Do not believe what they write about nutrition

Love for a cabbage tied with a navel in the form of hollows

At the end of each year, millions of people swear to change their eating habits. Usually, people divide food into moralistic categories: good / bad, healthy / unhealthy, nutritious / tasty, for weight loss / complete - but opinions about which food belongs to which of these categories diverge.

The Nutrition Advisory Committee of the United States recently released a new set of recommendations that defines a healthy diet as a diet that emphasizes vegetables, fruits, uncooked grains, low-fat foods, seafood, legumes, and nuts, and reduces the content of red and processed meats, refined grains, and sugar-containing foods and beverages. These recommendations immediately caused a storm of disputes . An editorial in the medical journal BMJ concluded that there was a lack of rigorous evidence ; This statement was actively disputed by members of the committee.

Some cardiologists recommend the Mediterranean diet rich in olive oil, the American Diabetes Association supports both low-carbohydrate diets and low-fat diets, and the Doctors Committee for Responsible Medicine promotes vegetarianism. Ask a smart crossfit fan, and he will recommend you a " paleodiet " based on what our ancestors in the Paleolithic supposedly ate. My colleague Walt Hickey advocates a ketogenic diet .

')

Who is right? It is hard to say. On the issue of nutrition, everyone has their own opinion. But no one has solid evidence. Problems begin because there is a lack of agreement about what makes a diet healthy. Weight reduction? Muscle building? Maintaining bone strength? Preventing heart attacks, cancer, dementia? Whatever you worry about, we will not have a lack of special diets designed to help you. To link food habits and addiction to food with health factors is easy to ridiculous - as you will soon see from a small experiment conducted by our editorial board.

Consumption of egg rolls associated with the presence of a dog in the family

Our intrusion into the field of nutritional science has demonstrated the depressing state of articles written on the effects of food on health. As proof, we will take you backstage and show how this research is conducted. The first thing to keep in mind is that nutritional researchers are studying an extremely difficult problem, since it is impossible to find out what people eat and in what quantities, unless they are locked up in a room under supervision. Therefore, almost all nutrition studies are based on measurements of food consumption according to reports of the people themselves, who need to remember what they ate. The most common ways of such a calculation are food diary, memory quizzes and food consumption questionnaires [food frequency questionnaire, FFQ].

There are several options for ready-made FFQ, but the technique is the same for everyone: you need to ask people how often they eat certain foods and in what quantities. It’s not always easy to remember everything you ate, even if it was yesterday. People usually underestimate the amount and variety of food eaten, they may not admit that they ate something or calculate the wrong amount of food.

“As a result, it turns out that it is very hard to conduct research related to diet,” says Torin Block , CEO of NutritionQuest, the company that conducts the survey. The company was founded by his mother, Gladys Block , a pioneer in this field who began to develop FFQ at the National Cancer Research Institute. “There is no way to get rid of mistakes.” And yet, according to him, there is a certain hierarchy of similar questionnaires for completeness. Food diaries are rated quite high, and with them - daily polls, in which the administrator interviews the subject, and compiles a catalog of everything he has eaten in the last 24 hours. But, as Blok says, "it is necessary to conduct several such sessions in order to get a complete picture of the average person's diet." Researchers are usually not very interested in what people ate yesterday or the day before — they need to know what they eat regularly. Studies using daily polls usually underestimate or overestimate the impact of food that people do not eat every day, because they record a small and unrepresentative period of time.

When I tried to keep a consumption diary, I discovered how right Blok was - it is amazingly difficult to make a picture of food habits using data collected over several days. It so happened that I went to the conference that week, so I ate dry snacks and ate in restaurants, which is very different from homemade food. My diary showed that one day before dinner I only ate a donut and two packages of chips. And what did I have for dinner? It was a delicious curry from Indonesian seafood, but I would not be able to list here all the ingredients.

