When intuition brings us: how a single olympiad problem in physics was solved incorrectly for decades

“There are two identical balls at the same temperature. One of them lies on a horizontal surface, the other is suspended from a thread. Both balls reported the same amount of heat. Will the balls be the same after this or not? (Any kind of heat loss can be neglected.) "

Such a task can sometimes be found at physics competitions or social networks . The generally accepted answer is intuitively clear: due to the energy costs of thermal expansion in the presence of gravity, the ball lying on a horizontal surface will be colder than the one hanging on the thread. In a recent article it was shown that this answer is incorrect. In fact, the result will be the opposite: the lying ball will be warmer than the hanging one. Let us see why the traditional method of solving this problem leads to the wrong answer, and why intuition in this case brings us.

The traditional solution and its problem

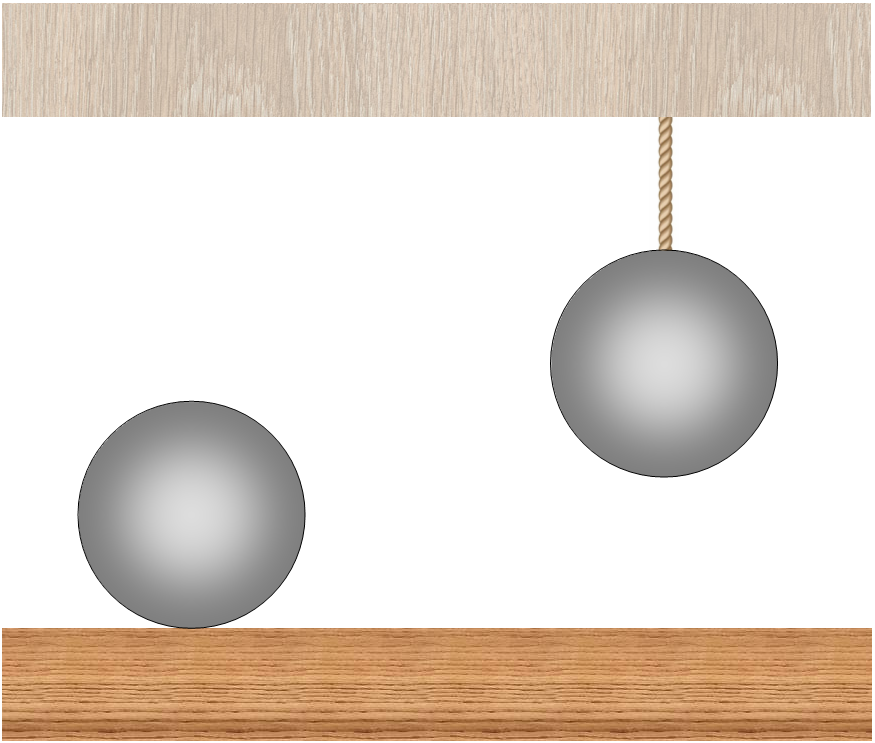

The traditional decision is based on the following chain of reasoning. When the balls are heated, both balls will expand, because of this, the center of mass of the ball lying on a horizontal surface will rise slightly, and the center of mass of the hanging ball will decrease. As a result, the lying ball will heat less, since a part of the heat transferred to it will be spent on its rise, and the hanging ball will heat up more due to the additional work of gravity when lowering it.

