How people "drowned" New Orleans

The center of New Orleans and the Mississippi River, in the foreground is the French Quarter , in the back West Bank , a photo from a drone. Authors: Lorenzo Serafini Boni / Emily Jan.

Because of the engineering work, "Crescent City" was below sea level. Now his future is at stake.

"Below sea level." Firstly, this is a well-known topographical fact about New Orleans, and secondly, the world's media to nausea often scoffed in a similar way after the impact of Hurricane Katrina in 2005. Locals usually mention this detail, combining a sullen smile with anxiety over the city.

In addition, it is only half true. The good news is, depending on where exactly the line is drawn, more than fifty percent of New Orleans’s agglomeration actually lies above sea level. The bad news is that before the “over” were one hundred percent, before engineers accidentally “drowned” half of the city. The intentions, of course, were good, and it was believed that this could solve one old problem. Alas, in return, created a new, and much larger scale.

')

Three hundred years have passed since the spring when French colonists began cutting down vegetation in order to found La Nouvelle-Orléans on a sparse, natural dam washed by the Mississippi River. Only three or five meters above the water's mirror, this piece of land was almost the only exalted place in the region, among swamps and swamps. Someone from the French then described it as "two narrow strips of land, the width of a musket shot, surrounded by impassable bogs and thickets of sugarcane."

After the foundation of New Orleans in 1718 for two hundred years, the city grew, and nothing remained but to master this meager coast - therefore, in local history, from urban and geographical names to architecture and infrastructure, many names echo the surrounding terrain.

New Orleans and its surroundings in 1863. A growing city lonely clings to the bend of the Mississippi River. Source: Wells, Ridgway, Virtue, and Co. / Library of Congress.

This may seem paradoxical to anyone visiting the Crescent City. What is the "relief"? We are in one of the most flat places in the region, how can we give so much importance to “hills”? But this, in fact, is the essence: the smaller the resource, the higher its value. Unlike other cities, where elevation drops can be tens of meters, in New Orleans the entire vertical meter can separate what was created in the time of Napoleon from what was built next door during the jazz era or the space age.

In order to understand how these features of the landscape grew and why they later “sank”, we are forced to go far into the past, straight into the Ice Age, where melting glaciers drove sedimentary deposits across the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico. About 7,200 years ago, the mouth of the river began to crush the sea, dumping the rock faster than tidal activity and currents could erode it. Nanos accumulated, and lower Louisiana gradually appeared on the Gulf coast.

The zones along the channel and tributaries turned out to be maximally elevated, because the largest amount of coarse-grained rock was deposited there. Farther from the river, mostly mud and clay fell, so here the soil only slightly rose above the level of the pestilence, turning into swamps over time. The farthest areas received scant doses of building material and, being among brackish tides, became wetlands or salt swamps. Under natural conditions, the entire delta of the river lay generally above sea level, from a few centimeters on the coast, to a few tens of meters in the bend of the river that formed the natural dam. Nature has built a lower Louisiana above sea level, albeit in part - and not for good.

Aboriginal people basically adapted to permanent flooding, strengthening their shores or moving to high ground during floods. But a little later, the Europeans arrived to colonize these lands. Colonization means constant presence, and consistency means engineering to stabilize this soft and moist landscape: dams to hold water, channels to drain the soil, and eventually, pumps to pump water from canals fenced off by flood control walls .

All this will need to be cultivated for decades and centuries to bring to mind. Until then, during the periods of colonial rule of France and Spain, and before Louisiana moved to American Dominion in 1803, the New Orleans had no choice but to cram into these two “narrow strips of land”, carefully avoiding the rest of the “impassable swamps and sugarcane ". People hated every inch of the swamp, seeing it as a source of putrid fumes, a cause of disease and a constant threat to prosperity. One columnist in 1850 described it this way: “This bubbling fountain of death is one of the most dreary, depressive and disgusting places over which the sun has ever shone. And all this, under tropical heat, belching poison and malaria ... a concentrate of seven Egyptian executions ... covered in yellow-green abomination. "

It was only much later that people learned that diseases like yellow fever are caused not by marsh fumes, but by the bites of mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti species carried with transatlantic voyages; that mosquitoes have proliferated due to urban drainage systems and low sanitation; that this “dull and depressed” locality has in fact helped to store water for centuries, from wherever it flowed - whether from the sky, Mississippi, Poncharthrain Lake or the Gulf of Mexico. And there is nothing "disgusting", just in those days, no one has yet lived in a swamp, as there was no drainage technology. And most importantly - this "yellow-green abomination" was above sea level.

Understanding perfectly well that urbanization doesn’t really fit in with the natural behavior of the river delta, in New Orleans they dug drainage canals and filled dams from the very day the city was founded. One of the colonists in 1722 said that the settlers were charged "to leave a strip of land no longer three feet wide in the area where the ditch should be dug in order to drain the soil." Diversion channels were made in order to speed up drainage back to the swamps, and they were dug in nearby plantations to control soil salinization or drain water to the mills.

