Burning modern version of the Library of Alexandria

Ulm Wiblingen Abbey Library

You should have had the opportunity to access the full text of almost any book ever published in one click. For books published so far, you would have to pay, but everything else — and this collection would grow faster than the archives of the Library of Congress, Harvard, the University of Michigan, or any of the European national libraries — would be available completely free of charge through terminals installed in any library that would like to.

Through the terminal one could search for tens of millions of books and read any page of any found book. It would be possible to select text, leave notes and share them. For the first time, it would be possible to point out any idea stored among extensive printed records and send someone a link to it. Books would be available instantly, with search, copying, and they would be as alive in the digital world as web pages.

')

This was to be the realization of a long-cherished dream. “People have talked about universal libraries for thousands of years,” says Richard Ovenden, head of the Oxford Bodlian libraries . “During the Renaissance, it was possible to imagine an opportunity to collect all the published knowledge in one room or in one institution.” In the spring of 2011, it seemed that we had collected this collection in a terminal that could fit on the table.

“This epoch-making achievement can serve as a catalyst for reinventing education, research, and intellectual life,” one enthusiastic columnist wrote at the time.

But on March 22 of that year, a bill that would open access to books printed over a hundred years and showered all countries with access terminals to the universal library was rejected under rule 23 (e) (2) of the civil code by the US District Court of the Southern District of New York .

The destruction of the Library of Alexandria in the fire called "international catastrophe." And when the most important humanitarian project of our time was rejected by the court, many humanists, archivists and librarians who took part in this process, sighed with relief, because at that time they believed that they barely managed to avoid a catastrophe.

* * *

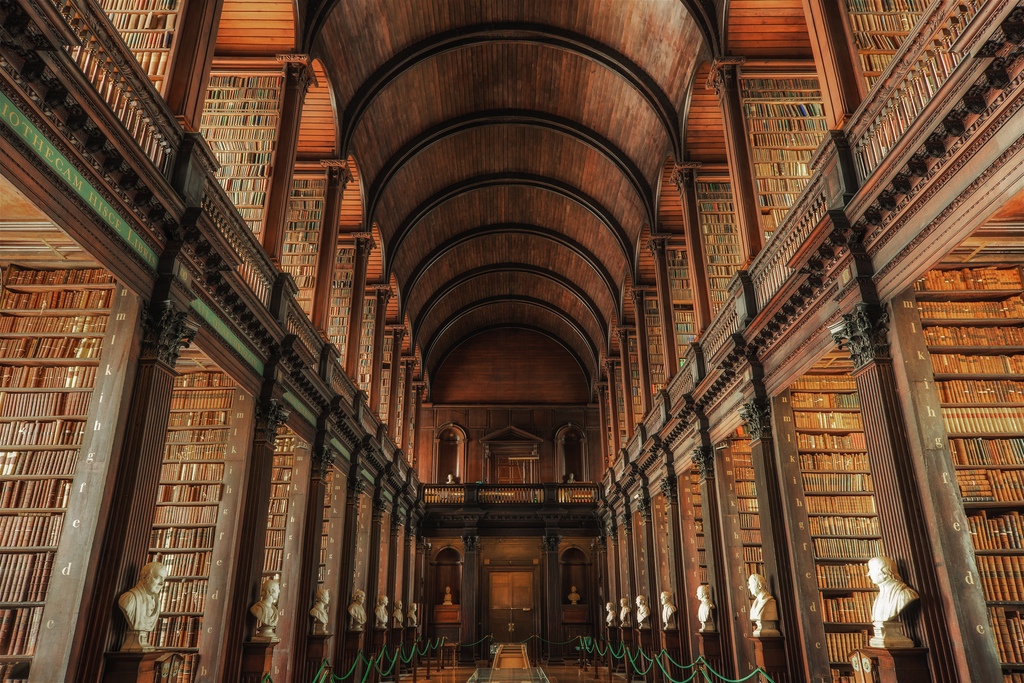

College Library of sv. Trinity, Ireland

Google’s secret project to scan all the books of the world, codenamed “Project Ocean,” really began in 2002, when Larry Page and Marissa Mayer met in a room that also had a 300-page book and a metronome. Page wanted to know how long it would take to scan more than one hundred million books, and he began his research with the ones he had on hand. Using the metronome to maintain the rhythm, he and Mayer flipped through the book from cover to cover. It took them 40 minutes.