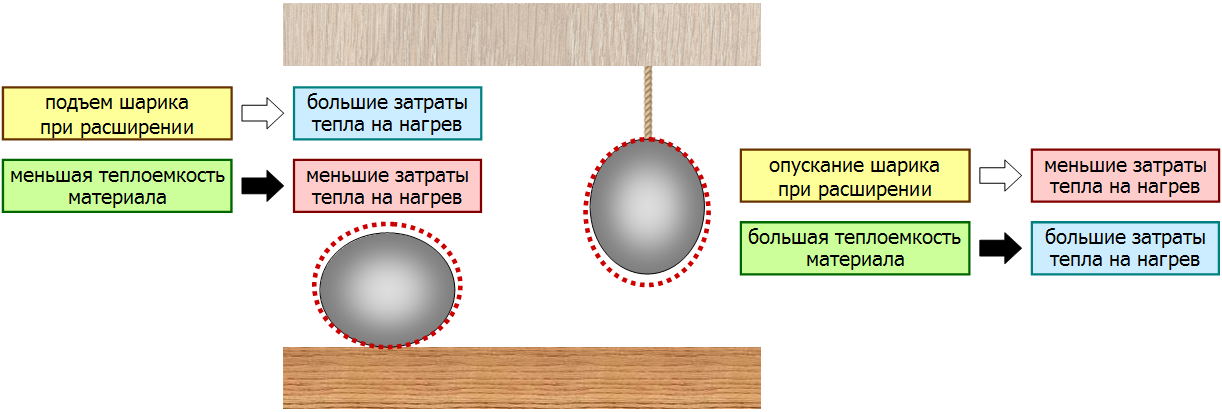

The reasoning used in the traditional solution: due to thermal expansion, the ball lying on the table rises, and the ball hanging on the thread falls.

')

The answer can be expressed by a simple formula for the temperature difference lying (

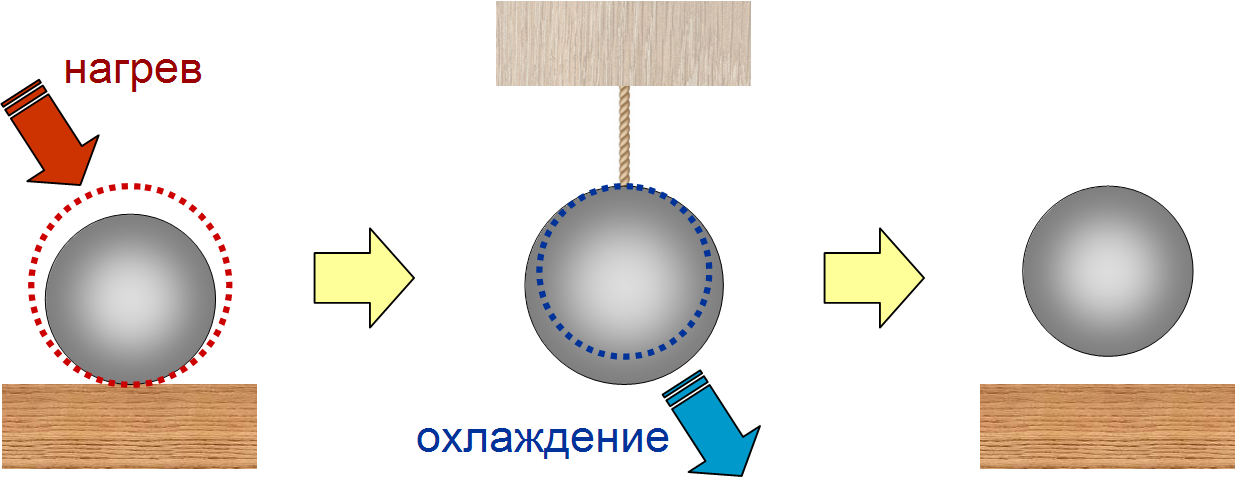

It would seem that everything is logical in this decision. The “first swallow” demonstrating that something is wrong here is a mental attempt to create a heat engine on the basis of a ball.

The machine can work as follows: first, the ball lies on the table, where we heat it, because of which its center of mass rises. Then we fix the ball on the thread hanging from above and carefully remove the table so that the height of the ball does not change. Finally, we cool the ball to its initial temperature, as a result the ball will shrink and its center of mass will rise. The result: a part of the heat that we transmitted to the ball when it was heated turned into a mechanical work to lift it, and this cycle can be repeated endlessly.

The cycle of operation of the heat engine on the basis of the ball: after heating and cooling, the ball has risen, which means that we have converted some of the heat into mechanical work.

The problem here is that, by increasing the radius of the ball, the efficiency of such a machine can be made arbitrarily close to 100%. This contradicts the second law of thermodynamics , according to which the efficiency of a heat engine cannot exceed the efficiency of the Carnot cycle at the same temperatures of the heater and refrigerator.

What is the matter?

