The aesthetics of noise in analog music

Excerpt from Damon & Naomi's Damon & Naomi , one of the members of the musical duo Damon & Naomi , in which he examines the aesthetics of noise in analog music and what we have lost by going to the digital.

My favorite recordings sound the worst of all since I most often lost them. Each time the needle runs along the plate, it bites a little deeper into the tracks and leaves traces perceived as surface noise. The information on the disc degrades when playing - as if your eyes made this text blur a little after each reading.

')

Analog audio playback is tactile. This is partly a function of friction: the needle jumps in the groove, the film is pulled along the magnetic head. Friction dissipates energy in the form of sound. So, you hear how the music plays from this carrier. Surface noise and film rustling are not defects of analog carriers, but artifacts of their use. Even the best engineering finds, excellent equipment and perfect listening conditions cannot eliminate them. These are the sounds of time, measured by the rotation of a plate or coil - something like the sounds made by an analog clock.

In this sense, analog carriers resemble our bodies. As John Cage noted, we create noise wherever we appear:

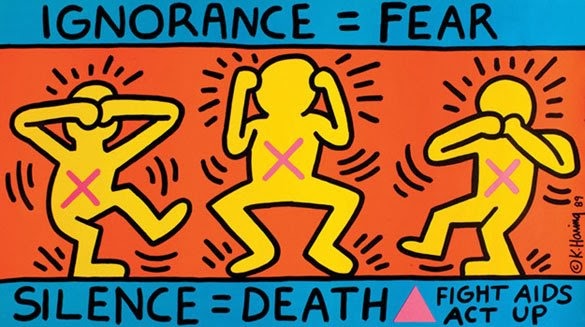

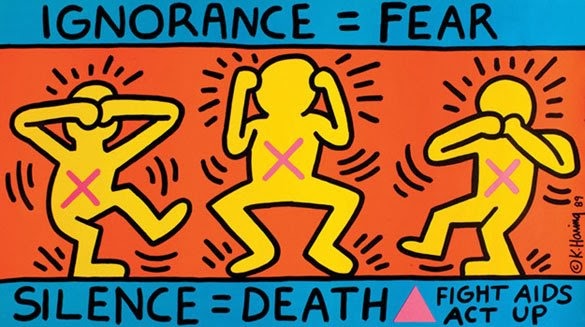

“Silence is death, act,” painfully reminded us of the slogan at the peak of the AIDS epidemic in 1987.

So why seek silence as part of our perception of music?

*

The transition of music to digital media now seems obviously harsh, but in the mid-eighties it seemed so harmless that neither I, nor my friends, musicians, practically noticed it. CDs appeared on the consumer market just like any other items from marketing schemes, with promises of clearer sound, reliability and more free space in the house - all at an appropriately high price. For those of us who enjoyed the records, it all sounded like an advertising speech, seeking to separate bored businessmen from their money. Let them play with a new toy, we thought with friends. Every time when our favorite store of used records received a bunch of LP from the collection of another person, “transforming” his collection by following the new technologies, we congratulated each other on our common sense and did not deny themselves the purchase of new albums at rapidly falling prices. .

Rumors and conspiracy theories about CDs flourished. "It is impossible to combine metal and plastic for a long time," a friend with technical education told me authoritatively. "They will stratify like Oreo cookies." “They are very cheap in production,” said a clerk from a music store, whom we thought was hippie paranoid, because he was a few years older than us. "And if you look directly at the red light in the player, you can go blind." Those who personally heard the sound from the CD - and there were few such people in my environment, because they could not afford to buy the player and the new expensive media - they knowingly said that they sound “cold” and “rude”. The hi-fi sales clerk explained that the dynamic range of the CD exceeded the capabilities of our cheap stereo systems, and they need to be listened to on a new, updated system in order to feel the difference.

So when my then band partner announced that he had bought a CD player to listen to one of our favorite Feelies “Crazy Rhythms” albums, “without scratches,” I disregarded this. And then excitedly asked him to listen too.

Indeed, there were no scratches.

The feeling of the first listening CD I remembered - along with the surface noise of my copy of the record, and, in this case, other noise from a copy of my partner - was like driving a car of the latest model designed for a smooth ride, instead of driving on my rusting Fiat 128 , with a hole in the bottom and problems with a set of high speed. As in the big American car, I no longer felt the surface.

Despite the surrender of my partner and the obvious truthfulness of at least some of the marketing statements, we continued to mock high-tech and sci-fi image: small silver discs made in “clean rooms” and played with the help of light. We wrote snide remarks for our own first CD, which was released only in Europe by a small Benelux record company under the appropriate name “Schemer” [intriguer]:

Although we lost blood at every aspect of our first record, we reacted lightly to the release of the first CD. We invented our comments, typed them on a typewriter, foolishly decided to insert a “bonus track” into the album, which, after long disputes, was refused to LP. We were like Hollywood stars, who fiercely defended their image in the American media, but decided to disgrace themselves in Japan. The CD seemed so far from our musical life that it could easily be meant to go out not just across the ocean, but somewhere on another planet, which we joked about in the notes.

