Ask Ethan: Is the universe expanding faster than expected?

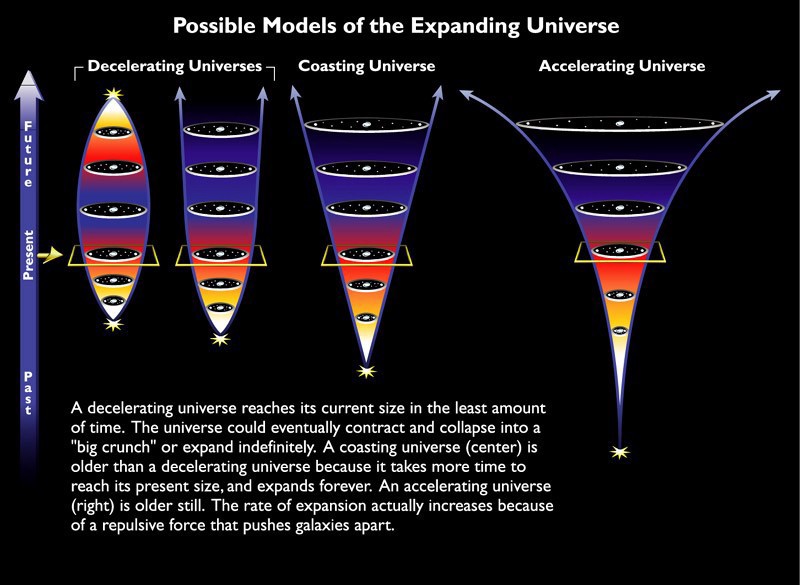

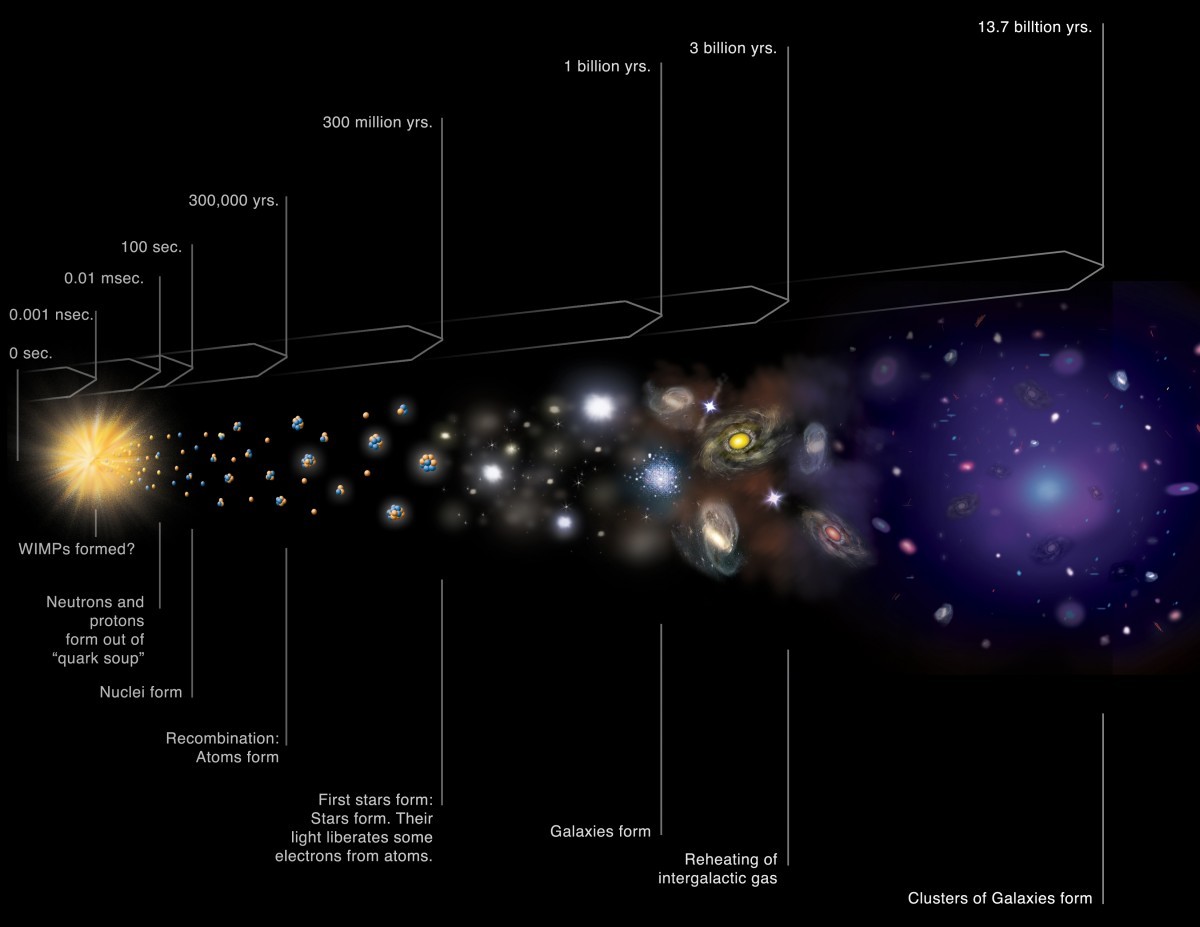

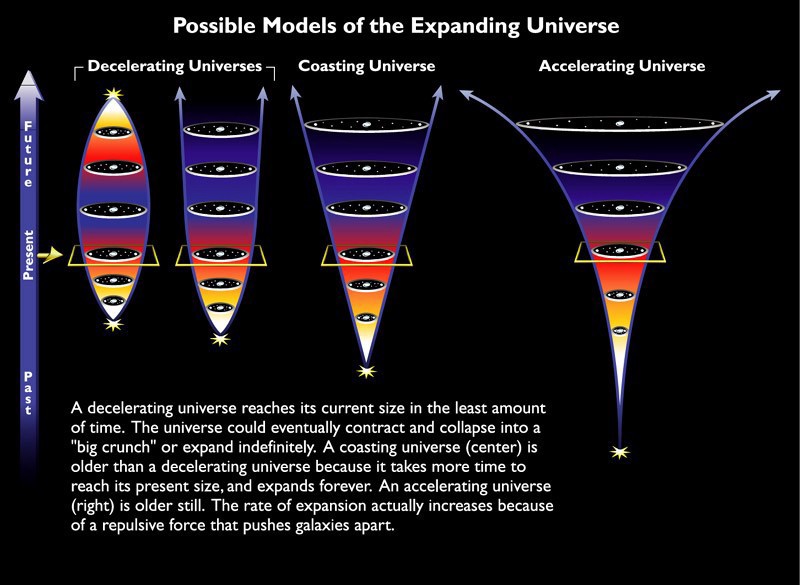

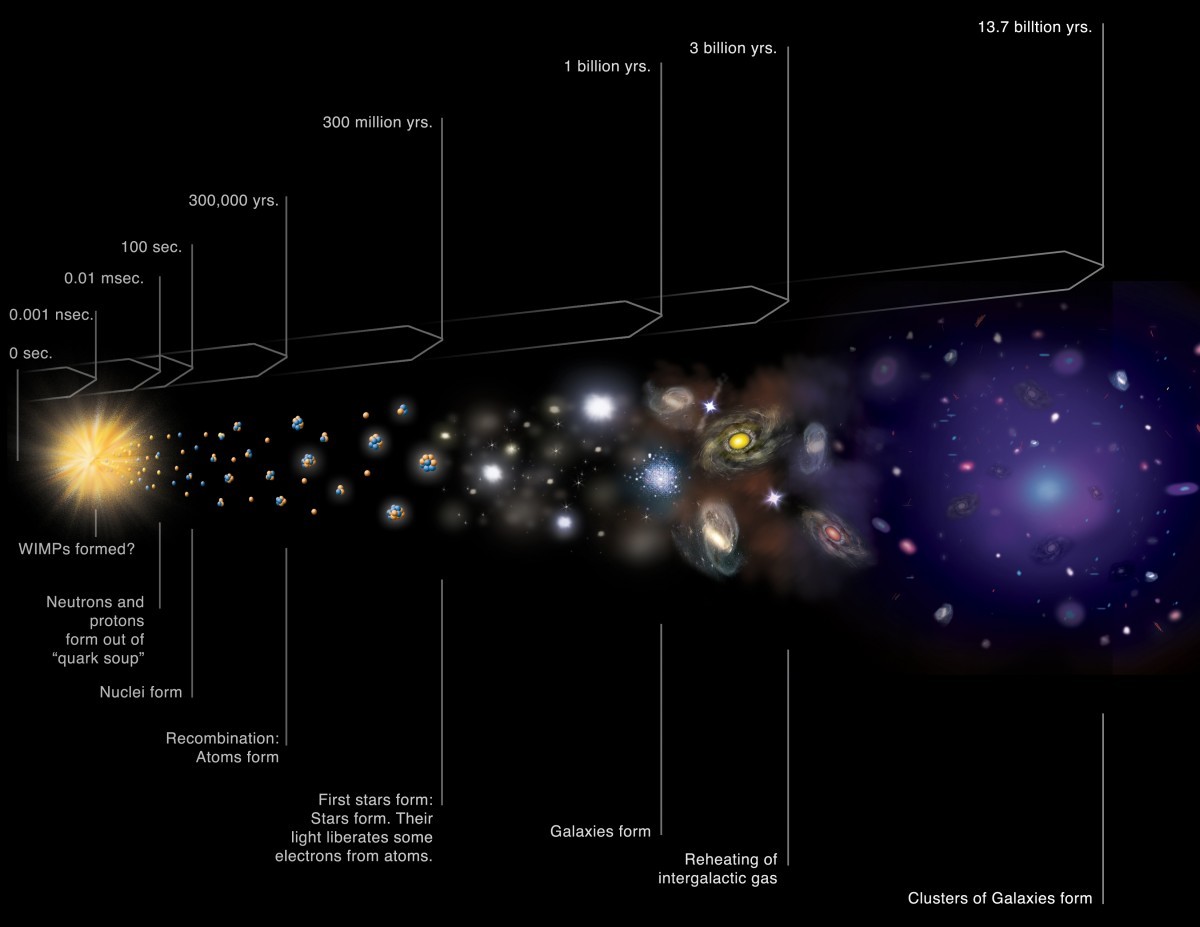

Many of us do not realize that the fate of the Universe, governed by the laws of the General Theory of Relativity, and which began with the Big Bang 13.8 billion years ago, was predetermined from its very birth. The initial conditions are a race between the primary expansion, working to scatter matter and energy to the side, and gravity, working to tighten everything together, slowing down the expansion and, if possible, compressing the Universe in collapse. If we know how the universe is expanding and how it happened in the past, we can calculate what it consists of and what its fate will be - but only if we are able to accurately measure the past.

This week I received a huge number of questions about the news that the universe is expanding faster than expected. The problem is this: if the fate of the universe depends on the rate of expansion, current and past, and we measured it incorrectly, could our conclusions about the universe also be wrong? Can there be no dark energy in it? Could it be that the Universe is not accelerating at all from us? Can the expansion speed slow down and turn into a big compression in the future? To answer these questions, you need to turn to the scientific basis of what is happening.

')