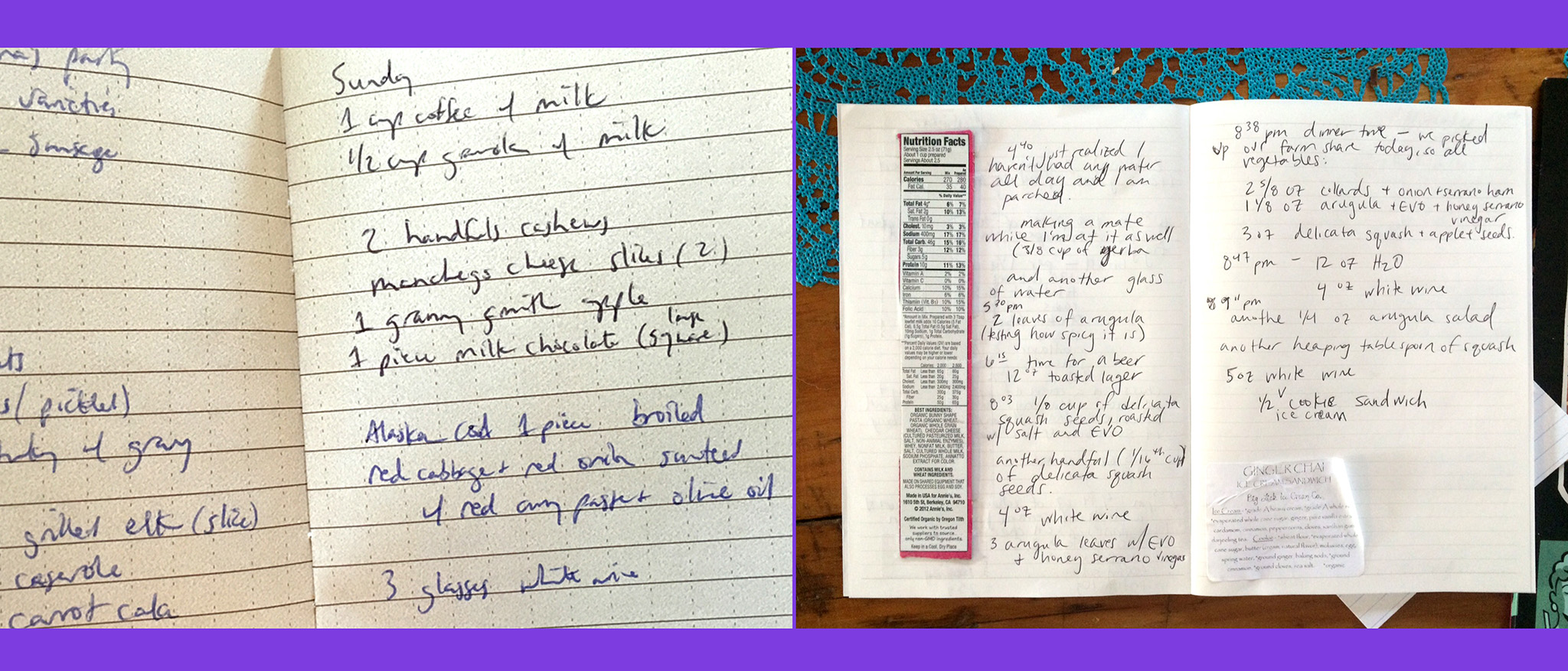

Food Diary Pages

Another lesson I learned from short-term diary - the process of tracking consumption can affect what you eat. When I knew that I would have to write it down, I was much more attentive to what I was eating, and sometimes as a result I did not eat something because I was too lazy to write it down, or because I understood that I did not I need a second donut (or I did not want to admit that I ate it).

It is difficult to deceive an instinct that requires lying about eating food, but FFQ seeks to overcome the unrepresentativeness of nutritional short records, assessing what people consume for longer periods. When you read an article with a text like " blueberries prevent memory loss, " then the evidence was most likely taken from some FFQ. The questionnaire usually asks what the respondent has eaten in the past three, six, or 12 months.

To understand how these surveys work and how reliable they are, we hired Blok to try out a 6-month questionnaire from their company on me, my colleagues Anne Barry-Jester and Walt Hickey, as well as a group of volunteers.

