How online stores cheat us

Will you pay more for these shoes until seven in the evening? Would the cost of the goods be different for you if you lived in the suburbs? Standard prices and simple discounts give way to more exotic strategies designed to pull out the latest money from the customer.

As Christmas 2015 approached, the cost of pumpkin pie set spices began to behave strangely. It did not take off, as it would recommend a textbook on economics. She did not collapse. She began to oscillate between two quantum states. The cost of packing in ounces on Amazon was either $ 4.49, or $ 8.99, depending on when you looked at it. Almost a year later, on Thanksgiving Day 2016, the price again began to jump between two points - this time between $ 3.36 and $ 4.69.

')

We live in a time of variable prices for tickets and for a taxi ride , independent selection of the price of the Radiohead album and other modern games with prices. But what happened to the spices? Strange computer glitch? More like an intentional glitch. "Most likely, this is a strategy for obtaining data and the right price," Guru Hariharan explained when I outlined this diagram on the board.

The ideal price - the one that will be able to extract the maximum profit from the wallets of consumers - has become the goal of an increasing number of prudent people, many of whom are economists who have dropped out of their studies for the sake of Silicon Valley. The five-year startup Boomerang Commerce, founded by Hariharan, an alumnus of Amazon, is also engaged in it. He says that such price experiments were common practice for finding the perfect price - and repeating the search, because the ideal price changes depending on the day, and even on the hour. Amazon claims that price changes are not attempts to collect data on customers' buying habits, but an attempt to give the buyer the lowest of all prices.

You may be surprised that when you buy ingredients for a seasonal pie, you can participate in a carefully planned sociological experiment. But this is exactly what the habit of comparing prices online has led to. Our ability to find out the price of any product at any time and in any place has given us, consumers, so many opportunities that sellers, in desperate attempts to regain an advantage or at least avoid extinction, are now watching us from that side of the screen. Now they compare buyers.

And for this they have a wealth of opportunities: a huge data loop, trailing behind you, when you add an item to the basket or spend a discount card through the store terminal. The best economists and data processing specialists are able to turn this data into useful pricing strategies. One economist calls this "the opportunity to experiment on a scale unprecedented for the entire history of the economy." In mid-March, Amazon had 59 economist vacancies, and a whole web site dedicated to their employment.

It is no coincidence that old-fashioned pricing schemes - advertising discounts from the regular price, two for the price of one, “daily low prices” - give way to much more exotic strategies.

“I don’t think anyone could have foreseen how complex these algorithms would be,” says Robert Dolan, a Harvard marketing professor. "I here could not." The cost of a can of soda in a vending machine may vary depending on the outside temperature. One study found that the cost of Google recommended headphones may depend on whether your search history gives you a reverent attitude to the budget. For buyers, this means that the price is not the one that is offered to you now, but the one that is offered to you in 20 minutes, or the one that is offered to me or to your neighbor - may become more and more uncertain. “There were a lot of moons back on the subject of the same price,” notes Dolan. Now the simplest question - what is the real price of a set of spices for pumpkin pie - is already subject to a level of uncertainty comparable to Heisenberg.

This raises the question: can the Internet, whose transparency should benefit consumers, engage in the opposite?

If the market is a war between buyers and sellers, as the 19th century French sociologist Gabriel Tarde wrote, then price is a truce. And the policy of fixing a fixed price for a product or service — ingrained in the 1860s — means stopping an eternal hostile state known as trade.

As in any truce, each side donates something. Buyers were forced to agree or disagree with the price announced on the price tag (this innovation is attributed to the pioneer of retail and marketing John Wanamaker ). What the sellers sacrificed - the ability to use varying degrees of buyers' willingness to pay - was perhaps the greater sacrifice, since the amounts that some of the buyers would have agreed to overpay for the goods could no longer be turned into profits. But they still made a deal, from a combination of moral and practical reasons.

Quakers - including New York-based merchant Rowland Macy - never believed in the value of different prices for different people. Wanameyker, a Presbyterian who worked in Quaker Philadelphia, opened his Grand Depot store on the principle of "one price for all, no favoritism." Other traders saw the practical advantages of fixed-price Macy and Wanameker schemes. They slaughtered their new department stores, and teaching hundreds of clerks the art of trading was too expensive. Fixed prices added predictability to accounting, accelerated sales, and served as an abundance of printed advertisements announcing a set price for certain goods.

