Is matter reasonable: why is the main problem of neuroscience reflected in physics

The nature of consciousness is a unique mystery among all the mysteries of science. Neuroscientists are not just unable to give a fundamental explanation for how it comes from physical states of the brain - we are not even sure that we will ever be able to explain it. Astronomers are interested in what is dark matter, geologists are looking for the origins of life, biologists are trying to understand cancer - and this is all, of course, difficult tasks, but at least we are more or less aware of the direction in which we need to dig, and we There are rough concepts of how their decisions should look. And our own "I", on the other hand, lies outside the limits of traditional scientific methods. Following the philosopher David Chalmers , we call it the " difficult problem of consciousness ."

But, perhaps, consciousness is not one such uniquely complex task. The philosophers of science, Gottfried Leibniz and Immanuel Kant , fought not with such a well-known, but with as complex a task as matter. What is essentially physical matter, apart from the mathematical structures described by physics? And this problem, apparently, is beyond the limits of traditional scientific methods, since we can only observe the effect of matter, but not its essence - “ON” the Universe, but not its “iron”. At first glance, these problems seem completely separate. But if you look closely, it turns out that they are deeply connected.

')

Consciousness is a multifaceted phenomenon, but subjective perception is its most amazing aspect. Our brain does not just collect and process information. It does not just run biochemical processes. He creates a bright series of feelings and sensations, for example, the look of red color, the feeling of hunger, the surprise of philosophy. You are yourself and no one else can recognize this feeling directly.

Our consciousness includes a complex set of sensations, emotions, desires and thoughts. But in principle, the sensations of consciousness can be very simple. An animal that feels pain or an instinctive urge, without even thinking about it, still has consciousness. Our consciousness is also aware of something all the time - it thinks about the objects of the world, abstract ideas, about itself. But he who sleeps and sees an incoherent sleep or hallucinates, will still have consciousness in the sense of having a subjective experience, even though he is not aware of anything concrete.

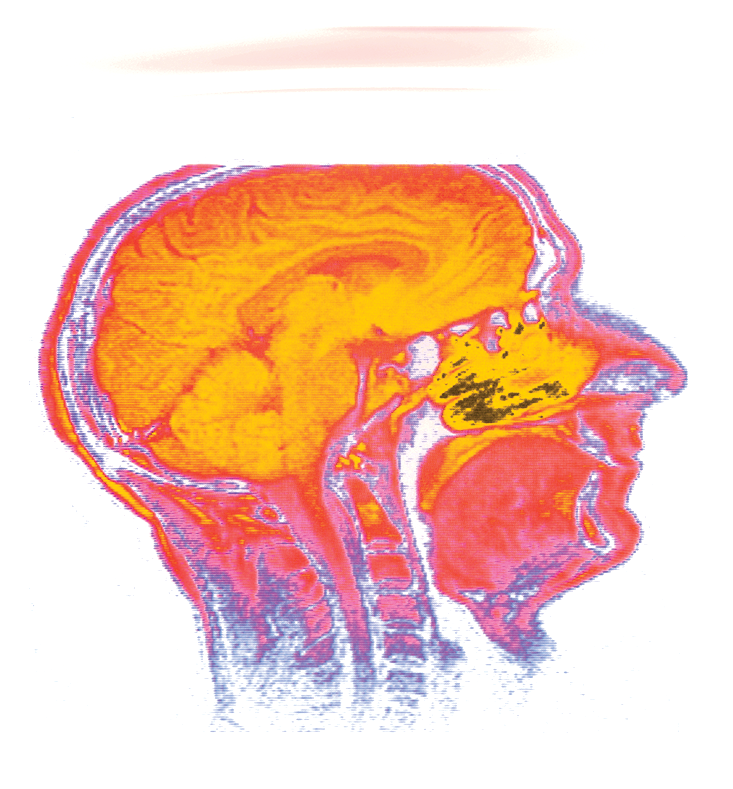

Where does consciousness come from in this most general sense? Modern science gives us reasons to believe that our consciousness grows from the physics and chemistry of the brain, and not from something intangible and transcendental. To obtain a conscious system, we need only physical matter. Collect it in the right way, in the form of a brain, and consciousness will appear. But how and why the consciousness can appear because of the somehow collected matter, which is not conscious from the beginning?