But the joke turned against us. The fact that we were so amused about the CD - the fact that in order to play them you don’t need to touch - it radically distinguished them from the records and ended the musical era in which we grew up. The “digital” nature of the CD corresponded to the fact that they were not touched. And LP on the contrary, we loved to touch. A friend of mine, a record store owner, told me that some collectors even licked them.

If you listen to the analog recording, you can hear all the sounds stored on it: the signal and noise.

*

The intangibility of digital music has a precedent from the early days of recording.

Before the advent of Victrola [the trademark of the phonograph by Victor Talking Machine Company - approx. transl.] and radio, home music meant the presence of musical instruments in the living room. Small guitars are still called "living room guitars", "parlor guitar". The piano remains the largest, most expensive and least portable of all living room instruments. In the US, the economic boom after the Civil War resulted in a jump in piano sales. Until now, these instruments are central to the old US homes, regardless of whether anyone plays them or whether they need them. The PianoAdoption.com website has a list of tools that can be picked up by free pickup. He came up with one tricky porter from Nashua, New Hampshire.

All pianos needed notes. Back in the 1830s, Boston composer and priest Lowell Mason (many Americans still remember his sets of Christian hymns) advocated teaching music in the new system of public schools. By the time Lowell's son, Henry, began producing the Mason & Hamlin piano, “America became the most musically educated nation on earth,” according to the Center for Popular Music. In the gilded century in the United States, sheet music publishers were just as important for intellectual property as piano makers for the industrial economy.

And then, in 1898, a sudden digital invention straightened one with the other: a pianol, or a mechanical piano .

The mechanical piano abandoned musical music in favor of paper perforated ribbons that guided the pneumatic levers. Punched tape is a digital invention before the era of electronics. Like the jacquard loom , it uses holes in the paper that correspond to the binary instructions “on” and “off”. The first device made by this technology, released by Aeolian Company, became so popular that by the 1920s half of the pianos sold in the country supported this technology. Even in Steinway they began to make mechanical pianos.

And while piano makers could make a profit with this technology, the publishers of musical music were deprived of it. The technology punched tape belonged to their manufacturers. By 1902, just four years after entering the mechanical piano market, they had already sold a million punched tapes.

Therefore, publishers did what any software company would do if the producers of iron threatened the product: they sued. Publishers have claimed that digital piano tape violates their copyright by reproducing the music they print, even though it does not directly use their product. It came to the US Supreme Court. And they lost.

By 1908, the Supreme Court decided in favor of a Chicago-based manufacturer of mechanical pianos and punched tapes, refusing a Boston-based music publisher who tried the songs "Little Cotton Dolly" and "Kentucky Babe."

In the case of White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v. Apollo Co. , the court ruled that music is not a “tangible thing”: “In no case can you call musical sounds that reach us through the sense of hearing,” wrote the Supreme Court member William R Day, arguing, therefore, that sounds cannot be subject to copyright.

Of course, punched tapes can be seen, and someone can say that they can be read - but not as music, and it is not a person who can read them. Therefore, Apollo Co. can continue to make punched tapes with impunity with the songs “Little Cotton Dolly” and “Kentucky Babe”, the court ruled, since “these punches are part of the machine”.

The court also noted that the same reasoning can be applied to another new invention: recordings on wax rollers . Judge Day approvingly quotes the words already used by the appellate court:

This decision left the music publishers with nothing. The sound was an intangible thing, and their copyright extended only to physical media. Manufacturers of mechanical pianos and phonographs possessed rights to all the mechanical parts of their devices, and if these parts emitted musical sounds, it was no one except for them.

In Congress, it was accepted without enthusiasm. The following year, they rewrote the copyright law, repealing the decision of the Supreme Court. To save music publishers from Napster-like chaos of mechanical pianos, free of royalty, but without cutting off the wings of the mechanical piano industry, allowing their manufacturers to continue making these devices, the copyright law of 1909 established a system of compulsory mechanical licensing. Mechanical music reproduction (piano tapes, gramophone records) could be made further without the permission of music publishers, if only these publishers were paid statutory deductions for each “mechanical reproduction” created on the basis of their music. By the way, royalties for songwriting are still calculated, and are still called “mechanical royalties” [mechanical royalties].

However, Congress in 1909 refused to change the definition of music, which allowed it to remain in the eyes of the law an intangible thing. Looking back, it seems strange that “musical sounds that reach us through the sense of hearing” - the recordings - remained outside the legal protection of the copyright law until February 15, 1972. Which explains why the music industry of the 20th century focused so much on the labels - tangible, and, therefore, copyrighted objects, which were so important from the point of view of the law that this word became a metonymy for the record companies themselves. Due to the fact that the sound could not be protected by copyright, the symbol of ownership of the object on record labels and envelopes for records was applied only to what was printed on them: logos, drawings, notes to albums.

By 1972, the US law was amended to allow copyright to protect sound recordings, and a new character was even introduced for this, since it was not used for this purpose: Ⓟ, the phonogram [phonogram].