Companies such as General Motors have come up with a relatively honest way of returning part of lost profits. In the 1920s, GM placed its various car brands in the price hierarchy. “Chevrolet for cattle,” as they wrote in the Fortune store, “Pontiac for the poor but proud, Oldsmobile for reasonable lovers of comfort, Buick for the purposeful, Cadillac for the rich.” This pricing policy, “a car for every wallet and every goal,” as GM called it, was needed to sort consumers, but consumers themselves were sorting. The truce persisted.

Consumers could regain their advantages by collecting discount coupons - their chance to issue a deal that is inaccessible to typical buyers. New supermarket chains in the 1940s made coupons an American way of life. Large sellers understood that behaviorists would later prove this in detail — that consumers needed not only a guarantee of a truce and that they would not be robbed, but also an opportunity to gain an advantage over their neighbors. They liked the deal so much that economists had to distinguish between two types of commodity value: the acquisition value (the buyer’s perceived utility of the new machine) and the transaction value (whether the buyer feels that he lost or won the trade).

The terms of the truce were in the presence of a "list price" and periodic discounts from this price. And such a truce as a whole lasted until the beginning of this century. The ruling retail giant, Walmart, insisted on “daily low prices,” not jumping back and forth.

But in the 1990s, the Internet began to erode the conditions of a long world. Resourceful consumers could go to Best Buy and consider the product they were going to buy somewhere else cheaper - this exercise became known as “showrooming”. In 1999, the digital bookseller from Seattle, Amazon.com, began to expand to become the new Grand Depot.

The era of online retail sales has begun, and hostilities have returned with it.

Looking back, it becomes clear that retailers are slowly mobilizing. While other corporate processes - logistics, sales management - in early 2000, powerful software began to help, capable of making predictions (and even if airlines had variable prices for air tickets), the pricing of retail prices remained more art than science. In particular, it depended on the internal hierarchy of companies. Prices remained the sphere of activity of the second most important figure in the organization: sales directors, whose intuitive knowledge of how and how to sell, was the source of myths that he was not in a hurry to dispel.

But two events weakened the grip of the sales director.

The first is the arrival of data. Thomas Nagle taught economics at the University of Chicago in the 1980s, and recalls that the university then acquired the data of the network of grocery stores Jewel, obtained from the new cash scanners. “Everyone was excited,” says Nagle, now working as the main pricing adviser at Deloitte. “Before that, we relied on flimsy questionnaires like:“ What would you do if you were offered such price options? ”But the real world is not a controlled experiment.

The data from Jewel turned over a lot of what he taught. For example, he said that prices ending in 99 or 98 instead of rounding do not increase sales. Textbooks argued that such prices remained an artifact of those times when store owners wanted to force cashiers to open a cashier to get change, rather than pocket money from sales. “It turned out,” Nagel recalls, “that prices ending in 0.99 do not work with cars or other expensive purchases you are seriously looking at. But in the grocery stores the effect was huge! “

The effect, now known as “the distortion of the left digit”, did not work in laboratory experiments, since the subjects, meeting a limited number of solutions, approached each of the hypothetical purchases as a mathematical problem. But in real life, Nagle admits, "if you were doing this, you would have to spend the whole day at the store." By discarding the numbers to the right of the comma, you can quickly go home and cook dinner.

By the early 2000s, the amount of data collected from retail online stores had become so huge that it began to show gravitational pull. It led to the second event: the arrival of experts in the field of "sad science" [Victorian historian Thomas Carlyle ironically called economics so, in contrast to the term "joyful science", denoting the writing of songs and poems - approx. trans.].

It was a rather strange invasion. For decades, theorists-economists have not paid attention to corporations, and corporations - to theorists. In fact, most theoretical models did not take into account the existence of corporations at all.

But things began to change in 2001, when an economist from Berkeley, Hal Varian , the author of the 1999 approved book Information Rules, met with Eric Schmidt . Varian knew him, but, as he says, did not know that Schmidt became the CEO of a small Google company. Varian agreed to spend academic annual leave on Google, deciding that he would write a book about how people make startups.

At that time, few serious economists from the industry paid attention to such macroeconomic problems as, for example, changes in the demand for consumer durable goods. Varian was immediately invited to take a look at the project, which, as Schmidt told him, “can help us earn a little”: the auction system, which has become Google AdWords. As a result, Varian remained in the company.

Others followed. “EBay was an amusement park for us,” says Steve Tadelis, an economist from Berkeley who worked there in 2011 and now works at Amazon. "That is, pricing, people, behavior, reputation - everything that enthuses economists - plus the chance to experiment on unprecedented scales."