Page has always dreamed of digitizing books. Back in 1996, his student project, which would later become Google - a crawler, digesting documents and assigning them rank by relevance regarding a user's request - was conceived as part of a project to “develop technologies for a single, integrated, universal digital library”. The idea was that in the future, when all the books will be digitized, you could mark up their quotes, look at which of them quote most often, and use this data to improve the search results conducted by librarians. But the books mostly lived on printed pages. Page with his research partner, Sergey Brin , developed his idea of a “popularity contest for the number of quotes” using Internet pages.

In 2002, Page decided that it was time to return to the books. Keeping in mind a 40-minute period of time, he went to the leadership of the University of Michigan, his alma mater and world leader in scanning books, to find out what the advanced technologies of mass digitization look like. At the University of Page, it was reported that with the current speed, the complete digitization of their collection of 7 million volumes will take about a thousand years. Paige, who had thought of this task by then, said that he was sure that they would cope with Google in six.

He offered the library a deal: you allow us to borrow books from you, and we scan them for you. You will have digital copies of all the books in your collection, and Google will have access to one of the great storehouses of knowledge, access to which is so far closed to all. Bryn described the thirst for books in this way: "You have thousands of years of knowledge of mankind locked in your books, and, perhaps, knowledge of the highest quality." What if you could feed all the knowledge locked on paper to a search engine?

By 2004, Google began scanning. In just ten years, agreeing with Michigan. Harvard, Stanford, Oxford, and the New York Public Library, as well as dozens of others, the company overtook Page's prediction by scanning 25 million books. On this, they spent about $ 400 million. And this was not only the achievement of technology, but also logistics.

Every weekend, wagons with books stopped at special Google scanning centers. The Stanford Library digested the center on a Mountain View campus located in a former office building. The books were unloaded from the trucks to the library carts, and delivered to the human operators sitting behind several dozen scanning stations, arranged in rows 2-3 meters apart from each other.

The stations, which were not actually scanned, but photographed books, were built by the company from scratch. Each could digitize books at a speed of 1000 pages per hour. The book was lying on a mechanical stand that adjusts to the spine and fixes it in place. Above it was an array of lamps and optical devices worth at least $ 1,000 — four cameras aimed two at each of the book’s halves, and a lidar that created a three-dimensional grid on the surface of the pages to correct their curvature. The operator turned the pages manually - not a single machine could do it so quickly and accurately - and made a photo with the help of a foot pedal, as if playing a strange piano.

The effectiveness of the system was provided by special software. Instead of trying to perfectly position each page and flatten it before photographing, which hindered traditional scanning systems, images of curved pages were fed to straightening algorithms that used data from lidars and ingenious mathematics to straighten the text.

At the peak of development, 50 full-time programmers participated in the project. They developed an optical character recognition software that turned a photo into text. They wrote procedures for straightening, color correction and contrast correction to make images easier to process. They developed algorithms for detecting illustrations and diagrams, for extracting page numbers, for processing footnotes, and for ranking books by relevance, according to early research by Brin and Page. “Books are not part of any network,” said Dan Clancy, the project director in his active phase. “Understanding the connections between books is a daunting research task.”

When everyone else on Google was obsessed with “socializing” applications — Google Plus came out in 2011 — Books was viewed by its employees as a task from the “old” era, like the search itself, which responded to the company's mission “to organize information from around the world and make its useful and accessible to all. "

It was the first of the projects that Google compared with the "flight to the moon." Before RoboMobiles and Project Loon - attempts to organize access to the Internet in Africa with the help of balloons - the idea of digitizing books was perceived by the world as an unrealistic dream. Even some googlovtsy considered this venture a waste of time. “At Google, a lot of people asked questions about the feasibility of spending money on such a project, while we were developing Google Book Search,” Clancy told me. “And when Google began to take a closer look at its expenses, then they started saying: 'Wait a minute, is that, does scanning of books take away $ 40- $ 50 million a year from us? And all this will cost us $ 300- $ 400 million? What are you thinking about? ” But Larry and Sergey were very supportive of this project. ”

In August 2010, Google blogpost announced that there are 129,864,880 books in the world, and announced that it was going to scan them all.

Of course, everything turned out a bit wrong. This "flight to the moon" did not reach it by about 100 million books. The result was rather complicated, but it all started simply: Google decided that it was easier to ask for forgiveness than permission, but they did not give him forgiveness. Having learned that the company simply takes millions of books from libraries, scans them, and returns, as if nothing had happened, the authors and publishers filed many lawsuits against the company, accusing it of "massive copyright infringement."