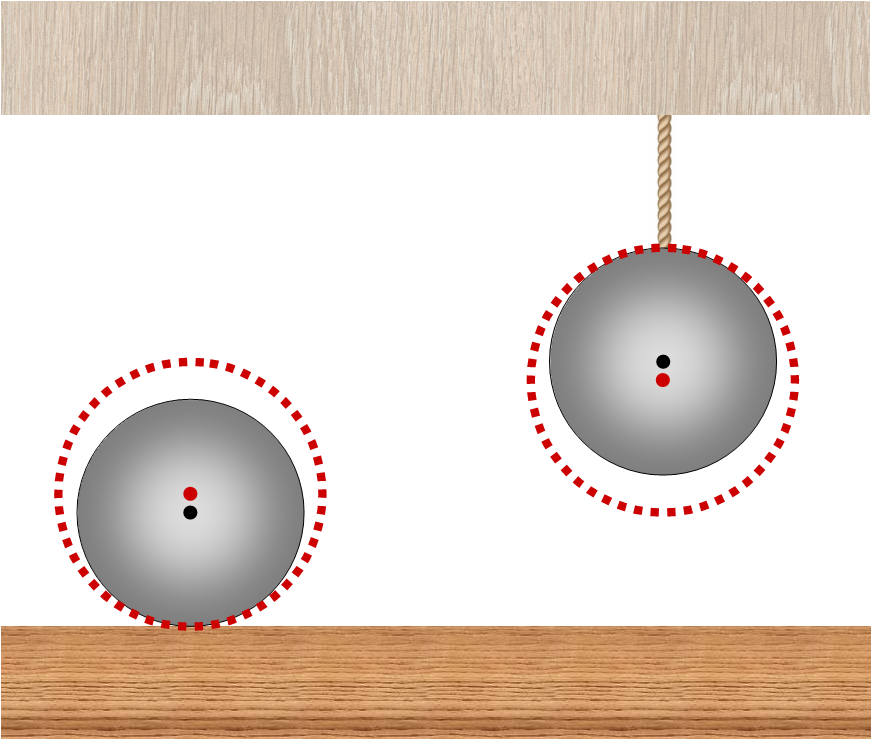

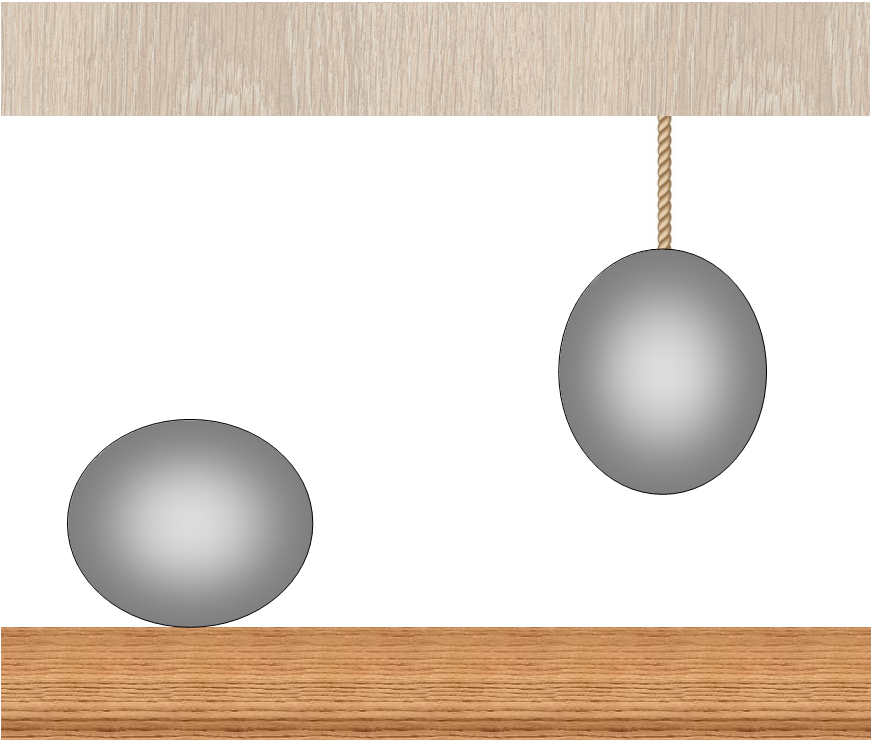

Why is the traditional solution of the problem wrong? Here it is necessary to take into account that the ball lying on the table from the very beginning, before it is heated, will be slightly flattened under the action of gravity, and the hanging ball will be slightly stretched. This will adversely affect the efficiency of the above described heat engine: in the process of hanging, the ball will drop slightly, because of this, the efficiency will decrease and will no longer exceed the efficiency of the Carnot cycle.