At first, they mainly processed data in search of inspiration. On eBay, Tadelis, for example, used lists of customer clicks to estimate how much money saved visitors an hour of searching for a good price (it turned out that $ 15).

Economists have realized that they can go even further and develop experiments capable of producing data. Carefully monitored experiments not only tried to predict the shape of the demand curve — showing how much goods people would buy, if they increased the price, and helping sellers find the optimal figure that maximizes profits. They tried to build graphs of the curve change by the hour. Online orders are most often made during business hours on weekdays, so sellers are often advised to raise prices in the morning and lower them in the late afternoon.

By the mid-2000s, some economists began to wonder if big data would not help to recognize a personal demand curve for each person — by turning the hypothetical “ideal price discrimination” (the price exactly set at the maximum amount you personally are willing to pay) into a real possibility.

The new world began to take shape, and the initial user experience from online shopping - so simple and so profitable - began to lose its luster.

It is not that it would be unprofitable for consumers to buy at low prices online. They got the benefit. But some deals were not as profitable as they seemed. And some of them began to suspect that they were being ripped off. In 2007, Californian Mark Ekenbardzher decided that he was lucky when he found a set for a gazebo, the catalog price of which was $ 999, sold on Overstock.com at $ 449.99. He bought two, unpacked, and then discovered the remaining price tag on the box, from which it followed that at Walmart, these kits are selling for $ 247. He was furious. He complained to Overstock, and the store offered to refund the cost of the furniture.

But his experience became evidence in the case of consumer advocates against the company Overstock, accused of false advertising. Other clues were internal emails in which employees claimed that the company was known to be in the habit of being extremely overpriced from catalog prices.

In 2014, a Californian judge ruled that Overstock must pay fines of $ 6.8 million. The company filed an appeal. The previous year, there was a wave of similar claims against invented catalog prices, says Bonnie Paten, executive director of TruthinAdvertising.org. In 2016, Amazon began to remove all references to "list prices", and in some cases add a new benchmark: its own previous price for the product.

This may be the last stage of the collapse of the old system with one price. It is replaced by what most resembles high-frequency trading on Wall Street. In the new world, prices are not fixed. They can fluctuate from hour to hour and even from minute to minute - this phenomenon is familiar to everyone who put a product on Amazon and received a notice of a change in its price. The site camelcamelcamel.com monitors Amazon prices for certain products and warns consumers when the price falls below a set bar. The price history for any product — for example, Classic Twister — looks like a typical stock price chart .

And, as in the stock markets, there are quick jumps. In 2011, the book by Peter Lawrence “ How the fly works ” for some time was sold at a price of $ 23,698,655.93 due to the war of price algorithms between two third-party sellers. To understand what happened, it is reasonable to talk to the person who developed the software they use.

Guru Hariharan took the cap off the marker at the boomerang meeting headquarters in Mountain View, California. He talked about what led retailers in such a desperate situation, in which you want to change prices many times a day. On the board, he drew several lines denoting an increasing share of online sales of various goods (books, DVDs, electronics) over time, and then he noted the years in which the main “physical” retailers (Borders, Blockbuster, Circuit City and RadioShack) went bankrupt. At first, these years looked random. But bankruptcies were bored around the band that marked the period when online sales ranged from 20% to 25%. “The point of collapse was in this gap,” said Hariharan, clapping his hands to enhance the effect. “There was a massacre there.”

After this point, traditional retailers with both physical and online stores, felt that they were obliged to compete only in price. Hariharan talked longingly about the days when he could go to RadioShack, and the salesman directed him exactly to the right interconnecting cable. But when retailers got into a zone of collapse, expenses such as staff, training, and user support began to get rid of. And the profit continued to fall - after all, why go to the store, if nobody cares for you anyway? - and the failure became inevitable. RadioShack traveled this route before declaring bankruptcy in 2015.

“It could not have happened,” says Hariharan. Today, he helps retailers deal with this.

We cannot process every price we see. Therefore, we judge the prices of the store on the basis of several well-known products. Sellers have known this for many decades, so they keep the prices of eggs and milk at a minimum, earning on products that are unfamiliar to us.