* * *

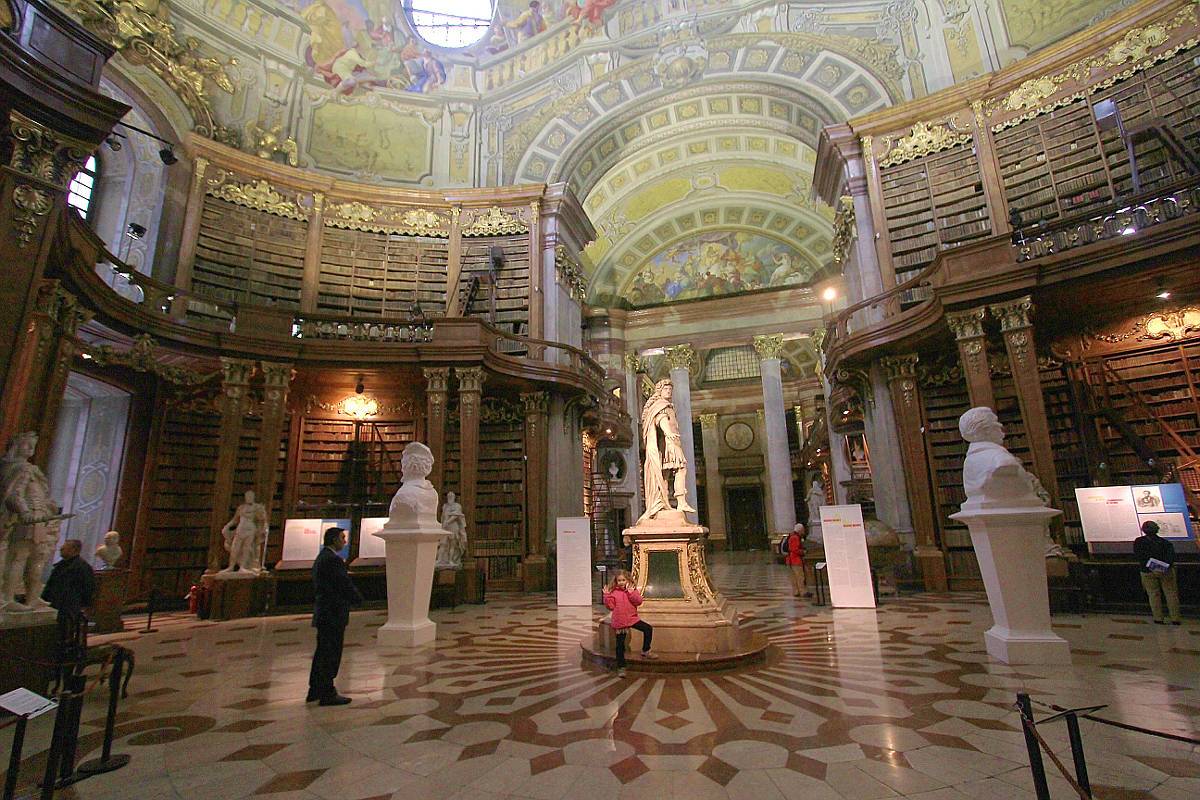

Austrian National Library

When Google started scanning, they weren't going to create a digital library in which they could read books in their entirety; This idea came to them later. Initially, they only wanted to organize a search. For copyrighted books, they showed only “passages” - a few sentences for the context surrounding the search text. They compared their service with a card catalog.

The company believed that the card catalog is protected by the legal notion of “ fair use ”, the same copyright doctrine, which allows scientists to quote a part of other people's work to discuss them. “The border between fair use and everything else is on the transformation of content,” said company lawyer David Drummond. - Yes, when digitizing we make a copy. But the ability to find something according to the term contained in the book is not the same as reading the entire book. This is what Google Books is different from the book itself. ”

Drummond was important to be right. Legal compensation for a “intentional violation” of a copyright may amount to $ 150,000 for each work. The potential liability of the company for the copyright of tens of millions of letters could cost her trillions of dollars. “Google had something to worry about if she put her company at stake in a fair use case,” wrote Pamela Samuelson, a law professor at the University of California at Berkeley in 2011. The rightholders went on the attack.

And they had a reason. The company did not ask anyone for permission, and ruined the library. It seemed wrong: if you want to copy a book, you must have a right to it - that is, this damn copyright. The rightholders felt that if they allowed Google to continue to bulk copy all the books in America, it would create a dangerous precedent that could lead to the disappearance of copyright. The Authors Guild Public Foundation and several book authors personally filed a public lawsuit against Google on behalf of all book copyright holders. Separately from them, a group of publishers filed a lawsuit, but then they combined the lawsuits into one.

