The riddle with the neutron lifetime becomes more complicated, but dark matter is still not visible.

Two methods for measuring the life of a neutron give different results, which creates uncertainty in cosmological models. But no one knows what the problem is.

When physicists pull neutrons from atomic nuclei, shove them into a bottle and find out how many neutrons will remain in it after some time, they assume that neutrons experience radioactive decay after an average of 14 minutes 39 seconds. But when other physicists create neutron rays and count the number of protons that appear - particles that are products of the decay of free neutrons - they have an average lifetime of about 14 minutes 48 seconds.

')

Discrepancies between measurements in the bottle and the beam have existed since the methods for calculating the neutron lifetime began to produce results in the 1990s. At first, all measurements were so inaccurate that no one was worried about this. But gradually both methods improved, and still differed in estimates. Now researchers from the Los Alamos National Laboratory conducted the most accurate bottle measurement of the neutron lifetime, using a new type of bottle, eliminating possible sources of error inherent in previous schemes. The result, which will soon appear in the journal Science, reinforces the difference with measurements in experiments with rays and increases the chances of the emergence of new physics instead of a simple error in the experiment.

But what kind of new physics? In January, two theoretical physicists put forward an exciting hypothesis about the reason for this discrepancy. Bartoz Fornal and Benjamin Greenstein of the University of California at San Diego argue that neutrons can sometimes disintegrate into dark matter - invisible particles that make up six sixths of the entire matter of the Universe, taking into account their gravitational influence, and at the same time eluding during the decades of their experimental searches . If neutrons sometimes mysteriously turn into dark matter particles instead of protons, they must disappear from the bottle faster than protons appear in the rays - and this is exactly what happens.

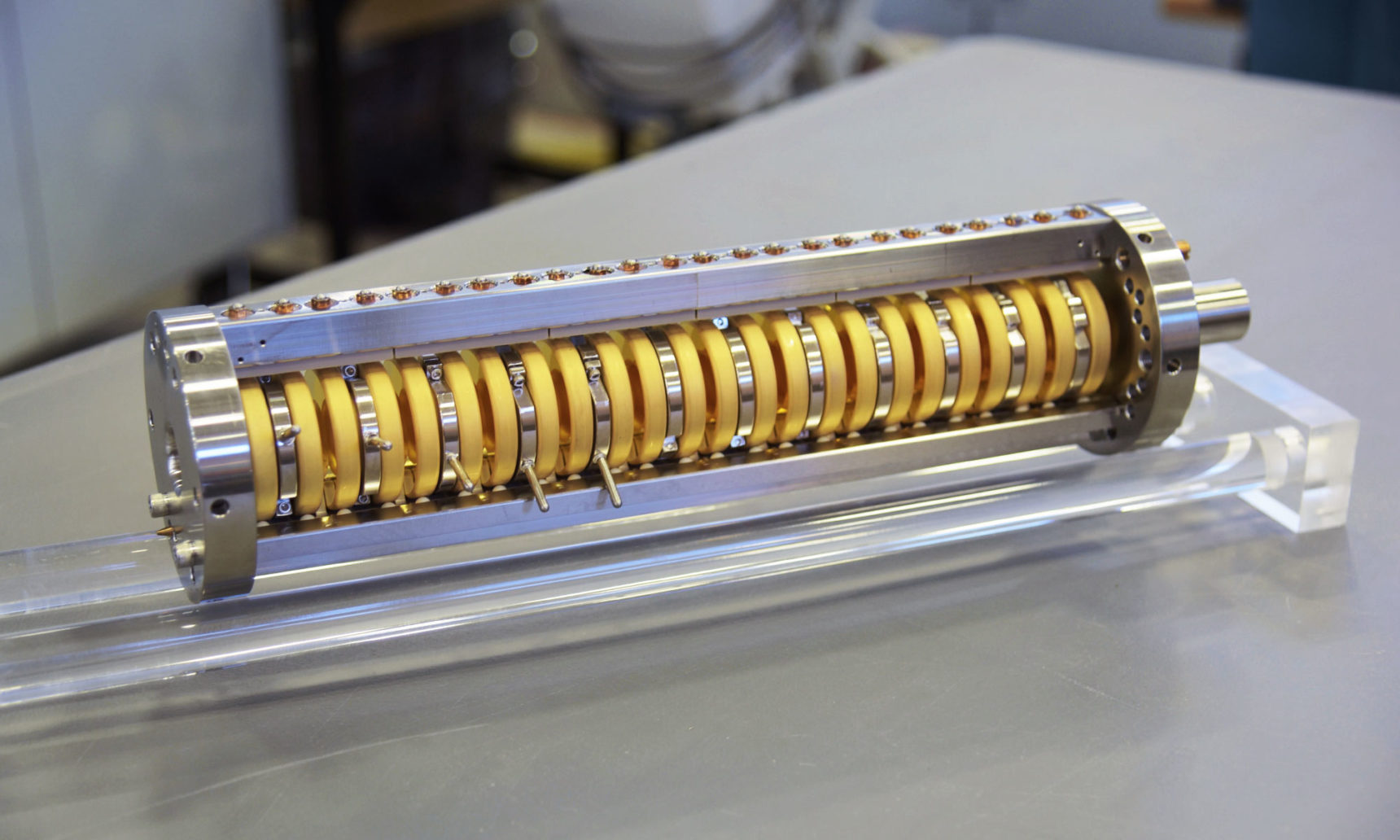

An UNCtau experiment in Los Alamos using the bottle method to measure the neutron lifetime

