and halo to feed on their water supplies, he believes that termites guarantee the survival of part of the plant even during droughts. As for the mysterious magnetism of the plots, it may appear due to the fact that the wind carries away small particles of sand, leaving heavier granules rich in iron content.

Collecting evidence of his theory, Yurgens wrote down how dozens of other animals use the presence of water and plants. Ants and gerbils live beneath the surface of bare patches along with termites. Antelopes often rest there. Orycats dig sand and eat termites.

Leaving the first circles, we drove back through the river bed and set up camp the next evening. When our cars slid across the sand, questions poked through my head. Many early theories considered fairy circles to be scarred, explaining their appearance by poisoning or excessive collection of plants. Would it not be poetic if these, at first glance, dead sections turned out to be a stronghold of life?

* * *

Of course, there is another theory of the origin of fairy circles. Her pedigree begins in 1952, when British scholar Alan Turing sketched a mathematical platform to explain patterns found in nature. He showed that only a few equations can produce patterns that look like leaf curls, stripes of zebra or spots on the skin of a leopard.

Around the same time, when Jurgens put forward his hypothesis of sandy termites, explanations using Turing theories and not related to termites began to gain momentum in scientific journals. This process is called self-organization. Instead of a leopard skin, imagine a lonely piece of grass growing in the desert expanses of Namib.

Next to a piece of grass there is a shadow, as well as more moisture, because the grass emits some of it. Because of this, one or two shreds of grass grows next to it. The roots of these herbs grow in all directions, trying to drink someone else's water. Between healthy areas, the roots that spread everywhere suck out all the water, which creates patches of empty spots, which in computer simulations look exactly like circles of fairies.

“Fairy circles are generated by the availability of water,” says Stephan Getzin of the Center for Environmental Research. Helmholtz in Leipzig, who developed this interpretation of the origin of fairy circles, together with the Israeli environmentalist Yehud Meron and others.

According to their models, the pattern of fairy circles is based on the landscape features of a larger scale. Reducing the amount of precipitation over a grass lawn leads to the appearance of bald spots that resemble fairy circles, then to intricate patterns, then to individual scraps of grass. If you control this land, then the fairy circle may be the last warning: act immediately, as the last step of this sequence will be bare dunes.

From this point of view, the circles of Namib are just individual frames of the picture of the ongoing desertification, which unfolds not in time, but in space, from the wetter east to the drier west.

For Getzin, with his supporters, sandy termites are just one of many species that are often found in fairy circles. “Norbert Jurgens specializes in botany,” said Getzin. “If he could find these termites, then qualified or trained entomologists should also be able to find them.”

But Walter Tschinkel, a renowned expert on social insects who studied fairy circles for more than ten years, told me that when he excavated, sandy termites did not occur to him so often. Another entomologist, Eugene Marais, also failed to detect sandy termites in fairy circles.

From the point of view of Jurgens, this attitude "did not see termites, did not find termites" - an unpleasant thing. He argues that they are easy not to notice, and to break the sand must be carefully, with the help of blowers . To get out of this impasse, he instructed one of his graduate students to create a genetic test that can recognize the DNA of sandy termites in the sand gathered in a circle of fairies. While this test is under development.

Meanwhile, in the camp of supporters of self-organization, everyone was busy collecting evidence in favor of their version. They point to the orderly arrangement of the fairy circles as evidence that behind this phenomenon is Turing's mathematician, and not randomly working small bugs. They also showed that in landscapes with circles of fairies, water can move long distances horizontally - this is a necessary step to prove their theory of competition of grass tufts extending to long distances.

In 2016, Getzin and colleagues announced the discovery of another phenomenon, similar to fairy circles, and supposedly free from the actions of termites, located 10,000 km from Namib, in Australian wastelands. This announcement caused another war among scientists, in which Australian researchers claim that the spots of bare earth in the wastelands have already been described as a result of the action of local termites, with which the supporters of self-organization did not agree ... And away.

From the point of view of its supporters, self-organization provides a general mechanism for the appearance of regular patterns in plants all over the world. This is a comprehensive, albeit less romantic, solution to the mystery of fairy circles. “In science, there is such a thing as a story that is too good to give up on it, even when all the evidence points to the opposite,” said Chinkel. “I have a feeling that the thermite theory of fairy circles is one of those.”

* * *

So far, our caravan rather slowly approached our goal, the research site. First, all the students from Hamburg had a stomach flu. Then the wheel was unscrewed at Jurgens' car. But closer to the sunset of the third day of the expedition, we, squinting, cursing and bouncing on the bumps, reached out to Giribesvlakte - a huge plain filled with grass, eaten by cattle, in which there were so many fairy circles that it seemed that someone applied a form to cutting cookies out of dough.

We camped. Then Yurgens, in his habit of having done everything to everyone, began the sentence with the words “I offer”, proposing the team to split into several groups.

Kristin Lemke, a student working on a thesis, needed help in collecting data on the nests of ants located in fairy circles on Giribesvlakt. Felicita Gunter [Felicitas Gunter], who worked on her doctoral dissertation, went to excavate an entire trench between two adjacent circles, gently sweeping away the sand and marking out the scheme of the termites tunnels.

We are used not only to the sand that constantly creaks on our teeth, but also to a certain daily routine. The team went to work after breakfast. At lunchtime, the back door of one of the jeeps became the dining table, on which sausages, cheese and crackers were placed. After the next pair of sweatshops, we returned to the camp at the Leopard Stone, trying to get into the small shadows, clinging to the perimeter of this formation. When the air began to cool, we came back, finding ourselves in a violent wind blowing between the hot Namib and the cool Benguela Current running along the coast. Soon the sun was falling over the hills, and we changed into pants and sweaters.