The effect of gravity on the balls: the ball lying on the table is flattened, while the ball hanging on the thread is stretched.

How will this appear when considering the original problem? It turns out that compressing or stretching a material changes its heat capacity: in the case of a compressed material, heating by the same temperature will require less heat than in the case of stretched. Consequently:

- When a ball lying on a table is heated, some of the heat will go to its rise due to thermal expansion; but, at the same time, the heating of the material of the ball itself will be easier and will require less heat.

- When the ball is hung on a string, the work of gravity when it is lowered will be added to the heat transferred to it; but, at the same time, the heating of the material of the ball itself will be more laborious and will require more heat.

In the traditional decision, only factors indicated by white arrows are taken into account. Ignoring the factors shown by the black arrows leads to an erroneous answer.

As we can see, in both cases there are factors that work in favor of one answer (the lying ball may turn out to be colder than the hanging one), and in the opposite direction (the lying ball may turn out to be warmer than the hanging one). Which one overpowers?

It would seem that the effect of changing the heat capacity of the material during its compression or stretching, even if it exists, should be very small and can be neglected, as is done with the traditional solution of the problem. However, it is not. This effect is of the same order of smallness as the thermal expansion itself, since both of these effects arise from the anharmonicity of interatomic forces. Taking into account one of these effects in the traditional decision in combination with ignoring the other is inconsistent and leads to an erroneous answer.

The article shows that if the problem is correctly solved, the temperature difference between the balls after the transfer of the same amount of heat to them turns out to be equal:

Compared with the result of the traditional solution, the temperature difference is:

- Opposite sign, as for most materials the value

is positive, so the whole right-hand side of equality is also positive, and

.

- Much smaller in absolute value, since here, instead of a small value, even smaller values appear

and

.

Thus, the two effects discussed above almost completely compensate each other, but the second one (the change in heat capacity under compression or tension) turns out to be slightly stronger than the first (thermal expansion).

Antagonism of interatomic forces

The authors of the article conduct a fairly rigorous review of the problem, but, unfortunately, they do not provide a clear explanation of how exactly the almost complete compensation of the two effects takes place, so I had to figure this out myself.

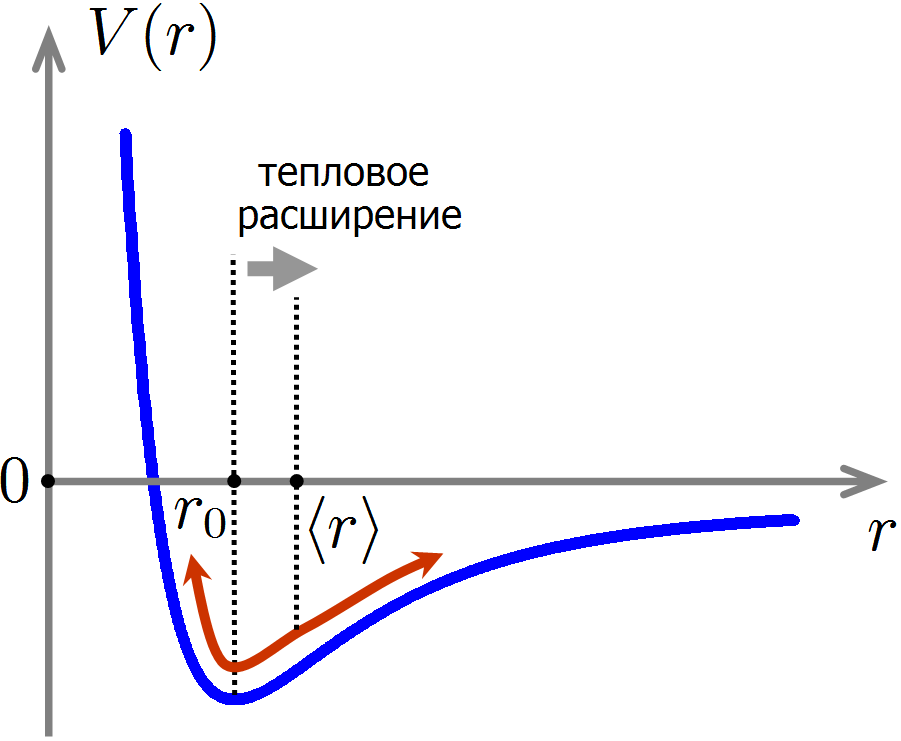

The figure shows a typical dependence of the potential energy of the interaction of atoms on the distance between them. The force acting on atoms is directed in the direction of decreasing potential energy; therefore, atoms strongly repel each other at small distances and weakly attract at large distances. At some distance