Fornal and Greenstein determined that in the simplest case the mass of a hypothetical dark matter particle must be within 937.9 - 938.8 MeV, and that a neutron decaying into such a particle will emit a gamma ray of a certain energy. “This is a very specific signal that can be searched for in experiments,” Fornal said in an interview.

The UCNtau experiment team in Los Alamos — named after ultracold neutrons and tau, a Greek letter for the neutron lifetime — heard about the work of Fornal and Greenstein last month when she was preparing for the next experimental approach. Almost immediately, Zhaowen Tang and Chris Morris, the collaborators, realized that they could screw the germanium detector to their bottle to detect gamma rays emanating from the decay of neutrons. “Zhao Wen went and made a stand, we collected the parts needed for our detector, placed them next to the tank and began collecting data,” said Morris.

Data analysis was also conducted quickly. On February 7, just a month after the appearance of the Fornal and Greenstein hypothesis, the UCNtau team reported the results of experimental tests on arxiv.org. They claim that they have eliminated the presence of characteristic gamma rays with a certainty of 99%. Talking about the result, Fornal noted that they did not completely rule out the dark matter hypothesis: there is another option in which the neutron breaks up into two dark matter particles, instead of a single particle and a gamma ray. But without clear experimental evidence, this option will be much more difficult to verify.

Proton detector at the National Institute of Standards and Technology used in the beam method

Evidence of the presence of dark matter is not found. However, the discrepancy in the neutron lifetime is established clearly as never before. And whether the neutron lives on average 14 minutes 39 seconds or 48 seconds, is of great importance.

Physicists need to know the neutron lifetime to calculate the relative amount of hydrogen and helium that appeared in the first minutes of the life of the Universe. The faster at that time the neutrons decayed into protons, the less they should have remained later when they were built into the helium nuclei. “The balance of hydrogen and helium is the first of many sensitive checks on the dynamics of the Big Bang,” said Jeffrey Green, a nuclear physicist at the University of Tennessee and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, “and he talks about how stars will form in the next billion years ”Because galaxies containing more hydrogen form more massive, and as a result, more explosive stars. Therefore, the neutron lifetime affects the predictions of the far future of the Universe.

In addition, neutrons and protons are composite elementary particles consisting of quarks held together by gluons. Outside of stable atomic nuclei, a neutron decays when one of its lower quarks experiences weak nuclear decay and turns into an upper quark, which turns a neutron into a positively charged proton and produces a negatively charged electron and an antineutrino. Quarks and gluons cannot be studied separately, therefore the decay of neutrons, as Green says, “is our best surrogate for studying the elementary interactions of quarks”.

A prolonged matter with nine-second uncertainty in the neutron lifetime must be resolved. But no one has a clue what the problem is. Green, a veteran of ray experiments, said: "We all carefully studied each other's experiments, and if we knew what the problem was, we would have found it."