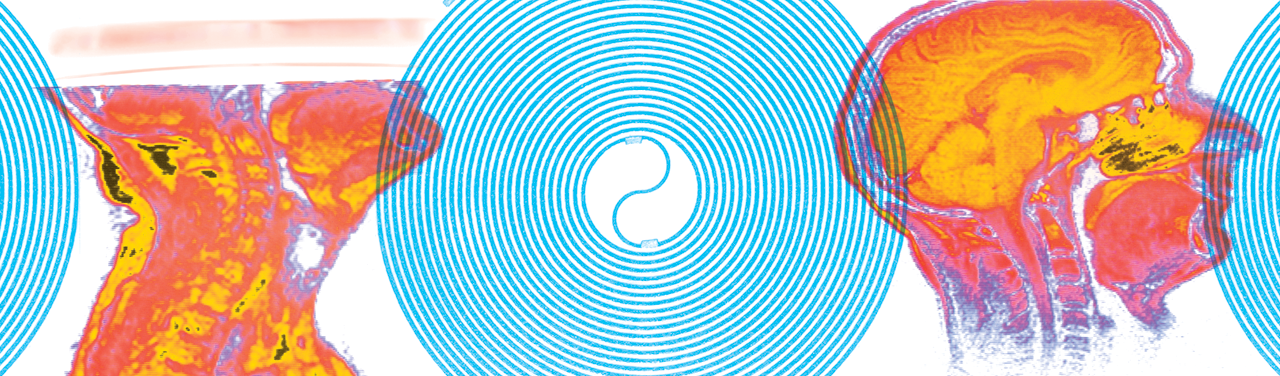

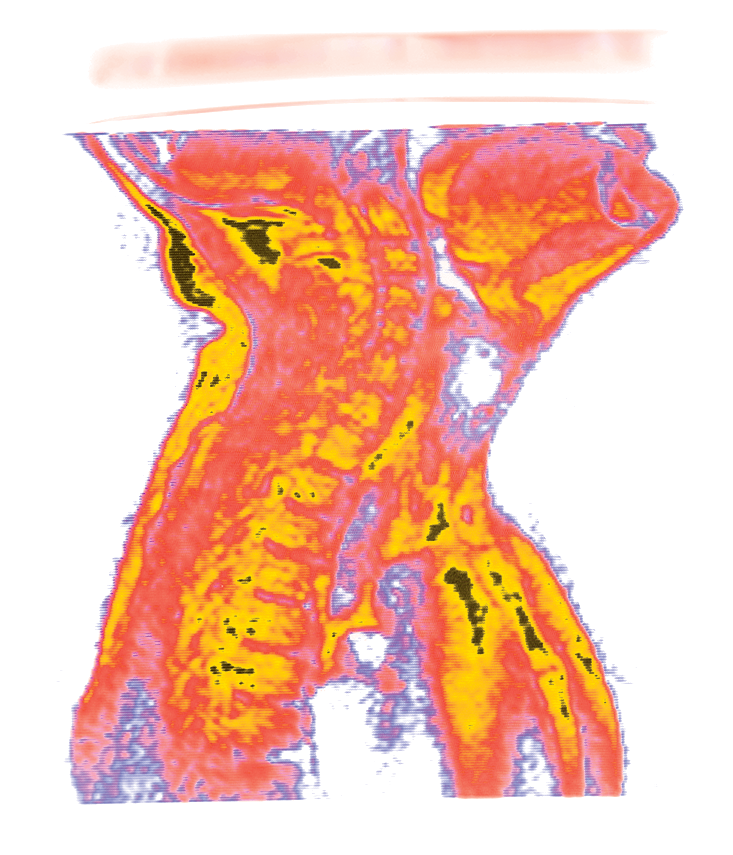

The problem is difficult due to the fact that its solution cannot be described by experiment and observations. Through more and more complex experiments and advanced imaging technologies, neurobiology gives us more and more detailed diagrams of what consciousness feels depending on the physical states of the brain. Neurobiology may be able to tell us someday what all our conscious brain states have in common: for example, they all have high levels of integrated information (as in the " Theory of Integrated Information " from Giulio Tononi ) that they spread messages in brain (as in the Theory of the Global Workspace ) by Bernard Barca , or that they create oscillations at 40 Hz (as suggested by Francis Crick and Christoph Koch ). But all these theories still have a difficult problem. How and why does a system that integrates information, spreads messages or oscillates at a frequency of 40 Hz feels pain or joy? The emergence of consciousness from simple physical complexity seems equally mysterious, no matter what form this complexity takes.