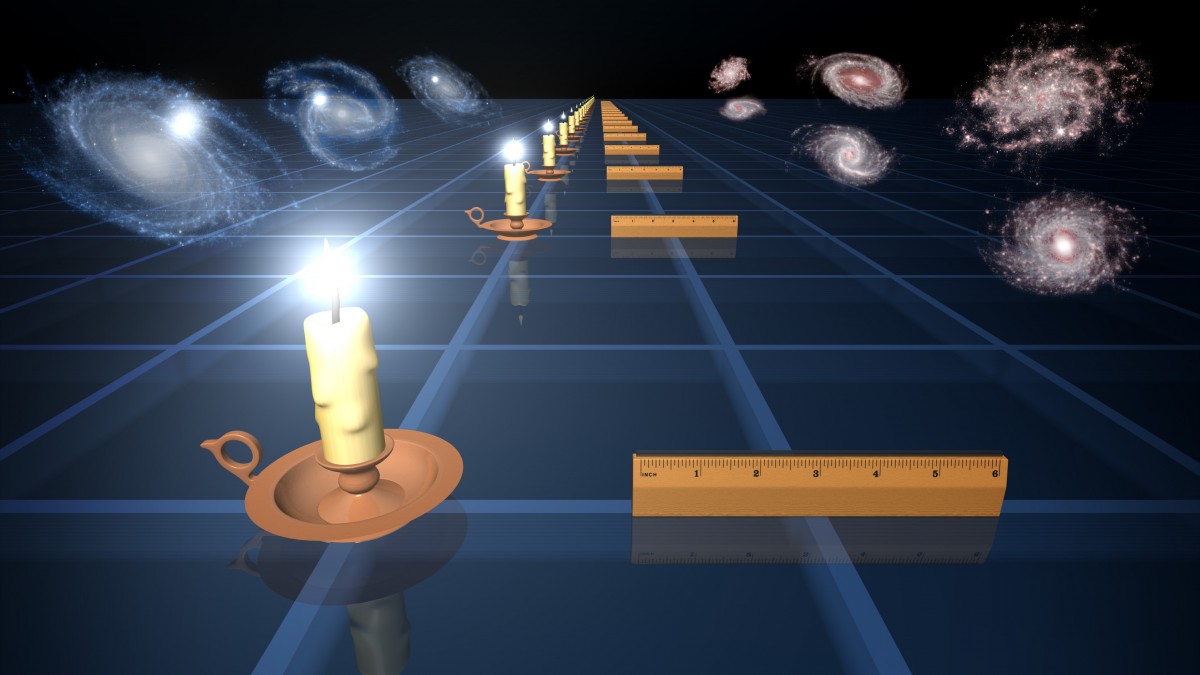

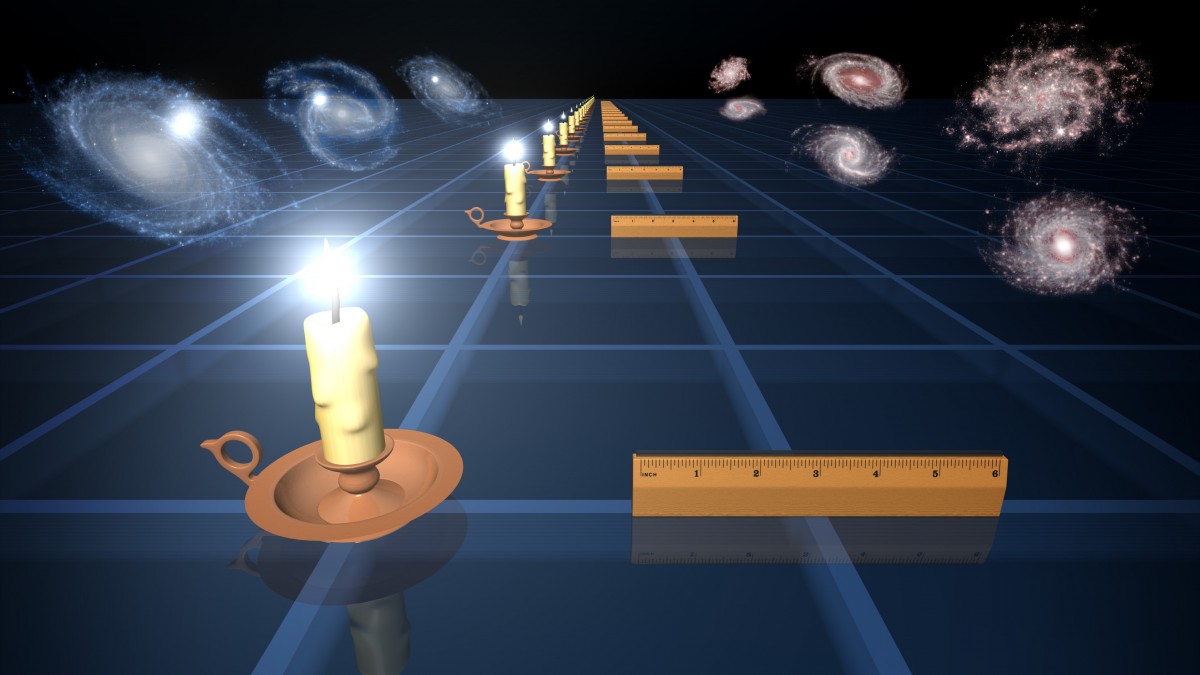

The simplest way to measure the expansion of the Universe is to observe objects well known to us. These are individual stars, spinning galaxies, supernovae, etc. We can measure their apparent brightness and redshift. If we know the real brightness of an object — and for well-studied objects — we know it — and measure its apparent brightness, we can calculate how far it is, just as we can figure out the distance to a 60-watt lamp by measuring its apparent brightness. . Astronomers call such objects “standard candles” because this idea was born long before the light bulbs. As the universe expands, the measurement of redshift and distance allows us to observe how space expands today. And working with more and more distances, we can observe how the rate of expansion has changed with time.