The tradition of disrespect for intellectual property rights has long been supported by technology companies. At the beginning of the 20th century, the creators of punched tapes, who controlled the work of mechanical pianos, ignored the rights to musical music , for which music publishers sued them. The same happened with the production of vinyl records and pioneers in the field of commercial radio stations. In the 1960s, cable channels without permission were re-broadcasted on television, for which they were embroiled in an expensive lawsuit. Film studios were suing video recorder manufacturers. Music labels sued the creators of KazaA and Napster.

As Tim Wu wrote in a 2003 article about the history of laws, usually as a result of these battles - what happened to musical punched tapes, records, radio and cable television - the right holders did not crush the new technology. They just made a deal and started making money on it. Often this happens in the form of a “compulsory license”, when, say, a musician is obliged to obtain a license from manufacturers of punched tapes, and for this the manufacturer must pay him a fixed bribe, say, two cents per song, from each tape produced. Musicians get a new source of income, and society can hear their favorite songs on a mechanical piano. “History has shown that time and market forces often provide balance in the search for a balance of interests,” Wu wrote.

But even if everyone wins, each new cycle begins with the fact that right holders are afraid that the new technology will eliminate them. After the appearance of the VCRs, the director of film studios broke loose from the chains. “I think the video recorder will be for American film producers and the public what the Boston strangler for single women has become,” said Congress Congressman Jack Valenti, who was MPAA President at the time. The largest studios were suing Sony, claiming that the company is trying to build a business on intellectual property through its video recorders. But the case of Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc. [ also known as the Betamax affair - approx. trans. ] became famous thanks to a court decision: since the new device could clearly be used for purposes that did not violate the law — for example, to view a home video — the company could not be held accountable for possible copyright violations.

The Sony case made the film industry to accept the existence of video recorders. And soon they began to see new features in this device. “Video recorders have become one of the most profitable inventions - both for filmmakers and for iron producers - since the invention of the film projector,” one of the commentators wrote in 2000.

It took authors and publishers only a couple of years to understand that they have the widest field to find the right compromise. This was especially obvious in the case of books that no one had printed, unlike those that were on the shelves. As soon as you made this distinction, it became possible to see the whole project in a new light. Perhaps, Google does not plunder any property. Perhaps they breathe new life into it. Google Books could have become what video recorders have become for films that have stopped going to the movies.

And if this was the case, then it was not necessary to prohibit Google from scanning books that had ceased to be published. On the contrary, the company could be encouraged not only to show excerpts from the books, but to start selling their digital copies. Out-of-print books were by definition ballast. If Google, having carried out mass digitization, could create a new market for them, it would be a victory for both authors and publishers. “We saw an opportunity to do something unusual for readers and scholars in the country,” said Richard Sarnov, then chairman of the American Publishers Association. “We understood that we could revive a list of books that had ceased to be published and realize their detection and consumption.”

But suppose the authors' guild would win the court: they would hardly have gotten anything from it other than the minimum compensation for damage, and this would not have stopped the company from providing extracts from old books. And in general, these extracts can fuel demand. And let's say, Google will win: the authors and publishers will not get anything, and readers will get only excerpts from the books, and not full access to them.

As a result, the plaintiffs were in a difficult position. They did not want to lose, and did not want to win a lawsuit.

* * *

Bristol Central Library, Britain

The main problem with books that have ceased to be published is that it is not clear who owns them. The author could have signed an agreement with the publisher 40 years ago. The contract postulated that the rights were returned to the author after the book was no longer printed, but he demanded that the author send a written notice to this effect, and certainly did not mention anything about digital rights. And all this was recorded on some paper media that no one else had.

It is estimated that about half of the books published from 1923 to 1963 are already in the public domain — just no one knows exactly which half. Intellectual rights needed to be updated, and often the right holder did not bother with documenting his actions, and even if he documented something, the papers could be lost. And the cost of the procedure of finding out who exactly has the rights to a particular book may be higher than the market value of the book itself. “It’s hard to imagine that people for each piece of work would do this kind of research,” Sarnov told me. “This is not just Sisyphean work, economically it is an impossible task.” In this regard, most of the books that have ceased to be published are closed to the public, if not by copyright, then by inconvenience of access.

The turning point in the case of the authors guild against Google, came when it became clear that the problem can be simply circumvented. The lawsuit was filed on behalf of the public, including everyone who owned the rights to one or more books in the United States. In such a lawsuit, the plaintiffs act on behalf of all interested parties, although anyone who personally wants to abandon it can do it.