Some questions - how often do you drink coffee? - were pretty simple. Others stumped us. Take at least tomatoes. How often have I eaten them for six months? In September, when there were plenty of them in my garden, I ate cherry tomatoes like a candy child. Maybe I ate 2-3 Cherokee tomatoes with vinegar and olive oil per day. But at the same time, from November to July, I could not eat tomatoes at all. And how can I answer this question?

Questions about the volume of food puzzled everyone. In some cases, the survey gave us unusual, though useful, tips — for example, it showed an approximate volume of half a cup, a whole cup, and two cups of yogurt using photographs of cups filled with sawdust. Other questions seemed absurd. “Who knows what a cup of salmon meat or two cups of pork ribs looks like?” Walt asked.

Although the questionnaire simply had to measure how much food we consumed, sometimes it seemed that there was criticism in the questions - do we drink full fat milk, low fat milk or skimmed milk? I noticed that when choosing from three options for the volumes of dishes I always wanted to choose the average, regardless of the actual size of my portions.

Despite these difficulties, Anna and Walt and I did our best to answer honestly and most fully. After that, we compared the results. The survey showed that fatty cheese and different types of alcohol were our main sources of calories.

Further, our diets are divided. Walt lost 25 kg on a ketogenic diet, Anna eats quite a bit of protein, and I, according to FFQ, consume almost two times more calories than each of them.

Can these results be true? Anna and I are almost the same height and weight; we could probably share clothes with each other. How can I eat twice as many calories as she? Blok acknowledged that it’s difficult to calculate calories accurately, especially without food records for a long period of time, and if you start to understand individual nutrients, it is still more confused. He referred to a study from 1987 , according to which in order to fully assess the average calorie intake, it is necessary to collect data on nutrition daily for an average of 27 days for men and 35 days for women. And some nutrients are even harder to track down - for example, it takes 474 days to evaluate vitamin A in women. This suggests that our reports may be correct, or they may contain a lot of errors.

Love for chips tied with good results in mathematics

Of course, measurements that rely on memory have their limitations, ”says Brenda Davey , a professor of human nutrition at the Virginia Technology. "But most of us nutritionists believe they have value." Calories are harder to measure, she says, noting evidence that people underestimate the amount of food they eat that they consider unhealthy , such as fatty foods or sugary foods. “But this does not mean that they underestimate all indicators. This does not mean that there are problems with the measurement of eaten fiber or calcium. "

The developers of the questionnaires understand that the answers are not perfect, and they try to correct them with confirmatory studies that verify data from FFQ with data obtained by other methods — usually a survey on food taken in the last day or a consumption diary for a longer period. The results of confirmatory studies, according to Blok, allow researchers to take into account the variability of daily consumption.

Critics of FFQ, for example, Edward Archer , a specialist in computational psychology at the Center for Nutrition and Obesity Research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, said that these confirmatory studies are just arguments that do not go beyond the logical circle . “You take one type of subjective report and confirm it with another type of subjective report,” he says.

Writing down everything you eat is harder than it seems, says Tamara Melton, a nutritionist and official at the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics in Atlanta. Among other things, it is almost impossible to measure the ingredients and portion sizes when you are not at home. "It is not comfortable. If you're at a business lunch, you won't get your measuring cup. ”