*

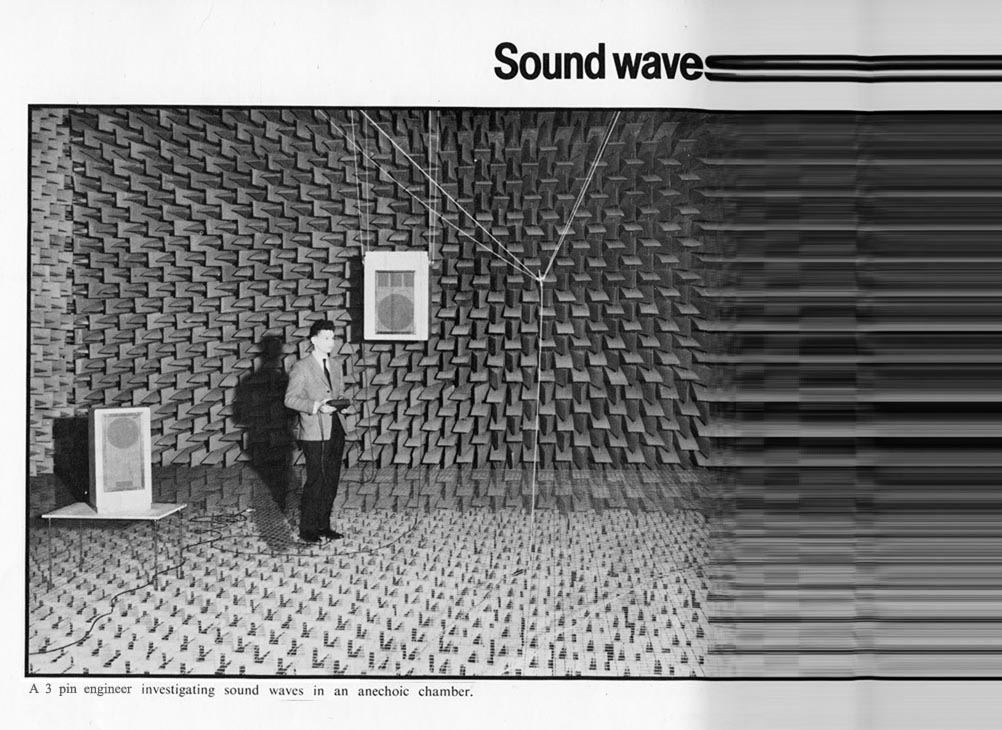

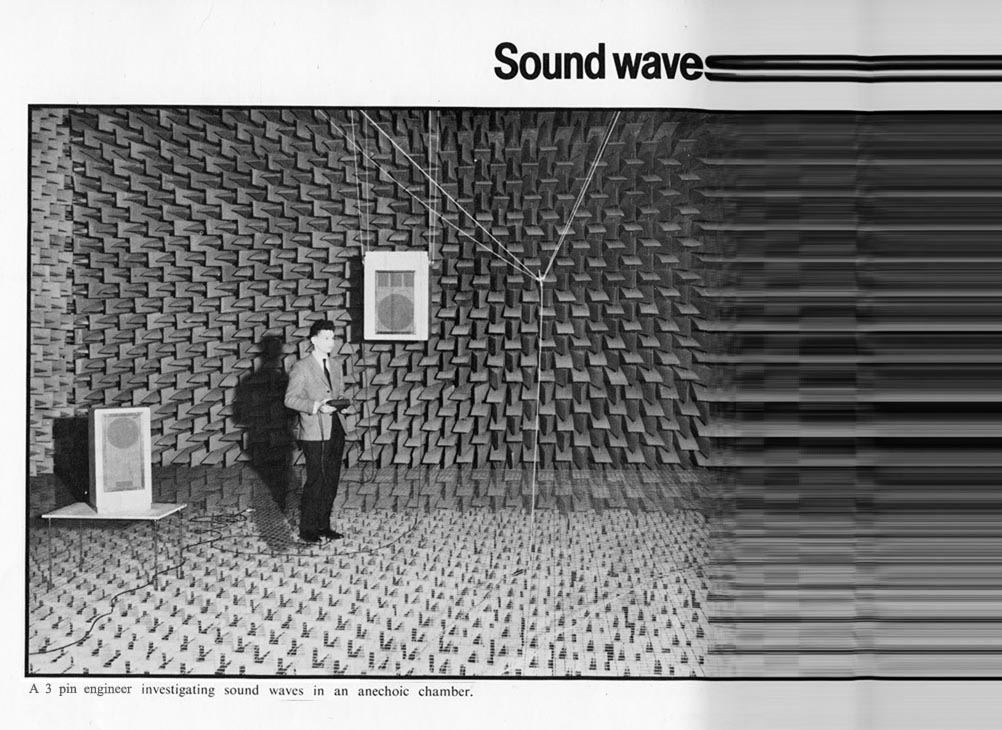

Let us return for a second to the anechoic rooms and John Cage. Cage entered the room to experience silence - what today's audio engineers call digital black, the absence of both signal and noise. But he discovered that his own living body emitted sounds in time: the sounds of the nervous system and blood circulation. “There is no need to fear for the future of music,” Cage concluded — because what is music, if not sounds, distributed in time? Silence is inaccessible to bodily perception, since living bodies occupy not only space (anechoic room) but also time (John Cage in an anechoic room). We can imagine and create the conditions for the disembodied sound, but we will not be able to hear it, since the hearing depends on time. Our ears are as greedy as our fingers, and they clutch for time.