One day at noon, I was near the Serpent, the only Namibian from the team, when he watched the group from the excavations. During the conversation, he pointed out to me a figure approaching us on the road, riding a donkey, behind which a herd of cattle was dragging around our jeeps. I asked if we could talk to this person about the circles. “We can try,” said Snake.He waved to the shepherd, and he stopped to wait for us until his flock moved further.

Coming closer, I realized that the shepherd was a teenager, a boy from the Himba tribe . He was wearing sandals, salmon-colored shorts and a pink American hoodie, over which a gray jacket was worn. Snake ran through the catalog of languages known to him, looking for a suitable one. Afrikaans ? English? Oshivambo ? No matches. Then the Serpent spoke in the language of Herero , and the boy answered in the adverb Himba. “He just says it's a formation from above,” said the Serpent. The boy called the fairy circle "okarupare", something like a vestibule, or a meeting place for groups of Himba men, as the Serpent explained.

The next day, the boy returned to the research camp, this time with a couple of friends. They were skeptical that small insects could be the cause of the whole set of circles. They said that circles are gifts of heaven. But Serpent showed them a small dug up nest, and explained the hierarchy of the colony, comparing it with the structure of the Himba tribe. He said that the workers eat in the nest, and in the other nest somewhere near the winged leaders and queens waited for the next rains. When plant growth resumes, these future royals may create their own circle of fairies, or take an abandoned one. The guys listened with great interest.

, . « », — , , , . , , , , . , , .

« 10 , , — . – , ».

* * *

Last year, suddenly, a third group joined the squabble over fairy circle. In Nature, a team that included Princeton environmentalist Rob Pringle and Corina Tarnita published a weird compromise : both sides of the argument are right. Just one slightly to the right.

Their own exploratory journey began in the fall of 2010, when a couple of post-docs met at dinner to discuss working together. Tarnita, the winner of various mathematical competitions in Romania, switched to ecology in the middle of training at the institute, and sent her mathematical firepower to criticize traditional evolutionary biology, which falls in the headlines. And at that moment she was in search of a new project.

. , . , , , , , , , .

. , , .

. , .

, – , – .

, , , . . , , .

Tarnita and Pringle told me that they had not even heard of fairy circles in Namibia before Jurgens published his idea of sandy termites. They became interested in this, and followed the media coverage of the disputes. They were confident that social insects could create large-scale structures. Other assumptions surprised them. “These guys say it's theoretically impossible,” Pringle said. - Of course available. And we will show that this is the case. ”

Last year, their team published their work, which paid tribute to self-organization, but mostly supported the theory of termites. Their computer simulations have shown that, although the grass is collected in small groups, termites are probably responsible for larger structures. The simulation results coincided with real air observations made in Namibia.

, , , , Nature, – , . , : . , , .

When we gathered around the campfire one cool evening in Giribesvlakte, Yurgens told us that last year his team and assistants visited four different locations with circles of fairies, from South Africa to the northwest of Namibia. In each of them, they chose 10 approximately equal circles of fairies, and then of them randomly chose 5 circles, which were unlucky. Then, with the permission of the government, they treated randomly selected circles with two chemicals that farmers use against termites.

Yurgens said he checked the results in Giribesvlakte a few weeks ago, and it was “quite clear” that there was much more grass growing in the treated circles than on the untouched ones - which supported his idea of termites as the reason for the presence of bare patches.

« , — , , . – , , . , , ».

* * *

. , . . , , . – .

, « » – , . , . 2016 , , – , . . « , — . – ».

, , . SASSCAL, , . , , , , .

. , , , , , .

1980-, , . , , .

, , , , . , . . – – , , , .

But today, all the shepherds for whom he fought, scattered around the nearby cities. The climate was against them, farming was no longer possible, and all of this reflected the larger trends observed by SASSCAL throughout the region. When Jurgens visited Richtersfeld this February, he checked out the plots that he had been observing for 38 years. Half of them left absolutely no plants. “Now I'm worried,” he said.

Mysterious fairy circles may contain part of a larger solution. Once, while in the Israeli desert of the Negev , Jurgens saw the ruins of the disappeared Nabatean kingdomwhose inhabitants built the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. In Nabatean architecture, stone structures redirected rare, but fierce rains of the desert into reservoirs, solving the problem in much the same way as, according to Jurgens, fairy circles operate.

It inspired him. Perhaps regions prone to drought may, for example, invest in the creation of water-collecting surfaces. “I have some ideas,” he said, “but maybe I will write them down for properly designed publications.”

Although this year the Giribesvlakte was dry and lifeless, the expedition was conducted not in vain. We observed the ants, caught the termites, rummaged in the mud. Poisoned some more fairy circles. And Yurgens happened to enlightenment in the fading light of the day, when he was picking in the sand of the megakrug next to the Leopard stone.

The next day I met him where he was digging the day before. There was growing a certain kind of grass, which he noticed, for the first time showing us mysterious mega circles. He made me get on my knees and put my hands in the sand, as he did, and feel how the roots are going down.

The problem of mega-circles, as he outlined it, is to explain their gigantic size and the presence of grass in the center of the islets, where usually there should be bare patches.

: , , , , , , - . , , , .

, ; . , , : «, ».

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/417447/

All Articles