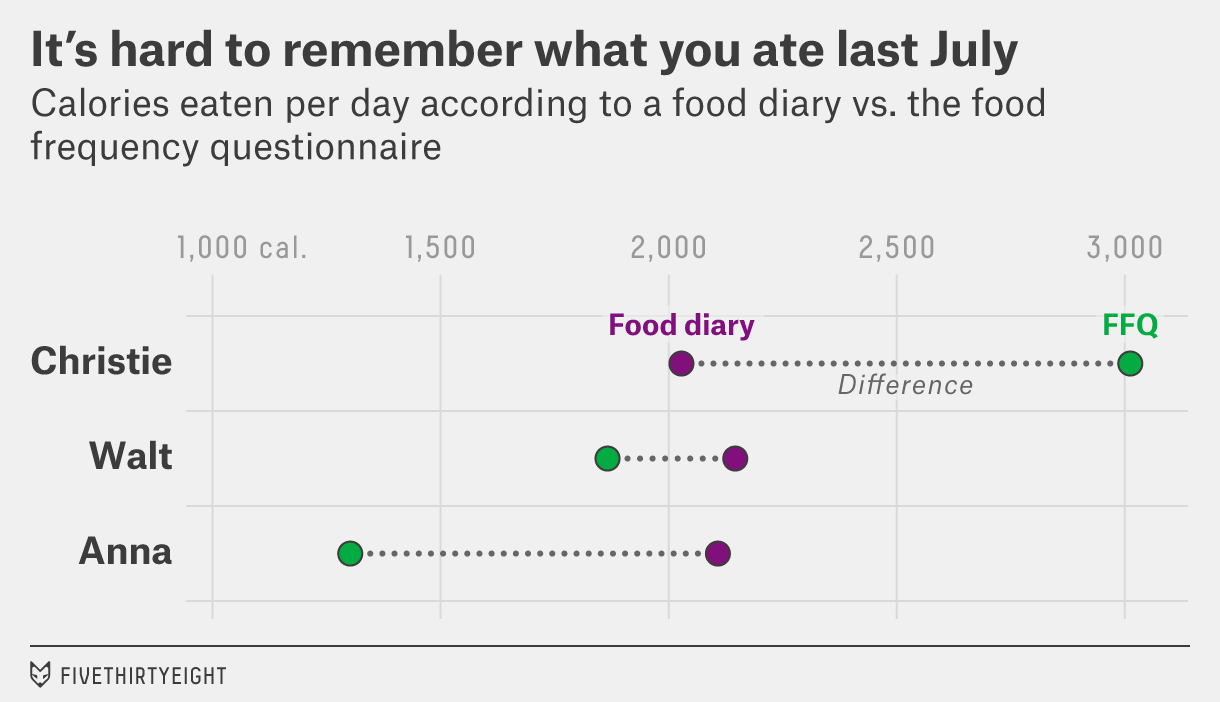

When Anna and Walt and I compared the calorie intake according to our FFQ with what we calculated due to our weekly consumption diaries, the results did not match. We hardly figure out the sizes of our portions for FFQ, and who knows which of the results was more accurate?

Difference in estimating calorie intake according to FFQ (green) and consumption diaries (purple)

And although doubts about the accuracy of self-assessments of food consumption have existed for decades, this debate has recently intensified, according to David Allison , director of the Research Center for Nutrition and Obesity at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Allison was the author of the 2014 expert report compiled by the working group on energy balance measurement, in which the use of “definitely inaccurate” measurement methods was called “unacceptable” for developing health care strategies, research and clinical practices. “In this case,” the researchers wrote, “the dictum“ at least something is better than nothing ”must be changed to“ at least something worse than nothing ”.”

Problems with questionnaires even deeper. They are not just unreliable, they give out huge amounts of data with many variables. The final cornucopia of possible combinations of variables makes it too easy to adjust them to beautiful and incorrect results , as we learned by inviting readers to go through FFQ and answer a few questions about themselves. We received 54 complete answers and looked for connections between the data in them - just as researchers are looking for links between food and dangerous diseases. Finding such connections was ridiculously easy.

Our shocking new research has found that

| Consumption of products like | Associated with | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Raw tomatoes | Judaism | <0.0001 |

| Egg roll | Having a dog | <0.0001 |

| Energy drinks | Smoking | <0.0001 |

| Potato chips | Good math grades | 0.0001 |

| Soda | Strange rash over the past year | 0.0002 |

| Shellfish | Right-handedness | 0.0002 |

| Lemonade | Confidence that the movie " Collision " was to receive an award for the best motion picture | 0.0004 |