So the agreement on this case could theoretically bind almost all authors and publishers of books in the American library. In particular, it was possible to conclude an agreement whereby the owners of rights refused all claims to Google regarding scanning and displaying their books in exchange for a share of book sales.

“If you have this kind of organizational difficulty,” said Jeff Kanerd, a partner at Debevoise & Plimpton, a law firm representing publishers, “you can resolve the issue through a public agreement mechanism that frees you from all past statements and develops a solution to future. Genius was shown by those who saw here the opportunity to approach the problem of books that had ceased to be published and free them from the dusty corners in which they were locked. ”

It was such a tricky move. If the public could be persuaded to agree to the proposed decision and convince the judge to accept it, this step is required by law, since it is necessary to make sure that members of the public act in its interests, then the Gordian knot of ambiguity of rights to old books could be cut. In this way, authors and publishers would simply give Google a green light.

Naturally, they should have received something in return. That was the trick of the plan. A co-licensing plan for old books was attached to the agreement. Individual authors and publishers could withdraw from the agreement at any time. The rest allowed Google to freely display and sell their books, taking into account that 63% of the profits were transferred to a third party, the Registry of Book Rights. The registry was supposed to distribute profits among the owners, who would claim the rights to their books. In ambiguous cases, part of the money would be used to establish the true owner of the rights.

“Book publishing is not the healthiest industry in the world, and the authors themselves do not get anything from the sale of books that have ceased to be published,” Kaner told me. - It’s not that they earn big money on it [through Google Books and the Registry], but they will get at least something. And most authors just want their books to be read. ”

What became known as " amended search agreement in books from Google", has resulted in 165 pages and more than a dozen additions. It took two and a half years to clarify all the details. Sarnoff described the negotiations between authors, publishers, libraries and Google as“ four-dimensional chess. "" Everyone who worked on it, "said he told me, really everything, people from all sides of the business, believed that if they succeed in successfully completing this business, it will become the most important thing of their entire career. ”As a result, Google got $ 125 million, including a one-time payment of $ 45 million to the right holders scanned books - about $ 60 per book - and $ 15.5 million fines in favor of publishers, $ 30 million in favor of the authors and $ 34.5 million for the creation of the Registry.

The agreement described how old books released from oblivion can be shown and sold. According to him, Google will be able to pre-show up to 20% of the book to interest the reader, and offer to buy downloaded copies of books at a price determined by the algorithm specified by the copyright holder. Typically, prices will have to fall in the range of $ 1.99 to $ 29.99. All old books are also organized into a “subscription database for organizations,” which universities can buy and allow students and staff to use it for free. And paragraph §4.8 (a) of the agreement described the creation of an unprecedented “public service” that can be implemented at library terminals throughout the country.

Elaboration of the details took years of litigation and years of discussion, but by 2011 a plan appeared that seemed to work equally well for all interested parties. As Samuelson, a law professor at Berkeley, wrote at the time, “the proposed agreement looked like a triple win: libraries got access to millions of books, Google could recoup their GBS project, and authors with publishers received a new source of income from books that had not brought them nothing".

And, according to her, it was “perhaps the most courageous agreement on a class action suit ever considered.” But, in her opinion, that is why he should have failed.

* * *

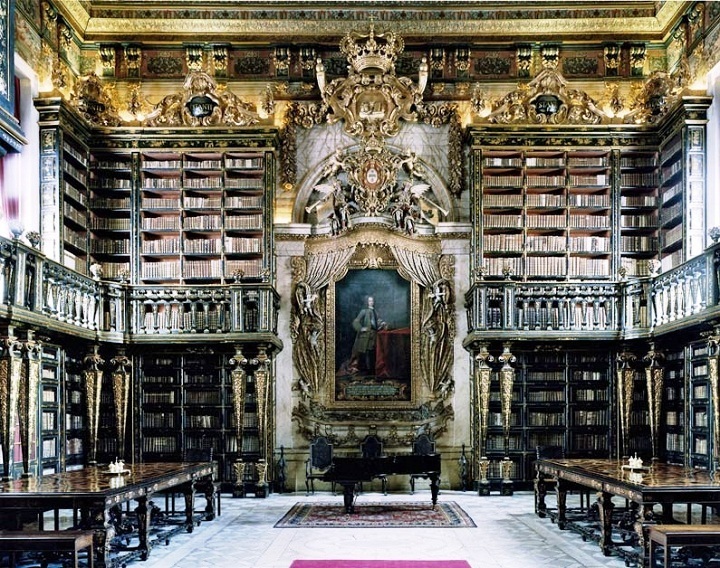

Library of the University of Coimbra in Portugal

Publication of the progress of this case fell into the headlines. This deal was supposed to shake up the whole industry. Authors, publishers, competitors of Google, scientists, librarians, the US government, all interested parties followed every move. When the presiding judge, Denny Chin, sought opinions on the proposed agreement, they fell as if from a cornucopia.