Now let's see where the thermal expansion of materials comes from. With chaotic thermal motion, the distance between the atoms is no longer equal to strictly

The cause of thermal expansion of materials: during thermal motion, the average distance between atoms increases due to the anharmonicity of the interatomic interaction forces.

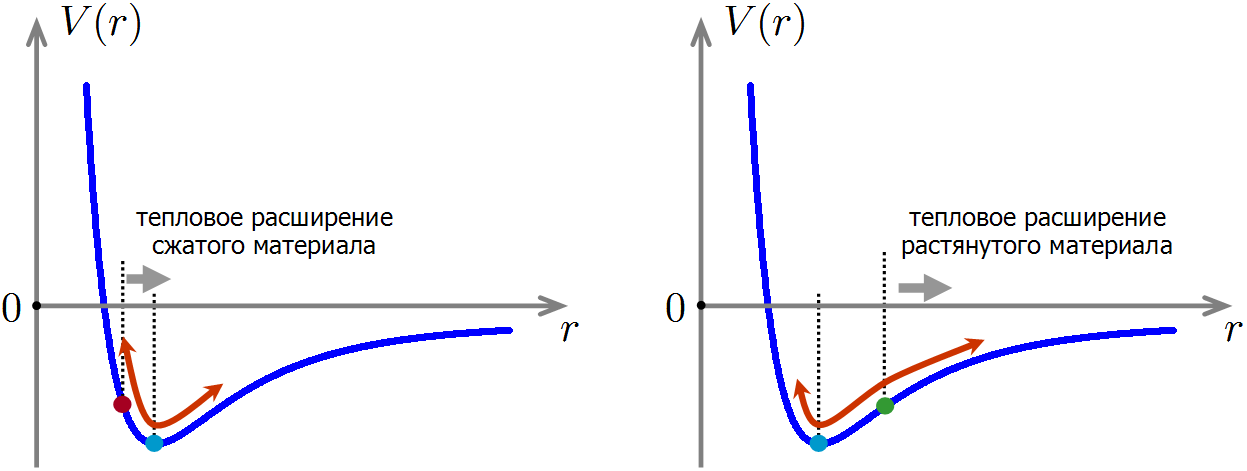

What happens when a material is compressed or stretched, as in the case of flattened or stretched balls? When compressing the material, the external force reduces the average distance between the atoms, and when stretched, it increases.

When compressed, the equilibrium distance between the atoms decreases, and when stretched, it increases.

Now we are ready to understand how the compression and stretching of a material affects its heat capacity. Imagine that we squeezed the material, so that the distance between the atoms during thermal motion now oscillates near the equilibrium position shifted to the left. In this case, the anharmonicity has not gone anywhere, therefore, as before, when heated, the average distance between atoms will increase. But at the same time, we will shift back towards the minimum of potential energy, which means that the energy of the material will further decrease! This explains the decrease in the heat capacity of the material during compression: thermal expansion leads to a slight additional decrease in the energy of interatomic interactions, therefore less energy is required for heating the material.

If the material is stretched, the situation is reversed: with thermal expansion, the interaction energy of atoms will grow faster than in an unstretched material. Therefore, to heat the stretched material at the same temperature, a little more energy is required than without stretching, which means that the heat capacity of the stretched material will be higher.

So, using the example of the Olympiad problem, which has been solved for many decades (and, perhaps, continues to be solved) erroneously, we see that real physics sometimes contradicts our intuition. Therefore, it is so important to carefully use the mathematical apparatus in solving problems, not limited to superficial reasoning.

According to the article :

It is a matter of fact that it is a problem.

Public preprint article: arxiv.org/pdf/1502.01337

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403301/

All Articles