Therefore, the decision of the Supreme Court of 1908 was intuitively wrong. An abstract sound may not be a “tangible thing,” but sounds in time are tangible. The invention of recording sounds allowed people to realize this. “Canned music” - as John Philip Sousa called for the first time recordings - is music preserved for the future. This is the time in the bottle.

As Jonathan Sturn describes in detail in the history of early sound recordings, the invention of canned music is associated with the hobby of embalming that time. The Victorians were obsessed with death, and considered sound recording to be one of the ways to save: “Death and the challenge of the“ voices of the dead ”were met everywhere in records relating to sound recordings in the late XIX and early XX centuries,” wrote Stern. He points out that even Nipper , the famous talisman and model for the HMV logo (His Master's Voice [voice of his master]) is based on the image of a dog listening to a gramophone, which, according to many, stands on the coffin lid.

Nipper reacts to the recording of the voice of his master, since the sound reproduced is palpable in time. Just a little time shifted.

*

The invention of magnetic film in the late 1940s made the time shift more plastic. Wax rollers and gramophone records could save temporary layers, and the film could be cut into pieces of time and rearranged them in places. Glenn Gould called it “amazing splicing,” because it gave him the opportunity to perfect the recorded performance of the compositions, choosing pieces from various attempts. Razor and tape - all that was required to connect different periods of time.

Experimental composers quickly brought this plasticity to the limit, trying to achieve abstraction. “ Specific music, ” as this avant-garde style called this French composer and theorist Pierre Schaeffer , used such mixing of fragments to separate the “sound object” from its source (instrument or sound recording location), and then make it unrecognizable through reduction or other change. . John Cage used splice to rearrange the fragments at random, creating aleatory music . But the hard work needed to cut through the 192-page score of films with different sounds to produce one Williams Mix (1952) with a duration of four and a half minutes convinced Cage to finish the experiments in this area. Each page of the score, describing the cutting of films from two “systems” with eight tracks each, ultimately results in 1 1/3 seconds of playback.

You can assume that a huge number of fragments in the work of the Williams Mix type will only lead to receiving indiscriminate noise. But even in such an extreme job, for which five hundred sounds from different sources were cut and carefully connected, you can hear sounds in time. Our ears catch extremely small fragments, both in sound recordings, and in the real world.

Audio engineers tested the limits of our perceptual abilities, figuring out the smallest sound duration that a person can recognize as a certain note. It turned out that it is equal to 100 ms. In the book " Microsound " Curtis Rhodes writes that our ears can even distinguish sounds of a shorter duration, "individual events ... up to a duration of 1 ms." Such sounds seem to be clicks - but clicks with “amplitude, timbre and spatial location”, so they can be distinguished from each other.

Millisecond - one thousandth of a second. Imagine that the Cage score for Williams Mix stretched across 192,000 pages to describe the same set of sounds with a duration of four and a half minutes. No single analogue could achieve this level of detail.

Or we can say it differently: no analog work can surpass our sense of time.

*

* Reference to a fragment of the cartoon "Yellow Submarine", "The Foothills of the Headlands"

In pop music, manipulations with the film led to a different set of conclusions, more surreal than abstract. Even before the appearance of multi-track tape recorders, musicians and audio engineers realized that they could switch between two tape recorders and overwrite other sounds over one record. The four-track film made this process flexible and efficient enough for the Beatles to record their psychedelic Revolver and Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Having filled all the available space, the Abbey Road recording engineers made a “reduction mix” on one track (on the same tape or on another tape recorder), and continued to add sounds over the top.

The overlapping of the tracks allowed to use the time stored on the film, in a way other than splicing. The splice connects two separate fragments, and the overlap adds many fragments together and creates a super-realistic environment - in which string orchestras and back-playing guitars unite in space and time on one piece of film, unwinding at a speed of 15 "per second.

The listeners of these imaginary sound landscapes were captured by their hyper-reality, and not impossibility. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” is an archetypical example of a song from that era, not only because of the hidden hint of drugs (which John Lennon always denied), but also because it describes the feeling of listening to multi-channel recording. “Imagine that you are sailing on a river in a boat,” she begins, and you could imagine listening to Debussy. But then she adds an unprecedented layer of color: "with orange trees and marmalade clouds." When you get used to this synesthesia and focus on “a girl with kaleidoscopic eyes,” Lennon's voice suddenly moves far away, singing:

Obviously, it was you who could have moved away, becoming very small, while Lennon’s voice could have remained in place. But what happens to the girl we just started to learn?

Boom Boom Boom. Not only the girl disappears, but the entire sound landscape, giving way to the chorus, which appears again in a completely different place. And you also enter this place, just as inexorably, as one moment in time replaces another.