The participants in the discussion, who worked out the provisions of the agreement, expected a kind of resistance from the public, but not such a "parade of freaks" as Sarnov described before him. The objections were very different, but it all started with the fact that the agreement gave Google, and only Google, great power. “Do we want the greatest library in existence to be in the hands of one giant corporation that can charge any fee for access to it?” Asked Robert Darnton, President of the Harvard Library.

At first, Darnton supported the Google book-scanning project, but the deal bothered him. He was afraid that the fate of the GB database would repeat the fate of the academic journal market. At first, the price will be acceptable, but when libraries and universities become dependent on the subscription, the price will rise and grow until it begins to compete with usury prices for subscriptions to scientific journals. For example, in 2011, the annual subscription to the Journal of Comparative Neurology [Journal of Comparative Neurology] could reach $ 25,910.

Although scholars and librarians like Darnton were happy with the possibility of opening access to old books, they decided the deal would be a deal with the devil. Of course, it will help create the greatest of all existing libraries - but at the expense of creating the largest bookstore managed by a powerful monopolist. From their point of view, there should have been a better way to organize access to the books. “Most of the points of the GBS agreement really seemed to work in the public interest, except for the fact that the agreement limited the benefits of this deal to Google,” wrote a law professor from Berkeley, Pamela Samuelson.

Google competitors felt out of work. Microsoft predictably stated that this would lead to an even greater monopolization of Google as the dominant search engine in the world, since only it could search the old books. Using books to respond to user requests, Google will gain an unfair advantage over competitors. Google responded to this by saying that anyone, if they wish, is free to scan all the books and show them in the search results - and that such an act will be a legitimate use of information. Indeed, this year the Second US District Court ruled that scanning books and displaying excerpts from them was in fact their legitimate use.

“There was a hypothesis about the existence of a serious competitive advantage,” Clancy told me. But he noted that this data was never included in any of the main Google projects, since the amount of data on the web exceeds everything that is available in the books. “You don’t need to refer to the book to find out when Woodrow Wilson was born,” he said. The data from the books are useful and interesting for researchers, but "the way opponents present this data in the form of strategic motivation for the project is nonsense."

Amazon was worried that the agreement would allow Google to open a one-of-a-kind bookstore. Everyone else who wanted to sell old books needed to deal with copyrights separately for each book, which is almost impossible, and the agreement gave Google a license for all the books at once.

This objection attracted the attention of the US Department of Justice, in particular its antitrust department, which began to investigate the agreement. The Justice Ministry noted that the agreement gives Google the monopoly rights on all the old books. In order to obtain similar rights to these books, competitors of the company will have to go through the same abnormal process: scan them en masse, go to court and try to come to an agreement. “Even if it were meaningful to believe that such an unusual story would happen again,” wrote the Ministry of Justice, “it can hardly be called good practice to encourage intentional copyright violations and further litigation.”

Google’s protection was that the essence of antitrust law was to protect clients, and, as one of their lawyers said: “From a consumer’s point of view, the only way to get something is much better than not getting it.” There were no old books online; and now there is a way to buy them. How does it hurt users? A source close to the conclusion of the agreement told me: “Every publisher went to the anti-monopoly committee and said: 'Well, wait, because Amazon occupies 80% of the book market. And Google 0 or 1%. The agreement allows someone to compete with Amazon. So you should see it as supportive, not disruptive. ” And from my point of view it was very reasonable. But it was like talking to a wall. And such a reaction is a shame. ”

The antimonopoly committee did not change its position. The persons involved in the agreement did not have a way out: no matter how “non-exclusive” they would make the agreement, it could only be concluded with Google - since it was he who defended the case. In order for the “guild of authors against Google” agreement to appear, someone other than Google, for example, all companies that wanted to sell digital books, had to stretch the legal boundaries of a class action in excess of all rules.