And it seems that the discovery of specific biochemical, and as a result, the physical details underlying these difficulties, will not help us . No matter how accurately we describe the mechanisms underlying, for example, sensations and recognition of tomatoes, we can still ask: why this process is accompanied by a sensation of red, or any other? Why it is impossible to make the physical process go unconscious?

Other natural phenomena, from dark matter to life, albeit mysterious, do not seem so unsolvable. In principle, we can accept that for their understanding it is only necessary to collect more physical details: to build better telescopes and other tools, to develop better experiments, to notice new laws and patterns in the already available data. If we suddenly got knowledge about all the physical details and laws of the Universe, these problems would have to disappear. They would be gone just as the problem of heredity disappeared after the discovery of the physical aspects of DNA. But the difficult problem of consciousness remains, even in the presence of knowledge about all conceivable physical aspects.

In this sense, the deep nature of consciousness supposedly lies beyond scientific possibilities. But at the same time, we believe that physics in principle can tell us all about the nature of physical matter. Physicists tell us that matter is created from particles and fields that have such properties as mass, energy, charge, spin. Physicists could not yet discover all the fundamental properties of matter, but they are approaching this.

But there is reason to believe that matter is something more than physics tells us. Physics, in general, tells us what the fundamental particles do or how they relate to other things, but nothing about what they themselves represent, independently of everything else.

For example, a charge is a property of repelling other particles with the same charge and attracting particles with an opposite charge. In other words, charge is a way of dealing with other particles. Similarly, mass is a property of reacting to applied forces and gravitational attraction of other particles with mass, which can be described as the curvature of space-time or interaction with the Higgs field. There are also other things that particles do and the way they relate to other particles and to space-time.

In general, it seems that all the fundamental physical properties can be described mathematically. Galileo, the father of modern science, once said that the book of nature is written in the language of mathematics. But mathematics is a language with clear limitations. It can only describe abstract structures and connections. For example, we only know numbers as to how they relate to other numbers and other mathematical objects — that is, what they “do”, the rules they follow when adding, multiplying, etc. Similarly, we know the properties of a geometric object, such as a node of a graph, by its relationship with other nodes. In the same way, purely mathematical physics can tell us only about the relations of physical entities and the rules governing their behavior.

You can ask what the physical particles are, regardless of what they do, or how they are related to other things. What are physical entities in themselves, what properties are inherent in them? Some argue that particles are only expressed through their relationships with each other, but intuition rebels against such statements. Relationship requires the existence of two things that have a relationship with each other. Otherwise, this relationship is empty - a play without actors, a castle from the air. In other words, the physical structure must be realized or made of some substance or substance, which in itself is not an empty structure. Otherwise there will be no difference between the physical and mathematical structure, between the tangible universe and the abstraction. But what is this substance that realizes the physical structure, and what are the internal, non-structural properties that describe it? This problem is a close relative of Kant's classic problem concerning the thing-in-itself . The philosopher Galen Strawson calls it the "difficult problem of matter."

There is irony here, since we usually imagine physics as a science describing the "iron" of the Universe - real, concrete things. But in fact, physical matter (at least those aspects of it that physics tells us about) is more like software: a logical and mathematical structure. According to the difficult problem of matter, this software requires iron to work. Physicists ingeniously conducted reverse engineering of algorithms — or source code — of the Universe, but excluded a concrete implementation.

The difficult problem of matter is different from other problems of the interpretation of physics. Modern physics gives us riddles such as: how can matter simultaneously look like a particle and a wave? What is the collapse of the quantum wave function? What is more fundamental, continuous fields or single particles? But all these are questions of how to properly comprehend the structure of reality. A difficult matter problem would have appeared even if we had all the answers about the structure. Regardless of which structures we are talking about, from the strangest and most unusual to quite intuitive, the question will arise: how are they implemented not from a purely structural point of view?

