Neutrinos offer a solution to the mystery of the existence of the universe

The updated results of the Japanese experiment with neutrinos continue to reveal details of inconsistencies in the behavior of matter and antimatter.

Neutrinos passing through the Super-Kamiokande installation create an informative color distribution on the detector walls

If you look from above, you can confuse a hole in the ground with a huge elevator shaft. But in fact, it leads to an experiment that can answer the question of why matter did not disappear, turning into a cloud of radiation soon after the Big Bang.

I am in the Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex (Japan Proton Accelerator Research Complex, J-PARC ) - a remote and well-guarded government agency in Tokai, about an hour by train north of Tokyo. The T2K experiment running here ( Tokai-to-Kamioka ) produces a beam of subatomic particles, the neutrino. The beam passes through 295 km of stone to the detector of the Super-Kamiokande, a giant pit buried at a depth of 1 km under the ground and filled with 50,000 tons of ultrapure water. During the journey, some neutrinos change the "grade" from one to another.

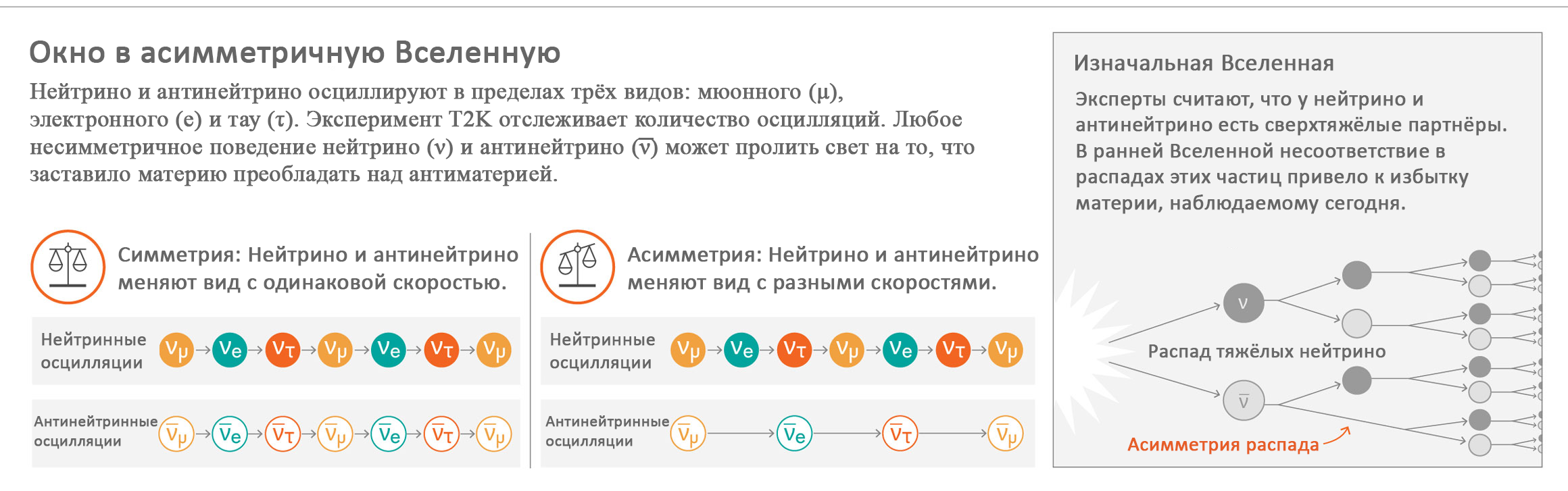

The experiment continues today, and its first results were made public last year. Scientists at T2K are studying how neutrinos change grade, trying to explain the predominance of matter over antimatter in the Universe. During my visit, the physicists explained to me that they were processing the new data obtained over the last year, and the results were promising.