The antimonopoly committee constantly returned to this issue. In their opinion, the agreement was already quite shaky: the original case concerned whether Google could show excerpts from scanned books, and as a result, the agreement went far beyond the scope of the issue under consideration and focused on creating a clever online market that depends on the authors' indefinite refusal. and copyright publishers. And for a long time not published books of these authors and publishers will not be easy to find. “It was an attempt,” wrote the committee, “to use the mechanism of a class action for concluding business agreements with an eye to the future, far beyond the bounds of the trial.”

The objections of the antimonopoly committee put the agreement in a difficult position: focus the contract on Google, and you will be blamed for obstructing competition. Expand it, and you will be accused of abusing the laws of collective actions.

The arguments of the committee were clear, but the fact that the agreement was ambitious did not mean that it was illegal - simply unprecedented. A few years later, another agreement, which also provided for “business agreements with an eye to the future,” and very similar to this, was approved by another district court. The case dealt with the exploitation of the personal data of NFL players who had retired. An agreement was reached, according to which a licensing organization and distributing profits were established. Kanerd, who also participated in that process, says: “What is interesting, not one of the opponents of the agreement has ever raised the question that Judge Chin’s decision was“ beyond the scope of the issue in question. ” And if this agreement was made ten years ago, Kanerd says, it would become “a very important and serious precedent,”opposing arguments of the antimonopoly committee. “This suggests that the law is a very flexible thing,” he said. “Someone should be the first.”

As a result of the intervention of the committee, the agreement came to an end. No one knows exactly why the committee suddenly decided to intervene and did not remain neutral. Dan Clancy, Google’s lead engineer for the project, believes that the committee’s decision was not influenced by his competitors, but by the people who, it would seem, should have supported him — library enthusiasts, scholars and others. . “I don’t know what would happen to the agreement if all these opponents wouldn’t mind so strongly against him,” he told me. “I don’t know if the antimonopoly committee would intervene if people like Bob Darntons or Pam Samuelson wouldn’t be so active.” Without them, it would be just another complaint from Amazon and Microsoft to Google - and this is nothing new. ”

One way or another, the committee had the last word in the case. At the end of the case, Judge Denny Chin announced that the agreement was not “fair, adequate and reasonable”, citing antimonopolists' objections, and noted that to correct the situation, it is necessary either to make the agreement of the right holders to use each work (which would completely devalue it) , or to achieve a similar decision in Congress.

“Although digitizing books and creating a universal digital library would be beneficial for many,” Chin wrote in the decision, “the antimonopoly committee disagrees.”

* * *

Escorial Monastery Library, Spain

At the conclusion of the hearing, during which various people spoke in favor and against the agreement, Judge Chin asked, out of curiosity, how many objections came from authors and publishers who wished to leave this class action? It turned out that there were more than 500, and even more than 6,800.

Reasonable people could disagree with the legality of the agreement. There were good arguments both for and against him, and it was not at all obvious to the observers which side Judge Chin would take. Apparently, the main influence on the outcome of the case was the reaction of the public itself, on whose behalf the lawsuit was filed. “For my more than 22 years of practice in collective litigation, I have never seen the reaction to the agreement so violently, and so many people opposed it,” says Michael Boney, the lead negotiator on the part of the authors. Probably, such a strong reaction attracted the attention of antimonopolists. She unfolded public opinion against the agreement, and could force Judge Chin to look for reasons to stab him. After all, he, after all, decided the question of whether this agreement was fair for the representatives of the collective,from which a lawsuit was filed. The more these representatives refused the agreement, and the more upset they looked, the more he had reasons to believe that the agreement did not represent their interests.

The irony is that many people who opposed this agreement did so in a way that they actually believed what Google was trying to do. One of the main objections of Pamela Samuelson was that Google would be able to sell books, including her books, although she believed that these books should be free for people. And the fact that she herself, like any author who came under the agreement, could sell these books at arbitrarily low prices, did not suit her, since the books, the authors of which could no longer be found, would be sold for money. Looking back, it seems that this is a typical case when “the best turns out to be the enemy of the good”: it would be much better to get any access to books than to leave them inaccessible - even if you had to pay for it by selling “drawn” books.Even in her conclusion that the agreement went beyond the limits of her competence, she herself wrote: "It would be a tragedy not to bring this dream to fruition, especially now that it is so close to it."

Many of those who opposed the agreement believed that a similar result could be achieved without such an unpleasant process as an agreement on a class action. During the hearings, it was constantly believed that the release of the intellectual property of the old books for mass digitization was more likely “under the authority of Congress.” When the agreement was not accepted, people pointed to the proposals of the US Copyright Office regarding the court proceedings, largely inspired by the current process, and the experience of the Scandinavian countries that opened access to old books as evidence that Congress could succeed where it did not work. have an agreement.