Working at Amazon, Hariharan, who holds a degree in machine learning, helped invent and patent Amazon Selling Coach, a system that helps third-party vendors optimize their price list.He and his Boomerang team built a massive price-tracking system and have already issued billions of price recommendations for various customers, from Office Depot to GNC and US Auto Parts . But its software does not try to match the lowest available price. This would be a very simple algorithm. It is trying to control the consumer sense of price. It determines the goods that have the greatest value in the eyes of consumers, and maintains their value at the level of competitors, or even lower. And the cost of the rest can be more.

According to him, Amazon has long mastered such tactics. At some point, Boomerang tracked price changes on Samsung's popular TV over the six-month period before Black Friday. Then, this Friday, Amazon dropped the price of a TV from $ 350 to $ 250, dramatically surpassing competitors. Boomerang also found that in October, Amazon inflated the prices of some HDMI cables needed to connect to a TV by 60%, probably knowing, as Hariharan says, that online shoppers are not so jealous about the prices of cheap products.

I wonder how other retailers are starting to adapt. A Boomerang employee showed me a control panel that their customers see. He scrolled through the menu of predefined algorithms to the “bypass competitor by 10%” item set for products that satisfy the following criteria:

If (comp_price>cost) and (promo_flag = false) then set price = comp_price*0.90 That is: if the price of a competitor is higher than the cost price of a thing, and this is not the result of a promotion, then you need to set the price 10% lower than its price. The rule was applied with one click, and on the screen I saw a significant drop in the index of consumer perceived price.

But that is not all. Falling prices will affect the radars of competitors. They will answer the same, or not - depends on how their algorithms interpret the signal. Is this the first shot in the price war? Or is the seller just trying to get rid of stale goods? In practice, it is difficult to say. Therefore, a harmless and temporary price reduction can trigger a price war between cars, which, without proper control, can greatly harm the seller. Boomerang customers are encouraged to set “safety rails” —additional rules that check the operation of other rules — and not to neglect human oversight. Faizal Masood, technology director at Staples, one of the first customers of Boomerang, believes that human intervention is rarely needed. “We want to make it so that software takes decisions, not people,” he says. - Everything is automated. Otherwise, you lose. ”

The complexity of retail pricing has brought at least one Boomerang customer to the field of game theory — a branch of mathematics that was rarely applied to shop windows. Hariharan says with a smile: “She allows you to reason,“ How will the main competitor react to me? And if I know the reaction, what will be my best answer? “And this is already the Nash equation. Yes, that same John Nash , from the “ Mind Games ”, whose brilliant contribution to mathematics has already spread before the price of mops.

What is it all over?

One option: simplicity.

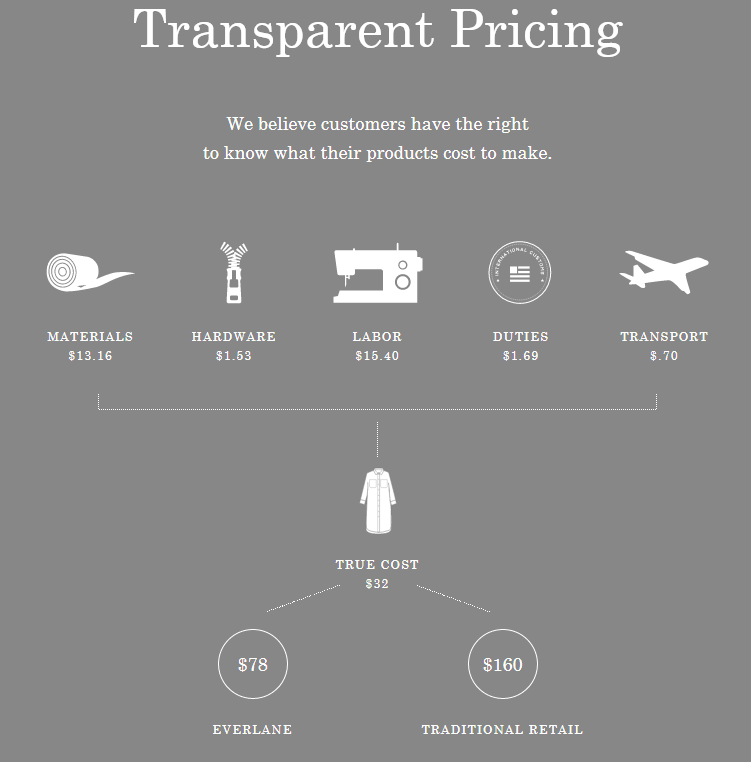

The apparel startup Everlane , for example, puts on the monetization of consumer reactions to even more rare sales tactics. The company announces the price of making each of the products and the profit it has from it.