John Lennon pulls us through the changing perspectives of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”, as if leading us through many layers of space and time added by the Beatles to a multi-channel film. Like John Cage's 192-page score for four and a half minutes of music, each of the short pop songs from the Sgt album. Pepper's is based on hundreds of hours of labor. But instead of pressing this time through cutting, as the Cage did, the Beatles again and again layered the films of the same length, until the recording became so busy that it began to resemble the effect of a narcotic drug.

*

Just as there is a physical limit on the number of pieces that can fit on a film of a given length — a limit to which John Cage seemed to fit in his Williams Mix the first time — there is also a limit on the number of layering available for analog media. The film cannot move through the recording apparatus silently, just as we ourselves are not silent in an anechoic room. This means that each layering adds not only more signal, but also more noise, in the form of film hiss. And the hissing layers do not become more narcotic, they become louder.

One of the reasons why great multichannel recordings were made by artists with huge resources - Beatles, Beach Boys - for such recordings you need the best analog equipment that can minimize film hiss for such a large number of runs. Lo-fi artists created similarly dense and psychedelic works. The recording team Elephant 6 began to do their work in high school using a four-channel cassette. But in analog recordings, layering and hissing of a film necessarily go hand in hand. Only capital (or Capitol ) can adequately deal with the noise during the accumulation of layers.

And yet, Sgt. Pepper's and Pet Sounds contain not only a signal, but also noise. These noises are not limited to hissing of the film - they include many auditory artifacts of various places and times superimposed on the film. A good example from Sgt. Pepper's is a distinguishable sound of an air conditioner working in the studio after a bright final chord of the album. Fans used the power of the Internet and crowdsourcing to compile a list of all the noises associated with the signals on the Beach Boys. Here, for example, their list for the song “Here Today” from the album Pet Sounds:

These unintentional noises are inseparable from intentional signals. If Brian Wilson wanted to get rid of them, he would have to re-record the entire track on which they are contained. , . , , .

– . , , . Abbey Road – , , , – «A Day in the Life», .

*

. , : .

Beach Boys, . , . , LP, -, , , , , , .

, – , .

? , .

iTunes , – , -. , , CD , . iTunes , , , .

?

, – , – , . iPod classic Apple 40 000 . , Beatles 237 .

, . , . .

, - . , . – . , , .

? . , , , , . . , , . , .

My favorite recordings sound the worst of all since I most often lost them. Each time the needle runs along the plate, it bites a little deeper into the tracks and leaves traces perceived as surface noise. The information on the disc degrades when playing - as if your eyes made this text blur a little after each reading.

')

Analog audio playback is tactile. This is partly a function of friction: the needle jumps in the groove, the film is pulled along the magnetic head. Friction dissipates energy in the form of sound. So, you hear how the music plays from this carrier. Surface noise and film rustling are not defects of analog carriers, but artifacts of their use. Even the best engineering finds, excellent equipment and perfect listening conditions cannot eliminate them. These are the sounds of time, measured by the rotation of a plate or coil - something like the sounds made by an analog clock.

In this sense, analog carriers resemble our bodies. As John Cage noted, we create noise wherever we appear:

For certain engineering tasks, a room in which complete silence reigns is necessary. Such a room is called anechoic, and its six walls are made of special material. A few years ago, I entered one of these rooms at Harvard University and heard two sounds, one high, one low. When I described them to the chief engineer, he told me that the high sound is the sound of the work of my nervous system, and the low sound of the blood circulation. Sounds will exist with me until my death.

“Silence is death, act,” painfully reminded us of the slogan at the peak of the AIDS epidemic in 1987.

So why seek silence as part of our perception of music?

*

A – A – D

The transition of music to digital media now seems obviously harsh, but in the mid-eighties it seemed so harmless that neither I, nor my friends, musicians, practically noticed it. CDs appeared on the consumer market just like any other items from marketing schemes, with promises of clearer sound, reliability and more free space in the house - all at an appropriately high price. For those of us who enjoyed the records, it all sounded like an advertising speech, seeking to separate bored businessmen from their money. Let them play with a new toy, we thought with friends. Every time when our favorite store of used records received a bunch of LP from the collection of another person, “transforming” his collection by following the new technologies, we congratulated each other on our common sense and did not deny themselves the purchase of new albums at rapidly falling prices. .

Rumors and conspiracy theories about CDs flourished. "It is impossible to combine metal and plastic for a long time," a friend with technical education told me authoritatively. "They will stratify like Oreo cookies." “They are very cheap in production,” said a clerk from a music store, whom we thought was hippie paranoid, because he was a few years older than us. "And if you look directly at the red light in the player, you can go blind." Those who personally heard the sound from the CD - and there were few such people in my environment, because they could not afford to buy the player and the new expensive media - they knowingly said that they sound “cold” and “rude”. The hi-fi sales clerk explained that the dynamic range of the CD exceeded the capabilities of our cheap stereo systems, and they need to be listened to on a new, updated system in order to feel the difference.

So when my then band partner announced that he had bought a CD player to listen to one of our favorite Feelies “Crazy Rhythms” albums, “without scratches,” I disregarded this. And then excitedly asked him to listen too.