The concept works for many different objects: variable cepheid stars, fluctuations on the surface of spiral galaxies, evolving red giants, rotating spiral galaxies, and type Ia supernovae — the latter can be found at the greatest distances. The combination of these methods was used in the 90s and 2000s to determine the Hubble Universe expansion rate with incredible accuracy: 72 ± 7 km / s / Mpc. It was a breakthrough compared with previous estimates, ranging from 50 to 100. The Hubble Space Telescope, which made these measurements, and was named so because of the intention to measure the Hubble constant!

But since that time, we have further refined the measurements and reduced the errors, which led to a new problem: different measurements give different values of the expansion rate.

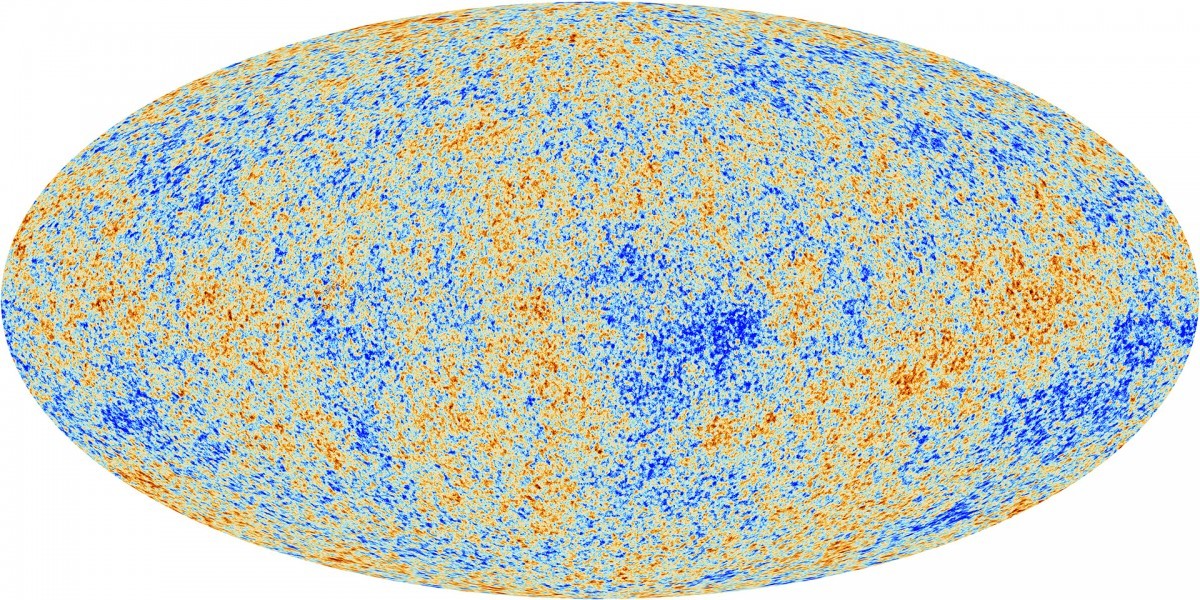

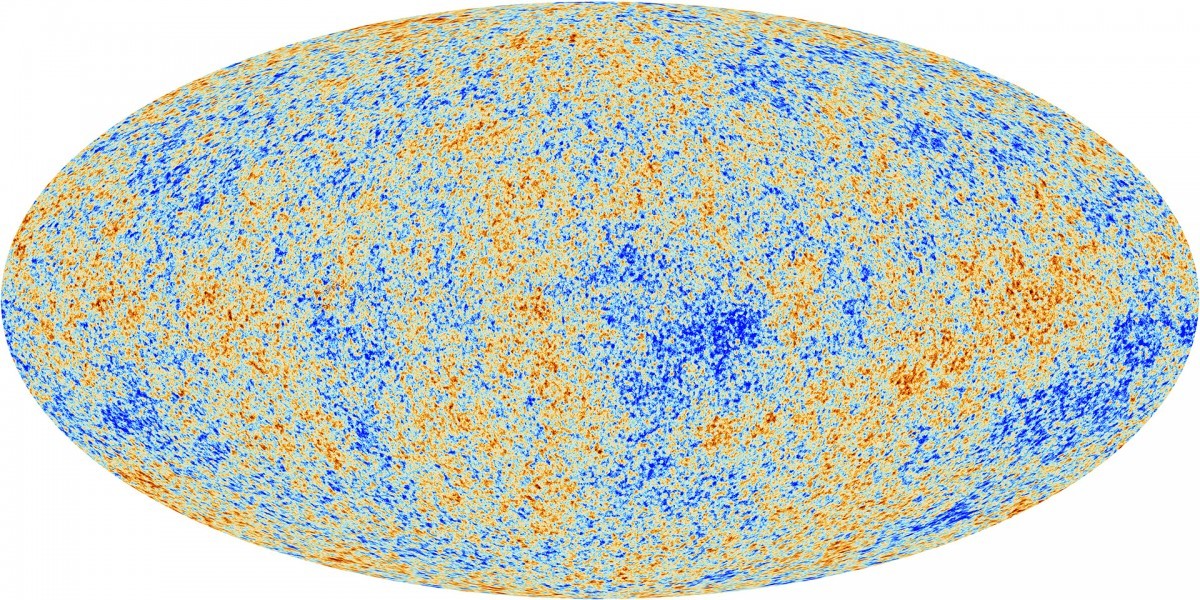

One way to measure the history of the expansion of the Universe is to look at the relic radiation, the residual glow of the Big Bang. Its fluctuations and some general properties allow us to calculate the rate of expansion. The satellite Planck gives us a value of 67 ± 2 km / s / Mpc , which coincides with previous measurements, increasing the accuracy. From clusters of galaxies on the largest scales (baryon acoustic oscillations) measured in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey project and others, we get a value of 68 ± 1 km / s / Mpc . And these two measurements give us values that correspond to both previous measurements and each other. But if we turn to the data on Cepheids and supernovae, when we study Cepheids and Type Ia supernovae in the same galaxy, we will get the same exact value, which, however, does not coincide with the others: 73 ± 2 km / s / Mpc .