| Breaded Fried Fish | Democratic Party Membership | 0.0007 |

| Beer | Frequent smoking | 0.0013 |

| Coffee | Having a cat | 0.0013 |

| Salt | A good impression about the work of the Internet provider | 0.0014 |

| Low-fat steak | Secularism | 0.0030 |

| Tea with ice | Confidence that the movie " Collision " did not deserve an award for the best motion picture | 0.0043 |

| Bananas | Good grades for reading | 0.0073 |

| Cabbage | Navel in the form of a hollow | 0.0097 |

Our FFQ issued 1066 variables, and additional questions sorted the respondents according to 26 possible characteristics (for example, right-handed or left-handed). This large amount of data allowed us to build 27,716 regressions in just a few hours (full results can be viewed on GitHub ). With such a set of possibilities, we were guaranteed to find “ statistically significant ” correlations unrelated to reality, says Veronica Wieland , a statistician who runs the Battelle Center for Mathematical Medicine at the National Children's Hospital in Columbus, pc. Ohio. Using a p-value of 0.05 or less to measure statistical significance is equivalent to an error of 5%, says Wiland. And with 27,716 regressions, 1386 false-positive results can be expected.

But false positives are not the only problem. According to Wieland, there was a high probability that we would find real correlations, which are useless from a scientific point of view. For example, our experiment found that people who cut off fat from a steak were more likely to be atheists than they thought that fat is a gift of God. It is possible that this correlation is real, says Wieland, but this does not mean that it expresses a link between cause and effect.

A preacher who advises parishioners not to cut off fat from meat, in order not to lose faith, can ridicule, but nutrition epidemiology experts often make recommendations based on such unreliable evidence. A few years ago, Jorge Chavarro , a nutrition epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health, recommended that women trying to get pregnant switch from low-fat foods to fatty foods , such as ice cream, based on data obtained from FFQ during a nursing study . They and their colleague Walter Willet also wrote a book promoting the " fertility increase diet " based on this data. When I contacted Chavarro to ask how confident he was about the connection between diet and fertility, he said that “of all the connections we found in this, we were the least confident.” And of course, it was she who hit the headlines.

Virtually any product that you can imagine is associated with any health effects in peer-reviewed research papers and tools such as FFQ, says John Ioannidis , expert on reliability of research results from the Center for Innovations in Meta Research at Stanford . In an analytical paper from 2013 , published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Ioannidis and colleagues randomly selected 50 common cookbook products and found studies assessing the relationship of each of them to the risk of cancer. It turned out that research found a link between 80% of products - including salt, eggs, butter, lemons, bread and carrots - and cancer. Some of them pointed to an increase in the risk of cancer, others to a decrease, but the health effects of these products were “exaggerated to the point of impossibility,” says Ioannidis, with a weak evidence base.

Foods that increase or decrease the risk of cancer. Estimates are given for 20 products, each of which has been studied in at least 10 studies.

But the problems are not only statistical. According to Ioannidis, many of the research results were biologically unlikely. For example, in a 2013 study, it was found that people who consumed nuts three times a week reduced mortality by 40%. And if the nuts really did reduce the risk of death so much, it would be a revolutionary discovery, but this number is almost certainly greatly exaggerated, as Ioannidis told me. And without context, it does not make sense. Will a 90-year-old get the same benefits as a 60-year-old? How many days or years does the nut diet need to be maintained in order for its effect to turn on, and how long will it last? It is to these questions that people want answers. But as shown by our experiment, it is very easy to use nutrition surveys to link products with some results, but it is very difficult to understand what these links mean.

FFQs are “not perfect,” Chavarro said, but for today there are almost no other options. “We may have reached the limits of the current nutritional assessment methodology, and a significant shift will be required to improve results.”

Current research has another fundamental problem: we expect too much from them. We want to answer questions like what is better for health - butter or margarine? Will eating blueberries keep my mind in good condition? Will I have bowel cancer due to bacon? , , , .

, , . . – , , , . , ( , ). , , 10000 , , , 10000 , , . – 0,01% 0,03% — , , .

, , , , . « », – 2013 .

: ? – , . . , , , , . « , , », – . , , . , , , , , .

, , . , . , , . – . , . , , . , , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/405461/

All Articles