She recently notified clients that the cost of cashmere from Inner Mongolia has fallen. And she lowered the price of cashmere sweaters by $ 25, since their production began to cost less. “Radical Transparency” - this is what Michael Preisman, the founder and CEO of the company, calls this approach.

Another time, Everlane decided to sell off some models of shoes and clothes, offering users a choice of three options. The lowest price covered the cost of manufacturing and delivery of things. The average covered the costs of sale. The highest brought profit.

If anyone is wondering if the moral dilemma has become an ideal way to set prices, no. 87% of buyers chose the lowest price, says Preisman. 8% chose medium, 5% - high. The point is, Preisman argues, to tell customers how things are going, how employees get paid, and everything else you don’t usually see on a shoe box or sweater label.

"I think the Everlane theory has yet to be proved," Preisman says. Companies in the US "trained buyers to get used to sales. They became the basis of retail sales, and this tendency is very difficult to reverse. This education is hard for buyers to do if you work in the market where people play these games every day. ”

But because of the possibility that consumers do not need transparency, another scenario emerges. They tend to give in to deception and pay more if they think they pay less. That they are deft enough to find the special, best deals designed especially for them. This rejects the principles of the new truce imposed by Everlane. And this will open up opportunities for sellers and economists to get their Holy Grail.

The ideal price should exist only in a theoretical thought experiment. But the idea claims that the seller knows the most reasonable price for each buyer, therefore, by offering him a price a little lower than this, the seller can shake all profits to the last penny.

In the past, vendors used demographic data to calculate the maximum acceptable price. In 2000, some people decided that Amazon was doing just that when customers noticed that they had the same DVDs at different prices. Amazon denied this. This was the result of random testing of prices, as explained by the company's general director Jeff Bezos in a press release. "We have never checked and will not check prices based on consumer demographics."

But demographics are a crude way of personalizing prices, as Benjamin Schiller, an economist at their Brandeis University, asserts in his recent work “First-Class Price Differentiation Using Big Data.” If Netflix only used demographic factors to personalize subscription prices, such as race, family income, and zip code, this model predicted a 0.3% increase in company profits. But if Netflix could use people's browsing history — the percentage of web usage on Tuesdays, the number of visits to RottenTomatoes.com and 5,000 other factors — it could increase profits by 14.6%.

But Netflix doesn't do that. He did not even give Schiller the data he used (he received it from third-party). But Schiller demonstrated that price personalization is a reality.

Do other companies do this? Four researchers from Catalonia tried to answer this question, using computers as fake buyers, imitating the behavior of both rich and thrifty customers, during the week. When these computers went shopping, they were not shown different prices for the same goods. They were shown different products. The average price of headphones, shown as “rich”, was 4 times higher than the price of headphones offered by “economical”. Another experiment showed more direct price discrimination: computers with addresses from Boston were shown prices lower than computers from remote parts of Massachusetts.

In “Determining price and search discrimination on the Internet,” researchers suggested that it would be beneficial for customers to use a system that tracks certain prices (although it is not clear who would have made and supported such a system). In another work, in which Hel Varian from Google took part, it is argued that, with too aggressive price personalization, buyers will behave more strategically, selectively hiding or displaying personal information to get better prices.

Bonnie Patten from TruthinAdvertising.org thinks it's all very difficult. "Discounts are 50% for everything, but with the exception of some products, and because of this, everyone is trying to calculate 20% from 50% in mind." And she already has a full-time job and three children.

“In general, I find it so difficult to determine the real price of a product that when I go shopping with children, I make a decision to buy at the checkout. I ignore prices when choosing, then I get to the ticket office, and if something is too expensive, I refuse it. ”

It seemed to me sanity on the verge of extreme sports. And how does she shop for herself?

“I don’t buy for myself,” Patten said.

“In what sense?” I asked, confused.

“I just gave up. I stopped shopping. ”

At the end of the conversation, I thought about it. Maybe it was because of her work, where she saw too much. Maybe she belonged to the type of "customer-survivors," as she calls them, not experiencing joyful excitement, finding 30-dollar moccasins for sale at $ 8. These thoughts allowed us to reveal an alternative explanation - what Gabriel Tarde called “the madness of doubt”: we can perceive only a limited amount of uncertainty, we are ready to check price fluctuations for goods to a certain point. Somewhere inside us there is a disconnect point for this process, and Patten crossed it.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403459/

All Articles