The main driving force of these engineering structures, of course, was gravity, but in the early 1800s, steam energy came to the market. In 1835, the New Orleans Drainage Company began digging through a network of city gutters, and used the steam pumps to pump the effluent back into the St. John's duct - and even partially succeeded. A similar pumping system was built in the late 1850s, but the development of the initiative was interrupted by the Civil War. In 1871, the Mississippi and Mexican Gulf Ship Canal Company dug out about fifty miles of drainage, including three central drains, before bankruptcy.

It became obvious that the drainage of New Orleans is best done at public expense. In the late 1800s, state engineers tied together the cobbled bridges and gutters that had come down to them, added several steam pumps, and were thus able to divert about 40 millimeters of daily precipitation back to the surrounding waters.

Of course, this was not enough to drain the swamps, but enough to gradually raise the surface of New Orleans. We know this because in 1893, when the city finally decided to get down to business seriously and hired expert engineers to solve the problem, a heights scheme was created that had never been compiled before. The resulting topographic map of New Orleans (1895) can give an idea of the emergence of what would later become a world-class system.

Outline map of New Orleans, created in 1895 as part of attempts by city authorities to solve the problem of drainage. Source: Courtesy of the New Orleans Public Library

The map of 1895 also showed something curious: for the first time, the distant neighborhoods of some suburbs sank just below sea level. And such a drawdown did not promise anything good afterwards.

So began the anthropogenic lowering of the soil - the earth "sank" in the ground because of human actions. When the floods stopped and artificial dams restricted the spill, the groundwater level dropped, the soil dried, and the vegetation began to fade. After that, air pockets formed in the thick of the ground, where particles of clay, sand and salt gradually subsided, compressed - and pulled the city down.

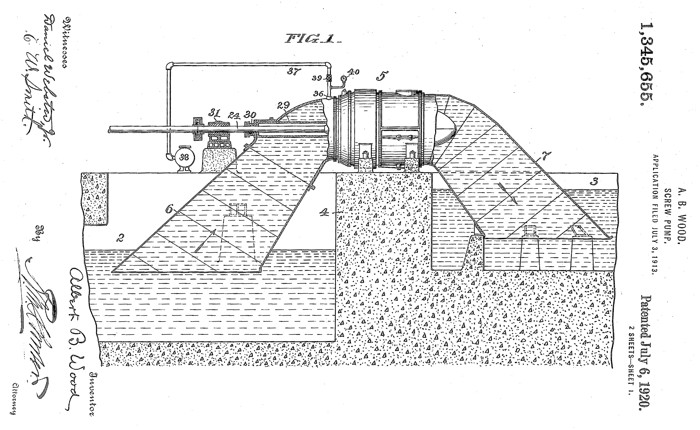

The construction of a new drainage system began in 1896 and already in 1899 was in full swing, as the new property tax was unanimously approved (note: two-mill property tax - taxed at $ 2 every thousand dollars of the market value of property. For example, if a property is valued at $ 4000, then a two-mill property tax will be $ 8) to create the New Orleans Sewerage and Water Board company. In 1905, about 60 kilometers of new canals and gutters were dug, hundreds of kilometers of pipes were laid and six pumping stations were built with a capacity of about 150 cubic meters of water per second. Radically, the efficiency of the system increased in 1913, when a young engineer, Albert Baldwin Woods, developed huge impeller pumps that could pump water much faster. Eleven "Woods screw pumps" installed in 1915, and most of them are still working. By 1926, about 120 square kilometers of soil were drained thanks to nearly a thousand kilometers of pipes and ditches, capable of draining about 370 cubic meters of water per second. New Orleans finally defeated swamp.

Urban geography has seriously changed. Within a decade or so, where the marshes used to be, a suburb appeared. Property prices skyrocketed, taxes swelled, and the city spread to lower reaches along Ponchartrain Lake. "All city organizations" celebrated a victory over nature, wrote John Magill, a local historian. "Developers encouraged expansion, newspaper workers glorified, the development planning commission sang ode to it, the city was built by trams to service it, and banks with insurers poured money on the river." The white “middle class”, passionately desiring to leave the old shabby suburbs, massively moved to new areas “on the shore of the lake”, not allowing black families to settle there through discriminating covenants .

Translator's Note

“For a long time covenants existed regarding racial minorities. The Committee on Civil Unity, in a publication from 1946, defined racially prohibitive covenants as follows: an agreement within the group of property owners, site developers or users of some real estate in a designated area, requiring them not to sell, rent or lease, or transfer to any other in the manner of their property to people with a certain race, color or creed, for a specified period of time; The only exception is the case of unanimous approval of such a transaction. ” Source: http://depts.washington.edu

And these places have already been rebuilt not on stilts above the ground, but on a stone foundation, rejecting two centuries of local architectural traditions. Why bother with flooding if technology has solved this problem?