Indeed, there were no scratches.

The feeling of the first listening CD I remembered - along with the surface noise of my copy of the record, and, in this case, other noise from a copy of my partner - was like driving a car of the latest model designed for a smooth ride, instead of driving on my rusting Fiat 128 , with a hole in the bottom and problems with a set of high speed. As in the big American car, I no longer felt the surface.

Despite the surrender of my partner and the obvious truthfulness of at least some of the marketing statements, we continued to mock high-tech and sci-fi image: small silver discs made in “clean rooms” and played with the help of light. We wrote snide remarks for our own first CD, which was released only in Europe by a small Benelux record company under the appropriate name “Schemer” [intriguer]:

They just received our signal on Saturn. And the bartender says: yes, the guys sound is awesome.

The sound of today, a few light years away. Flies out of the puzzle and falls into your life. With the help of a laser beam.

Although we lost blood at every aspect of our first record, we reacted lightly to the release of the first CD. We invented our comments, typed them on a typewriter, foolishly decided to insert a “bonus track” into the album, which, after long disputes, was refused to LP. We were like Hollywood stars, who fiercely defended their image in the American media, but decided to disgrace themselves in Japan. The CD seemed so far from our musical life that it could easily be meant to go out not just across the ocean, but somewhere on another planet, which we joked about in the notes.

But the joke turned against us. The fact that we were so amused about the CD - the fact that in order to play them you don’t need to touch - it radically distinguished them from the records and ended the musical era in which we grew up. The “digital” nature of the CD corresponded to the fact that they were not touched. And LP on the contrary, we loved to touch. A friend of mine, a record store owner, told me that some collectors even licked them.

If you listen to the analog recording, you can hear all the sounds stored on it: the signal and noise.

*

Piano

The intangibility of digital music has a precedent from the early days of recording.

Before the advent of Victrola [the trademark of the phonograph by Victor Talking Machine Company - approx. transl.] and radio, home music meant the presence of musical instruments in the living room. Small guitars are still called "living room guitars", "parlor guitar". The piano remains the largest, most expensive and least portable of all living room instruments. In the US, the economic boom after the Civil War resulted in a jump in piano sales. Until now, these instruments are central to the old US homes, regardless of whether anyone plays them or whether they need them. The PianoAdoption.com website has a list of tools that can be picked up by free pickup. He came up with one tricky porter from Nashua, New Hampshire.

All pianos needed notes. Back in the 1830s, Boston composer and priest Lowell Mason (many Americans still remember his sets of Christian hymns) advocated teaching music in the new system of public schools. By the time Lowell's son, Henry, began producing the Mason & Hamlin piano, “America became the most musically educated nation on earth,” according to the Center for Popular Music. In the gilded century in the United States, sheet music publishers were just as important for intellectual property as piano makers for the industrial economy.

And then, in 1898, a sudden digital invention straightened one with the other: a pianol, or a mechanical piano .

The mechanical piano abandoned musical music in favor of paper perforated ribbons that guided the pneumatic levers. Punched tape is a digital invention before the era of electronics. Like the jacquard loom , it uses holes in the paper that correspond to the binary instructions “on” and “off”. The first device made by this technology, released by Aeolian Company, became so popular that by the 1920s half of the pianos sold in the country supported this technology. Even in Steinway they began to make mechanical pianos.

And while piano makers could make a profit with this technology, the publishers of musical music were deprived of it. The technology punched tape belonged to their manufacturers. By 1902, just four years after entering the mechanical piano market, they had already sold a million punched tapes.

Therefore, publishers did what any software company would do if the producers of iron threatened the product: they sued. Publishers have claimed that digital piano tape violates their copyright by reproducing the music they print, even though it does not directly use their product. It came to the US Supreme Court. And they lost.

By 1908, the Supreme Court decided in favor of a Chicago-based manufacturer of mechanical pianos and punched tapes, refusing a Boston-based music publisher who tried the songs "Little Cotton Dolly" and "Kentucky Babe."

In the case of White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v. Apollo Co. , the court ruled that music is not a “tangible thing”: “In no case can you call musical sounds that reach us through the sense of hearing,” wrote the Supreme Court member William R Day, arguing, therefore, that sounds cannot be subject to copyright.

A musical work is an intellectual product that initially exists in the imagination of the composer. For the first time he can play it on the instrument. It cannot be copied until it is turned into a form that other people can see and read.

Of course, punched tapes can be seen, and someone can say that they can be read - but not as music, and it is not a person who can read them. Therefore, Apollo Co. can continue to make punched tapes with impunity with the songs “Little Cotton Dolly” and “Kentucky Babe”, the court ruled, since “these punches are part of the machine”.

The court also noted that the same reasoning can be applied to another new invention: recordings on wax rollers . Judge Day approvingly quotes the words already used by the appellate court:

It cannot be argued that marks on wax cylinders can be seen with the eye or that they can be used in any other way except in the phonograph mechanism. Consequently, they do not make any sense even for the eyes of an expert musician, and they cannot be used at all, with the exception of using them in a machine specially adapted to play the recordings contained on them. These specially prepared wax cylinders cannot replace the copyrighted sheet music sheets and cannot serve a purpose other than the one for which they are intended directly.