Such a problem appears even in Newtonian physics, which describes the structure of reality at a simple intuitive level. Roughly speaking, Newtonian physics says that matter consists of solid particles interacting either through collision or through gravitational attraction. But what is the inner nature of the substance behaving so simply and intuitively? What is the hardware on which the software of Newton's equations is implemented? Someone may decide that the answer is simple: it is implemented by means of solid particles. But hardness is a behavior that comes from particles that resist the penetration of other particles and partially overlap each other — that is, in fact, another relationship with other particles in space. The difficult problem of matter arises with any structural description of reality, regardless of its quality and intuition.

Just as the difficult problem of consciousness, the difficult problem of matter cannot be solved through experiments and observations, or through the collection of additional physical details. They will simply show us even more structures - at least as long as physics remains a discipline devoted to the description of reality through mathematics.

Can the difficult problem of consciousness and the difficult problem of matter be related? In physics, there is already a tradition of combining problems of physics and problems of consciousness, for example, in quantum theories of consciousness. Such theories are often belittled because of their false conclusions that if quantum physics and consciousness are mysterious, their crossing will somehow become less mysterious. The idea of linking a difficult problem of consciousness with a difficult problem of matter can be criticized on the same basis. But if you look closely, these two problems complement each other on a deeper and more defined level. One of the first philosophers who noticed this connection was Leibniz at the end of the 17th century, but Bertrand Russell formulated the exact modern version of the idea. Modern philosophers, including Chalmers and Strouson, reopened this connection. It is described as follows.

The difficult problem of matter requires finding non-structural properties, and consciousness is a phenomenon that can satisfy these requirements. Consciousness is full of quality properties, from redness to hunger and discomfort of hunger to the phenomenology of thoughts. Such experiences, or " qualia, " may have an internal structure, but there is something else in them besides the structure. We know something about the essence and inner properties of sensations, about what they are in themselves, and not just about how they work and how they relate to other properties.

For example, imagine a person who has never seen red objects and never heard of the existence of red. He knows nothing about how “redness” is associated with brain conditions, with physical objects like tomatoes or with a wavelength, or about how it is associated with other colors (for example, it looks like orange, but is very different from green ). And once a big red spot appeared in his hallucinations. Apparently, the person then finds out that there is redness, although he does not know anything about her connections with other things. The knowledge gained by him will be knowledge without relationships, knowledge of what redness is in itself.

From this it follows that consciousness in a primitively rudimentary form is the “iron” on which the software described by the physicists works. The physical world can be perceived as a structure of conscious sensations. Our own sensations realize the physical connections that make up our brain. Some simple, elementary forms of sensations realize the connections that make up the fundamental particles. Take an electron. The electron attracts, repels, and still somehow correlates with other entities in accordance with the fundamental physical equations. What constitutes his behavior can be thought of as a stream of tiny sensations of an electron. Electrons and other particles can be thought of as mental beings with physical abilities; like streams of sensations that are physically interconnected with other streams of sensations.

This idea may seem strange and even mystical, but it is born out of careful reflection on the limitations of science. Leibniz and Russell were scientific rationalists - which is proved by their immortal contributions to physics, logic and mathematics - but they were also deeply devoted to reality and the uniqueness of consciousness. They concluded that in order to pay tribute to both phenomena, it is necessary to radically change thinking.

And this is really a radical change. Philosophers and neuroscientists often conceive consciousness in the form of software, and the brain in the form of hardware. This assumption turns it upside down. If you look at what physics says about the brain, it will be, in fact, software - a purely set of relationships - to the lowest levels. And consciousness is actually more like iron, because its properties are qualitative rather than structural. Therefore, conscious experiences can just be what the structure of which is the physical structure.

If the difficult problem of matter is solved in this way, the difficult problem of consciousness disappears by itself. There are no more questions about how consciousness arises from matter that has no consciousness, since all matter is essentially conscious. There are no questions about the dependence of consciousness on matter, since it is matter that depends on consciousness — just as the relationship depends on the members entering into these relations, so the structure depends on the implementer, the software that runs on hardware.