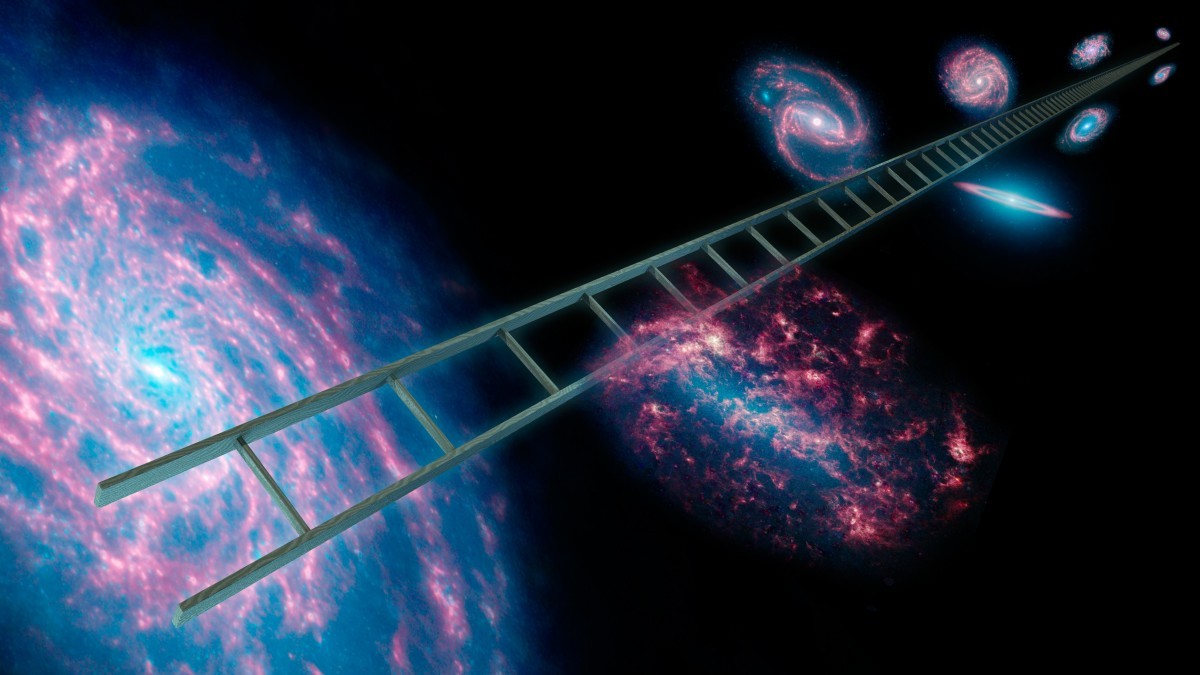

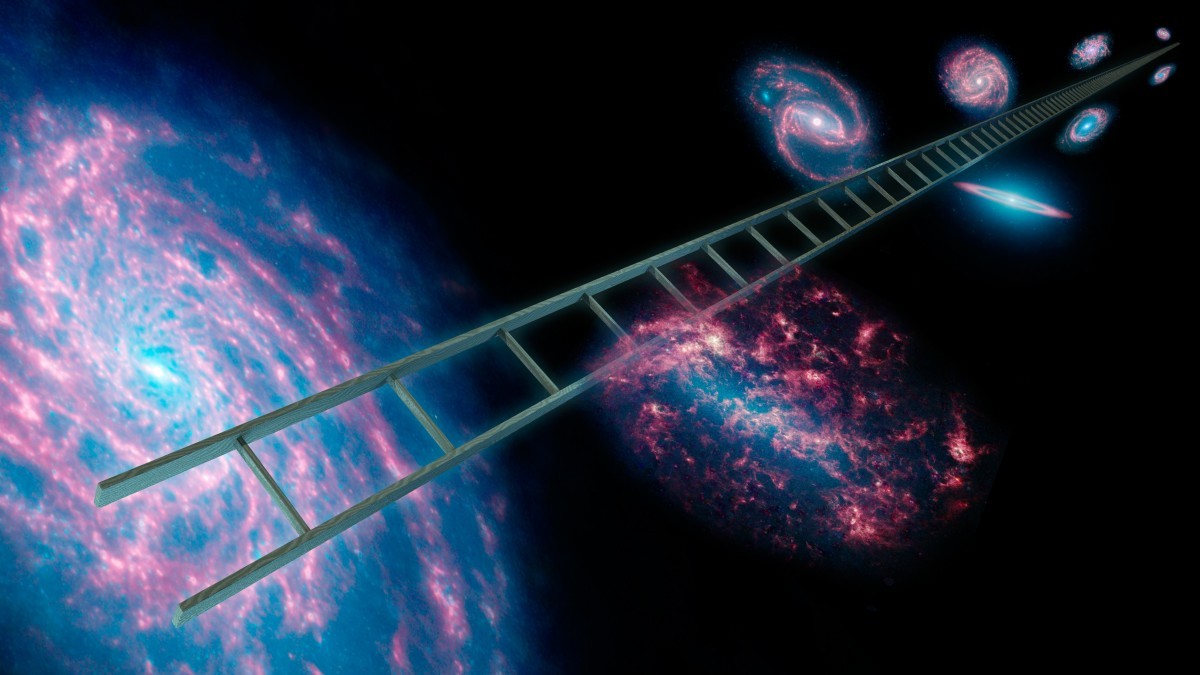

That's because of this and all the fuss goes. Some have begun to offer exotic alternative theories, such as evolving dark energy , while others are already questioning the foundations of cosmology. But it is quite possible, and even likely, that the problem does not exist at all. These errors do not include the systematic errors or uncertainties inherent in the measurement process. The data on Cepheids and supernovae allow us to reconstruct the cosmic distance ladder, in which each step of the expanding Universe is built on a closer previous one. If you make a mistake early on:

• in measuring the parallax of the nearest Cepheids,

• in the standard of these objects,

• in terms of brightness and distance of any of the steps,

• in the estimated real brightness of standard candles,

• about the environment of the detected phenomena,

then this error will spread to all subsequent constructions. Despite the small uncertainty of this distance ladder, it should be noted that there are four independent methods for calibrating the Hubble constant, and each of them produces a different value, from 71.82 to 75.91, and the error of each is approximately equal to 3.

It is hoped that the planned parallax measurements will improve these uncertainties and help to understand the systematic errors that pass through these differences. It is very interesting to talk about unusual topics, but most likely these new signs of uncertainty in the Hubble constant point to the possibility of a better understanding of astrophysical phenomena, thanks to which we obtain these values, and, possibly, as a result, converge on a single value of the expansion rate, one for all techniques. Whether the value will change to 73, whether it will remain around 70 or jump to 67, the result will change our parameters by a few percent, but not our conclusions. Perhaps the universe is not 13.8 billion years old, but 13.5 billion; perhaps it is 65%, and not 70% of dark energy; perhaps in 40 billion years there can be a big gap. But the main picture of the universe will remain unchanged. The key, as always, is to discover the basics of the phenomena and learn what the Universe teaches us.