Drawing screw Woods pump. Source: US Patent 1,345,655

Changes in the topography were small, but continuous. The whole city was above sea level in 1800, then only by 95 percent in 1895, and by 1935 only 70 percent was “above”.

Lowering the terrain continued the more, the more people moved to the lower reaches. In 1900, approximately 300,000 inhabitants lived above sea level, and when the population had grown to 62,725 people by 1960, only 48 percent remained “above”. At this point, about 321,000 residents lived in the former swamp, which had turned into a group of “bowls” with a bottom one or two meters below sea level.

To the average New Orlean of those years, this seemed like a kind of local "feature." And, as then, it is still unclear to many that the situation was not so long ago and solely due to the actions of a person, and there is a lot of danger in it. But the bridges are constantly jarring, and the buildings are cracking. In 1965, after the hurricane "Betsy" broke through the dam and flooded four urban areas, and the "feature" more began to resemble a "catastrophe."

Sinking of soil led to frightening consequences in the 1970s, when, without warning, at least eight who had no problems with the current maintenance of buildings took to the air. "To the majority of Metari residents," wrote The New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper, "It is extremely curious how long they lived for God knows how many time bombs." The area, which already initially lay low and was located mainly on the former peatlands, was drained just a decade earlier. A huge amount of "wet sponge" dried up, as a result, the soil "shrank" and caused the destruction of the foundations. And in some cases, the gas pipes were interrupted and the gas slowly leaked into the basements, after which there was just enough a small spark.

The emergency situation was smoothed out with the help of regulations requiring the use of pile foundations and flexible connections in communications supplies. But the larger problem only aggravated, because the gardens, streets and parks continued to subside, and those quarters that adjoined the surrounding reservoirs needed to be equipped with new drainage channels and anti-flood walls. Most of these systems, including those of federal significance, turned out to be unfinished, under-funded and under-verified, and too many of them did not withstand the impact of hurricane Katrina on August 29, 2005. The result of all this "topographic history" was sad when the sea broke through the barricades and flooded the cup-shaped areas with salt water, in some places to a depth of four meters. The massive loss of life and catastrophic destruction are the result of the fact that New Orleans was “below sea level”.

The elevation modeling in New Orleans, obtained with LIDAR , shows areas above sea level in red tones (up to 3 or 5 meters, except for artificial dams) and below sea level in tones from yellow to blue (mostly from -0.3 to -3 meters). Source: Richard Campanella / FEMA

What to do? Sinking of urban development will not turn back. Engineers and planners cannot “inflate” the compacted soil, if buildings are already built on them and people live. But they can reduce, and perhaps stop, the "sinking" of the terrain through slowing down the drainage of wastewater throughout the city in order to preserve as much water as possible on the surface, thereby feeding groundwater and filling the air cavities.

The idea of how such a scheme works is set forth, for example, in the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan , proposed by local architect David Waggonner in collaboration with colleagues from Holland and Louisiana. But even if such measures are to be carried out completely and completely, it is still impossible to lift those areas that have already sunk. Consequently, the agglomeration of New Orleans, along with the rest of the population of the country, must allocate funds for maintenance and improvement of barrier structures that prevent water from entering the “cup”.

To some extent, resources have already been received after Katrina, when the US Army Corps of Engineers quickly conducted the development and construction of a Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk-Reduction System (HSDRRS) system reducing the risk of damage from hurricanes and storms . Completed by 2011 and costing more than $ 14.5 billion, the complex or, as the locals call it, “The Wall”, stretching for many kilometers, was created with the aim of protecting the population even from floods of such a storm, which appear with a probability of no more than 1% in any arbitrarily selected year - even taking into account the fact that such a level of security is excessive, the system will continue to be improved.

Nevertheless, we know from history that the “walls” (that is, dams, embankments, flood walls and other solid barriers) caused problems with the relief in New Orleans, despite the fact that they were important for this. a three hundred year urban experiment in the Mississippi Delta. The city cannot rely only on such measures. The most important and important direction for ensuring a calm future in this region is support for structural changes in conjunction with non-structural approaches.

Since the 1930s, the Louisiana coast has been eroded over an area of more than 5,000 square kilometers, mainly due to the erection of the Mississippi River and the excavation of ditches for oil and gas pipes, as well as navigable canals - not to mention the rise in sea level and the salt invasion. water. To reduce losses can be due to the same property of the Mississippi River, which built this landscape; if the freshwater flow is diverted and the sediment transported by it is pumped to the coastal plain, this way you can squeeze the advancing salt water and strengthen the wetlands in less than the sea.

- , , «», «». , (Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, CPRA) , , . , 50 , . .

( ). , , , , . , Urban Water Plan, , .

, . , — , . « », , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/417189/

All Articles