This decision left the music publishers with nothing. The sound was an intangible thing, and their copyright extended only to physical media. Manufacturers of mechanical pianos and phonographs possessed rights to all the mechanical parts of their devices, and if these parts emitted musical sounds, it was no one except for them.

In Congress, it was accepted without enthusiasm. The following year, they rewrote the copyright law, repealing the decision of the Supreme Court. To save music publishers from Napster-like chaos of mechanical pianos, free of royalty, but without cutting off the wings of the mechanical piano industry, allowing their manufacturers to continue making these devices, the copyright law of 1909 established a system of compulsory mechanical licensing. Mechanical music reproduction (piano tapes, gramophone records) could be made further without the permission of music publishers, if only these publishers were paid statutory deductions for each “mechanical reproduction” created on the basis of their music. By the way, royalties for songwriting are still calculated, and are still called “mechanical royalties” [mechanical royalties].

However, Congress in 1909 refused to change the definition of music, which allowed it to remain in the eyes of the law an intangible thing. Looking back, it seems strange that “musical sounds that reach us through the sense of hearing” - the recordings - remained outside the legal protection of the copyright law until February 15, 1972. Which explains why the music industry of the 20th century focused so much on the labels - tangible, and, therefore, copyrighted objects, which were so important from the point of view of the law that this word became a metonymy for the record companies themselves. Due to the fact that the sound could not be protected by copyright, the symbol of ownership of the object on record labels and envelopes for records was applied only to what was printed on them: logos, drawings, notes to albums.

By 1972, the US law was amended to allow copyright to protect sound recordings, and a new character was even introduced for this, since it was not used for this purpose: Ⓟ, the phonogram [phonogram].

*

Greedy fingers

Let us return for a second to the anechoic rooms and John Cage. Cage entered the room to experience silence - what today's audio engineers call digital black, the absence of both signal and noise. But he discovered that his own living body emitted sounds in time: the sounds of the nervous system and blood circulation. “There is no need to fear for the future of music,” Cage concluded — because what is music, if not sounds, distributed in time? Silence is inaccessible to bodily perception, since living bodies occupy not only space (anechoic room) but also time (John Cage in an anechoic room). We can imagine and create the conditions for the disembodied sound, but we will not be able to hear it, since the hearing depends on time. Our ears are as greedy as our fingers, and they clutch for time.

Therefore, the decision of the Supreme Court of 1908 was intuitively wrong. An abstract sound may not be a “tangible thing,” but sounds in time are tangible. The invention of recording sounds allowed people to realize this. “Canned music” - as John Philip Sousa called for the first time recordings - is music preserved for the future. This is the time in the bottle.

As Jonathan Sturn describes in detail in the history of early sound recordings, the invention of canned music is associated with the hobby of embalming that time. The Victorians were obsessed with death, and considered sound recording to be one of the ways to save: “Death and the challenge of the“ voices of the dead ”were met everywhere in records relating to sound recordings in the late XIX and early XX centuries,” wrote Stern. He points out that even Nipper , the famous talisman and model for the HMV logo (His Master's Voice [voice of his master]) is based on the image of a dog listening to a gramophone, which, according to many, stands on the coffin lid.

Nipper reacts to the recording of the voice of his master, since the sound reproduced is palpable in time. Just a little time shifted.

*

Amazing splicing

The invention of magnetic film in the late 1940s made the time shift more plastic. Wax rollers and gramophone records could save temporary layers, and the film could be cut into pieces of time and rearranged them in places. Glenn Gould called it “amazing splicing,” because it gave him the opportunity to perfect the recorded performance of the compositions, choosing pieces from various attempts. Razor and tape - all that was required to connect different periods of time.

Experimental composers quickly brought this plasticity to the limit, trying to achieve abstraction. “ Specific music, ” as this avant-garde style called this French composer and theorist Pierre Schaeffer , used such mixing of fragments to separate the “sound object” from its source (instrument or sound recording location), and then make it unrecognizable through reduction or other change. . John Cage used splice to rearrange the fragments at random, creating aleatory music . But the hard work needed to cut through the 192-page score of films with different sounds to produce one Williams Mix (1952) with a duration of four and a half minutes convinced Cage to finish the experiments in this area. Each page of the score, describing the cutting of films from two “systems” with eight tracks each, ultimately results in 1 1/3 seconds of playback.

You can assume that a huge number of fragments in the work of the Williams Mix type will only lead to receiving indiscriminate noise. But even in such an extreme job, for which five hundred sounds from different sources were cut and carefully connected, you can hear sounds in time. Our ears catch extremely small fragments, both in sound recordings, and in the real world.

Audio engineers tested the limits of our perceptual abilities, figuring out the smallest sound duration that a person can recognize as a certain note. It turned out that it is equal to 100 ms. In the book " Microsound " Curtis Rhodes writes that our ears can even distinguish sounds of a shorter duration, "individual events ... up to a duration of 1 ms." Such sounds seem to be clicks - but clicks with “amplitude, timbre and spatial location”, so they can be distinguished from each other.