One could argue that this is pure anthropomorphism — an unjustified reflection of human properties on natural phenomena. What makes us think that the physical structure requires some kind of internal implementers? Is it because our brain has intrinsic, conscious properties, and we are accustomed to thinking about nature in familiar terms? But this objection can be refuted. The idea that internal properties are necessary in order to distinguish real concrete things from abstract structures has nothing to do with consciousness. Moreover, the charge of anthropomorphism can be refuted by a contraposition of human exclusivity. If the brain is completely material, why should it differ from the rest of matter in its intrinsic properties?

This point of view, about the underlying physical reality of consciousness, is called differently, but one of the most appropriate names is " two-dimensional theory of consciousness " or "two-dimensional monism ." Monism contrasts with dualism , which says that consciousness and matter are basically completely different substances or types of things. Dualism is considered scientifically unfounded, since science does not demonstrate any evidence of the presence of non-physical forces affecting the brain.

Monism claims that all reality is made of the same substance. He is of different kinds. The most common monistic view is physicalism (also known as materialism ), which postulates that everything consists of a physical substance that has only one aspect described by physics. Today, this view is generally accepted among philosophers and scientists. According to physicalism, a complete and purely physical description of reality misses nothing. But according to the difficult problem of consciousness, any purely physical description of a conscious system, for example, of the brain, at first glance, still misses something. It cannot fully describe what it means to be such a system. It can be said to describe the objective, but not subjective aspects of consciousness: the work of the brain, but not our inner intelligent life.

Russell’s two-dimensional monism tries to fill this gap. He takes the point of view of the brain as a material system that behaves in accordance with the laws of physics.But he adds another internal aspect to matter, hidden from the external point of view of physics, which cannot be determined by any purely physical description. But, although this internal aspect defies physical theories, it is susceptible to our internal observation. Our consciousness constitutes this inner aspect of the brain, and this is our key to the inner aspect of other physical things. To paraphrase Arthur Schopenhauer’s laconic answer to Kant: we can be aware of a thing in ourselves because we are it.

Two-dimensional monism is moderate and radical. Moderate versions claim that the inner aspect of matter consists of the so-called. protoconsciousness or “neutral” properties: properties unknown to science, but different from consciousness. The nature of such neither conscious nor physical properties seems rather mysterious. Like the previously mentioned quantum theories of consciousness, moderate two-sided monism can be blamed for simply adding one puzzle to another, in the expectation that they will be mutually destroyed.

The most radical version of two-sided monism asserts that the inner aspect of reality consists directly of consciousness. This, of course, is not the same as subjective idealism asserts., saying that the physical world is nothing more than a structure that lives in human consciousness, and that the external world is in some sense an illusion. According to two-dimensional monism, the external world exists independently of human consciousness. But it would not exist independently of any type of consciousness, since all physical things are associated with some form of consciousness inherent in them, their own inner realization, or "iron."

As a solution to the difficult problem of consciousness, two-sided monism itself comes up against objections. The most common of these is that panpsychism follows., the idea of the universal animation of nature. Critics consider it unlikely to have a consciousness of fundamental particles. This idea really has to get used to. But let's look at alternatives. Dualism seems impossible from the point of view of science. Physicalism assumes that the objective, scientifically grounded aspect of reality is all reality, which means that the subjective aspect of consciousness is an illusion. Perhaps - but shouldn't we be more confident that we have a consciousness than that particles do not have it?

The second important objection is the so-called problem combination. How and why is the complex and united consciousness in our brain arising from the creation of a structure of particles with simple consciousness? This question looks suspiciously similar to the original problem. Together with other advocates of panpsychism, I argue that the problem of a combination is no longer as complicated as the original difficult problem. In some ways it is easier to understand how to move from one form of consciousness (a set of rational particles) to another (rational brain) than how to move from unreasonable matter to rational one. Many consider it inconclusive. Perhaps it is only a matter of time. Above the original difficult problem, in any form, philosophers thought for centuries. The combination problem is not so well known that it leaves hope for the appearance of a previously unnoticed solution.

The possibility that consciousness is a real and concrete aspect of reality, a fundamental “hardware” that allows the “software” of our physical theories to work, is a radical idea. It completely reverses our usual idea of reality, and such an idea is rather difficult to perceive. But it can solve two most difficult problems of science and philosophy at once.

Source: https://habr.com/ru/post/403253/

All Articles