This week I received a huge number of questions about the news that the universe is expanding faster than expected. The problem is this: if the fate of the universe depends on the rate of expansion, current and past, and we measured it incorrectly, could our conclusions about the universe also be wrong? Can there be no dark energy in it? Could it be that the Universe is not accelerating at all from us? Can the expansion speed slow down and turn into a big compression in the future? To answer these questions, you need to turn to the scientific basis of what is happening.

')

The simplest way to measure the expansion of the Universe is to observe objects well known to us. These are individual stars, spinning galaxies, supernovae, etc. We can measure their apparent brightness and redshift. If we know the real brightness of an object — and for well-studied objects — we know it — and measure its apparent brightness, we can calculate how far it is, just as we can figure out the distance to a 60-watt lamp by measuring its apparent brightness. . Astronomers call such objects “standard candles” because this idea was born long before the light bulbs. As the universe expands, the measurement of redshift and distance allows us to observe how space expands today. And working with more and more distances, we can observe how the rate of expansion has changed with time.

The concept works for many different objects: variable cepheid stars, fluctuations on the surface of spiral galaxies, evolving red giants, rotating spiral galaxies, and type Ia supernovae — the latter can be found at the greatest distances. The combination of these methods was used in the 90s and 2000s to determine the Hubble Universe expansion rate with incredible accuracy: 72 ± 7 km / s / Mpc. It was a breakthrough compared with previous estimates, ranging from 50 to 100. The Hubble Space Telescope, which made these measurements, and was named so because of the intention to measure the Hubble constant!

But since that time, we have further refined the measurements and reduced the errors, which led to a new problem: different measurements give different values of the expansion rate.

One way to measure the history of the expansion of the Universe is to look at the relic radiation, the residual glow of the Big Bang. Its fluctuations and some general properties allow us to calculate the rate of expansion. The satellite Planck gives us a value of 67 ± 2 km / s / Mpc , which coincides with previous measurements, increasing the accuracy. From clusters of galaxies on the largest scales (baryon acoustic oscillations) measured in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey project and others, we get a value of 68 ± 1 km / s / Mpc . And these two measurements give us values that correspond to both previous measurements and each other. But if we turn to the data on Cepheids and supernovae, when we study Cepheids and Type Ia supernovae in the same galaxy, we will get the same exact value, which, however, does not coincide with the others: 73 ± 2 km / s / Mpc .

That's because of this and all the fuss goes. Some have begun to offer exotic alternative theories, such as evolving dark energy , while others are already questioning the foundations of cosmology. But it is quite possible, and even likely, that the problem does not exist at all. These errors do not include the systematic errors or uncertainties inherent in the measurement process. The data on Cepheids and supernovae allow us to reconstruct the cosmic distance ladder, in which each step of the expanding Universe is built on a closer previous one. If you make a mistake early on:

• in measuring the parallax of the nearest Cepheids,

• in the standard of these objects,

• in terms of brightness and distance of any of the steps,

• in the estimated real brightness of standard candles,

• about the environment of the detected phenomena,

then this error will spread to all subsequent constructions. Despite the small uncertainty of this distance ladder, it should be noted that there are four independent methods for calibrating the Hubble constant, and each of them produces a different value, from 71.82 to 75.91, and the error of each is approximately equal to 3.

It is hoped that the planned parallax measurements will improve these uncertainties and help to understand the systematic errors that pass through these differences. It is very interesting to talk about unusual topics, but most likely these new signs of uncertainty in the Hubble constant point to the possibility of a better understanding of astrophysical phenomena, thanks to which we obtain these values, and, possibly, as a result, converge on a single value of the expansion rate, one for all techniques. Whether the value will change to 73, whether it will remain around 70 or jump to 67, the result will change our parameters by a few percent, but not our conclusions. Perhaps the universe is not 13.8 billion years old, but 13.5 billion; perhaps it is 65%, and not 70% of dark energy; perhaps in 40 billion years there can be a big gap. But the main picture of the universe will remain unchanged. The key, as always, is to discover the basics of the phenomena and learn what the Universe teaches us.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403779/

All Articles