Millisecond - one thousandth of a second. Imagine that the Cage score for Williams Mix stretched across 192,000 pages to describe the same set of sounds with a duration of four and a half minutes. No single analogue could achieve this level of detail.

Or we can say it differently: no analog work can surpass our sense of time.

*

At the foot of the brain *

* Reference to a fragment of the cartoon "Yellow Submarine", "The Foothills of the Headlands"

In pop music, manipulations with the film led to a different set of conclusions, more surreal than abstract. Even before the appearance of multi-track tape recorders, musicians and audio engineers realized that they could switch between two tape recorders and overwrite other sounds over one record. The four-track film made this process flexible and efficient enough for the Beatles to record their psychedelic Revolver and Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Having filled all the available space, the Abbey Road recording engineers made a “reduction mix” on one track (on the same tape or on another tape recorder), and continued to add sounds over the top.

The overlapping of the tracks allowed to use the time stored on the film, in a way other than splicing. The splice connects two separate fragments, and the overlap adds many fragments together and creates a super-realistic environment - in which string orchestras and back-playing guitars unite in space and time on one piece of film, unwinding at a speed of 15 "per second.

The listeners of these imaginary sound landscapes were captured by their hyper-reality, and not impossibility. “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” is an archetypical example of a song from that era, not only because of the hidden hint of drugs (which John Lennon always denied), but also because it describes the feeling of listening to multi-channel recording. “Imagine that you are sailing on a river in a boat,” she begins, and you could imagine listening to Debussy. But then she adds an unprecedented layer of color: "with orange trees and marmalade clouds." When you get used to this synesthesia and focus on “a girl with kaleidoscopic eyes,” Lennon's voice suddenly moves far away, singing:

Yellow and green cellophane flowers towering above your head.

Obviously, it was you who could have moved away, becoming very small, while Lennon’s voice could have remained in place. But what happens to the girl we just started to learn?

Look at the girl with the sun in her eyes, and now she is gone.

Boom Boom Boom. Not only the girl disappears, but the entire sound landscape, giving way to the chorus, which appears again in a completely different place. And you also enter this place, just as inexorably, as one moment in time replaces another.

John Lennon pulls us through the changing perspectives of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds”, as if leading us through many layers of space and time added by the Beatles to a multi-channel film. Like John Cage's 192-page score for four and a half minutes of music, each of the short pop songs from the Sgt album. Pepper's is based on hundreds of hours of labor. But instead of pressing this time through cutting, as the Cage did, the Beatles again and again layered the films of the same length, until the recording became so busy that it began to resemble the effect of a narcotic drug.

*

Film hissing

Just as there is a physical limit on the number of pieces that can fit on a film of a given length — a limit to which John Cage seemed to fit in his Williams Mix the first time — there is also a limit on the number of layering available for analog media. The film cannot move through the recording apparatus silently, just as we ourselves are not silent in an anechoic room. This means that each layering adds not only more signal, but also more noise, in the form of film hiss. And the hissing layers do not become more narcotic, they become louder.

One of the reasons why great multichannel recordings were made by artists with huge resources - Beatles, Beach Boys - for such recordings you need the best analog equipment that can minimize film hiss for such a large number of runs. Lo-fi artists created similarly dense and psychedelic works. The recording team Elephant 6 began to do their work in high school using a four-channel cassette. But in analog recordings, layering and hissing of a film necessarily go hand in hand. Only capital (or Capitol ) can adequately deal with the noise during the accumulation of layers.

And yet, Sgt. Pepper's and Pet Sounds contain not only a signal, but also noise. These noises are not limited to hissing of the film - they include many auditory artifacts of various places and times superimposed on the film. A good example from Sgt. Pepper's is a distinguishable sound of an air conditioner working in the studio after a bright final chord of the album. Fans used the power of the Internet and crowdsourcing to compile a list of all the noises associated with the signals on the Beach Boys. Here, for example, their list for the song “Here Today” from the album Pet Sounds:

1:15 Mike starts the chorus too early. “She made me feel,” and then someone says something to Mike to stop.

1:27 Something metallic falls at the moment: “She made my heart feel: sad. Sh (sound) e made my days go wrong ... ”In the second verse

1:46 Brian says “everything” as soon as the second chorus ends to rewind the tape and start a new recording.

1:52 Someone is probably saying something about cameras

1:56 Someone answers a man with 1:52

2:03 Brian says “again, please,” probably because he realized that the tape was not stopped after all the sounds

2:20 Conversations

These unintentional noises are inseparable from intentional signals. If Brian Wilson wanted to get rid of them, he would have to re-record the entire track on which they are contained. , . , , .

– . , , . Abbey Road – , , , – «A Day in the Life», .

*

. , : .

Beach Boys, . , . , LP, -, , , , , , .

, – , .

? , .

iTunes , – , -. , , CD , . iTunes , , , .

?

, – , – , . iPod classic Apple 40 000 . , Beatles 237 .

, . , . .

, - . , . – . , , .

? . , , , , . . , , . , .

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403927/

All Articles