')

According to the Standard Model of particle physics, each particle has its mirror partner, which carries the opposite electric charge - the antimatter particle. When particles of matter and antimatter collide, they annihilate in a flash of radiation. However, scientists believe that during the Big Bang an equal amount of matter and antimatter should have appeared, which would mean that everything should have disappeared rather quickly. But it did not disappear. A small fraction of the original matter survived and formed the known Universe.

Researchers do not know why this happened. “There must be some particle reactions that occur differently in matter and antimatter,” says Morgan Vasco, a physicist at Imperial College in London. For example, antimatter can disintegrate differently from matter. If so, it would violate the idea of CP-invariance , which postulates that the laws of physics should not change if we replace matter particles with antiparticles (symmetry with respect to charge) and mirror them (parity symmetry). Symmetry is performed for most particles, but not for all. Subatomic quark particles violate CP symmetry, but the deviations are so small that they are not enough to explain why matter dominates so much over antimatter in the Universe.

Last year, the T2K collaboration announced it had received the first evidence that CP-invariance could be violated by neutrinos, which could potentially explain why the Universe is filled with matter. “If there is a violation of CP-invariance in the neutrino domain, this can easily explain the difference between matter and antimatter,” said Adrian Bevan, a specialist in particle physics from Queen Mary University of London.

Researchers are looking for CP-violation, studying the difference in the behavior of matter and antimatter. In the case of neutrinos, scientists with T2K study how neutrinos and antineutrinos oscillate , that is, change, on the way to the Super-K sensor. In 2016, 32 muon neutrinos were changed to electronic ones on the way to Super-K. And when the researchers sent muon antineutrinos there, only four of them became electronic.

The results obtained shook the community - although most physicists did not fail to point out that with such a small sample there was a 10% chance that this difference was the result of random fluctuations (for comparison, when the Higgs boson was discovered in 2012, the probability of a random signal was one millionth).

This year, researchers have collected nearly twice as much neutrino data as in the past. Super-K caught 89 electron neutrinos, and this number greatly exceeds the threshold of 67 particles, which were supposed to appear in the absence of violation of CP-invariance. The experiment also found only seven electron antineutrinos, two less than expected.

While researchers do not announce the discovery. Due to the not very large amount of data, "there is still 1 chance out of 20 that this is a statistical deviation, and not a violation of CP invariance," says Philip Lichfield, a physicist at Imperial College in London. To make the results really meaningful, adds this, the experiment must go up to 3 chances out of 1000, and researchers hope to overcome this line by the mid-2020s.

But the data improvements made last year, albeit modest, still go “in a very interesting direction,” said Tom Browder, a physicist from the University of Hawaii. Hints of a new physics have not yet disappeared, as one would expect if the results obtained were written off to the case. They also add the results of another experiment, NOvA, conducted at the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in a suburb of Chicago. Last year, he released the first set of neutrino data, and antineutrino results are expected next summer. And although these first results on violation of CP invariance will not be statistically significant either, if the results of the NOvA and T2K experiments coincide, the “consistency of all these early hints” will be quite intriguing, says Marc Monsieur, a physicist at Indiana University.

The planned update of the Super-K detector may spur research. The next summer, water is pumped out of the detector for the first time in a decade, and then re-filled with ultrapure water. It will be mixed with gadolinium sulfate, such a salt, which should significantly increase the sensitivity of the device to electronic antineutrinos. “Adding gadolinium will make the detection of electron antineutrino interactions a very easy task,” said Browder. Salt will help researchers to isolate antineutrino interactions from neutrino interactions, which will increase their ability to search for CP-violation violations.

“So far, we are ready to argue that CP invariance is violated in the case of neutrinos, but we won’t be surprised if this is not so,” said Andre de Guvea, a physicist at Northeastern University. Vasco is a little more optimistic: “The results of the 2017 T2K have not yet clarified our understanding of CP invariance violation, but promise to increase the accuracy of its measurement in the future,” he said. “And, perhaps, the future is no longer as far as we could have thought last year.”

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/410869/

All Articles