And, naturally, after almost ten years, nothing like this happened. “He didn’t have any support,” Kanerd told me about the proposal by the United States Copyright Office, and now it won’t receive any support. "Many of the people who spoke with me in favor of the agreement said that the people who opposed it they didn’t have a practical mind - they didn’t understand how this world works. “They thought that if we couldn’t cope with this lawsuit, then in the future someone else would be able to release all these books, Congress would pass some kind of law, or something else something will happen. And as for this future ... Only the agreement with the guild was rejected, it was all the same to everyone, ”Clancy told me.

Indeed, it seems unlikely that someone will spend their political capital trying to change the rules for licensing books, and even more so for old ones. “This is not an important topic for Congress to start changing the copyright law,” Clancy said. - This topic will not help anyone in the elections. It will not create a bunch of jobs. ” There is nothing surprising in the fact that the lawsuit against Google was the only way to carry out such a reform: only Google had the initiative and the means to implement it. “Speaking simply,” Alan Adler, a book publisher consultant, told me, “a rich private company was going to pay the bill for what everyone wanted.” Google poured resources into the project, not just for scanning books, but also for searching and digitizing old records containing copyright,to negotiate with authors and publishers; the company was going to pay for the creation of the Register of book rights. Years later, the Copyright Office remained in place with its proposal, which, in fact, was very similar, but whose implementation would have to be paid from the budget upon permission of Congress.

I asked Bob Darnton, who ruled the Harvard Library during the Google Books case, and who opposed the agreement if he had any regrets about what came out of it. “So far, I regret only that attempts to outperform Google are so much limited by copyright law,” he said. He worked on another project of digitizing books, limited to books belonging to the public domain. “Do not think about what, I myself am on the side of copyright, but to leave books belonging to the public domain out of reach for more than a hundred years - this means keeping Americans behind the fence of copyright. I think this is crazy. ”

Admont Abbey Library in Austria

The first copyright law in the United States of 1790 was called the "Act on the encouragement to learn." He determined the duration of copyright in fourteen years, with the possibility of their extension for another fourteen years - but only if the author was still alive by the end of the first term. The idea was to make a “pragmatic deal” between the authors and the reading audience. The authors had a limited monopoly on their work, so that they could earn money with it. But their work quickly shifted to the public domain.

The duration of rights in this country was radically increased, mainly to keep up with Europe, where a standard for the duration of copyright has long existed, equal to the author’s life expectancy, plus another 50 years. But the European idea “is based on natural rights , not onpositive rights , ”says Latif Mtima, who studies copyright law at Howard University Law School. “Their thinking comes from France, from Hugo, and all this, you know,“ My work is my child, ”he says,“ and the state has no right to do anything about it. This viewpoint is similar to John Locke’s worldview.". When the world began to shrink, copyright laws began to become similar to each other, so that any country would be at a disadvantage, freeing up intellectual products for their exploitation by others. And then the American idea of using copyright as a tool, according to the constitution “to advance the progress of science and useful arts” and not to protect authors, degraded to such a state that no books published after 1923 are available to us.

“The greatest tragedy is that we have not budged in the matter of“ anyone's ”works. They lie like that, collecting dust, rotting in the physical libraries, with very few exceptions, Mtima said, and no one can use them. So everyone lost, and no one won. ”

After the failure of the agreement, Clancy told me that Google "seemed to have the air blown out of a balloon." Despite the fact that the lawsuit was eventually won, and that the courts declared that the demonstration of excerpts from the books was legitimate, the company closed all its attempts to scan books.

It's strange for me to think that somewhere in Google a database of 25 million books is stored, and nobody can read them. This is similar to the scene at the end of the first Indiana Jones film, where they hide the Ark of the Covenant on some shelf, lost in the chaos of a huge warehouse. She is there. Books are somewhere over there. People tried to build such a library for many years - such an event would mean the creation of the greatest humanitarian artifact of all time. And so we did something to accomplish this task, and we were already going to give it to the world - and as a result, now it’s just 50-60 petabytes of data on the disk that a handful of programmers have access to, since it was they who closed it.

I asked the person who worked on the project, and what is needed for everyone to have access to these books? I was interested to know how difficult it is to open them. What is worth between 25 million volumes between us and the digital public library?

He said that because of this, the person would have been in big trouble, but he would just need to write one database query. Toggle access control bits from “off” to “on”. The team would have worked in a few minutes.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/404059/

All Articles