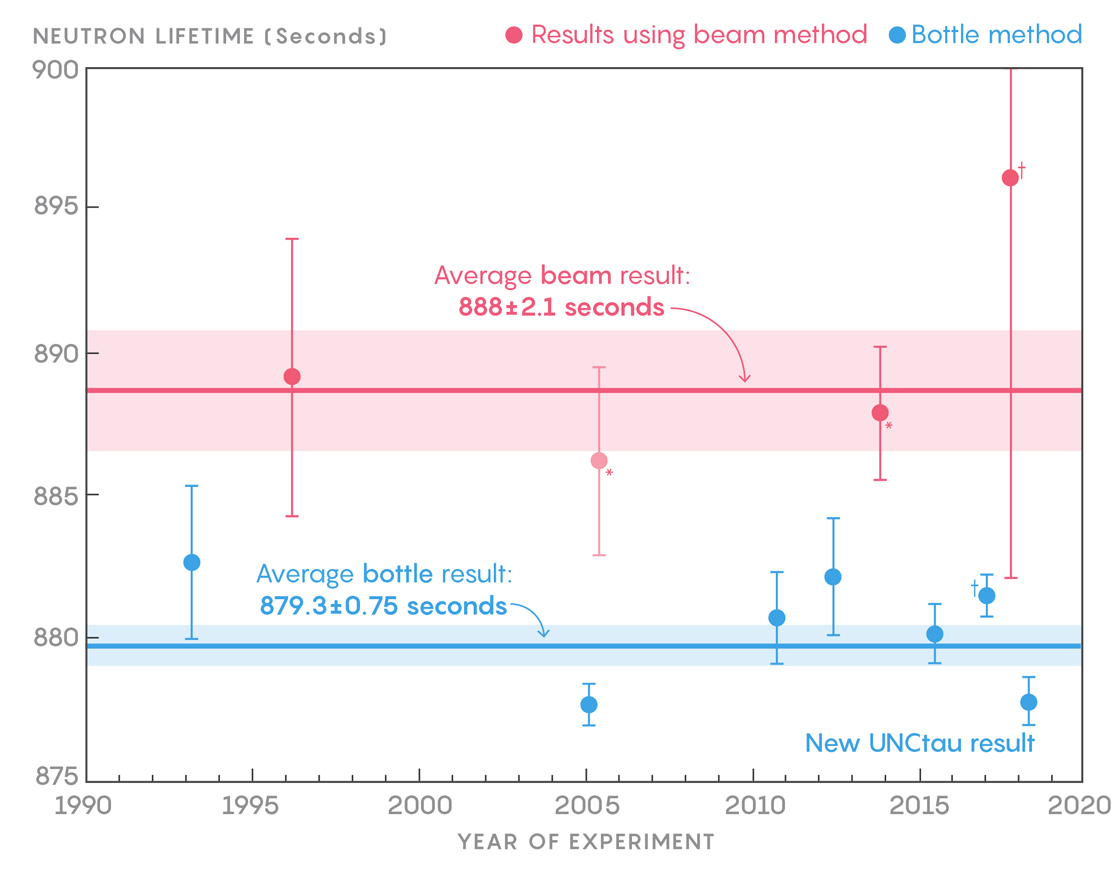

Vertical - neutron lifetime in seconds. Red marked the results of experiments with rays, blue - with bottles.

For the first time, the discrepancy became a serious problem in 2005, when a group led by Anatoly Serebrov from the St. Petersburg Institute of Nuclear Physics and Physics from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Gaithersburg, Maryland, reported, respectively, the results of measurements by bottles and beams, very accurate for themselves - the bottle error was estimated at one second, and the radiation one at three seconds - but differing from each other by eight seconds.

After a lot of improvements in work patterns, independent checks and thoughtful scaling of scientists' heads, the difference between the average time for the bottle and the beam only slightly increased - up to nine seconds - and the errors decreased. It turns out two options, as Peter Geltenbort, a nuclear physicist from the Laue-Langevin Institute in France, who worked as a member of Serebrov’s team in 2005, and now works at UCNtau, says: “Either we have some rather exotic new physics, or we all overestimate the accuracy measurements.

Practicing rays scientists from NIST and other laboratories worked to understand and minimize the many sources of uncertainty in the experiments, including the intensity of the neutron beam, the volume of the detector through which it passes, the efficiency of the detector perceiving the protons generated by the decaying neutrons along the entire length of the beam. Over the years, Green was especially skeptical about measuring the intensity of a beam, but independent checks removed doubts. “Now I don’t have a better candidate for the systematic phenomenon we overlooked,” he said.

As for the bottles, experts suspected that neutrons could be absorbed by the walls of the bottles, despite covering them with a smooth and reflective material, even after adjusting the absorption through changing the size of the bottles. In addition, something can skip the standard way of counting the number of survivors in a bottle of neutrons.

But the new experiment in UCNtau ruled out both explanations. Instead of storing neutrons in material bottles, scientists caught them with magnetic fields. Instead of moving the surviving neutrons to an external detector, they used a local detector, immersed in a magnetic bottle and quickly absorbing all the neurons inside. Each absorption is characterized by a flash of light, which is registered by photocells. However, their final result supported the results of previous experience.

It remains only to move on. “Everyone moves on,” said Morris. He and the UCNtau team are still collecting data and finishing the analysis, which includes twice as much data as in the work that will soon appear in the journal Science. They intend to measure tau with an error of just 0.2 seconds. As for the rays, a group from NIST, led by Jeffrey Niko, is collecting data now and expects results to appear within two years, and the error will be limited to one second — while his experiment, J-PARC, is underway in Japan.

NIST and J-PARC will either confirm the result of UCNtau, forever determining the neutron lifetime, or this saga will continue.

“The improvement of experiments is motivated by this tension created by the discrepancy in two independent methods,” said Green. If only one of the technologies had been developed, a bottle or a ray, physicists would be able to proceed with the wrong value for the tau built into their calculations. “The advantage of owning two independent methods is that they maintain honesty. When I worked at the National Bureau of Standards, the saying went: “A person with one watch always knows exactly what time it is; a man with two hours is never sure of that. "

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/411139/

All Articles